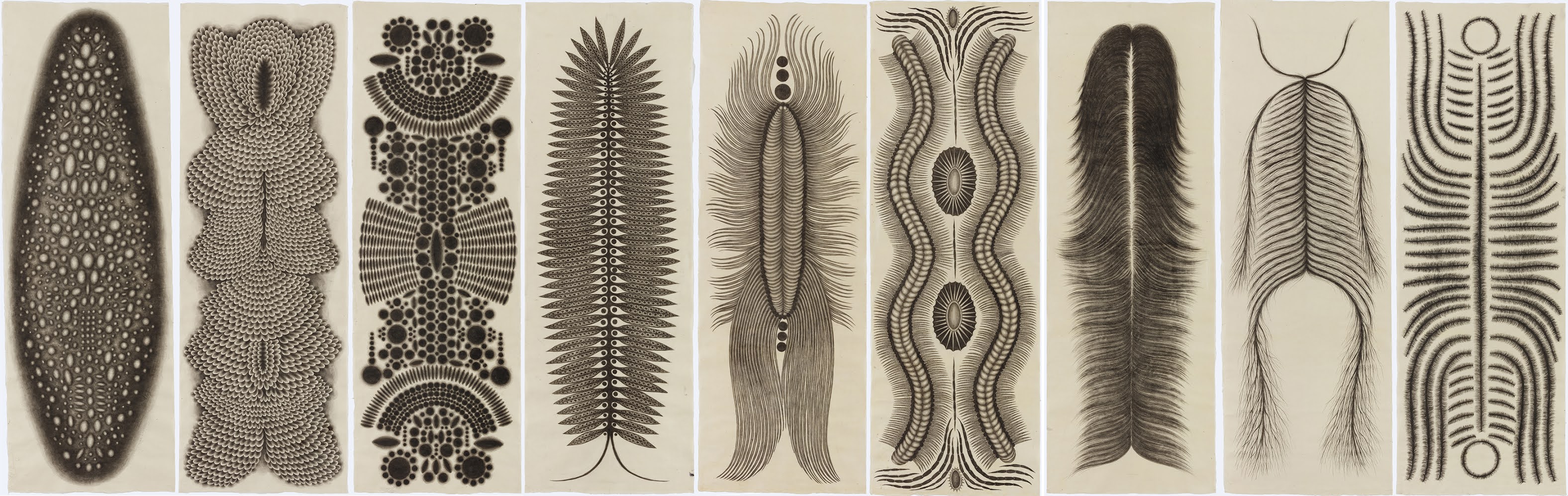

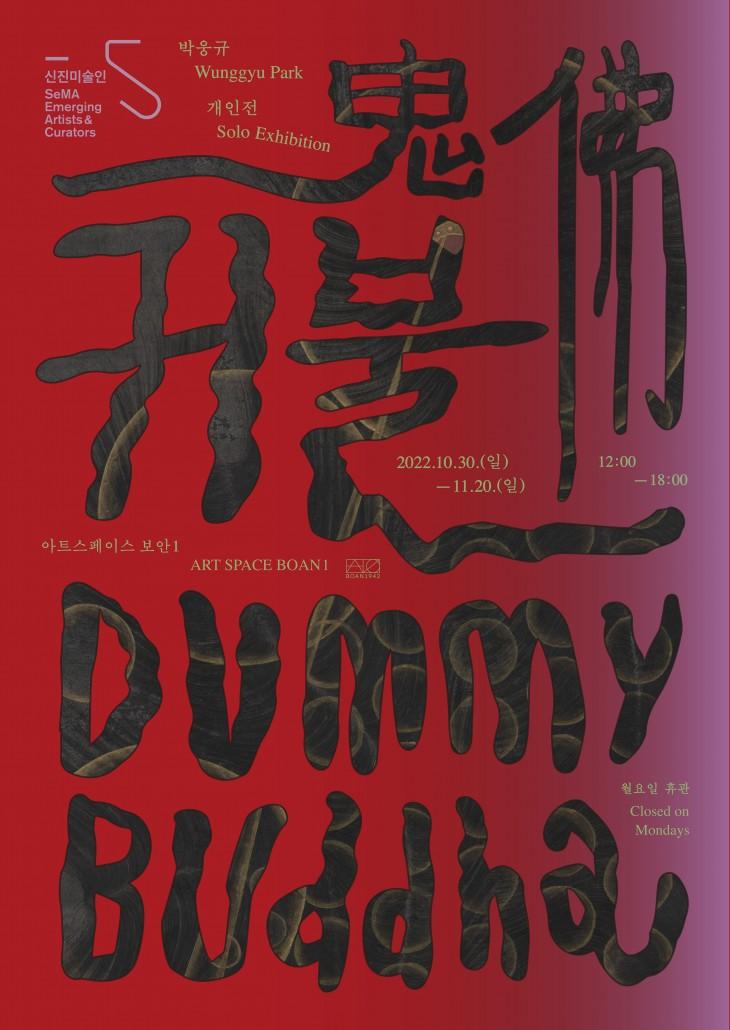

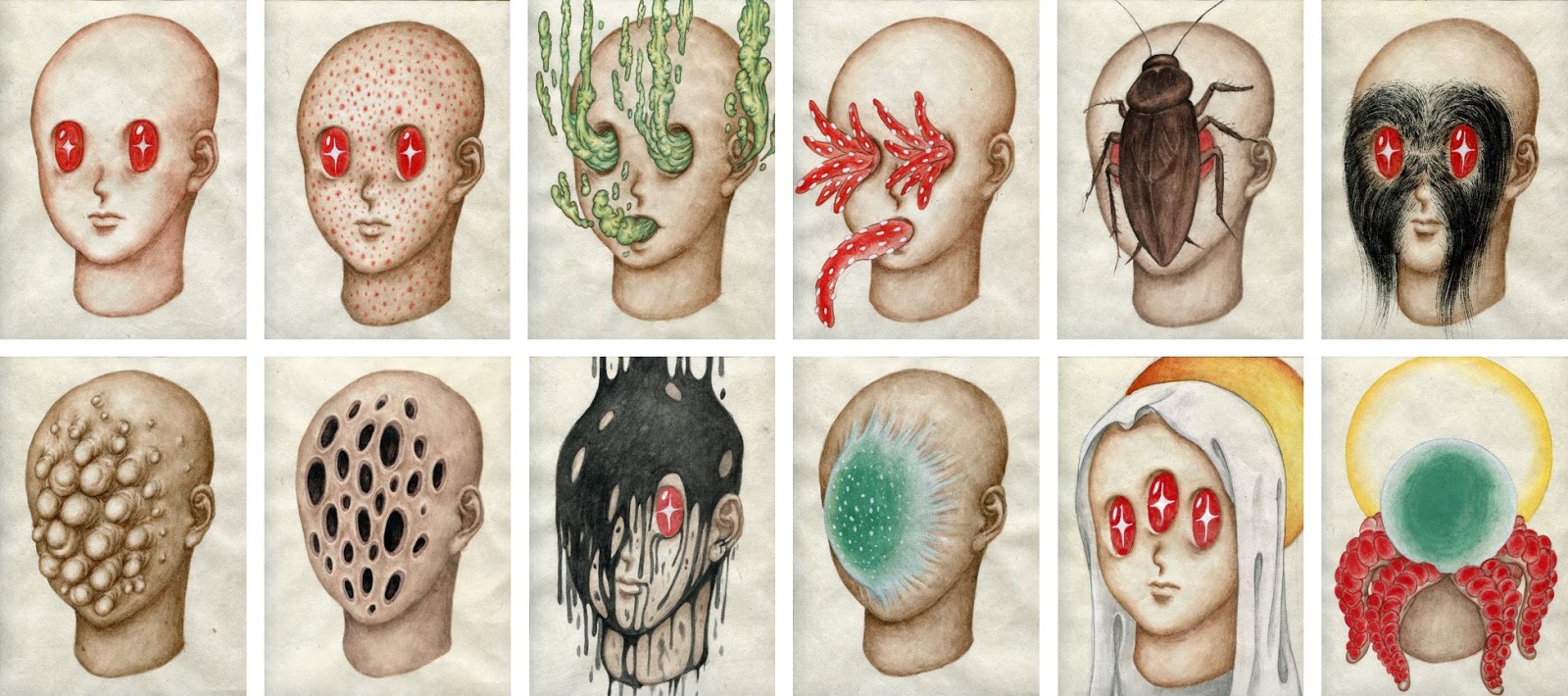

Comprising

a total of nine pieces, the series ‘Dummy’ originated from the Buddhist

painting known as Nine Pieces of the Dummy (Nine Stages of a

Decaying Corpse). This traditional painting illustrates the process of a human

body decaying into dust in nine distinct stages, encapsulating the essence of

Buddhist philosophy—namely, the transience of desire. However, what Park Wunggyu

focused on in Nine Pieces of the Dummy was not its

philosophical content per se. Rather, he delved into the formality inherent in

the act of dividing the body’s transformation into religiously symbolic stages

and imbuing them with meaning. It is this formal structure itself that

fascinated him and fueled his practice. In Buddhism, the number nine carries

profound symbolic significance; even those unfamiliar with doctrine are often

intuitively aware of its symbolic power. Park immersed himself in this symbolic

underpinning, probing the Buddhist logic behind dividing the body’s dissolution

into nine parts and tracing its dialectical resistance to reach his own work.

The

title Dummy, meaning “shell” or “husk,” encapsulates the

artist’s tendency to borrow and repurpose various formal constructs established

by religion, presenting them in entirely new contexts. This series is

especially meaningful in that it reflects Park’s deeper inquiry into how the

formal aspects—such as structure, shape, and composition—he consistently works

with might intersect with the act of drawing. In Nine Pieces of the

Dummy, the bodily transformation is largely expressed through shifts

in form and texture. To Park, this resembled the expressive possibilities of

painting itself. The gradual crumbling and drying of the human body, as

depicted in Nine Pieces of the Dummy, paralleled the

artist’s own handling of paper, ink, and water—media central to his practice.

Human

beings are, in truth, inscrutable creatures. They are capable of killing

because of the sun, or feeling no sorrow over their own mother’s death. Through

Meursault in The Stranger, Camus had already pointed out

that humans are not inherently noble beings simply because they attach grand

meanings to their own actions. The human figure (or once-human figure) that

Park Wunggyu extracted from Nine Pieces of the Dummy

strongly resembles Camus’ Meursault. In his works, people are not necessarily

subjects of unconditional reverence; rather, they exist simply and plainly as

objects. In Park’s paintings, subjects, images, and voids each simply “exist,”

seemingly wrapped in a barricade that resists interpretation, suggesting that

art—his art, in particular—need not be as profoundly significant as the

meanings people impose upon it.

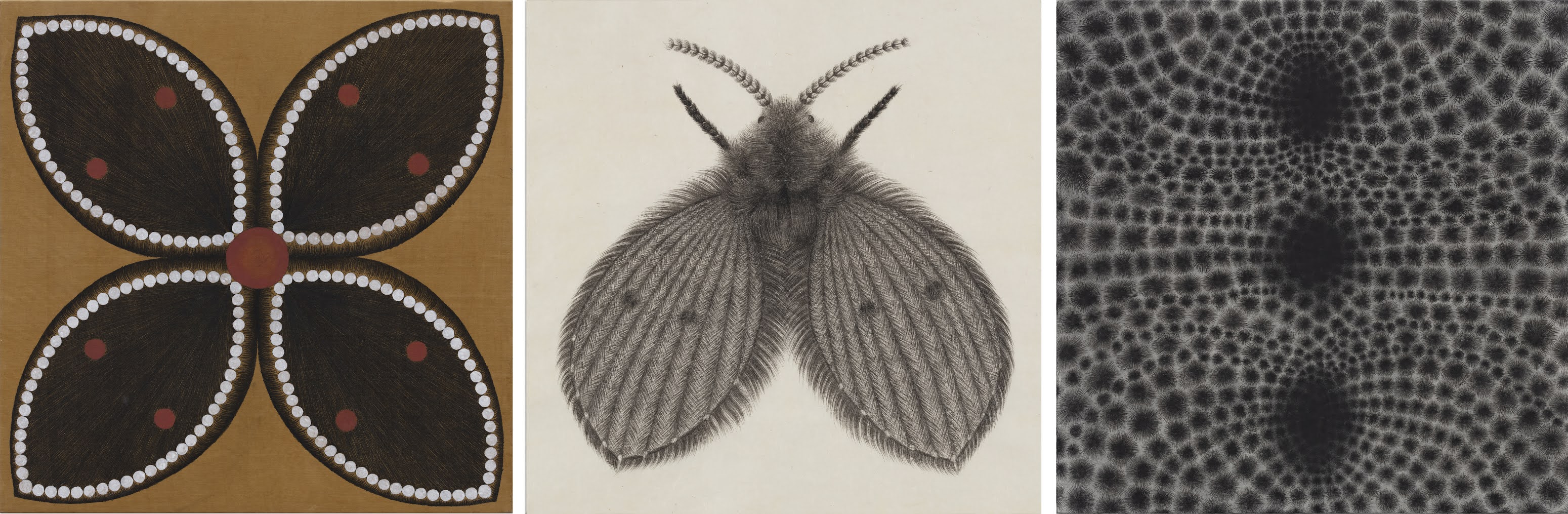

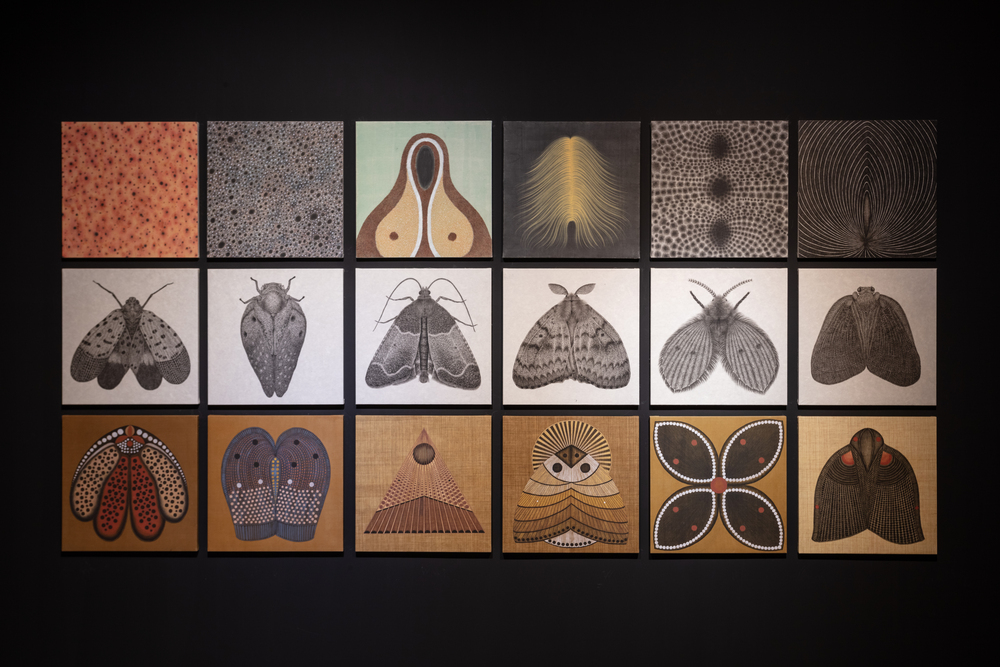

First

launched in 2015, the ‘Dummy’ series began somewhat incidentally. Depicting

grotesque forms of insects or plants, and revulsive imagery such as skin

diseases in the manner of religious iconography, the series stemmed from a

childhood memory. Growing up in a house filled with Catholic objects, Park did

not find comfort in them; rather, they seemed repetitive, compulsive, and even

frightening. One day, upon encountering the corpse of a dead insect, he was

struck by the symmetrical, intricately segmented structure of its body. Though

repulsed, the form also reminded him of religious iconography. From then on, he

began to depict peculiar structures and forms discovered in insects using

mythological or religious visual languages. While he had previously worked with

themes of disgust, filth, and negation, it was with this series that he felt,

for the first time, a desire to continue creating a sustained body of work.

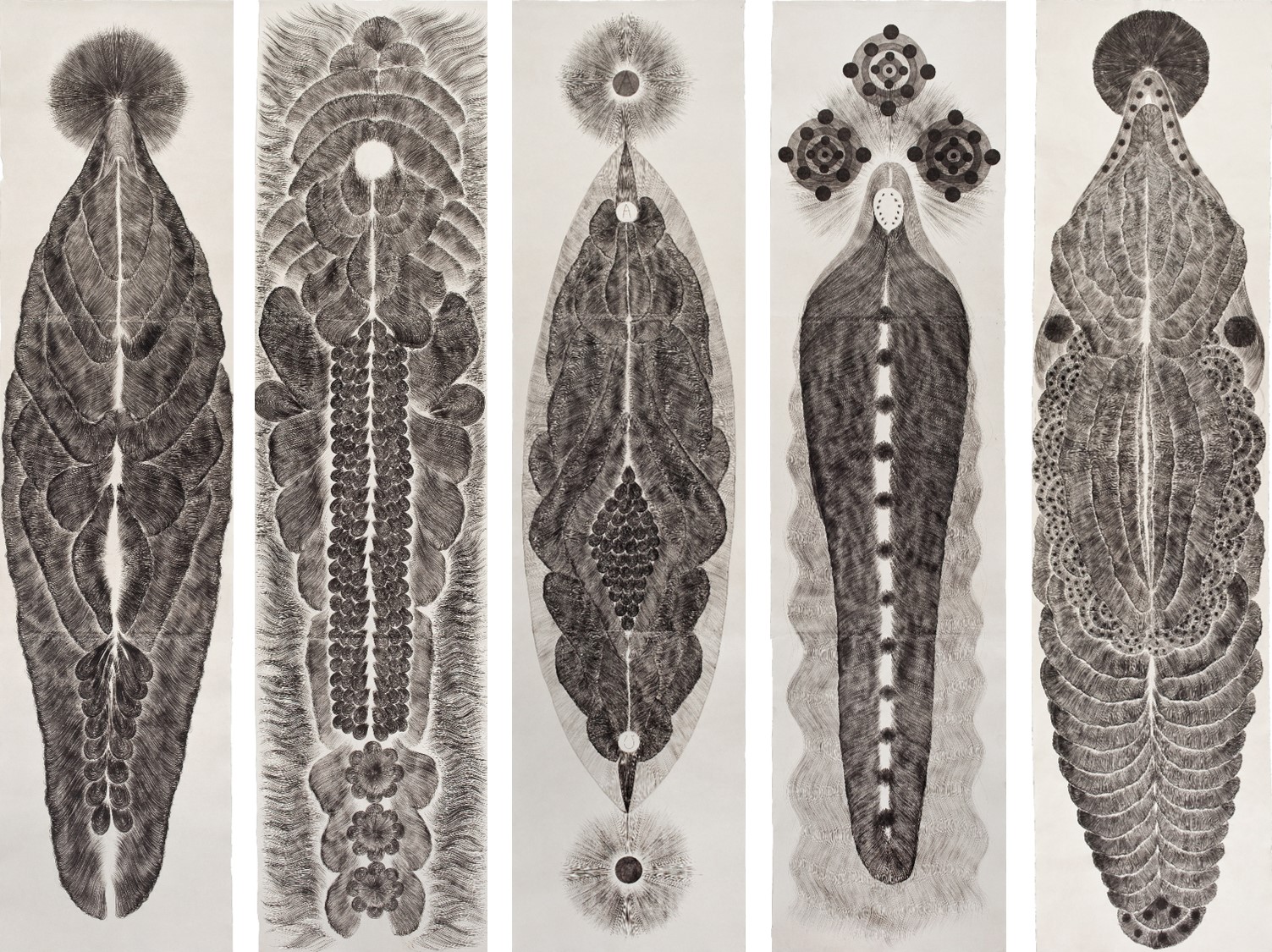

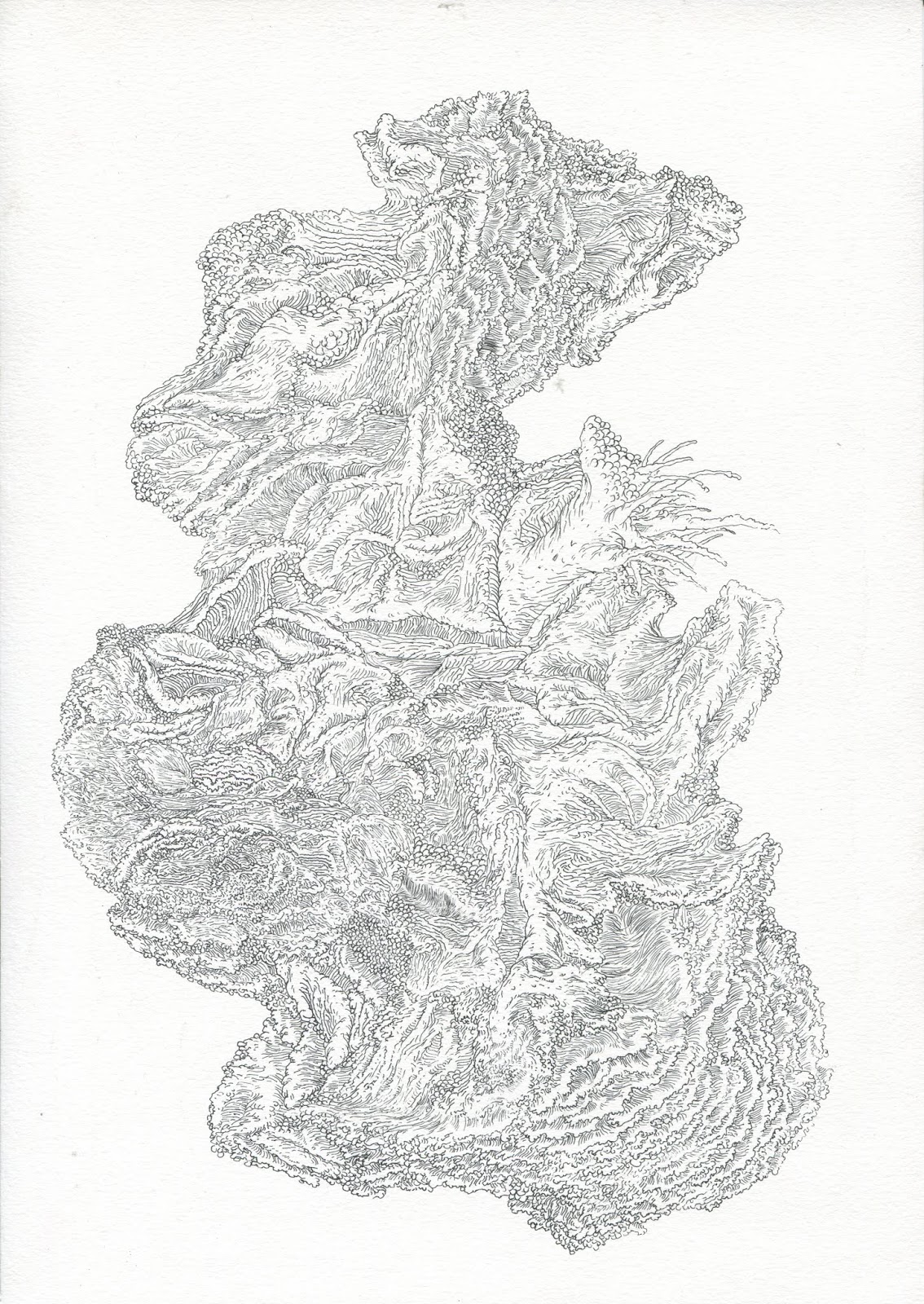

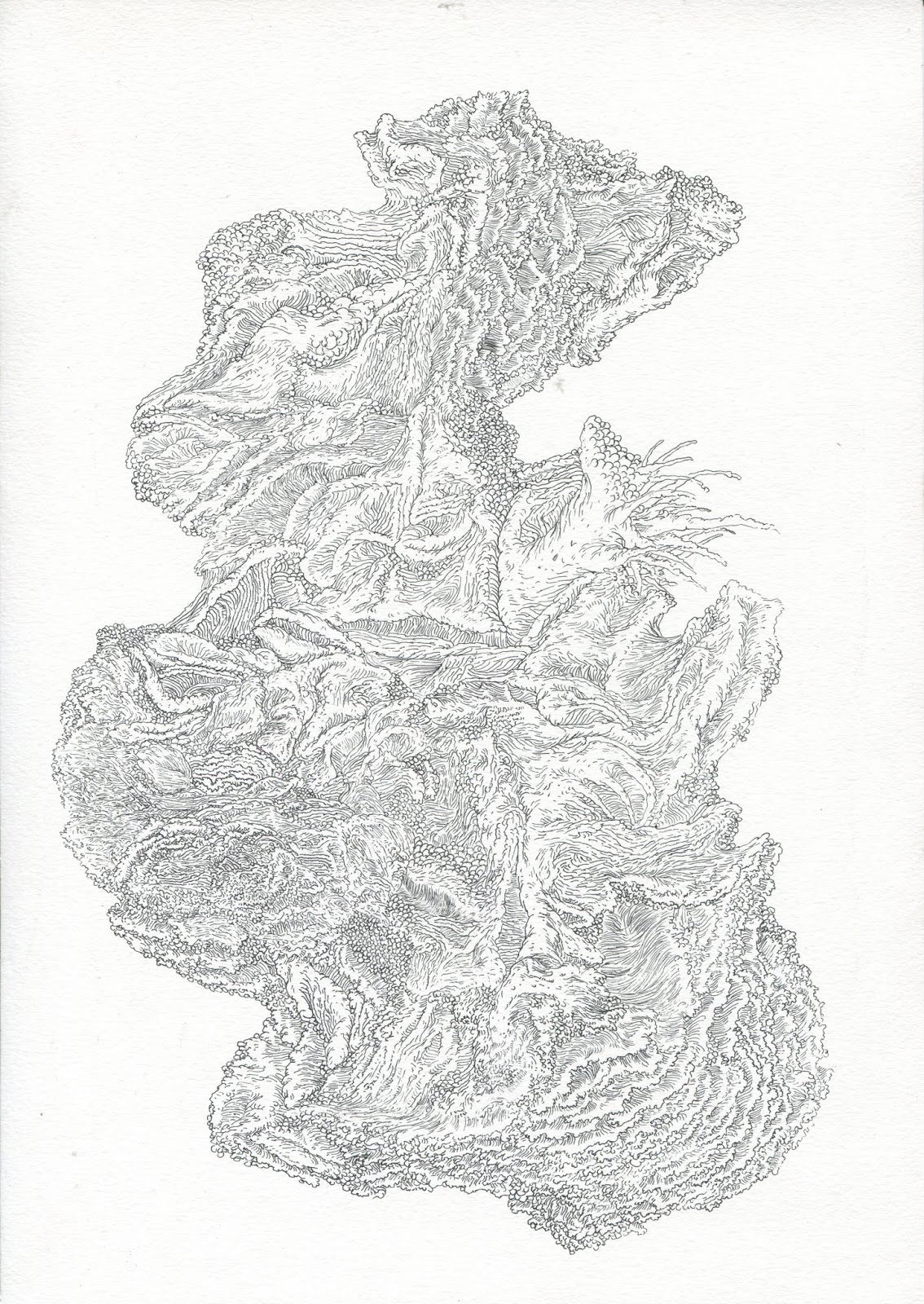

Through

his ongoing exploration of Dummy, Park came to realize that

the framework of his expressions had become somewhat codified. With his recent

works, he has begun to concretize his drawing methodology. His aim, however, is

not merely to perfect a mechanical technique, but rather to develop a painterly

style. In this endeavor, Park builds upon the classic painterly notion that the

texture of a medium determines the character of a form, and that content gives

rise to form—setting a foundation on which to mature his practice.

Park’s

practice is closely intertwined with religion. While it is not directly tied to

the doctrine of any particular faith—nor is it meant to imitate one—his work

often employs religious language and form. At times, he even adapts and

critiques religion through altered content, making it impossible to claim that

his work is entirely unrelated. He overlays the image of the “sacred” onto the

skeleton of the “impure,” and, conversely, cloaks the “sacred” in the skin of

the “impure.” Constantly weighing the two within his work, Park paints with a

meticulous and obsessive hand, as though performing a devotional rite. This

attitude functions as both a mechanism for neutralizing the uneasy pleasure of

depicting the impure and as a stylistic approach that is itself rooted in

impurity.

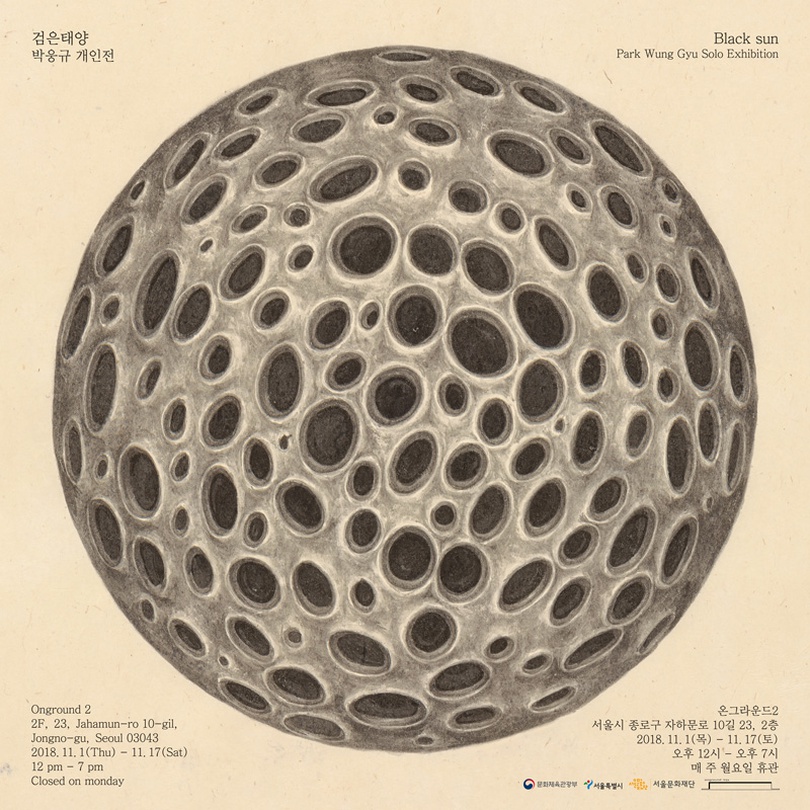

In

many religious practices, pain and hardship are endured repeatedly—often

voluntarily—as acts of penance, eventually leading to spiritual salvation or

catharsis. Park sees this mode of religious self-discipline as deeply

unhealthy, even perverse. This sensibility extends not only to the imagery of

his work but also to its textures. The materials he uses—hanji (traditional

Korean paper) and ink—respond differently depending on repetition, transforming

into completely distinct substances. With each brushstroke, the surface retains

a mark. Unlike canvas, where material remains intact, the paper wears down with

each stroke. The ink, soaking into the damaged fibers, produces a texture that

no other surface can replicate. Paradoxically, the more the paper deteriorates,

the deeper and richer the ink appears—a contradiction the artist deliberately

embraces.

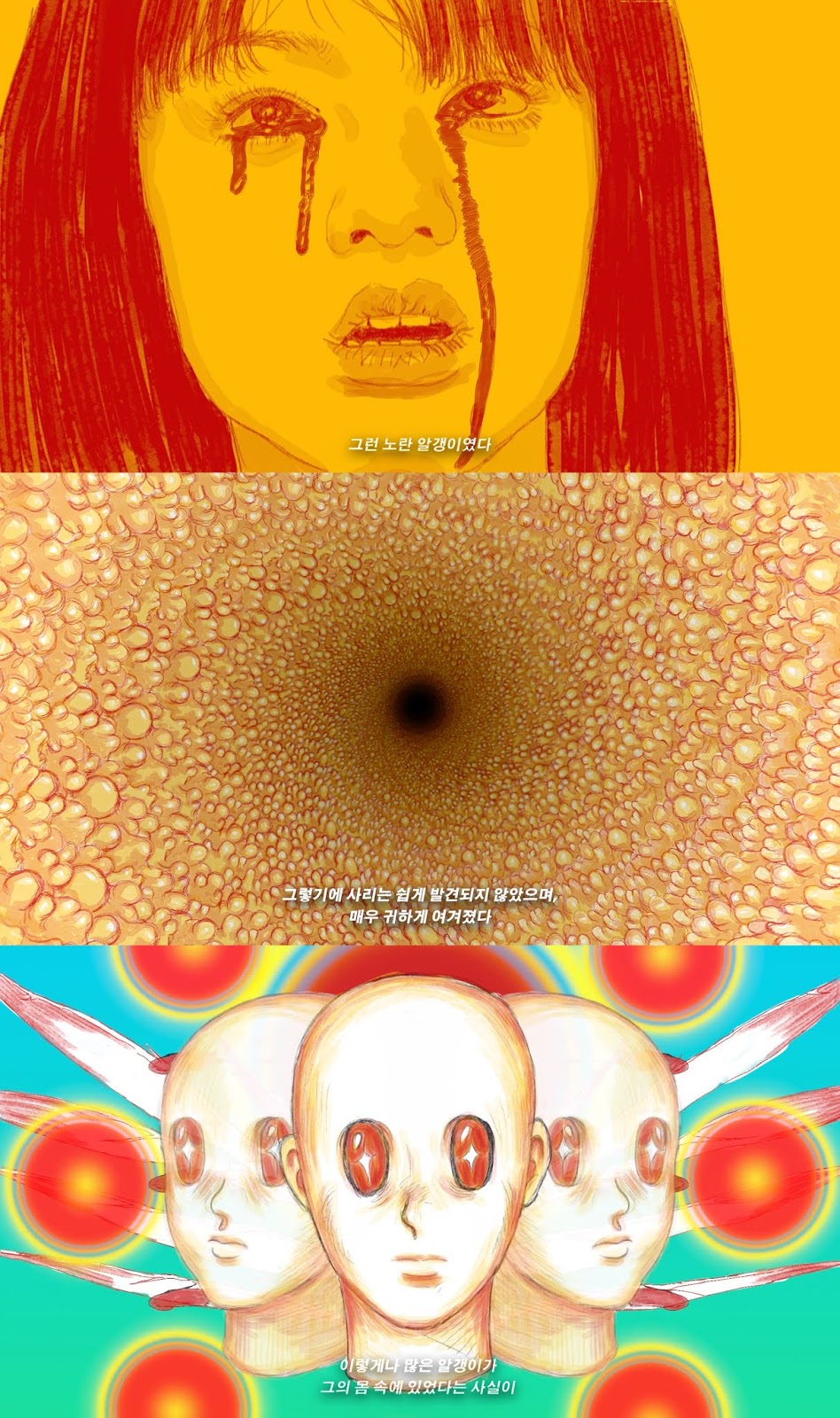

Just

as he once condensed primal, filthy, and erotic instincts into his 2016 video

work Sputum Creed, Park Wunggyu constructs his narratives

with either extreme precision or hazy concealment. Whether it’s the ongoing 〈Dummy〉 series, the Sputum series, or

entirely unpublished works, they are all rooted in a single consistent

framework. Though differing in medium and subject matter, each is a struggle

born from the same source—a set of allegories to which the artist has been hyper-attuned

since childhood. Sputum Creed also reveals how the artist

views images from popular culture as part of a dual attitude toward

“negativity,” further affirming the consistency and urgency of his artistic

perspective.

Rather

than engaging in broad, superficial discourse or issuing overt social

commentary, Park Wunggyu’s work speaks to the emotional core that lies deep

within the individual—a bullseye of private sensibilities. His practice is

solemn, like that of a warrior sharpening the tip of an arrow. Still, he

constantly overturns and questions how the themes in his work reflect or speak

to contemporary society. He insists that what his work ultimately handles is no

more than a shell, and that we are far from free of the illusions cast by such

shells.

Even

those who seem cold-blooded and emotionally numb likely harbor a utopia deep

within. Art plays the role of channeling this inner utopia into the real world,

allowing it to be shared with others. Viewers wander among the imagined

constructions Park has reassembled, encountering radiant fragments of thought

shaped in the depths of human interiority. For those trudging through dull,

mechanical daily lives, art becomes an oasis. Park Wunggyu’s work, too, offers

such respite. His pieces, which poignantly and sublimely depict what was once

too impure to reveal, serve as elegant surrogates for our hidden thoughts.

So

perhaps it’s best to simply enjoy the strange harmonies he has created and

leave the arduous task of decoding his intricate intentions for another time.

After all, we’re not obliged to be responsible for everything.