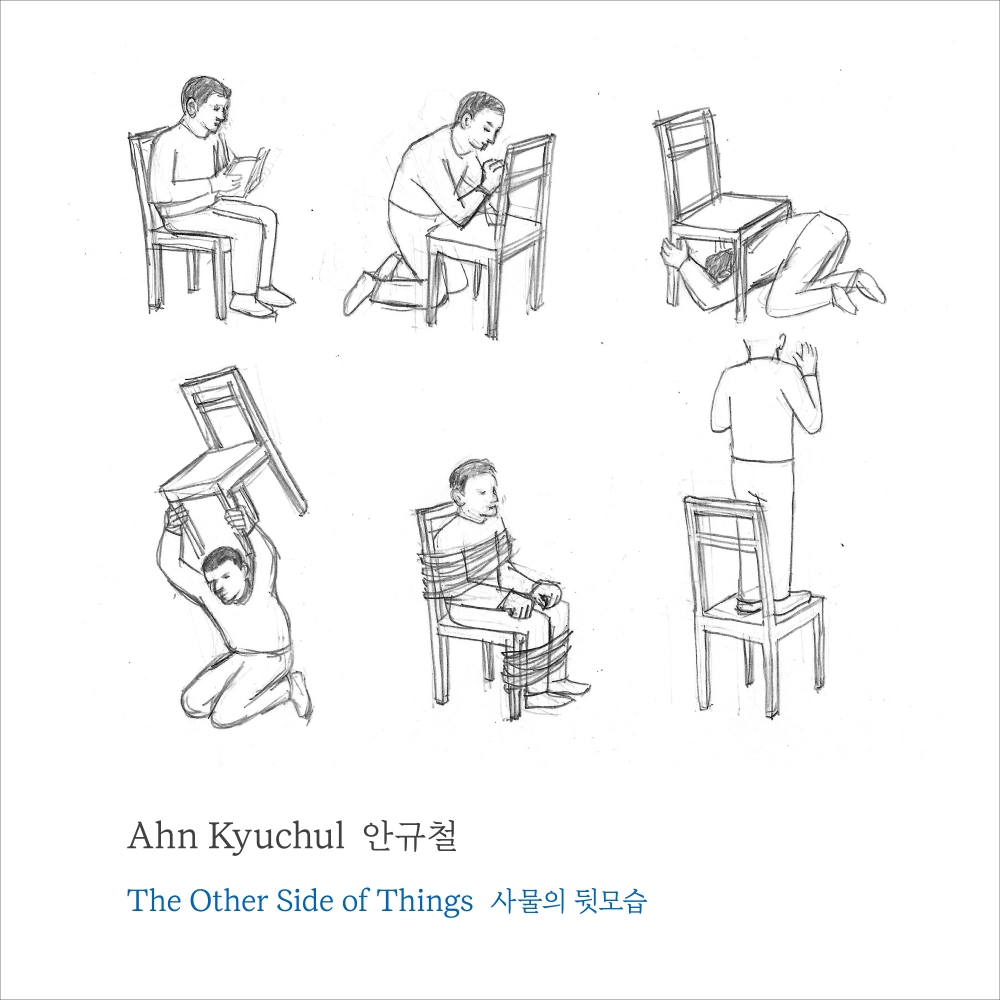

The eight works presented in this exhibition, including new pieces,

exemplify the artist’s longstanding tendency to infuse sculptural practice with

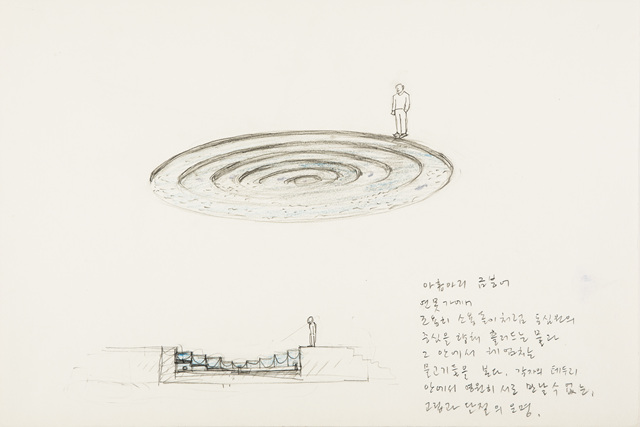

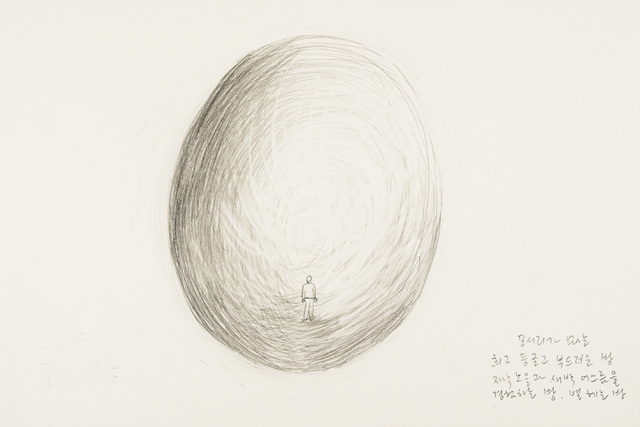

literary—particularly poetic—sensibility. His numerous drawings, often included

as supplementary exhibition materials, function as a vast reservoir from which

works can be realized at scales ranging from small objects to architectural

structures. These drawings—composed of text and image, or drawings that

themselves perform the role of text—span everything from ideas possible only in

imagination to meticulously detailed plans.

Many of them have likely never been

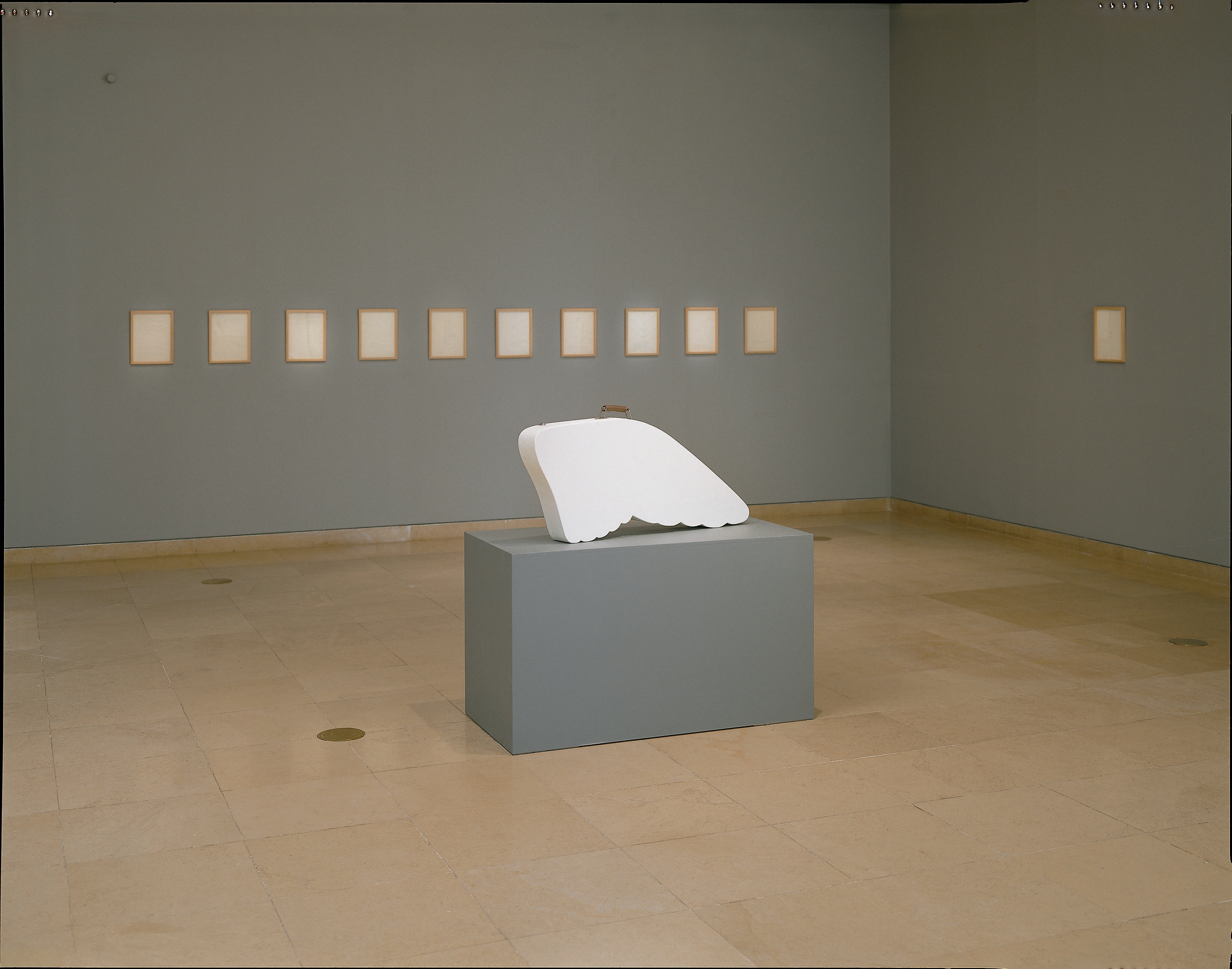

realized. In this exhibition, however, supported by corporate sponsorship,

several of these ideas have moved beyond paper, passing through processes of

design and construction to be monumentalized within physical space. The

exhibition hall itself has been entirely reconfigured, from floor to ceiling,

with careful calculation of the viewer’s movement.

The condition of the floor,

the moment when stairs appear, and even the actions anticipated once the viewer

enters a staged space have all been precisely considered. Unlike much so-called

“conceptual art,” which prioritizes ideas while neglecting the concrete

processes needed to embody them—often resulting in the obscuring of the

original concept—Ahn Kyuchul’s exhibition is distinguished by the solidity and

rigor of its mechanisms.

A Bridge from Drawing and Literature to Plastic Arts

The first work encountered by visitors, Nine

Goldfish, consists of goldfish swimming within a tank divided into

nine concentric circular compartments. Though sharing a single center, this

stratified structure confines each fish to its own orbit, preventing free

movement or mingling. It serves as a metaphor for life in partitioned spaces—an

ambiguous condition that is neither fully communal nor fully individual, yet

uncannily similar to our everyday reality.

Under the vision that such a mode of

existence should be overcome, the work gestures—if only temporarily—toward the

possibility of community. The subsequent work, The Pianist and the

Tuner, stages a peculiar performance. Over the course of the

exhibition’s 132 days, a pianist arrives each day at a fixed time to play the

same piece, while a tuner likewise arrives daily to remove a single component

from the piano.

Gradually, as the parts that constitute the whole disappear one

by one, the situation becomes bleak—perhaps even catastrophic—re-enacting, in a

somewhat mechanical fashion, a condition in which no action can ultimately

produce any effect. The performance does not end in silence so much as it ends

by performing silence.