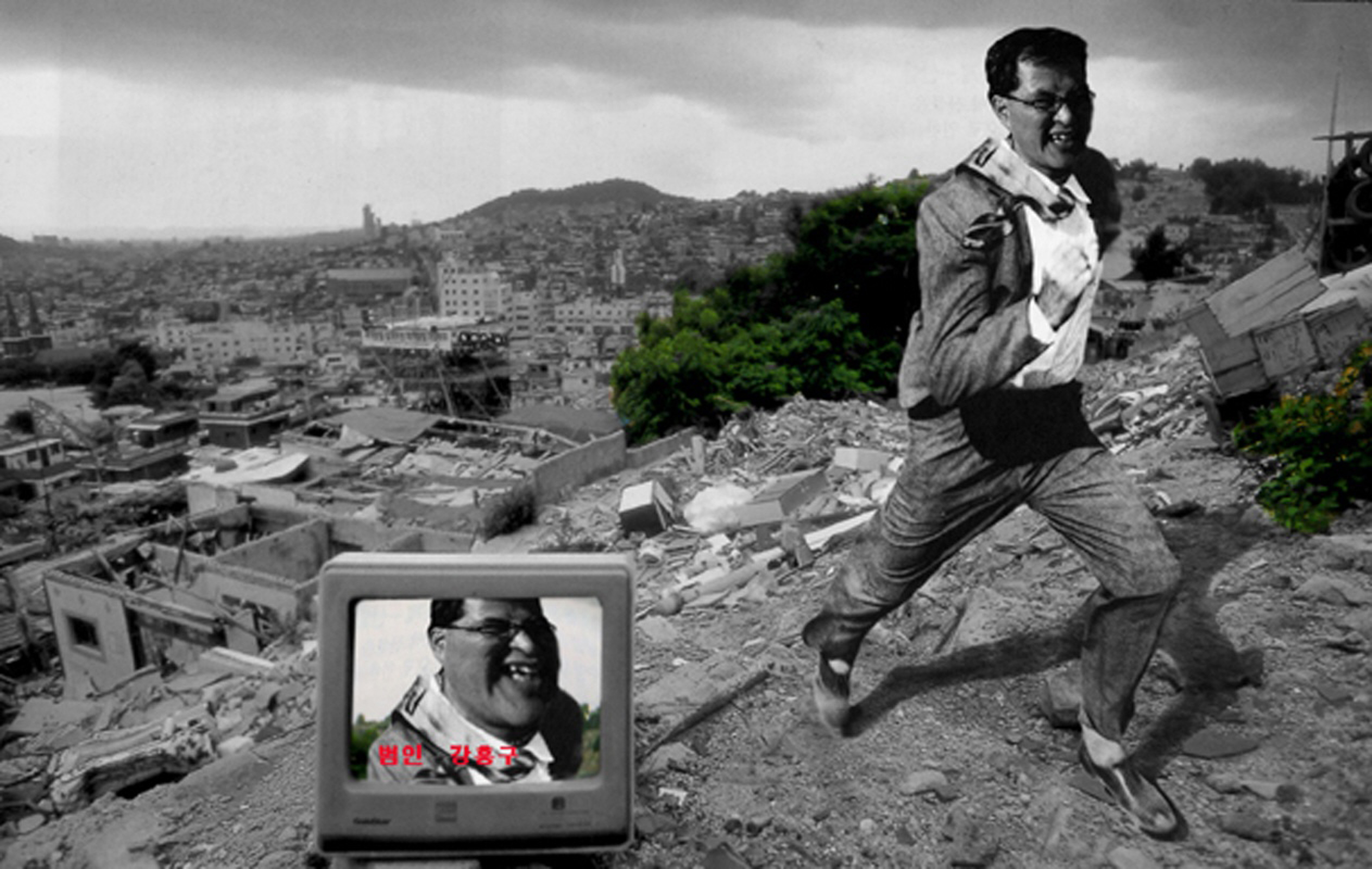

1. Kang

Hong-Goo’s photographs resemble dreams. Deserted streets

where time is lost, masses of dark shadows, and strange unidentifiable traces

in his photography recall the impressions of nightmares. But to say that Kang’s photographs resemble dreams isn’t to say

that his works represent the strange and familiar scenes we often experience

and ruminate on. It is not surface similarities but the structure of “dream work” that his photography

borrows, and furthermore, his photographic “therapy” is connected to the interpretation of dream.

In the ways the

narrative and imagery of a dream ingeniously utilize the techniques of

condensation, substitution, and symbolization to reconstitute the codes of

system and desire, capital and prophecy, Kang’s digital

photography composes landscapes and imaginations and histories. Brilliantly

burning trees, a row of architectural facades with no buildings behind them, a

giant barracuda plopped on a street, and someone’s

bizarrely elongated back lounging on a beach. These are some of the images that

Kang has borrowed from the techniques of dream. And it is through such

techniques that his photography suggests the entities that threaten us from all

sides in the reality in which we unwarily live in, or it suggests the condition

of that very threat.

Kang’s photographs, therefore, are not mere copies or scans of dreams as

they may seem at first glance. And here’s the reason

why the children’s story of the photo studio of dreams

cannot apply to his work. Kang’s photographs are dreams—or more precisely, the screens upon which dreams are projected. As

we enter the theater, we are confronted with bizarre, preposterous, and fearful

situations that unfold in front of our eyes in real time. His digital

photography is not premised on past tense, on which photography is

ontologically dependent, and a sorrow for things past, or its future-tense

form, i.e., death. In that his work is a present-tense experience of dreams, it

perhaps resembles cinema.

But Kang’s photography is

closer to a rear-screen projection made with light shone in front of the viewer’s eye than to the cinematic projection, in which light is thrown

from behind the viewer’s head. On the horizontal

widescreen of his photography, the viewer’s head-on

confrontation with the camera blurs the consistent focus of the image, and the

overlapping screens and obvious seams twist the retinal contemporaneity. Kang

obliquely comments that just as a dreamer does not make his dreams, the

photographer is not the agent of his photography. According to the artist’s “set-up,” we

the viewers build up spatially these present experiences, in which reality and

unreality, and guilt and desire crisscross. Kang’s

photography creates, just as our dreams do, architectural labyrinths in which

our bodies can spontaneously respond to crude, abrupt, and absurd situations.

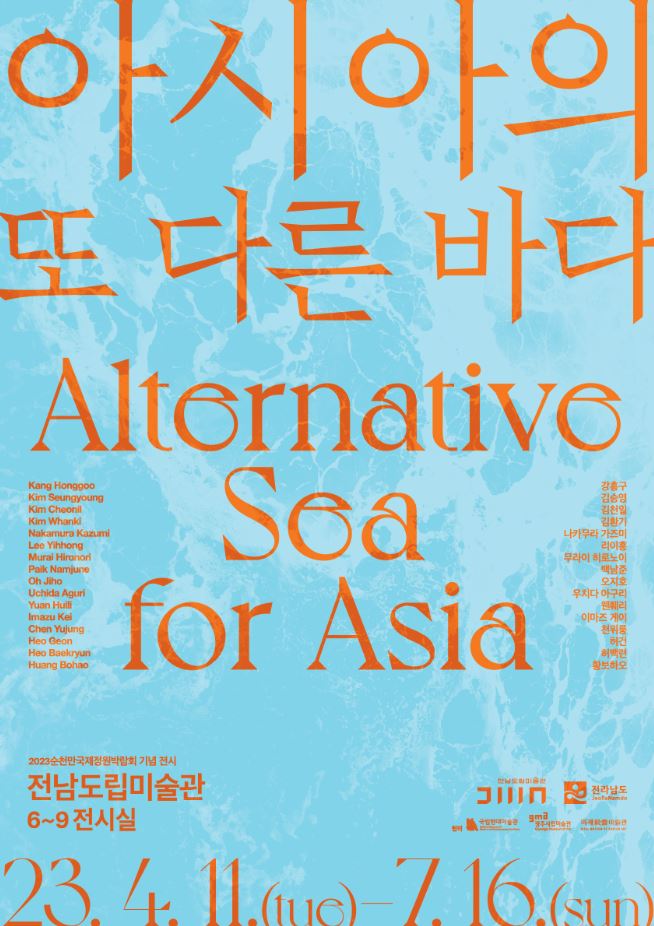

2. In

the present exhibition, viewers find lures that tempt them into a site of

super-fast demolition and super-sized construction where one may have an

experience of surrealistic sublime, a maze-like place that one cannot tell if

it is a dream or a reality. They are toys that the artist must have found on

construction sites in the periphery of a city. A toy house—called "Mickey’s House" because

Mickey Mouse is painted on it—sticks out among enormous

excavators and piles of scrap metals. Mickey’s house

appears in front of a row of houses on the brink of being reduced to powders,

on some precarious garden fence in a shantytown, on snow, or on a green lawn.

Even within a single scene, this toy house can function as a metaphor in the

sense of “Home Sweet Home” or

as a metonym in the sense that it is meant to belong to a household. In another

vein, it is an icon if the formal similarities were to be focused upon, and an

index when the generative relationship between the toy and the photograph is

considered. The toy house, which is especially outstanding against an

achromatic site of ruination and construction and the monochromatic nature

because of its brilliant palette, also operates as a kind of hypertext that

connects different individual photographs. Does this mean, then, that the

artist intends to play games of signs with this toy?

If

we were to make a distinction, the focus here should be on not sign but play.

In other words, the focus of this photographic series should be on the artist’s process—i.e., roaming around to find

the “found object” and

creating some witty simulations with it when he spots appropriate scenes. This

aspect of execution in the series is once more emphasized with the second toy,

which the artist has named the “trainee.” According to the artist’s research,

this toy takes its form from the fictional character Kazuya Mishima, a martial

arts warrior in a Japanese computer fighting game.

Kazuya jumps on dangerous

electric wires, hops over shattered glass, and climbs over precipitous walls.

Kang titles his photographs, in which this trainee’s

posture and size freely change, according to a lexicon of Chinese martial arts

novels. Following the trainee’s role-playings, viewers

see him in an encounter with Mickey’s house in one

scene, and while engrossed in such a visual pun, our eye often loses the

contexts that the toys are situated in and get comforted by the indexes, i.e.,

the toys.

In

this way, in Kang’s work is a

mixture of ideological signs, political landscapes, and the willfulness of

execution all mixed in different ratios. One of the most distinguishing

characteristics of his work is that it keeps pushing viewers outside its frame.

That is, objects like Mickey’s house and the trainee in

his digital pictures are read more productively alongside images, such as “squatter pics” or “required elements” on the DCinside

website, a ground zero in popular contemporary Korean visual culture.1) Seeing

Kang’s photographs one is naturally reminded of the

current social phenomenon of “digital invalids” abusing such images, and this is how the significance of Kang’s photography may be understood from a different angle.2)

Now that

the digital camera, the scanner, and the Photoshop have become cultural

necessities, and blogs and homepages constitute a standard of one’s social education, the drive that places his work in museums is not

the inertia within the art system that has made photography a viable artistic

medium but may be found in the power of cultural popularism that renders art’s courtship of photography powerless. And perhaps in an inverse

reaction, Kang, an artist especially sensitive to the speed of change in mass

media and technology, has fallen for the attraction of board games rather than

digital games; instead of creating manipulated images out of “required elements” with computer

programs, Kang has been capturing landscapes with actual toys. This capturing

also includes evidence of living in this era, in which distinction between

actual things and hybridized things itself has grown meaningless.

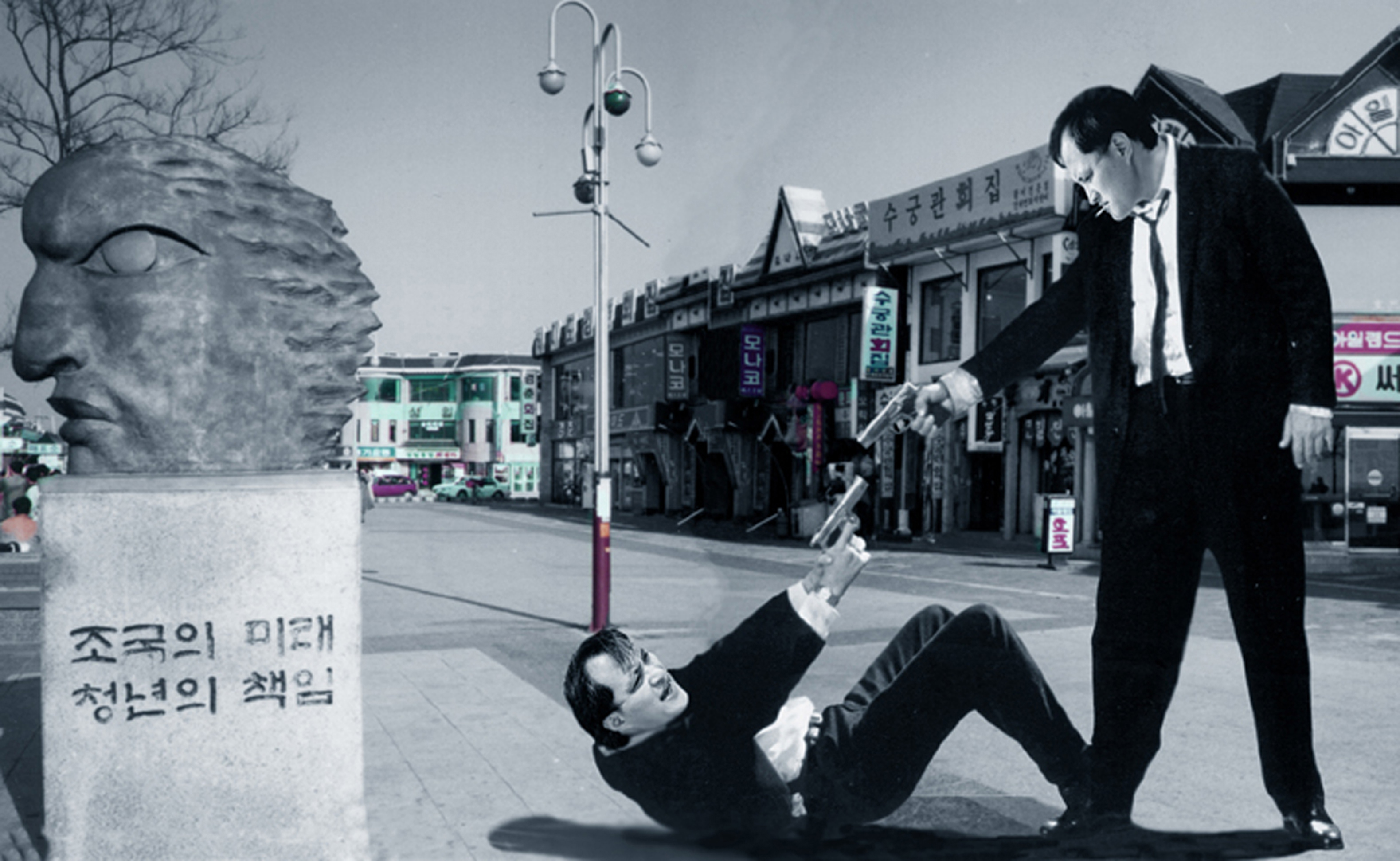

3. Kang

Hong-Goo is not only an artist but also an author of books on visual cultures

and has previously worked as a TV personality and a lecturer. In other words,

he has taken on multiple roles over the years. Fittingly for someone who has

mastered a variety of cultural texts including sci-fi movies, detective novels,

horror comics, and martial arts pulp fictions, Kang’s photography contains in it the artist’s

history of cultural education.

His cultural literacy, however, does not

manifests itself in his photography simply in terms of broadening the range of

references and selections but becomes more obvious in the ways in which he

practices intertextuality. While his work exhibits, for instance, a range and

diversity in its parodies and pastiches of Quentin Tarantino’s films, Manet’s nudes, Meindert Hobbema’s landscape of village roads, and Kim Jeong-Hee’s traditional Korean landscape, what is more notable is the ways and

processes in which these sources are quoted.

In

his earlier work, Kang often made photomontages, for instance, cutting and

pasting his own portraits within appropriated film stills, advertisements, and

other commercial images. This method of editing, which was limited to

juxtapositions and partial combinations of images evolved into a more complex

recombination of whole picture frames through overlappings and repetitions.

Consequently, he began to make his own photographs more frequently, and effects

such as exaggeration, distortion, shock, and alienation, rather than mere

collision began to characterize his work. Furthermore, as he started to apply

the more complex montage techniques which surpass typical genre films and

narrative conventions to horizontally expansive individual works and a series of

works produced around the same time, the series even earns certain

monumentality.

If

we consider Kang’s photomontages

with his own writings, the data he has collected, sketches, drawings, and still

photographs, his photographic theory seems to be more akin to John Heartfield’s rather than El Lissitzky’s. As art

historian and critic Benjamin Buchloh has argued, in the wake of Lissitzky,

photography, now as “factography,” has established a cultural literacy, with which it educates

the public. If the Russian avant-gardists aspired to supercede the material

limitations of constructivist sculpture by circulating thousands of

mass-produced photographs, in our era, digital photography has made possible a

single picture to self-replicate into thousands and distribute them in the same

resolution. Of course, Kang’s factography conjures a

far more dystopic vision than the utopian one of the Russian avant-gardes.

Kang’s panoramic photographs not only mobilize all kinds of texts before

and after themselves but also encompass sounds and smells. In that light, they

are quite multimedia. Especially notable from his body of work is the series of

images made from a town called Ohsoi-ri near the Gimpo Airport in Seoul. The

repetitive placement of an image of an airplane flying low through the series

of the landscapes of the town, which are all 280-centimeter long, effectively

conjures the effect of the oppressive loud noise an airplane would produce in

proximity.

The pool of water in which a dump truck has crashed is rendered with

an exaggerated perspectival technique, again making viewers effectively imagine

its rancid stench. While optically traveling through this landscape strewn with

piles of trash, fields of green onions, airplanes in the air, and discarded

shoes, all appearing in the same resolution, viewers feel with all senses the

fact that Ohsoi-ri has lost its placeness and has been absorbed into a temporal

zone of development.

This

naturally formed village, which is marked on the map only with the designation

of “Ohsoi Crossroads,” is

plainly edited into a space of future holocaust in Kang’s photomontage. The vanishing point in the photograph replaces the

town hall, from where one allegedly could have surveyed the whole village

visually, and becomes a symbol of the massive conspiracy of development. The

vanishing point of the perspective that organizes this image is emphasized like

the conspiracy theory that explains the whole world. It lucidly visualizes the

power behind the rumors that the townspeople were driven out by arson and that

even children were murdered. Just like all conspiracy theories, the vanishing

point in Kang’s photograph is indescribably seductive

and fatal.

4. Kang’s landscape photographs, as seen in the ‘Ohsoi-ri’ series, at first

glance seem composed around single viewpoints. But on closer inspection of

their operations, it becomes clear that their internal and external texts cross

with one another, imploding the perspectival spaces. The photographic

perspectives Kang realizes in his work often interfere with themselves, as

exemplified by Furgitive 8 (1999), a photographic

recreation of Hobbema’s painting, The

Alley at Middelharnis (1689); Kang obstructs the vanishing point

on the horizon line with a self-portrait.

This kind of “disruption operation” is also evident

in the artist’s trademark method of manipulated

composition. In his Who Am I series, the artist

replicates his self-portrait into multitudes, dispersing the viewer’s gaze throughout the picture. After graduating from handmade

processes to digital cameras and computers, Kang has been employing

picture-suturing as the main method of disrupting the viewer’s gaze. He states that his main objective there was to make

large-scale landscapes out of digital pictures. Although he has not been able

to accomplish the objective due to technical and financial reasons, he was able

to create, after quite a few trials and errors, stitched, horizontally

expansive landscapes that are panoramic in effect.

In

terms of the way of seeing that is required, panorama pictures share

similarities with handscroll paintings. While most of Kang’s photographs are shown in full lengths, viewers can rarely see the

whole pictures in a single viewing. Consequently, they can view only sections

and must put them together in continuum like the frames of a moving picture.

In

Kang’s panoramas, the viewer’s

gaze encounters each one of different camera gazes that are sutured in

individual frames, which are slightly overlaid upon one another or distorted.

The eye scans these long pictures from left to right—or

in the opposite direction—in “temporal” manners. There is the obvious

distinction, of course, in that one views a handscroll painting by rolling and

unrolling, while a panoramic photograph is seen by the viewer’s body moving along the length of it.

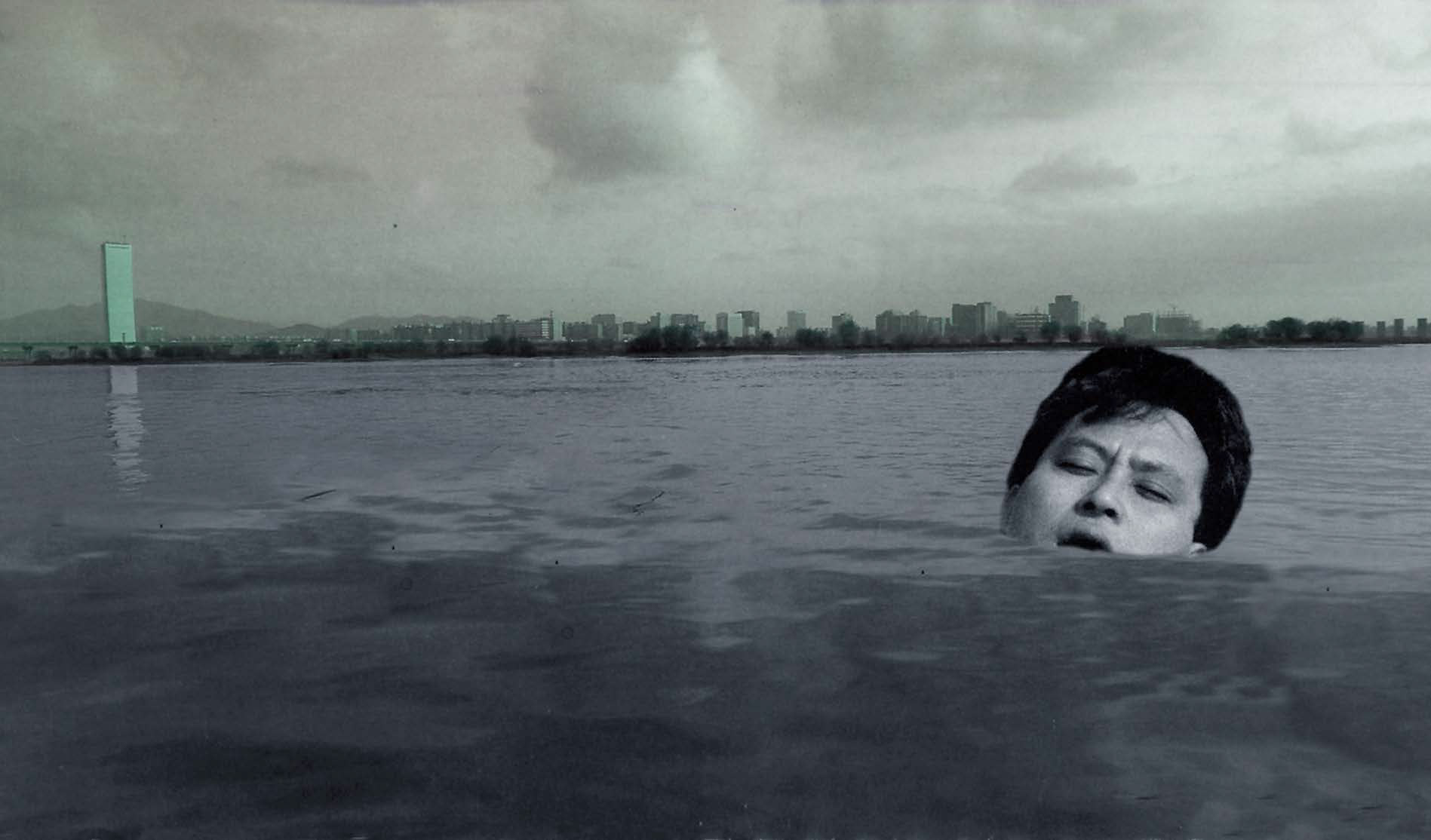

The

most representative handscroll-style photographs in Kang’s work can be found in the The Han River Public Park series.

Presenting group portraits of people enjoying walks in the park with distant

sights of skyscrapers and massive bridges in the backdrops, these photographs

may be considered a kind of typical genre pictures on the subject of a lazy

holiday. Strewn with people bearing comic facial expressions, pairs of lovers

and groups of friends, homeless and drunkards, and periodical appearances of

Ronald McDonalds and flying kites, all of which are unfailingly captured by a

relaxed camera’s eye, these pictures provide much to

read for viewers.

Here,

what grabs our gazes and guides the temporality of visual appreciation in this

over-five-meter-long panoramic picture is not the several vanishing points

marking the picture but the horizon where the river and the park meet. The

method of viewing required by this beautiful landscape—one follows the picture horizontally following the flow of the river—places The Han River Public Park less

close to Impressionist paintings of parks than to traditional scroll paintings

like Jang Taik-Dan’s Chungmyung

sangha-do, which the viewer unrolls into a section of a manageable

length at a time to see unfolding scenes of transportation of cargos, changing

lifestyles and households, and streets tightly surrounded by buildings.

Admittedly, to make this comparison only based on similar viewing experiences

while ignoring the obvious differences in terms of time, location, and medium

might be a risky set-up for understanding broadly the work in question. In that

sense, perhaps better comparisons may be found in a tourist village that

recently opened in China or the film set for a recent Korean movie with a

storyline set in the Song Dynasty, both of which are based on Jang’s handscroll painting. At the same time, Kang’s photographic series, in ways that are highly distinct from such

realizations or physicalizations, creates a kaleidoscopic world that can

broadly address traditional genre painting, its epistemes and structures of

sensibilities, and even the self-referentiality of mass media.

5. Is

the film set, said to be based on the streets depicted in the handscroll

painting, a fiction? If people can enter to enjoy the view of the set, does it

become a reality? Is the “fantasy-action-melodrama” said to be being shot in the set a fiction? If the movie is

actually made and widely released, is the theater showing the movie real? Or,

is the handscroll painting, which creates this endless linkage of

representation of representation, an original? Or is it a copy of something

else?

Pressing “pause” on

this dizzying series of questions and playing the landscapes we are looking at

frame by frame in a slow motion—this is how Kang’s series of drama sets operates. Kang made the series by taking

pictures of sets “in actuality.” As seen in the images per se, these sets, which were created

for historical or martial arts dramas, do not look anything like what we

encounter when watching the films and TV dramas. Aided by the intervention of

high-definition cameras, editing techniques, and cutting-edge computer graphics,

films and dramas these days reveal very few detectible fissures or seams.

In

Kang’s photographs, it is the “dross in gold” one would seldom see in

movies and dramas that takes the center stage. Soaring apartment buildings are

visible in the far background of the TV drama Age of Outsiders,

and people dressed in current fashions along with cars appear in a scene

supposedly set in Japanese colonial period. Even worse, one of the photographs

zooms in on the backside of the façade of a mock Dongdaemun and a pile of trash

thrown in front of it.

Kang even leaves the seams and traces of the suturing of

these pictures. These anachronistic indexes dispel the usual effects of

black-and-white photographs—taste for things past,

symptoms of art photography, and evocation of nostalgia. In such ways, Kang’s photographs of drama sets distort the future tense of digital

photography, which seems to exponentially self-replicate, and the past tense of

slowly discoloring black-and-white photography.

All

of Kang’s landscape photographs are captured by the

artist busy on his feet on a variety of contemporary sites from nearby towns to

distant tourist spots. As if a documentary photographer, he deals with

the “existence” of

contemporary sites and specific incidents or people. Paradoxically, however,

these landscapes all appear as if they have been just excavated after having

been submerged under water for a long time. One sees deserted, desolate

streets, garbage stuck here and there like waterweeds and mosses, collapsed

buildings, and mere traces of urban structures, and the survivors roaming these

scenes of devastation seem like mummies that are just awakened. In the

submerged landscapes, Ohsoi-ri and Apgujong become sites for pillaging, and Sehando

and Gosagwansudo turn into plunders.

Through

its era of development in Korea, the monstrous forces of the desire for

super-modernity, imagination of civil engineering, and economic fascism have

razed or sunk peopled towns and storied villages. As if nothing had happened,

then, high-rise buildings and massive apartment complexes are built up, or

highways and dams are laid down. In recent years, the former sets of popular TV

dramas and movies have become tourist spots, bringing considerable profits to

local governments.

In a similar way, those places that have been sunk in

sacrifices may one day emerge like ghosts and start attracting people to them.

Finally, our dreams and unconscious have turned into currencies—no paper money but those that circulate invisibly via the magnetic

strip of the credit card and the bytes of the Internet banking. Are all these

waking dreams, or precognitive dreams, or deja-vus? That’s what Kang Hong-Goo’s photograph keeps

asking us.