Heaven and Earth interact perfectly, and the ten thousand things

communicate without obstacle. Those above and those below interact perfectly,

and their will becomes one.

— The commentary on the judgments of Hexagram Tai of the Book

of Changes

When men die, they enter into history.

When statues die, they enter into art.

This botany of death is what we call culture.

That’s because the society of statues is mortal.

One day, their faces of stone crumble and fall to earth.

…

But history has devoured everything.

An object dies when the living glance trained upon it disappears.

— Narrator from Statues Also Die (1953),

Directed by Alain Resnais, Chris Marker & Ghislain Cloquet

1.

The tour guide pushed the door open, and we entered. Initially, it

was pitch-dark; other senses were heightened, particularly the fear of disorientation

and claustrophobia. I saw nothing. But is darkness an image?

When our eyes started to adjust, an ethereal world unfolded. It was

overwhelming; the emergence of the images—from the murals and the

sculptures—created an all-encompassing perspective from above and around, as if

I was swallowed and shrunk, and now sat inside of the belly of the cave. As my

senses continued to adapt, the details of the images were revealed. In addition

to numerous mythological figures and religious symbols, the mural of this

particular cave tells an important karma story in Buddhist teaching titled “The

Five Hundred Bandits Reaching Enlightenment.” Through a long scroll progressing

from east to west, the story starts with the bandits, in the ancient Kingdom of

Kosala, South India, causing disturbances. Captured by the army, they were

punished by having their eyes dug out. The depiction shows the bandits being

stripped half naked with their hair loosened, body covered with wounds, blood

spattering the surroundings and the bandits wailing. In great suffering, the

bandits are sent out to the wildness of the forest. Then the narrative turns,

and the Buddha appears, blowing magical powder into their eyes to recover their

eyesight. The bandits converted into Buddhists, practiced, and meditated in the

mountains, and all achieved enlightenment in the end.

As I followed the story, what continued to interest me was not necessarily the

Buddhist teaching of Karma, but how I found my physical experience uncannily

corresponding to the part of the storyline where sight was lost and regained. I

couldn’t stop help wonder if my experience and understanding of the caves would

be entirely different if I hadn’t been in that disorienting darkness to

experience that temporary vision loss. Would I sense differently? Would I

perceive otherwise?

2.

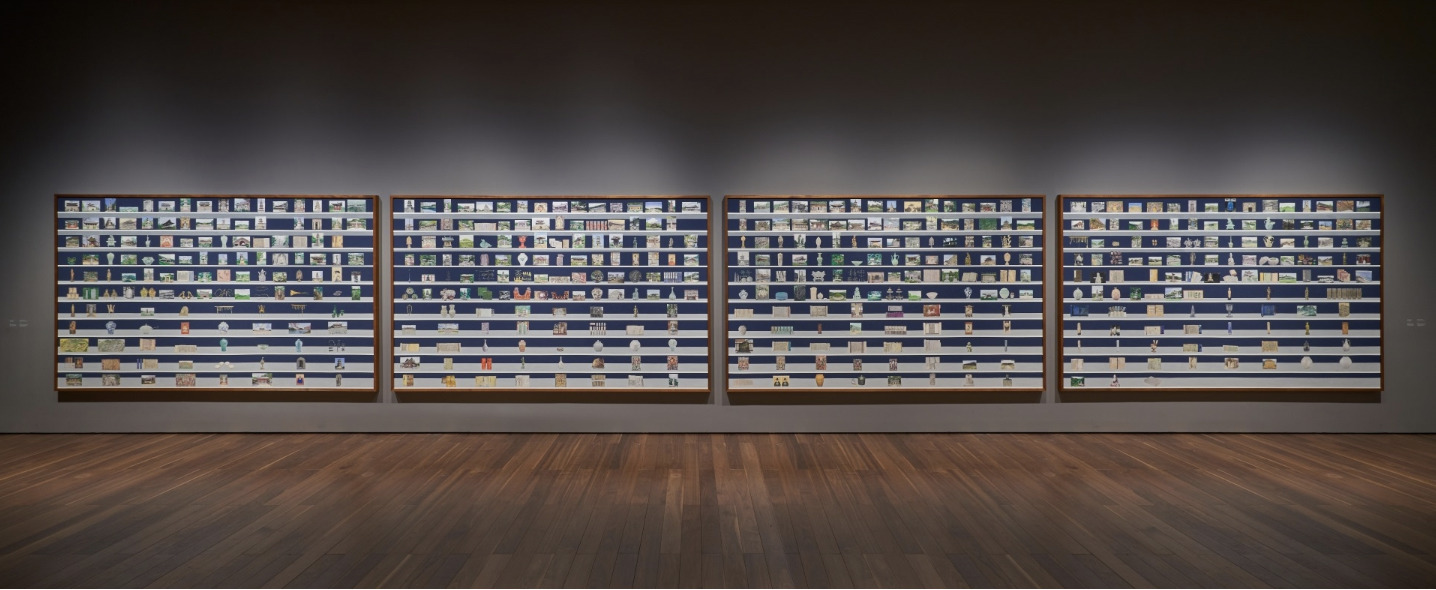

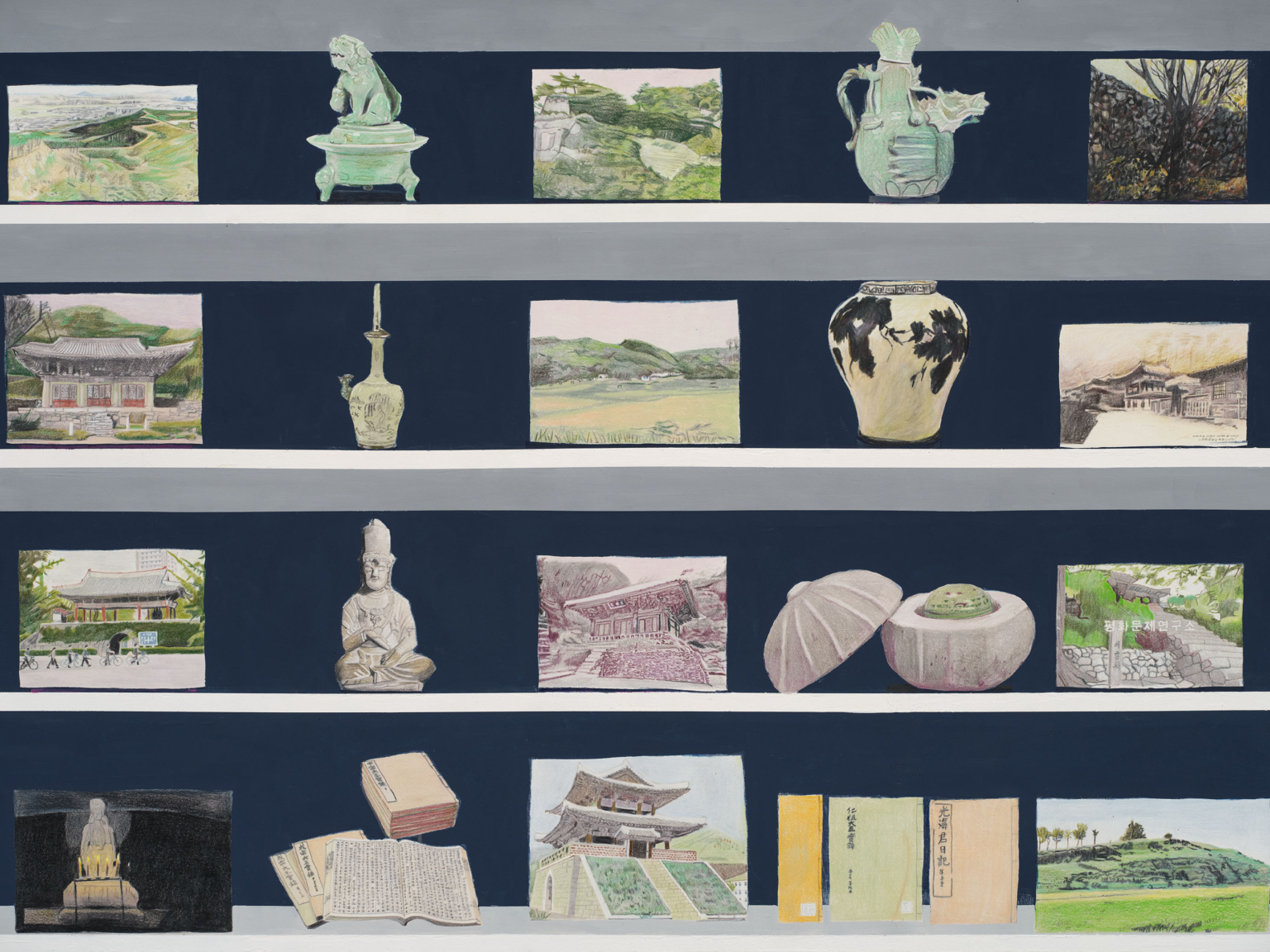

Gala Porras-Kim’s work had been on my mind since the beginning of

this trip. At the time, she just completed the triptych The

Weight of a Patina of Time (2023) for the 2023 Korean Artist

Prize nomination, which compromises three large-scale drawings that provide

imagined and realistic viewpoints on one of the dolmens from the Gochang Dolmen

Site, located in the current Gochang of the South Korea territory. To the

casual eye, the first drawing seems to be a simple pitch-black image, devoid of

any content; only the reflective and metallic surface created by layers of

pencil graphite strokes give away its materiality. The second drawing is a

photo-realistic but black-and-white depiction of the dolmen sitting in the

landscape, where trees, bushes and wildflowers hug it. On the lower right

corner of the composition, a small plate shows the number 2408 along with a

Korean phrase, partially covered by weeds. The last drawing, and the only

multicolor one of the three, pulls the viewer into an eerie realm, where

nothing is fully formed, and mottled and variegated patterns oscillate between

an abstract drawing and a rendering of an organic microscopic world.

The intention here, according to the artist, is to speculate and postulate

three different perspectives on the same dolmen from the Gochang Dolmen Site.

Found in many parts of the world, dolmens are ancient megalithic structures

consisting of two or more upright stones supporting a horizontal stone slab,

believed to have been used as tombs or burial chambers during the Neolithic and

Bronze Ages. The site of Gochang comprises over 440 dolmens that are believed

to have been constructed by the people of the Mumun Pottery Period (lasted from

around 1500 BCE to 300 BCE) and are scattered across an area of around 100

square kilometers. Together with sites Hwasun and Ganghwa, it was designated as

a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2000.

In Porras-Kim’s work, which took two weeks, two months and four months

respectively to complete, the black drawing suggests the dead person’s point of

view, the one who might have been buried under the ground of this particular

dolmen; the drawing of color pencil and wax proposes a perspective of nature,

wherein the seemingly abstract color patterns are supposedly to be viewed from

of the insects, animals, and the moss and lichen attached to the stone, growing

over the millennia; and the realistic depiction of the dolmen in the landscape

represents the human’s perception. The partially covered plate with the number

is in fact the UNESCO label to index this particular dolmen number 2408 in the

park.

Here, photorealism and abstraction are not in opposition. If described in

conventional art history visual analysis terms, the color drawing and the black

drawing are both formally abstract. However, in Porras-Kim’s work, these are

“realistic” views of “beings” whose experience is intangible to us. What seems

nonrepresentational attempts to fill in information that is not always

accessible or comprehensible. Displayed side by side, the three drawings show

three realities that entangle various spatial, temporal and experiential

dimensions. They may be imaginary but are hardly fictitious, and only the

limits of our own perception prevent us from substantiating the unperceived as

true.

Porras-Kim has previously produced similar works to the black drawing for her

other series that investigate archeology objects and sites, including Two

plain stellas in the looter pit at the top of the Sun Pyramid at Teotihuacan (2019),

which recreates the darkness inside a pyramid in the ancient Mesoamerican city,

and Mastaba scene (2022), which portrays the interior of an

impenetrable 4,500-year-old Egyptian sarcophagus from the British Museum’s

collection. Except for their different titles and dimensions, and varied pencil

marks seen only if one looks closely, these graphite on paper works almost look

identical. Humorously, Porras-Kim has invited us to imagine, along with her,

what kind of scene a dead person (or us ourselves if we were dead) would be

seeing lying under the dolmen’s burial ground, inside of the pyramid or the

sarcophagus. Moreover, the darkness comes to delineate the limits and

constrains of human perception and make visible the blind spots that occlude

our vision when recording history and constructing knowledge. These three black

drawings become the anchors of the exhibition at MMCA that connect different

bodies of Porras-Kim’s work. They not only pay respect to and acknowledge the

agency and potential of the ancient spirits but also serve as a spiritual

landscape or portals that take our imaginations through the porosity and

multiplicity of other experiences and realities.

In some of her earlier work, Porras-Kim has focused on employing artistic

gesture as a means to bridge the visual and non-visual and translate seeing to

other forms of perceptive senses, particularly knowledges that are formed,

recorded, and circulated in ways that are outside of the classical Western

framework and European modernity. For the project Whistling and

Language Transfiguration (2012), Porras-Kim made a vinyl record

documenting her effort in learning Zapotec, an endangered tonal language spoken

by the indigenous people of Zapotec in Mexico. Originated in Oaxaca, Zapotec

was transmitted until recently entirely through an oral tradition, without

written records. An exceptionally tonal language, the content of the words is

partly contained within the intonation of speech, to the degree that meaning

can be communicated through tones alone and words can be emulated by whistling.

While Zapotec is not the only whistled language in the world, it is unique in

that it evolved as a strategy of resistance against Spanish colonizers. By

communicating through whistling, the indigenous population disguised their

conversations as musical diversions. In addition to recording her own whistling

of the language, Porras-Kim also transcribed the sounds into musical notes.

Similarly, in Muscle Memory (2017), a video work that documents the silhouette

of a dancer, who tries to perform traditional Korean chorography without music

or any rhythmic or exterior cues.

The muscle memory formed by the repetitive

movement of the body becomes the vessel to preserve and archive knowledge.

Performed each time by different dancer who acts and moves with different body

shape, anatomy, and interpretation of the choreography, the particular

knowledge is continuously evolved and adapted. Resonantly, in many ways,

learning a language through oral tradition is also a way of creating individual

muscle memories of facial movements and the tactile sense of the tongue and

lips twisting, folding, touching the teeth and collecting saliva.

Together, Whistling and Language Transfiguration and

Muscle Memory poetically tease out the dynamic tension between collective

history and individual experiences imbedded in immaterial records.

3.

Porras-Kim’s practice consistently challenges the human-centric

experience and the Anthropocene position of Western epistemology and its

colonial projects. In order to do so, she actively engages non-human objects

and other unconventional entities such as human remains, dusts, bacteria, and

fungi, “ordering” things to ravel and unravel what Michel Foucault calls “the

relations (of continuity or discontinuity) between nature and culture.1”

Porras-Kim’s practice has a strong anthropological impulse, and echoes with

what Descola’s says that “Culture or cultures, as the system of mediation with

Nature invented by humanity… includes technical ability, language, symbolic

activity and the capacity to assemble in collectivities that are partly free

from biological legacies.2” Porras-Kim’s collaboration with nature

is never intended to simply romanticize the non-human consciousness or to

function as a portal to escape humanly reality, but is supported by a deep

understanding of nature as contingent on our anthropological lens: it is only

accessible to us through the devices of cultural coding which objectify it:

systems of classification, scientific paradigms, technical mediations,

aesthetic forms, and religious believes. The artistic manipulations and

representations of the body, the object and the environment thus are not an end

in itself, but rather a means of accessing the intelligibility of the various

structure which organize relations between humans and non-humans. Porras-Kim’s

work not only serves as a critique of the opposition between nature and culture

imposed by Western epistemology, but more crucially as a dynamic reworking of

the conceptual tools employed for dealing with the relationships between

natural objects and social beings.

The “natural elements” that Porras-Kim “invites” to collaborate with, such as

microbiome, rainwater, or ambient humidity in the environment, have of course

always been there. Those who are often neglected have long predated, and will

outlive us – myriad fungi, bacteria, and other microorganisms. They are not

guests but rather “invisible” hosts to the human eye. In her ongoing

series Out of an instance of expiration comes a perennial showing (2022-ongoing),

Porras-Kim grows mold spores collected from the British Museum’s storage and

encourages them to propagate on an agar-soaked muslin cloth, encased within an

acrylic vitrine. Over the course of the exhibition, hairy, fluffy, grey-brown-green

mold growths gradually develop and turn the then blank fabric into a rich

microscopic world as well as a living painting. A source of concern for

conservators at museums, as Porras-Kim notes, “the mold spores ate objects in

the collection” over time if not managed properly. Consider an interesting

point made by geologist and paleontologist Jan Zalasiewicz, who speculates

future extraterrestrial excavators may not think human as the dominant rulers

of the Earth worthy of restoring and worshipping, as we have enshrined giant

dinosaur skeletons in museum displays as the foreground of the Jurassic

landscape. Instead, the yet-to-be-born or arrived explorers may be more

concerned with the myriad tiny microbiomes and microorganisms—who have

maintained a stable, functional and complex ecosystem in fact required for our

survival3. Porras-Kim’s approach echoes Zalasiewicz’s proposition,

seeking to acknowledge lives that are dismissed, omitted or trivialized in

order to construct a seemingly factual yet often biased and ignorant idea of a

history past. “By regrowing them in the space,” the artist continues, “we can

see these objects reconstituting into a new form” just as when the top predator

dinosaurs vanished 200 million years ago or if humans disappear in the future,

the world will present new colors and compositions in its living tapestry.

But Zalasiewicz is not ready to let human vanish yet. He would still like to

hope for awe and reverence from our future excavators, and that in their

investigation of the Earth’s history they would still find fascination in our

own mortal remains. There are no shortage of human remains in today’s museum

collections, including those two unidentified human bodies from the Gwangju

National Museum in South Korea, who have become collaborators with Porras-Kim.

Originating from a centuries-old shipwreck, these remains have been kept at the

museum as objects of study, identified only by the codename Sinchangdong43,

their humanity stripped away. Intrigued and troubled by this institutional

practice, Porras-Kim seeks restitution of these artifacts’ rights to that of

the bodies of deceased people. She reminds us that, in many cultures and

cosmologies, “it should ultimately be the prerogative of the person to

determine what their body becomes after death. Museums have the capacity to

recognize that humanity at any time, and should do so.4” Using

“necromancy”, a form of divination through pattern-making to communicate with

the spirit, Porras-Kim asked the deceased where they would prefer their remains

to be buried instead of the museum. The necromancy is achieved through paper

marbling techniques— submerging paper in a pan of water, then dropping ink onto

the submerged paper to form striations and swirls. The resulting image in A

terminal escape from the place that binds us (2022) shows what

the artist calls a “potential landscape” that charts topographic terrains.

Though the image remains abstract and show no definitive answer with regards to

the deceased’s desires, Porras-Kim is able to construct a ritual passage to

honor their afterlives.

Perhaps the abstract image is a different kind of wayfinding tool, not

comprehensible to our experiential dimension but more straightforward to the

consciousness in another scale or realm. Similar to the color drawing

from The Weight of a Patina of Time of nature’s

perspective on the dolmen, A Terminal Escape from the Place That

Binds Us might show us the view from a microcosm where tiny

organisms and life forms interact and thrive in ways that are unimaginable and

alien to human experiences. Even under the most controlled conservation

conditions, organic remains continue to decompose in museums or other storage

facilities, whether through insects, bacteria or fungi growth or by the gradual

chemical effects of degradation and oxidation. Perhaps, the deceased have

reincorporated their spirits back into nature, diffused from the museum, and

are now resting and evolving with the lakes, rocks, soil, and many strata and

layers of organic and inorganic, living and non-living worlds.

4.

The conceptual tools Porras-Kim employs to renegotiate the binary

opposition between nature and culture imposed by the Western epistemology often

turn on the creative reframing of practices that modern science and technology

have hastily denounced as superstition, irrationality, or primitiveness often

without fully understanding (or at times deliberately refusing to understand)

their multiple and varied cosmologies. In addition to facilitating

communications with the dead, Porras-Kim summons other “spirits” such as

exhalations, moistures, soil, and dust as what the artist posits to be

“physically and figuratively trapped within institutions”5 and

creates “conducive environments” to let them out, including planning and

organizes rituals and ceremonies, with the cooperation from the institution’s

curators and conservators, to restore museum objects’ spiritual life and awaken

their suppressed capacities for magic and power.

In Forecasting Signal (2021-ongoing), Porras-Kim

set up an oracle which conjures an artwork-to-come: a dehumidifier extracts

ambient water from the exhibiting space; as the water accumulates and

condenses, it filters through a hanging burlap sheet saturated with graphite

powder extended from the ceiling and drops onto a blank canvas panel place on

the floor, where an artwork-as-prophecy is created over the course of the

exhibition. Echoing those seen in Eastern Asian ink paintings, the at times

spontaneous and fluid, at others chaotic and energetic textual depth and ink

layering divulge a prophecy of the particular site, be it a conventional

white-cube gallery or a historical- monastery-turned-museum. In Precipitation

for an arid landscape (2021), the artist looks into the troubled

history of the excavation of the Chichén Itzá cenote, a sacred Mayan sinkhole

located in the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico, a geologic landscape dense with

caves. Believed by the Mayans to portals between the secular realm and the

netherworld, and temporary deswellings of Chaac, the Mayan god of rain and thunder,

these openings became burial sites for human bodies and funerary objects,

placed according to ritual. to ensure that the rain god might access them. As

part of archeological excavations during the early 20th Century,

the sinkholes were dredged and the sacrificial artifacts and remains were

removed and ultimately became the holdings of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology

and Ethnology collection at Harvard University. For the sculptural part of this

series of work, Porras-Kim mixes copal, a meltable tree resin used to backfill

a void from which an artifact has been removed during archeological

excavations, with dust collected from the storage area where the artifacts are

stored at the Peabody Museum to make a rectilinear slab or a cube sometimes.

This object, placed on a platform or pedestal, is meant to be splashed by

collected rainwater during a daily ceremonial procedure, of which the format

and participants are interpreted and determined by the exhibiting institution.

In doing so, the sculpture assumes a new life that facilitates the reunion of

the sacrificial artifacts and remains with the Mayan rain god.

5.

Geochemist Vladimir Vernadsky describes life itself as a

continuous process of happening. Vernadsky speaks in a profound geological

spacetime, which Porras-Kim’s practice echoes. In her works, natural time,

experiential time, death time, spiritual time, decay time, museum time and

historical time intertwine and collide in an ever evolving and becoming

artistic configuration. On the one hand, though a conceptual artist at heart,

Porras-Kim is never a conventional conceptualist. Ideas that come like a flash

of insight or those that are mere conceptual gestures are not the point. On the

other hand, highly research-based, Porras-Kim’s practice is also not a mere

visualization of her research topics. Instead, process and materials are

crucial, and the politics of aesthetics are imbedded in the subjects, mediums,

surrounding infrastructures, participants and audiences; together constituting

the complexity and depth of her work.

The choice of drawing as a core medium with pencil and graphite, for example,

is deliberate, as according to the artist, these are the most accessible and

versatile artistic materials in everyday life. The resulting work, as intended

by the artist, therefore, stands as sketch, study, and rebellion against

“traditional” oil painting in particular, which can potentially “liberating

them from the pedestal and confines of a capital “A” in considering what

constitute an artwork.6” The accessibility and fluency of drawing

with paper and pencil becomes a tool and an exercise for Porras-Kim to learn from

her subjects. Mostly made from photographic documentation and often similar to

the original scale of what’s being depicted, the drawing process not only

allows Porras-Kim to observe and study every tiny and distinctive detail in the

cracks and patterns of her subject but also to reach and test certain limits,

whether it is the size of the objects in relation to her own body, or the

physical endurance in the painstakingly long hours and repetitive movements

required. In this way, Porras-Kim’s drawing process becomes performative: the

drawing process becomes a ritual—not unsimilar to the rainwater splashing

in Precipitation for an arid landscape—that goes beyond

the mere representations of the subject maters but actively reproduce and

reconstitute new social relationships and cultural realities for them.

6.

Unsurprisingly, given her insightful and witty engagement with not

only many historical artifacts but also various aspect of museum and

institution administration, many of the productive discussions around

Porras-Kim’s work have focused on the complex issues around repatriation and

its relationship with museology, cultural heritage, and policymaking in an era

reckoning with past and ongoing colonialism. The 1953 French cinematic

classic Statues Also Die first brought to light

these issues in a widely circulated format and remains one of the most

important and extensively quoted work. The directors Alain Resnais, Chris

Marker and Ghislain Cloquets searingly criticized the damaging impact of

colonialism through the lens of European museum collections of ritual and

spiritual artefacts from Africa. Because of its critical stance, the film was

censored by the French National Center for Cinematography and was not allowed

to be shown in French cinemas until 1964. Porras-Kim shares many sensibilities

with the film, particularly the acknowledgement of the multiple lives of

historical objects as ritual objects and spiritual objects besides, originally,

or perhaps more importantly. It is clear that much of museum practice today

reflects and indeed continues a troubled legacy, an outdated structure that

belongs to the specific technology of the colonial time and epistemology

hardwired into Western institutions.

For many, repatriation is understood as geographical meaning of physically

returning the artifacts to their counties or places of origin. For Porras-Kim,

this is far from being true or enough. There is much work to be done beyond

just geographical borders and nation state politics to continue, for example,

the restoration of cultural identity, the reframing of legal and ethical

frameworks, the reconciliation of historical injustices, colonial exploitation,

and cultural imperialism, and the rewriting of history. By creating a

conceptual structure and focusing on process—through its performative

repetition and duration— Porras-Kim’s practice intends to shape cultural norms,

identities, and social structures surrounding these crucial issues. Her

practice integrates itself into the everyday, and the agency to cross

boundaries, to bridge life and death, and to open up multiplicity.

I am not surprised that as I wander through the thousand-year-old Mogao

Grottoes in the Gobi Desert, thousands of miles from home, I have Porras-Kim’s

work in mind.

1 Michel Foucault, The Order of Things (London:

Routledge, 1975), 412.

2 Philippe Descola, The Ecology of Others, trans. Geneviève

Godbout and Benjamin P. Luley, (Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2013), 35.

3 Jan Zalasiewicz, The Earth After Us: What Legacy will

humans leave in the rocks? (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008),

191-218.

4 Defne Ayas, “Gala Porras-Kim, A terminal escape from the place

that binds us,” 13th Gwangju Biennale,

https://13thgwangjubiennale.org/artists/gala-porras-kim/.

5 A terminal escape from the place that binds

us, Commonwealth and Council, November 6 – December 18, 2021,

https://commonwealthandcouncil.com/exhibitions/a-terminal-escape-from-the-place-that-binds-us/press.

6 Gala Porras-Kim, Author’s conversation over zoom, September

2023.