Where

do a black sphere brutally made of 16 tons of cast iron and less than 1 gram of

coal tar solution meet? Where do an old railroad sleeper—its entire body

cracked open and its crevices soaked with thick black grease—and a pitch-black

lump of coal, so dense that there is not even space to stick a needle, find a

point of contact? Is it because all of them outwardly reveal their powerful

material properties more strongly than other mundane objects?

Or is it because,

from the standpoint of the person encountering them, they appear as masses,

densities, volumes, colors, and forms that differ from one another yet are

equally intense and stimulating in terms of perceptual force? Depending on

one’s perspective, many relationships can be imagined. But in the case of the

artist Chung Hyun, they meet on the horizon of sculpture. And these

materials—laden with excess intensity and expressiveness—form points of contact

in Chung Hyun’s creative world as motifs (signifiers) that visualize the

fundamental and real artistic theme (signified) of the “human.”

Yet

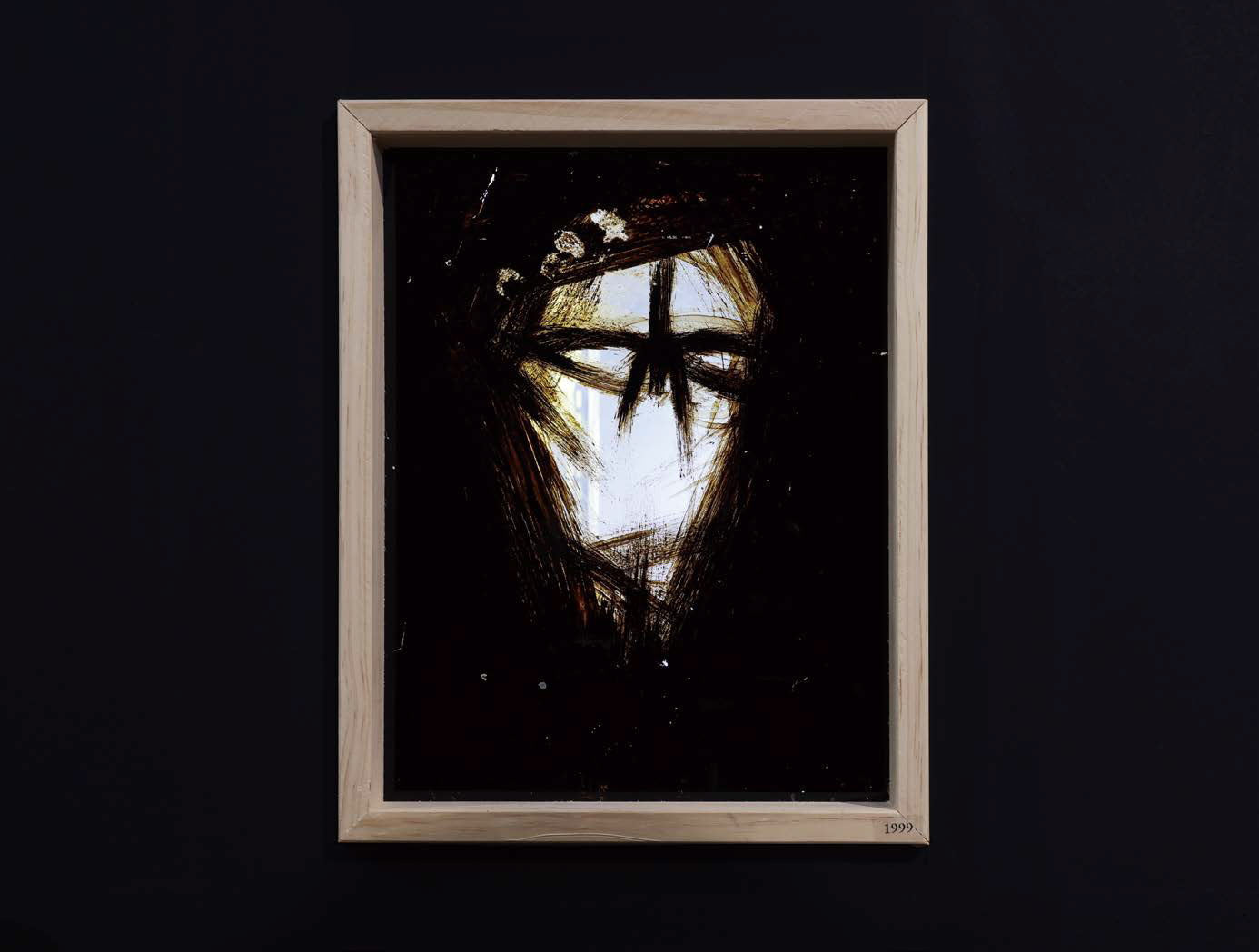

I do not try to see the human body in his sculptures. Nor do I try to see the

human face in his drawings. As a viewer, I do not wish to weaken the

overwhelming material presence his works emit, the visual expressiveness that

renders language tenuous, or the power of installation that induces a literal

encounter with the viewer, by reducing them to human meaning or narrative

context.

For instance, I do not wish to analogize the process by which a

so-called “crusher ball”—used by a major domestic steel company—was dropped

vertically from a height of 25 meters for over ten years to purify impurities

in iron, being exhausted from 16 tons to 8 tons, with the history of human

trials and tribulations. Nor do I wish to interpret railroad sleepers that have

borne the full weight of passing trains for decades as ontological metaphors

for human destiny crushed by the weight of life, or to liken tangled, dark-red

rusted rebars to the bitterness and hardship of human existence. Such

interpretations, after all, easily lapse into sentimentalism and end up

offering only clichéd consolation.

However,

regardless of my critical inclination—or even prior to such a level—the artist

may well have created his works out of a deep affection for humanity from the

outset. Alternatively, he may have grounded the value of his work in

face-to-face encounters and communion between humans and human forms. This is

because the artist once said the following: “I try to draw closer to the

desperate, moment-by-moment states of human existence in this age of

obsession—moments that are pierced through, torn apart, and distorted.”

This

sentence, excerpted from a text Chung Hyun contributed to Monthly

Art in 1992, seems to reveal what the sculptor sought to visualize through

tactile modes of expression: beating heavy lumps of clay with wooden beams,

chiseling rigid chunks of coal bit by bit, and smearing sticky coal tar across

paper. What he aimed to visualize, and where he sought to arrive, appears

unambiguous in context: to rhetorically render human existential suffering in

visual terms, and through that, to achieve a humanistic art. Thus, I—who tried

to avoid the human in his art out of fear of slipping into cloying

sentimentalism—was mistaken.

Precise Projection of Material and Human

But

is it because Chung Hyun’s sculptures metaphorize the human that we find them

compelling? Are they moving because they soothe the viewer’s humanistic

sensibilities? Even if both are true, are they sufficient? Until now, both the

artist himself and many commentators have almost without exception discovered

values oriented toward humanity in his work, or conversely defined his

aesthetic world through humanistic values. Yet there is an aspect of Chung

Hyun’s sculpture—one that cannot be concealed or diminished—that seems

impossible to illuminate through such circular reasoning or domesticated

humanism.

I believe this is because the objecthood of things

themselves, performance itself, and the order of

things themselves constitute one of the absolute properties crystallizing

Chung Hyun’s art. These are objects that cannot be captured within an

anthropocentric web of meaning. How could we humanly appropriate the

qualitative state of asphalt concrete used for paving roads, the magnitude of

pressure exerted on railway sleepers, or the temporality and ecology of metals

that rust, decay, and erupt in red lesions? Even if, through the intervention

of an artist named Chung Hyun, such materials become sculptures reminiscent of

a mountain-like reclining human body, installations that evoke groups of humans

standing firmly on the earth, or even figures recalling Giacometti’s emaciated

standing men.

Of

course, such discussion must be balanced by examining how the artist’s work has

unfolded over time. In 2006, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary

Art, Korea selected Chung Hyun as Artist of the Year, held a solo exhibition,

and published a catalogue. In her essay, curator Park Su-jin explained his

artistic trajectory as follows: “From the late 1980s through the 1990s, the

dynamism of the human body formed the core of expression. From the mid-1990s

onward, materials and tools became central, revealing chance elements in the

production process. Particularly in the late 1990s, materiality itself became

increasingly emphasized.” I agree with this periodization. Yet considering the

artist’s recent works as of 2014, the core of this transformation can be

articulated more precisely.

In

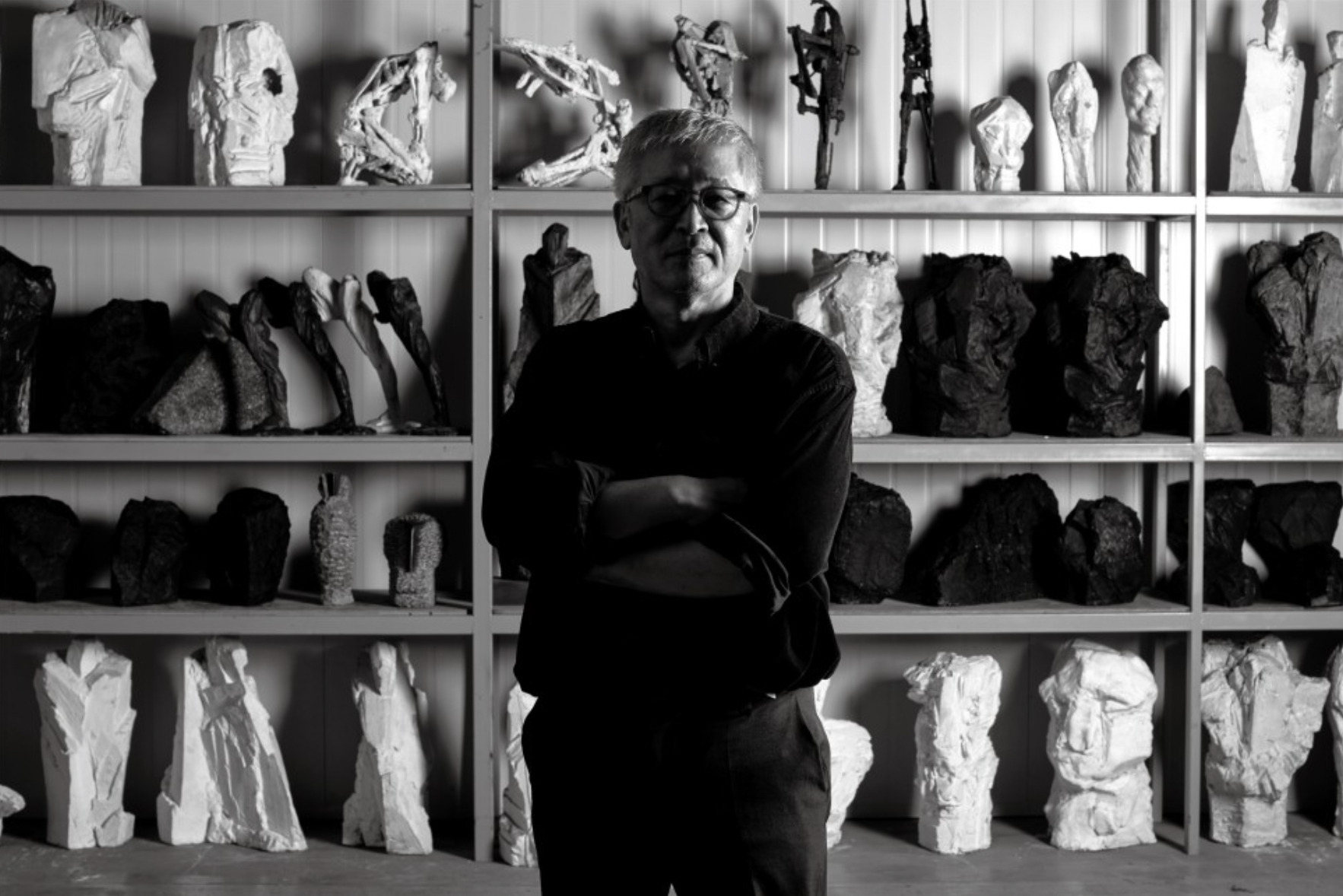

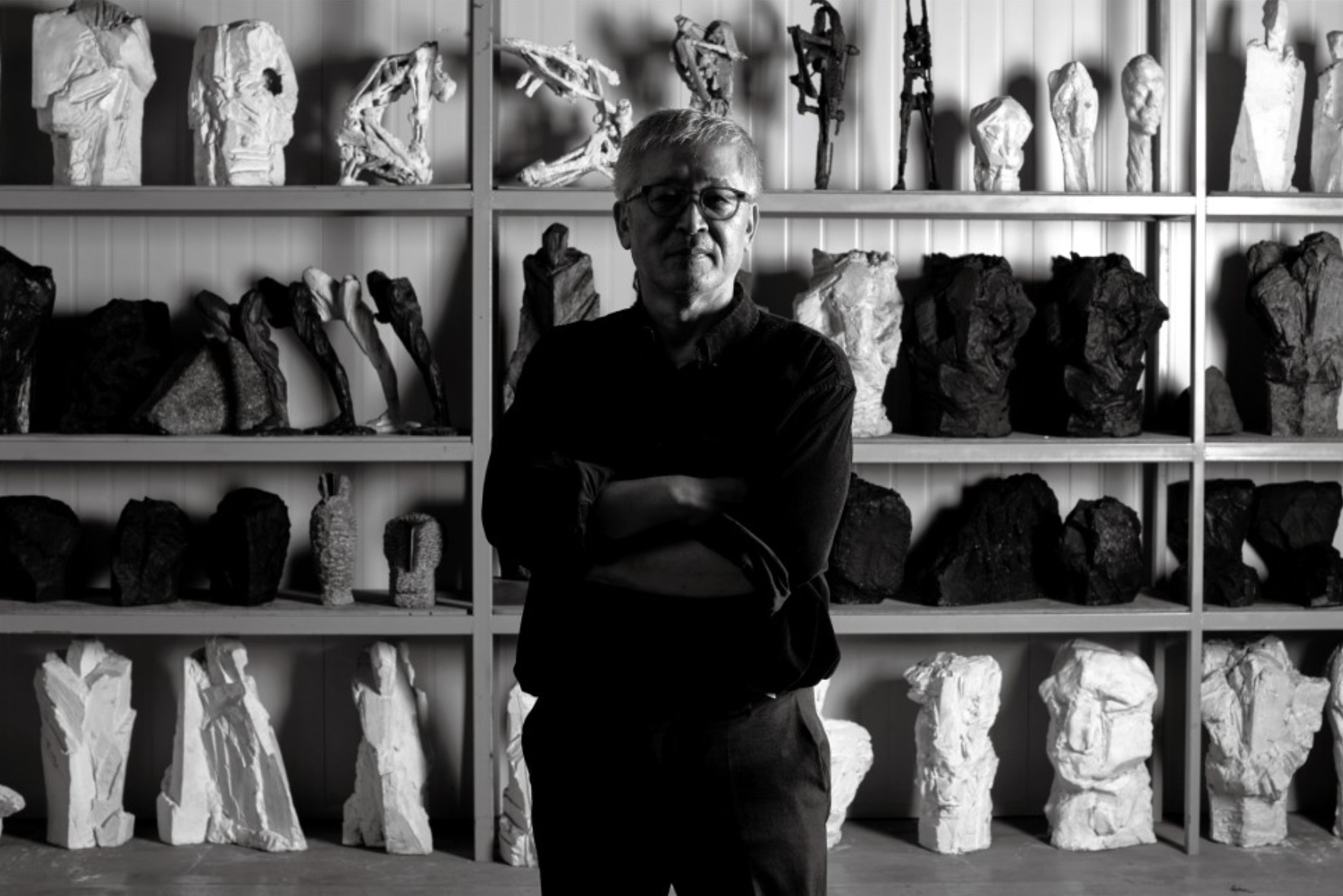

short, during his early period—when he focused on human figures constructed by

coating manila hemp armatures with plaster and coloring them with coal

tar—Chung Hyun indeed governed materials under the name of art in order to

shape the human form. Gradually, however, he transitioned toward allowing his

artistic intention and expressive mode to echo the inherent

properties of materials and the contingent, variable external conditions

surrounding them. That is, he moved from subordinating materials to his sculptural

objectives—crafting forms that resembled humans visually or symbolically—to

responding, like reverberation, to the characteristics emitted by materials

themselves and their surrounding contexts.

Arguably,

with the work ‘8-Ton Crusher Ball’ presented in his 17th solo

exhibition, Chung Hyun’s sculpture approaches an almost complete form of art

that presents things as things—objects that can only be experienced in their

given existence and order. This is an art that affirms a material’s inherent

properties, appearance, and the total history it has endured in its entirety,

prior to any anthropomorphic appropriation or human-centered interpretation. Is

such art non-human? Is the human absent from it? No. Just as human figures are

implicit in his sculptures of the 1980s and 1990s, and intense human faces are

evoked in his recent drawings, the human remains a fundamental axis embedded in

his recent sculptures—even in works that are, materially speaking, nothing but

matter itself. What has changed is the mode of relation.

Where

earlier works sought creative significance in dissolving materiality to

symbolize, express, and abstract the human, the current works aim for an

immediate and literal human resonance in response to material. The

first human in this resonance is the artist himself—the one who encounters the

material and discovers the possibility of art within it. But once such

material, as a kind of “found object,” is presented as an artwork, any viewer

can become that human.

Confronting

the massive black crusher ball—with its immense size and weight, its solidity,

and yet its smoothness and austerity honed over long years like a pebble shaped

by a river—the viewer’s nervous system responds to the object’s objecthood,

forming a particular image. We may be tempted to say that this image is freely

imagined according to the viewer’s subjective interpretation, but this is not

entirely true.

A

massive cast-iron sphere, physically worn down through countless aerial drops

over ten years, evokes in viewers both an unapproachable dignity and an

indescribably condensed pain. This is not because viewers imaginatively assign

meaning to it (though we tend to believe so), but because they are

responding—often unconsciously—to the object’s present qualitative and physical

condition. The grounds of this judgment do not lie in the viewer’s subjectivity

or psychology, but emerge from the object’s material state, manifesting in the

viewer’s perception and consciousness. For this reason, I propose applying the

term echography to some of Chung Hyun’s sculptures.

Echography,

in medicine, refers to diagnostic methods such as ultrasound imaging—techniques

that reveal internal bodily conditions invisible to the naked eye through

echo-graphs generated by high-frequency waves, as in prenatal ultrasound

images. Jacques Derrida introduced this concept into philosophical debate to

analyze interactions between humans and television. Similarly, I infer that an

echographic process first operates between Chung Hyun and the materials of

reality he attends to, and further between the aesthetic experience of

potential viewers and the materials presented as matter itself.

When the artist

speaks of a half-eroded crusher ball, dismantled sleepers, or broken rebar

joints as “beautifully endured trials,” that beauty is not anthropomorphized;

it is the qualitative and formal state of matter projected onto the eyes and

skin of a human named Chung Hyun These materials appear before us temporarily,

yet they exist as they are through their own histories. Even when we think we

are judging them as such, it is in fact they that cause us to feel and think in

this way. By reversing and complicating the subject–object relation of beauty,

Chung Hyun’s recent works invite a critical framework in which the “human” is

newly rendered through another echography of perception.