1. A Discovery in Tongyeong

While walking along the Dyemigi coast in Tongyeong, Ahnlee Lee (hereafter

“Ahnlee”) stumbles upon a fragment of peeling paint shed from the surface of a

ship. It was a remnant of marine coating—a form of painting in its own right.

The purpose of such coating is well known: to prevent salt-induced corrosion of

metal hulls. This process is vital for extending a vessel’s lifespan, requiring

multiple layers of paint to ensure durability. Yet beyond structural

protection, the coating contributes to the vessel’s resistance against seawater

and shifting air conditions, ultimately affecting the internal environment

aboard—a fascinating intersection of utility and atmosphere.

Why, then, did Ahnlee pick up

this weathered scrap of paint? Influenced heavily by classical painting, Ahnlee

regards painting as a poetic act of discovering beauty. Yet rather than

reproducing form or rendering imagery, his work leans toward shaping emotion—his

paintings do not depict appearances or even inner visions so much as they

attempt to form a particular emotional texture. Perhaps this is why Ahnlee’s

paintings appear more concerned with the skin or surface of things. Skin, the

body’s largest organ, breathes and exhales, regulating internal and external

states—not unlike the role of marine coating.

The ship’s paint fragment, though

a kind of makeup designed to endure long voyages, was not merely cosmetic. Once

shed, like flaked skin, it still retains its function: it protected what was

beneath. These discarded shells can be seen as abjects—remnants that once

served a purpose but are now cast off. Can a painting rooted in function

transcend into something beyond? Ahnlee carefully collects these abjects as if

searching for future possibilities in painting. He spends most of his time

among plants. The word “greenhouse” stems from the idea of a nursery—a space of

healing. In this space, where the living and the dead, the biological and the

inanimate, coexist in their own order, Ahnlee acknowledges the unique value of

each.

2. Ahnlee’s Summer

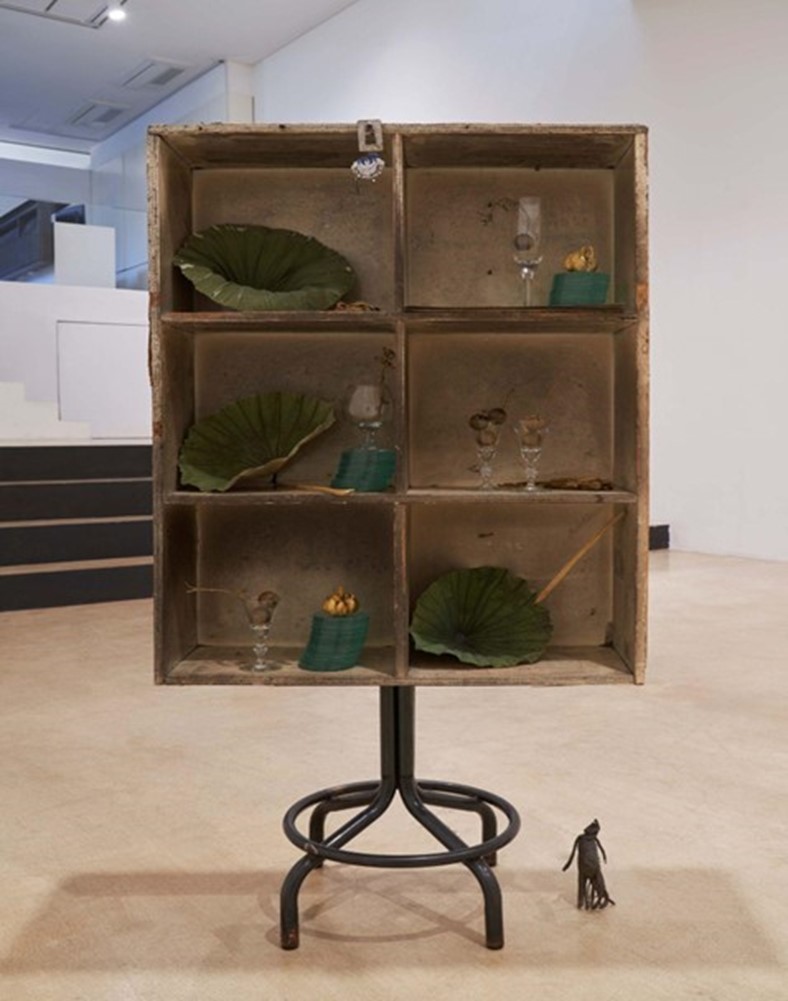

For a long time, Ahnlee has experimented with multidisciplinary projects.

Rather than focusing on a single medium, he thrives in layering space, objects,

people, and actions—allowing unpredictable situations to unfold. This current

exhibition begins with a book. Upon reading Shakespeare’s A Midsummer

Night’s Dream, Ahnlee draws a connection between a serendipitous

summer night and painting. In the play, he finds a character akin to the

peeling paint he discovered in Tongyeong: Puck.

Without Puck, the chaos of

midsummer—love, conflict, mischief, and misunderstanding—would not exist.

Descended from the lineage of fairies, Puck interferes in human affairs,

causing confusion and laughter, not out of malice but playful meddling. Neither

fully human nor divine, Puck invokes chance to trigger pivotal moments, all

while remaining endearingly mischievous. In many ways, Ahnlee mirrors Puck’s

nature. Like Cupid, Puck misfires his arrows, disrupting fates with mistaken

desires and jealousy. Yet the characters in the play accept the unraveling of

order under the generous spell of midsummer night, allowing buried desires to

surface.

Could painting at night be a

space-time where all things desired—outside convention—can finally be accessed?

In his nocturnal paintings, Ahnlee stains the canvas with marks that resemble

nectar blooms, as if each figure secretly gazes at another. Like Puck, he

tiptoes through relationships, gently stirring new situations into being. In

the dream of a summer night, Ahnlee worships darkness with anthraquinone blue—a

pigment like oxidizing sparks, flickering and dissolving in the heat of the

night.

3. Dwelling with Plants

After years of living in transit, Ahnlee Lee now finds himself anchored—perhaps

by fate—through his encounter with plants. Though it remains uncertain how long

this settled state will last, this moment seems to mark a period in which the

many fragmented memories of his past quietly begin to germinate within his

painting. The fervent ambitions he once launched toward the stars now descend,

like Prometheus, into the vital world of the earth. The constellations, once

unreachable, now bathe the soil and guide him into a realm of flourishing life.

Through plants, Ahnlee senses the

boundless vitality of the earth. The plants seem to whisper that it is time for

him to dwell. And so, he becomes a caretaker of nature. In his eyes, nature is

vast—it encompasses not only flora and fauna but also family, acquaintances,

objects, and memories: all forms of human and non-human existence. Yet among

these, it is flowers that he holds with particular tenderness. For Ahnlee, the

flower is a being of reciprocal care. It is through this relational

dynamic—where artist and flower mutually tend to one another—that his work

gains depth.

He pays close attention to the

flower’s anatomy: stamen, pollen sac, ovary, stigma, and pistil. These organs

serve as more than botanical elements; they open a threshold to other

perceptual worlds. Ahnlee is drawn to this primordial imagination—an elemental

world evoked by the mucous membrane of a stigma or the pollen-bearing filament

of a stamen. Thus, he invites us to imagine the flower not as an objectified

symbol of beauty, but as a structure of living form—a site where perception,

sensation, and life converge.

4. Nocturnal Painting

Ahnlee has long pursued a practice of experimentation—often formless and

performative in nature. His projects at Apricot Bar in Seongbuk-dong were

shaped by the interplay between life and the things around him. In this strange

realm—neither here nor there—he assumed the role of an alchemist, transforming

the insignificant into something precious. For years, he drifted between ideals

and reality, navigating both the brink of success and the edge of despair. Yet

these periods of wandering were not wasted—they were, perhaps, the slow

unraveling of brilliance, peeling back layers to approach reality more

intimately.

Through nocturnal painting,

Ahnlee does not simply indulge in the fleeting pleasures of summer night

reverie or grant himself permission for hidden desires. Rather, he extends this

allegory of mischief into a deeper painterly meditation. The dark blues that

dominate his canvases, the rock-like masses, and the foamy, blooming particles

that emerge between them—these are not mere elements of night. This time, he

employs sand as a primary material, as if attempting to pierce into ancient

time. One is reminded of the Navajo sand paintings of New Mexico—rituals of

embodiment and invocation.

In this way, painting becomes a

“response” to the world. The work begins through encounters with nameless

things, with fragments overlooked by others. These sensorial and spontaneous

reactions form the seedbed of his practice. He sifts the grains of sand, fixes

them onto canvas with adhesive, then polishes the surface with sandpaper until

it evolves into a tactile plane. What follows is a phenomenological process of

caressing, kneading, and striking. Ahnlee communicates through the body.

The philosopher Luce Irigaray

describes this type of engagement as “the body and flesh that desire to speak

to the Other” (The Way of Love, trans. Jung Seoyoung,

Dongmunseon, 2009, p.35). These gestures—his gestures—stand as witnesses of the

night. They watch, with a cyclopean gaze, the mischief of Puck and Ahnlee

unfold.

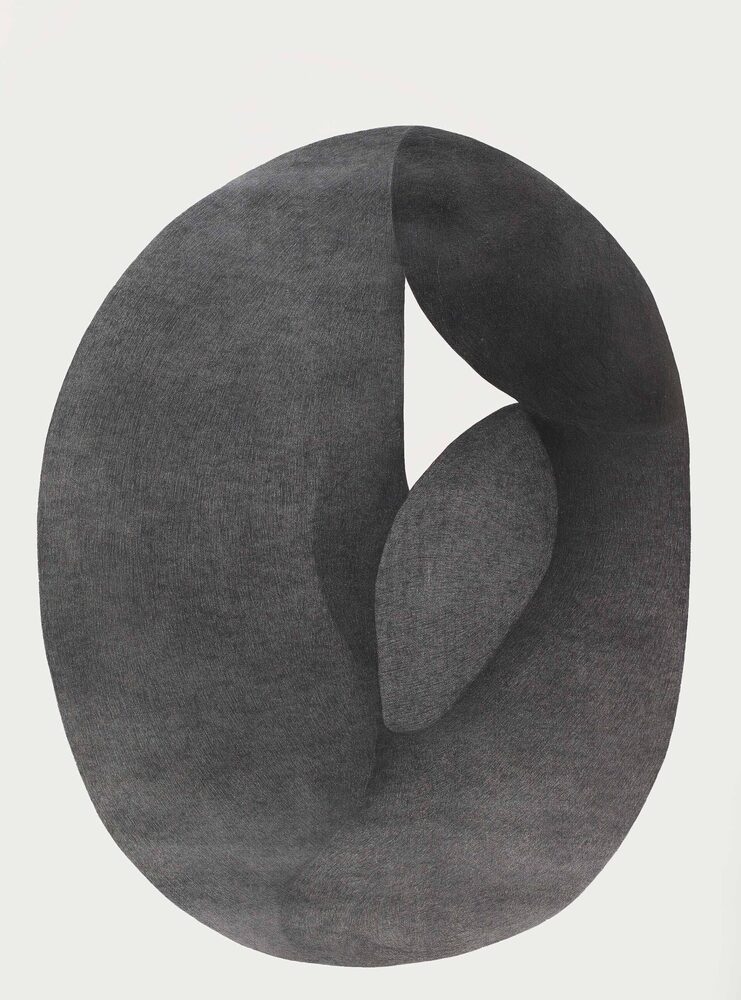

Included in this summer night’s

festival are two earlier works: Depart I (2011) and Depart

II (2016), graphite on paper, which emerge like preludes to the

nocturnal paintings. Here, painting unravels time. Through surrealist traces of

the unconscious, Ahnlee’s canvases bring past and present into collision,

dismantling linear temporality. In this ongoing movement between dwelling and

wandering, he continues to explore the possibility of a vegetative life. This

paradoxical cycle—between rooting and uprooting—may well be the source of all

his work, whether painting, sculpture, object, or gesture.