Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

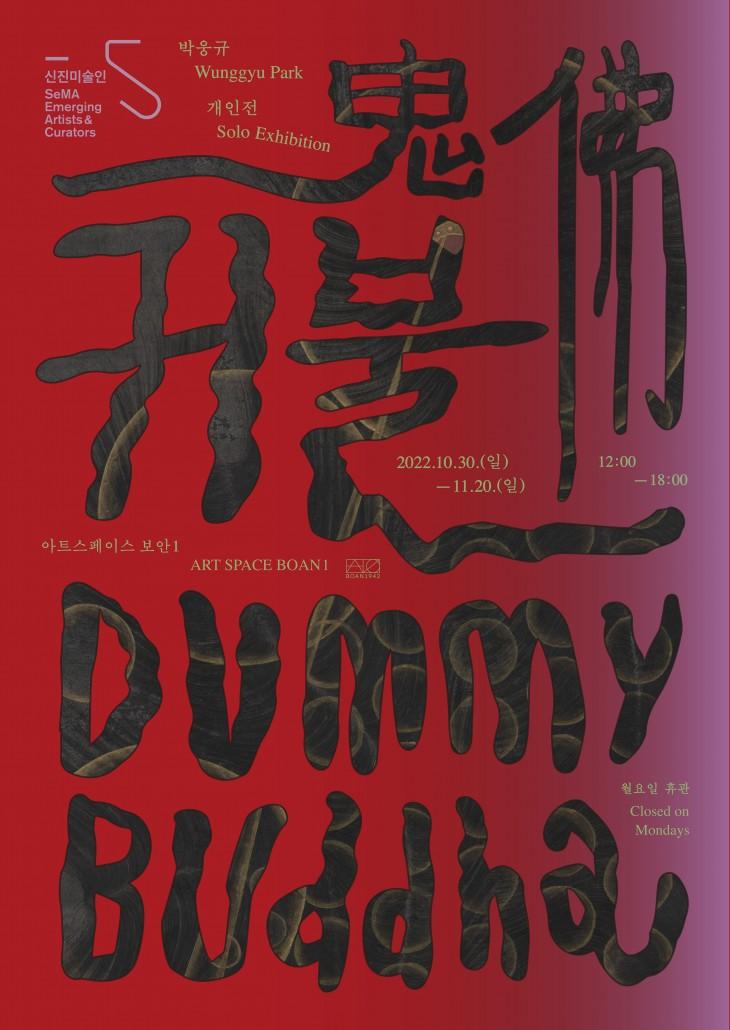

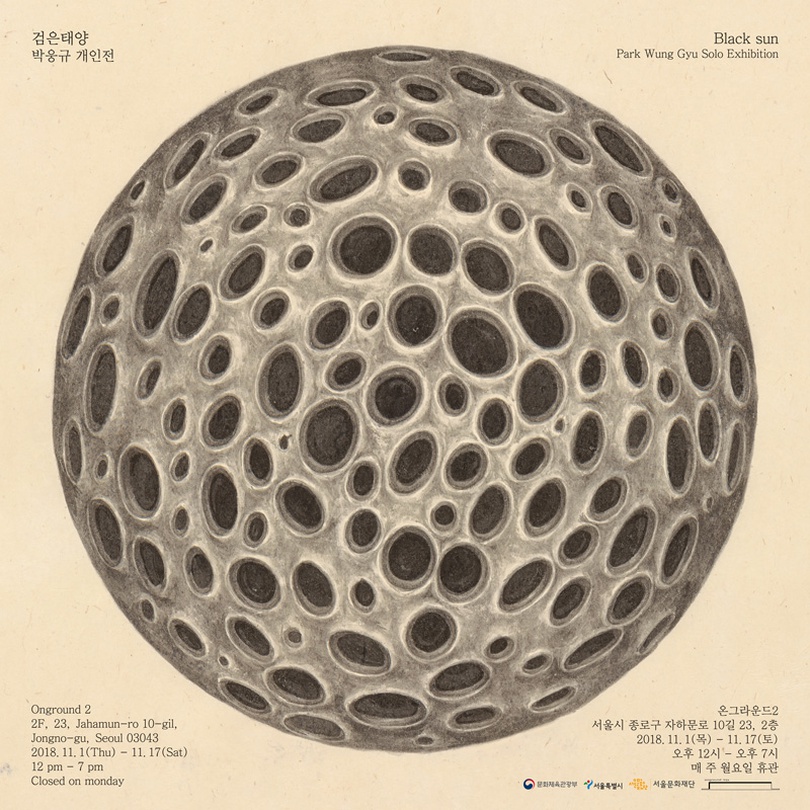

Park Wunggyu has held solo exhibitions at

various institutions such as ARARIO GALLERY SEOUL (Seoul, 2023), Art Space

Boan1(Seoul, 2022), Onground2 (Seoul, 2018), and Space Kneet (Seoul, 2017), and

Cheongju Art Studio (Cheongju, Korea, 2016).

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

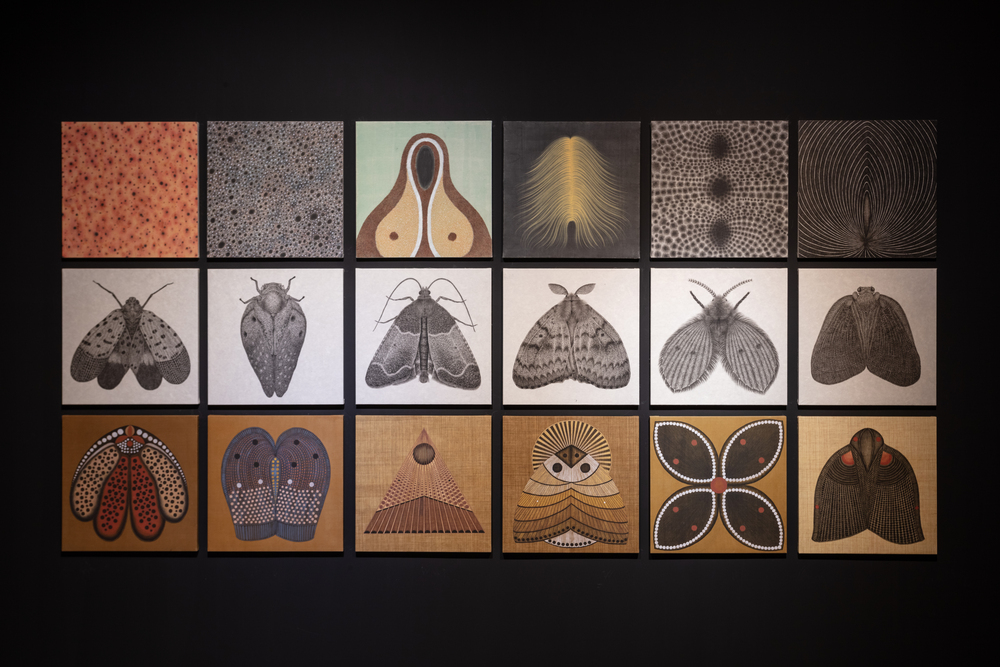

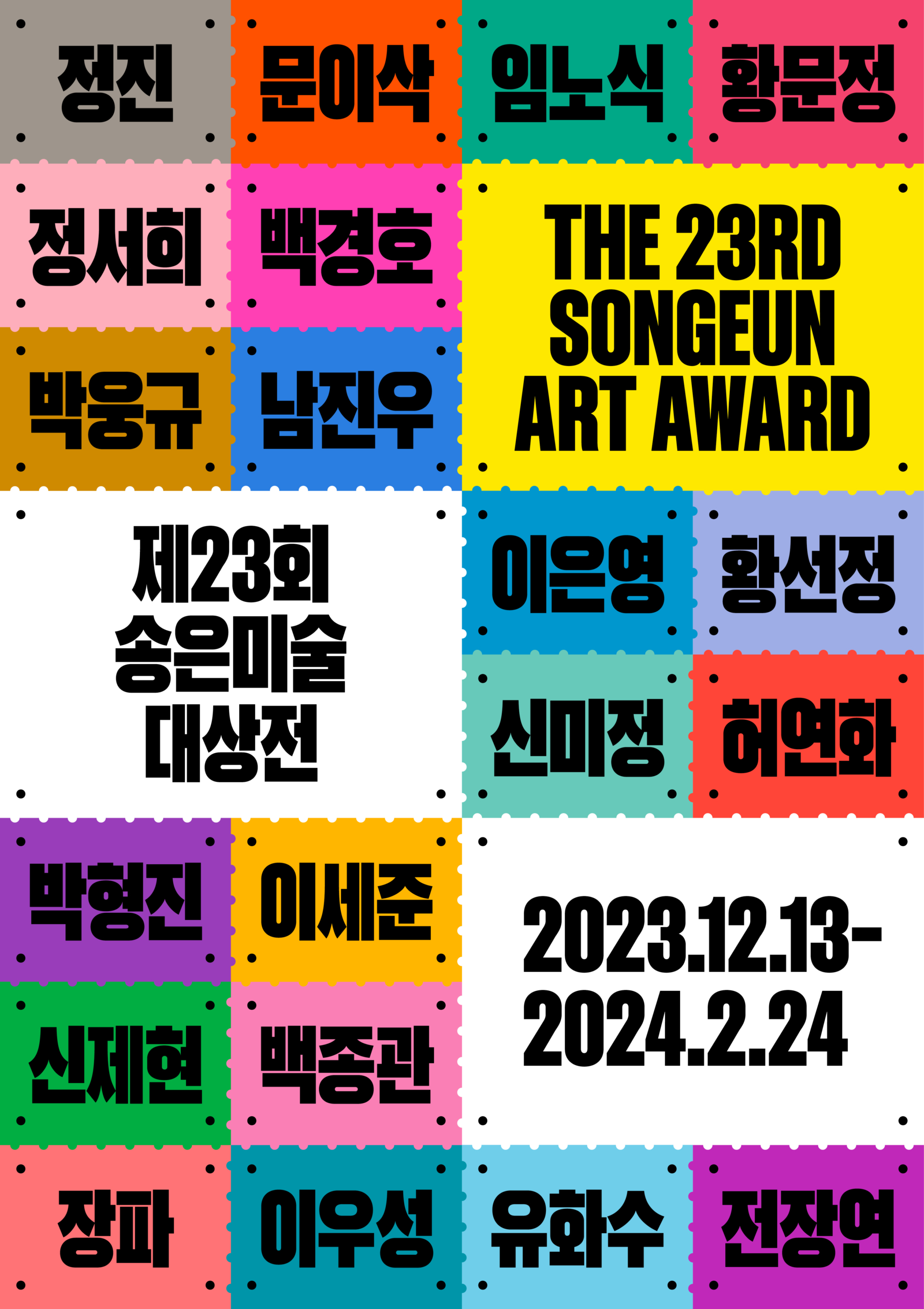

He has

also participated in various group exhibitions held at Chamber (Seoul, 2024),

SONGEUN (Seoul, 2023), Museum of Contemporary Art Busan (Busan, Korea, 2023),

Ilmin Museum of Art (Seoul, 2023), Seoul Museum of Art (Seoul, 2022), Danwon

Art Museum (Ansan, Korea, 2021), Art Sonje Center (Seoul, 2021), Aram Art

Museum (Goyang, Korea, 2019), and more.

Awards (Selected)

In 2024, He was selected as one of ‘the 13th

Chong Kun Dang Arts Awards Artists of the Year.’

Residencies (Selected)

Park Woong-gyu was selected as an artist-in-residence at the Cheongju Art Studio in 2016.

Collections (Selected)

His works are part of the collections at institutions including the Seoul Museum of Art, Museum of Contemporary Art Busan and ARARIO MUSEUM in Korea.