Kang

Hong-Goo’s practice begins with revealing the hidden side of reality that we

believe we are seeing through photography—that is, the social and political

conditions that are naturally consumed and passed over in everyday life. He has

used photography not as a simple recording medium, but as a tool that prompts

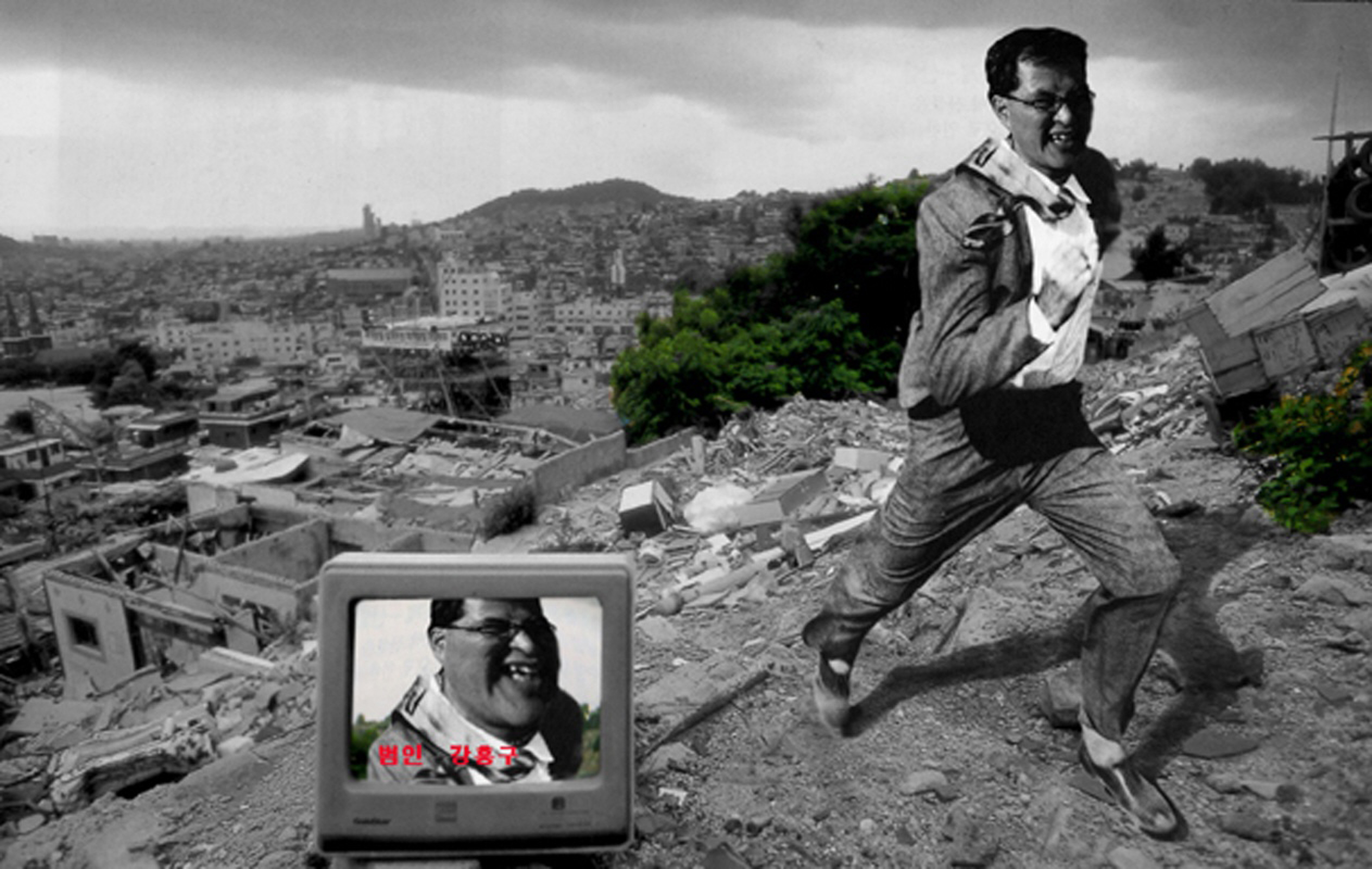

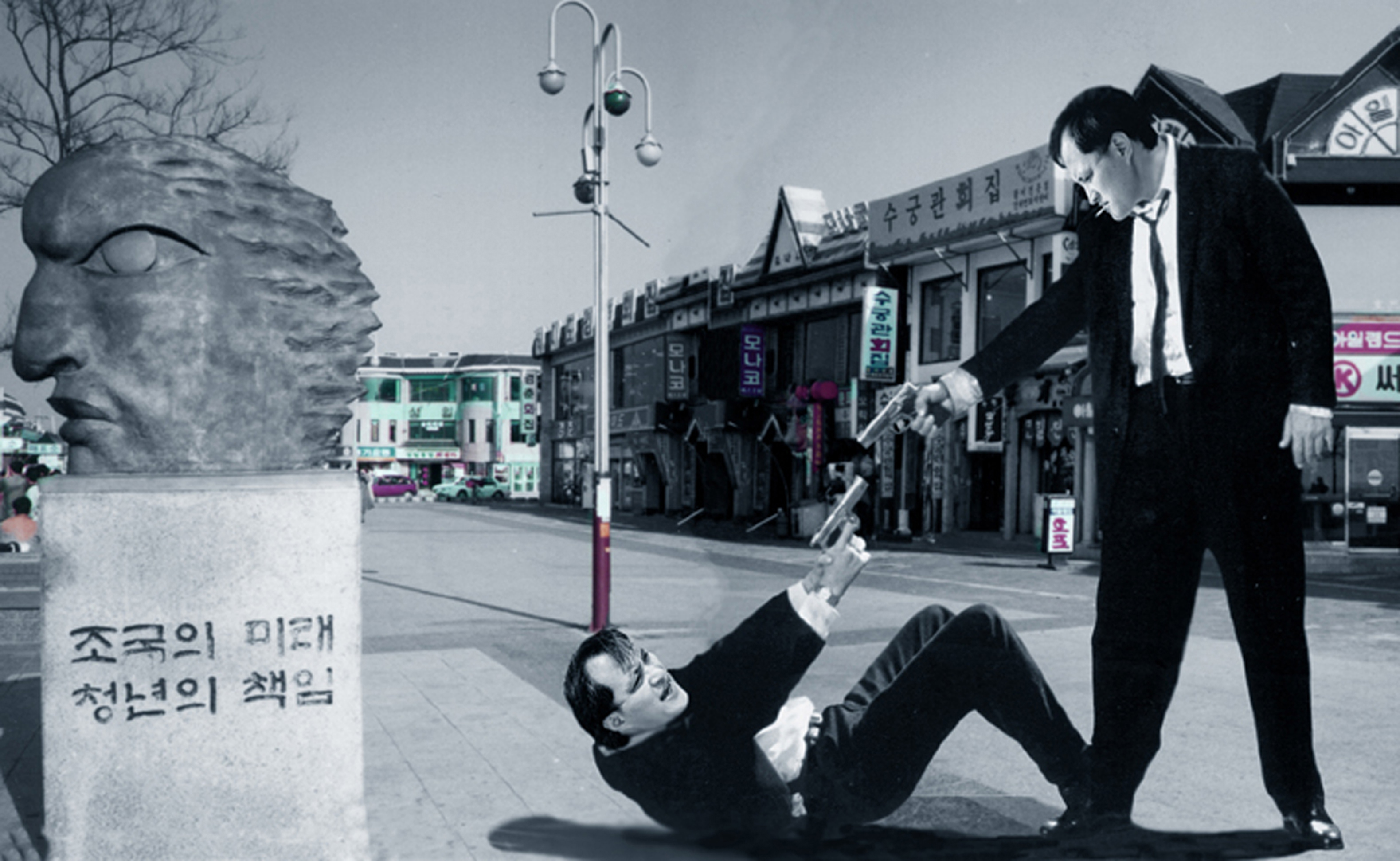

us to doubt a reality already manipulated and constructed. From the mid-1990s

composite-photo series ‘Who Am I’ (1996–1997) and ‘Fugitive’ (1996), the artist

questioned how images conceal or distort desire, power, and historical memory.

‘Fugitive,’ in particular, originated in a personal sense of indebtedness to

the May 18 Gwangju Democratic Uprising, visualizing the helplessness and

impulse to flee that an individual feels in the face of historical violence.

Kang’s

focus subsequently expanded from questions of personal identity to space and

everyday life within social structures. ‘Greenbelt’ (1999–2000), ‘Landscape of

Oshoeri’ (early 2000s), and ‘Drama Set’ (2002) capture the contradictions of

spaces produced by systems of development, regulation, and media production. In

these works, Kang exposes the gap between institutional language and actual

landscapes—such as greenbelts rendered desolate under the pretext of

“preservation,” or drama sets where the boundary between reality and fiction

collapses. Rather than simple oppositions, he presents relationships between

city and nature, reality and representation as states of disjunction.

From the

mid-2000s onward, urban redevelopment series form the core axis of Kang’s

practice. ‘Mickey’s House’ (2005–2006), ‘Trainee’ (2005–2006), and the

long-term project ‘Chronicle of Eunpyeong New Town’ (2001–2015) trace villages

and traces of life erased by redevelopment. Going beyond straightforward

documentation, these works reveal the violence normalized in the name of

development and the memories excluded in the process, destabilizing the

assumption that photography simply presents “facts.”

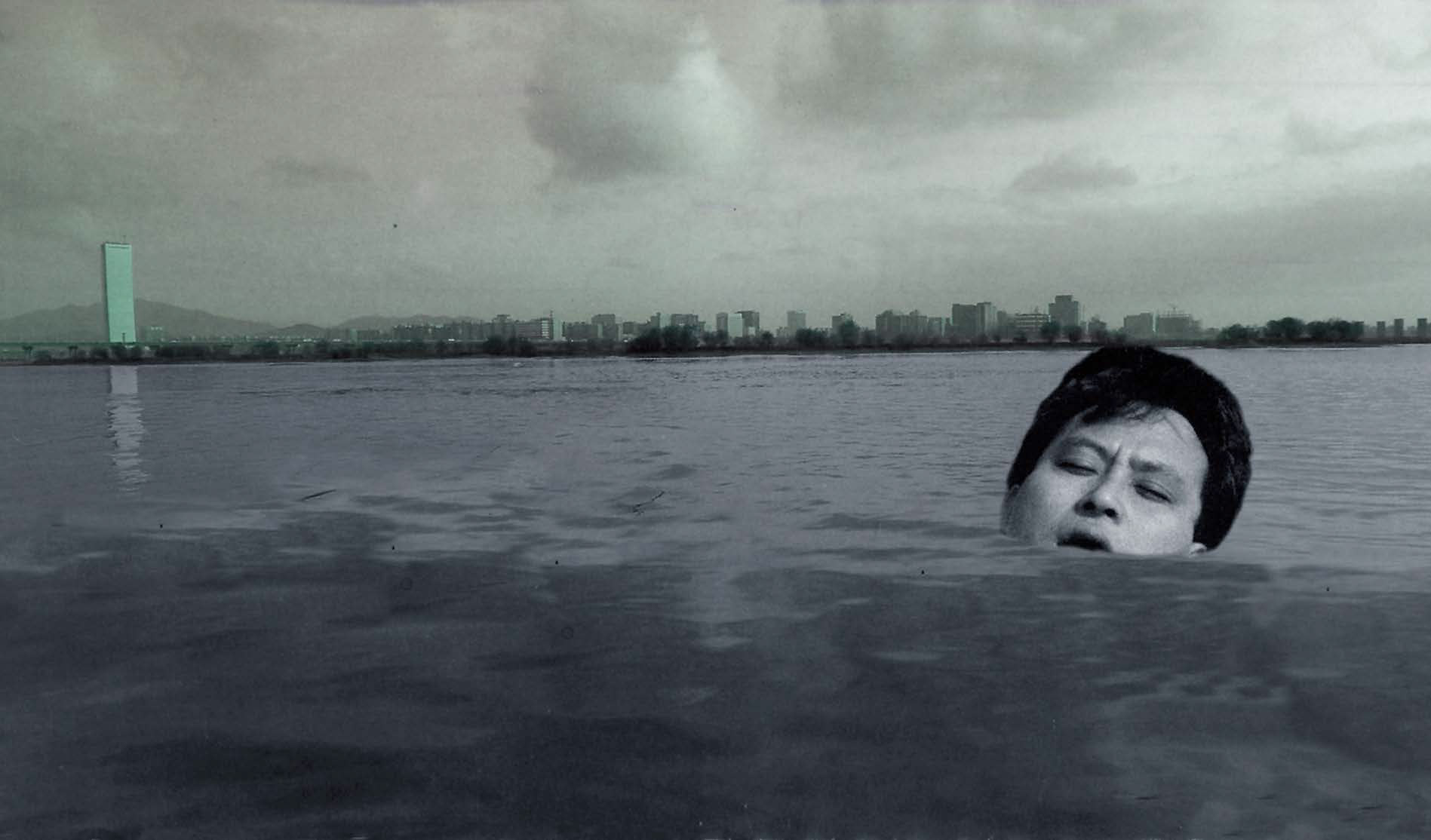

In the

more recent ‘Shinan Sea’ (2005–2022) and ‘Clouds, Sea’ (2023– ) series, Kang

turns his gaze back to his hometown of Shinan. While addressing island

landscapes transformed by development and tourism, these works extend concerns

accumulated in the urban redevelopment series by combining them with personal

memory. Here, landscape no longer functions solely as an object of social

critique, but as a site where memory and the present, insider and outsider

perspectives, overlap.