I.

“There

can be no freedom without madness to sever the rope.”

No aphorism better represents the artistic world of Atta Kim than this line

from Nikos Kazantzakis’s novel Zorba the Greek. The

essence of Atta Kim’s practice—seeking to dismantle religious taboos, social

conventions, the limits of the body, and the boundary between the sacred and

the profane—ultimately converges on the question of how human beings can

acquire freedom.

He

pays close attention to how humans, originally born free, undergo processes of

socialization as they live their lives, and how they gradually adapt to society

through collective living. What is paradoxical, however, is the manner in which

he expresses this concern. In conclusion, his work focuses on the force of

resistance positioned at the antipode of conformity. He appears to possess a

deep awareness that the freedom humans are compelled to relinquish as they

assimilate into society, and the social oppression and control that intensify

in proportion to that relinquishment, together constitute the very shackles

that bind human beings.

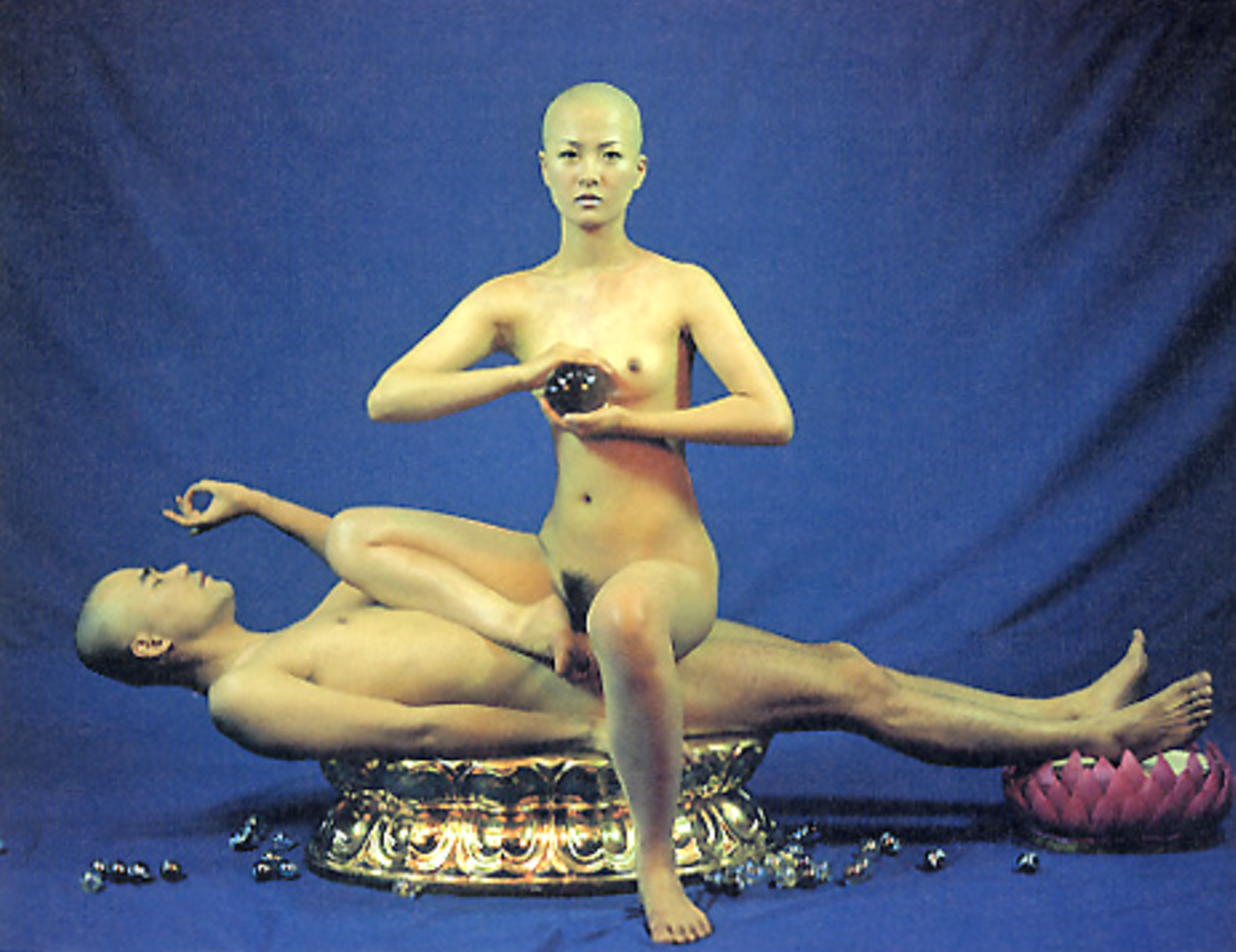

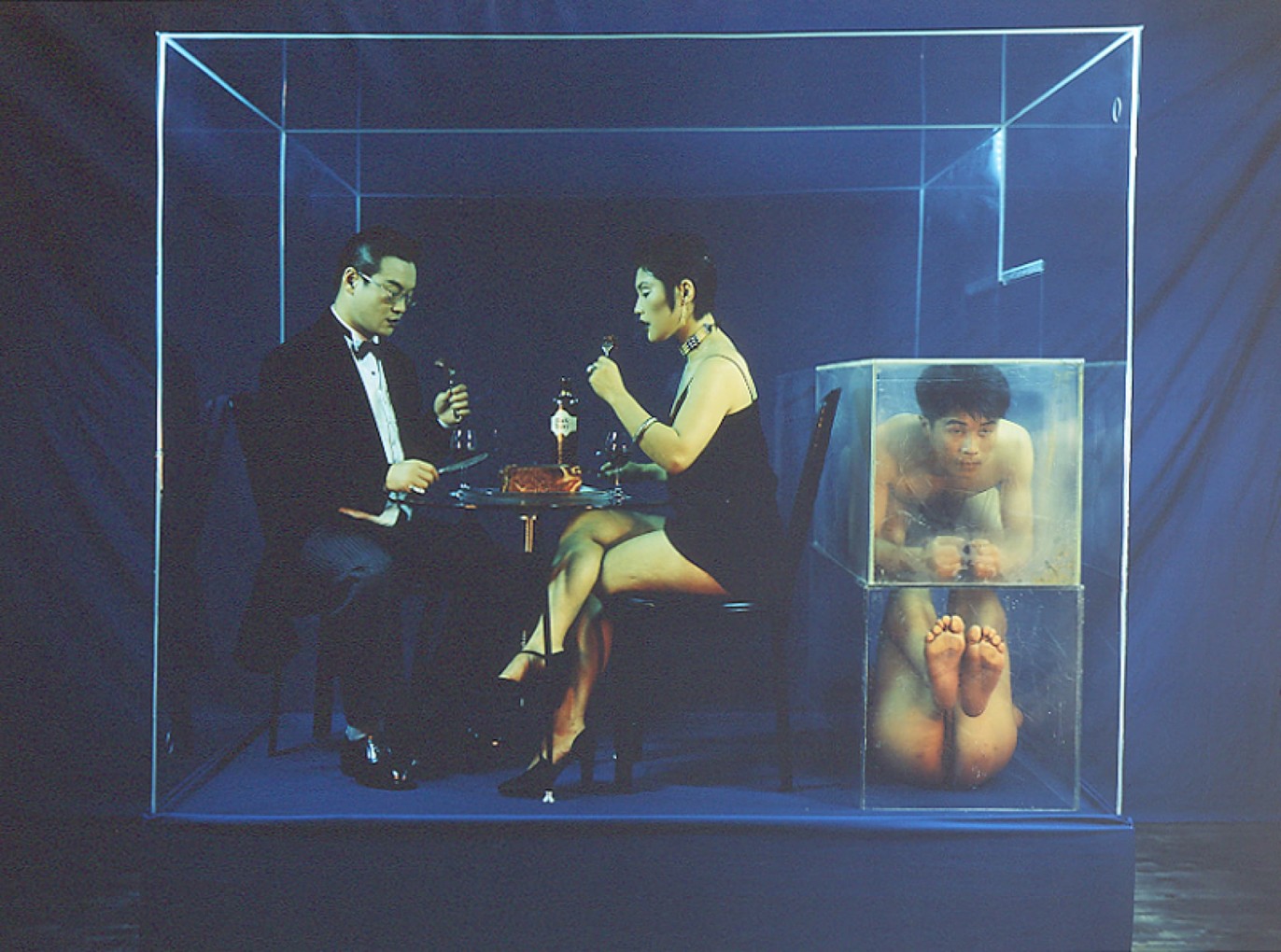

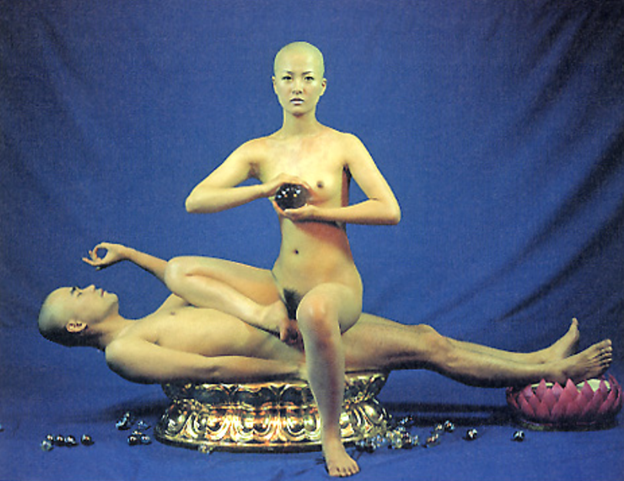

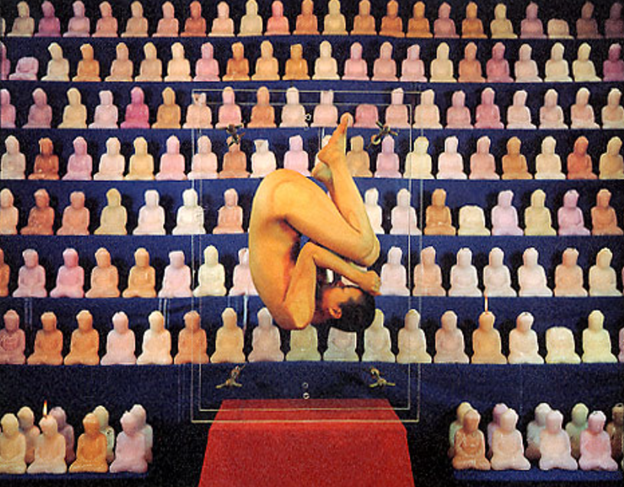

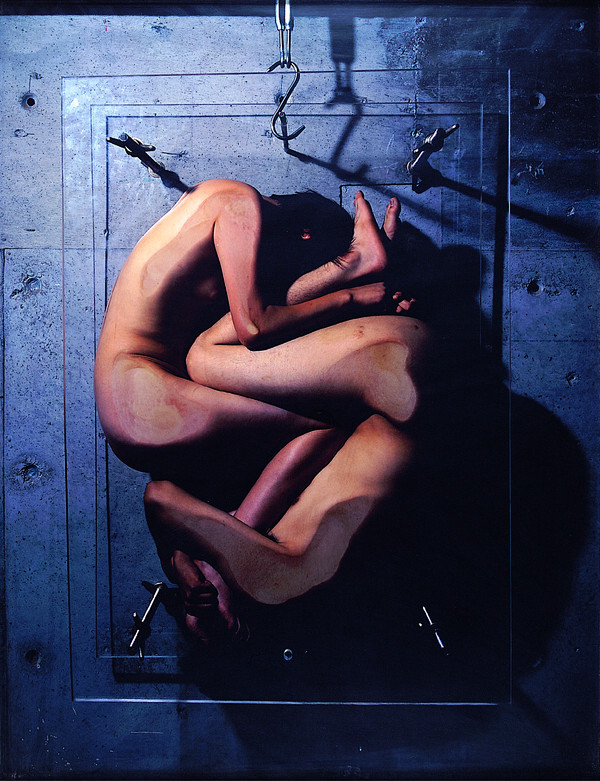

Might

not the acrylic box that he frequently employs be the symbol of such

oppression? This interpretation becomes self-evident when one notes that

'Museum Project'(1995–present), represented by acrylic boxes, appears after

'Deconstruction'(1992–1995), in which nude human bodies were laid out in

nature. If 'Deconstruction' can be understood as an attempt to return humans to

the bosom of nature, then 'Museum Project' is a kind of reversible landscape

that reduces human beings to a symbolic system of oppression.

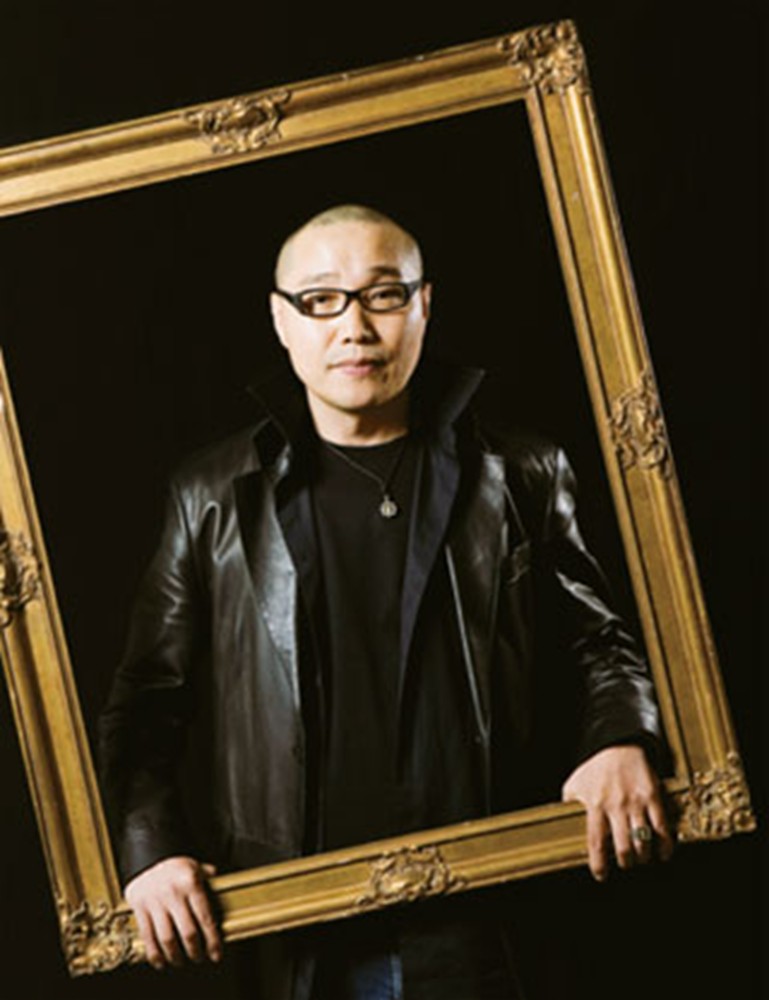

This

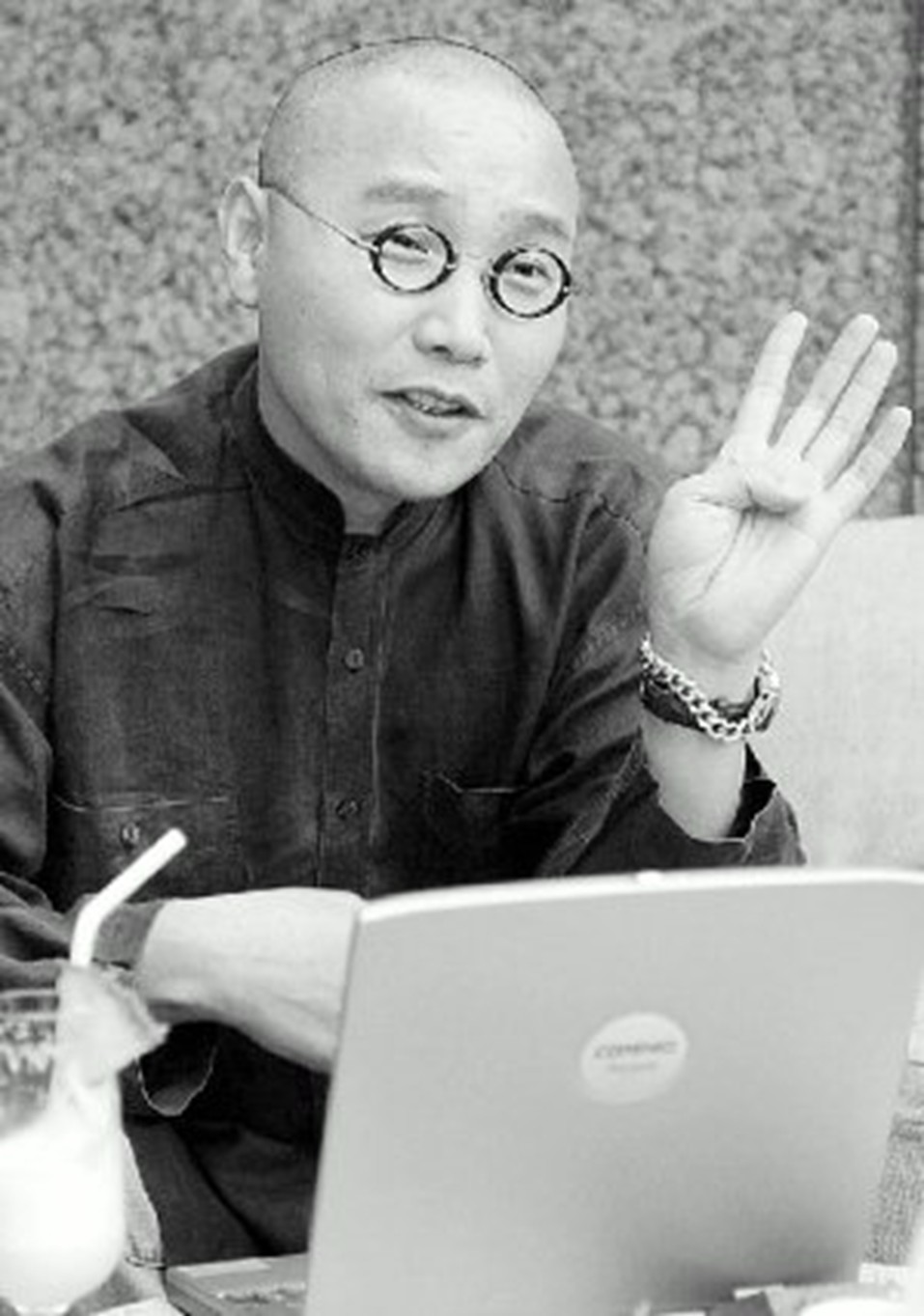

essay was written to illuminate the artistic world of Atta Kim, who has

consistently pursued work centered on humanity and nature since the mid-1980s.

When looking back over his life, what stands out most clearly is his personal

history. In particular, how someone who majored in mechanical engineering

during his university years came to enter the art world, and how he became

captivated by photography, remains one of my central interests. Many of my

questions were resolved through a long-standing acquaintance with him, and

ultimately became the motivation for writing this text. In addition, his

extraordinary life trajectory, his passion for art, and the distinctive

charisma evident throughout his working process all attest to the innate

artistic endowment found in an artist of considerable magnitude.

II.

As

is often the case with artists of exceptional talent, Atta Kim, too, has lived

a life entangled with spiritual wandering and exile. These factors form a

substratum within his work. His recollections—such as being more absorbed in

photography than in his major of mechanical engineering during his university

years, or frequently lingering around philosophy lecture halls—suggest that

even at that time, the seed of an artistic passion had already begun to sprout

within him.

During

his university years, while living a life detached from his major, Atta Kim

developed a deep interest in literature, philosophy, psychology, art,

photography, and travel, thereby cultivating a broad foundation in the

humanities. Having entered university slightly later than his peers, he also

had the opportunity, during the period from the late 1970s to the early 1980s,

to travel extensively throughout Korea and encounter a wide variety of people

and objects. The experiences of spiritual wandering and physical travel during

this period—centered on photography and poetry—became the single most

significant factor in maturing his artistic world.

Atta

Kim’s relentless interest in human beings and his artistic efforts to grasp the

essence of humanity are embedded throughout works that take humans as their

subject. For him, humanity is an inexhaustible source of inspiration and a

central theme. What is a human being? What is the true nature of a being that

possesses the Janus-faced dualities of good and evil, darkness and light,

strength and weakness, nobility and baseness, truth and falsehood? What is the

true countenance of a being who, endowed with seven instincts—joy, anger,

sorrow, pleasure, love, hatred, and desire—repeatedly walks a perilous

tightrope between reason and emotion? Atta Kim sought to pose this difficult

question through his photographic practice.

The

series 'Mental Patients'(1985–1986) is the outcome of an intensive inquiry into

human essence. Over approximately one year, at a psychiatric hospital located

in Gyeongsangnam-do, he observed and photographed more than 350 psychiatric

patients in a documentary manner. These photographs possess value not only as

art photography but also as a form of sociological or even clinical material.

Through close interaction with the patients, Atta Kim began to question the

criteria used to divide normality and abnormality. His interest in human

behavior—where reason and madness coexist, and where everyday life borders on

deviation—was realized through observation of psychiatric patients.

The

scenes of the psychiatric ward seen through the camera’s viewfinder are nothing

other than institutional products created by rational subjects who take

pleasure in endlessly fragmenting and demarcating the world. To borrow Michel

Foucault’s words, is not the prison (the psychiatric hospital) precisely the

product of the symbiotic relationship between knowledge and power that unfolds

around madness and confinement?

Atta Kim encountered countless individuals

labeled as mad within the psychiatric hospital. His close observation of

normality and abnormality, and of the everyday and the deviant, later led to

attempts in his work to dismantle the boundary between self and other. More

recently, by renaming himself Atta (我他), he further solidified his intention to dismantle fixed human

preconceptions regarding objects and phenomena by collapsing the opposition

between self and other.

III.

The

existential awareness that the other exists because I exist runs through all of

Atta Kim’s work as its fundamental spirit. The seemingly self-evident

truth—that the existence of the other is meaningful because I exist here and

now (hic et nunc)—appears as an unshakable principle. Frequently declaring, “I

am an existentialist,” he understands the here and now as a measure of

world-perception composed of warp and weft, constantly moving through time and

space.

To

borrow the words of Karl Jaspers, he is someone who opens his heart to others

encountered along the path of life. He does not acknowledge dogmatic truths and

is always ready to learn with an open mind. His spiritual wandering is marked

by a confirmation of the absence of ultimate truth. Again citing Jaspers, “The

world is a paradox, and human cognition is a collection of fragments.”

Atta

Kim’s work is structured through dialectical tension achieved by negation. The

negation of the existence of things, and the negation of the presence of states

of affairs, form the foundation of his practice. He photographs humans yet

negates humanity, and through this negation moves on to other things. Yet those

things are negated again, and that negation advances toward a third other. It

is akin to slicing an onion again and again: the onion before one’s eyes

disappears, yet the concept of the onion remains.

In

this sense, the fact that he employs photography—a medium commonly known as the

most accurate means of representing objects—is itself a paradox. However, he

does not believe that “photography speaks the truth or faithfully represents

truth” (Atta Kim, work notes). Rather, he believes that photography “can be

more honest about what is opposite to truth disguised as truth.” He

photographed psychiatric patients over a long period. Was that truth? Or was it

the photographing of a preconceived notion? Was it not merely what Roland

Barthes calls studium?

This

methodological skepticism leads him back to his father, from his father to

holders of intangible cultural heritage, and from them to grass, trees, stones,

and other elements on the ground.

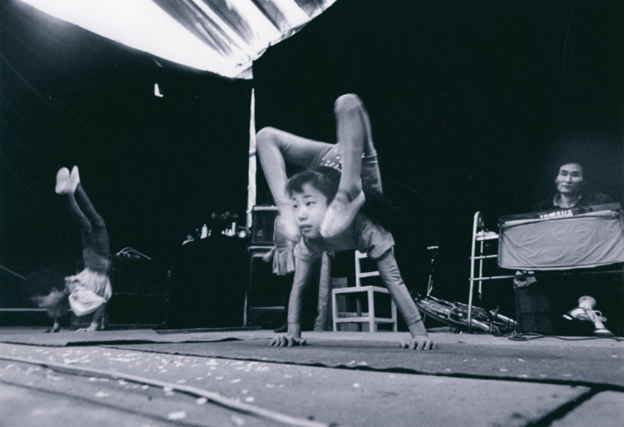

His

passion for purity often entails infinite endurance. The interest in the other

that developed as an extension of his spiritual wandering during his university

years bore fruit in the series 'Mental Patients'(1985–1986) and

'Father'(1986–1990), followed by the series 'Human Cultural Assets'(1989–1990).

Over the course of approximately two years, he photographed more than 150

individuals designated as holders of Important Intangible Cultural Properties,

including Ha Bo-gyeong, the bearer of the Miryang Baekjung Nori; Lee Dong-an,

master of mask dance; Monk Manbong, a dancheong artisan; Kim Dae-rye,

practitioner of the Jindo Ssikkim-gut; Kim Geum-hwa, master shaman of the West

Coast Baeyeonsingut; and Kim Seok-chul, bearer of the East Coast Byeolsingut for

abundant fishing.

Atta

Kim recalls that the period during which he met these human cultural assets was

“a time of intense learning.” Seen across his entire body of work, the 'Human

Cultural Assets' series marks the conclusion of his conceptually driven phase.

Moving beyond the cultural taste evident in 'Mental Patients' (in the sense of

Barthes’s studium), the concerns with ethnic identity glimpsed in 'Father' are

more densely assimilated in 'Human Cultural Assets'.

Although

these works, which present frontal portraits of their subjects, appear too

ordinary to claim novelty in terms of photographic aesthetics, they

nevertheless occupy a significant place in his oeuvre. This is because the

diverse experiments that unfold in earnest after 'Deconstruction'(1992–1995)

are grounded in the understanding of the world and humanity that he acquired

during this period.

In fact, the five to six years spanning from 'Mental

Patients' to 'Human Cultural Assets' were a pure period of open-hearted

practice, extending from his earlier apprenticeship. During this time, with the

open sensibility characteristic of a spiritual wanderer, he was able to receive

things without prejudice and broaden his vision through the negation of

ultimate truth.

IV.

Between

'Human Cultural Assets' and 'Deconstruction' lies the series

'Being-in-the-World'(1990–1992). This marks a period in which his focus shifts

from humans to things. Following a severe spiritual ordeal around the time of

'Father', he turned his gaze from humanity to nature, attempting communion with

it. He carried out this work during the hours of 3 to 5 a.m., the so-called

Tiger Hour (寅時). This time is known as

the hour when the Buddha attained enlightenment, and is considered the clearest

and most pristine moment of the day, when a new day is born.

Relying

solely on faint starlight and moonlight, he maintained exposure times of one to

two hours. Through this process, he gained profound experiences of time and

space: that time and space are composed of countless fragments of the here and

now; that objects constantly don new appearances in between; that through this,

objects approach us with renewed sensations; and that the world cannot be

manipulated but remains open toward the future.

The

black-and-white photographs comprising 'Being-in-the-World' depict pebbles,

tree roots, and grass faintly revealing themselves in the dim light of dawn. In

Heidegger’s fundamental ontology— from which the title 'Being-in-the-World' is

drawn—Dasein is not an isolated being but one that interacts with other beings

in the world, existing as a possibility endowed with intentionality.

Atta

Kim’s transition from understanding humans to understanding things, and from

there toward the integration of humanity and nature, is, as previously

mentioned, a confirmation of dialectical negation. In other words,

understanding the world inevitably prepared the passage toward

'Deconstruction'—that is, toward an open horizon of the future.

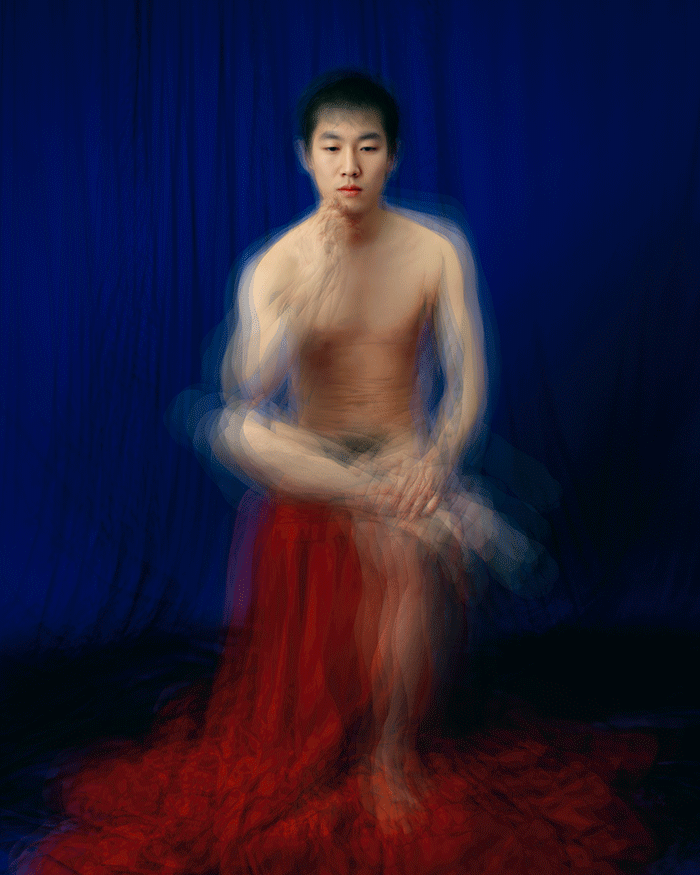

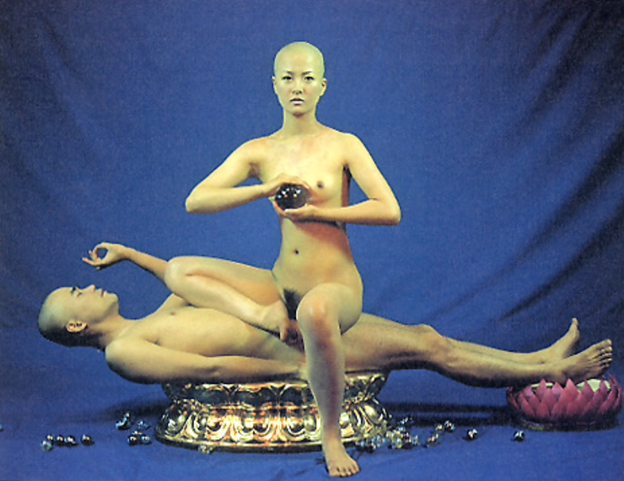

'Deconstruction'(1992–1995)

presents a horizon in which nature and humanity are integrated. In his words,

“Deconstruction is the act of sowing humans—beings composed of conceptual

sediment—into the fields of nature.” Within his entire body of work, the significance

of 'Deconstruction' lies in the fact that this is where the technique of

defamiliarization first appears. The shock of this series stems above all from

the nude bodies strewn across nature.

Naked

men and women lying along winding asphalt roads descending slopes confront

viewers with a jarring image due to its sheer unreality. These scenes, staged

with roads blocked at both ends, constitute performances. In fields, barren

mountains, wetlands, abandoned docks littered with disused ships—each setting

hosts a different staging of 'Deconstruction', and behind these photographic

records lie countless anecdotes.

At

this point, Atta Kim reveals his artistic capacity as a group leader. He

transforms into a director who commands staff and male and female participants

involved in the shoots.

“Deconstruction

is true freedom,” he says. He also asserts that “progress is destroyed by

progress.” In saying this, he appears to have modern technological civilization

in mind. “Progress without reflection will ultimately be destroyed by progress

itself, and my work begins from reflection that restrains the centrifugal force

of such progress,” he adds. Thus, he views human liberation from

technology-centered progress as originating in the moment when true freedom is

attained.

While

this perspective may appear somewhat naïve, the bold strategy of juxtaposing

naked human groups against nature becomes the foundation for 'Museum Project'

and 'Nirvana Series'.