Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

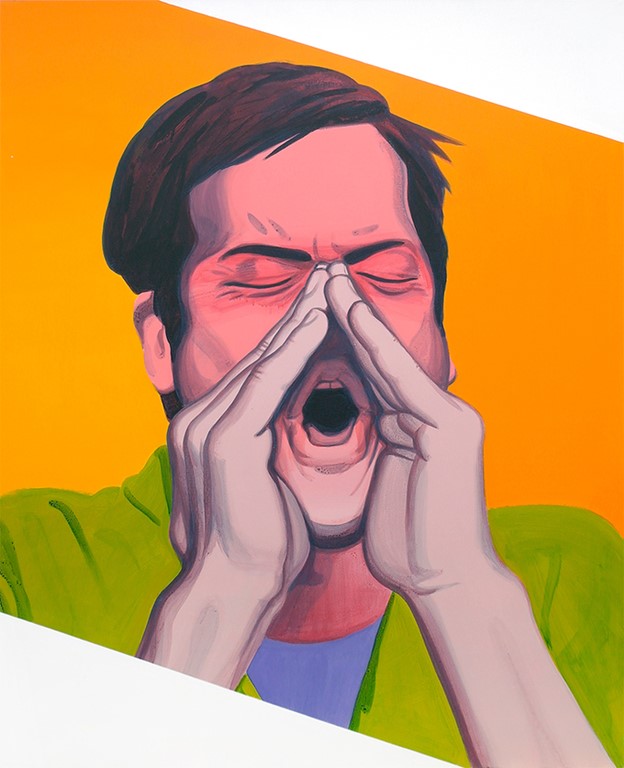

His major solo

exhibitions include 《Come Sit with Me》 (Hakgojae Gallery, Seoul, 2023), 《But some

day, one day, soon》 (DOOSAN Gallery, Seoul, 2021), and 《My Dear》 (Hakgojae Gallery, Seoul, 2017).

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

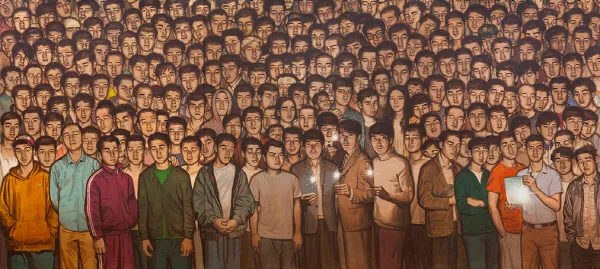

His major

group exhibitions include 《Time Lapse》 (Pace gallery Seoul, 2024), 《Real DMZ Project : Checkpoint》 (Dora

Observatory, Yeongang Gallery, Paju, 2023/ Kunstmuseum of Wolfsburg, Wolfsburg,

Germany, 2022), 《The Society of Individuals》 (Museum of Contemporary Art Busan, Busan, 2021), and Gwangju

Biennale 2018 《Imagined Borders》 (Asia Cultural Center, Gwangju, 2018), The First Jinan

International Biennial 《Harmony-Power》 (Shandong Art Museum, Jinan, China, 2020), 《Follow, Flow, Feed》 (ARKO Art Center, Seoul,

2020), 《Immortality in the Cloud》 (Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul, 2019), among others.

Awards (Selected)

Lee was selected as an artist-in-residence at

the Seoul Art Space Geumcheon (2023), The Physics Room in New Zealand (2016),

SeMA Nanji Residency (2015), Cow House Studio in Ireland (2014), MMCA Residency

Goyang (2013), and more.

Collections (Selected)

The Artist’s works are in the collections of the

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea, Seoul Museum of Art,

Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Cheongju Museum of Art, and more.