In an era where physical contact

with others is heavily stigmatized, Youngjoo Cho’s recent works encapsulate

acts of flesh meeting flesh through video and music. Although they stem from

the same experiential source, the videos convey this contact more directly,

while the music remains somewhat abstract. Reflecting the differences between

these genres, they function complementarily. During the exhibition period,

temporary performances are captured on video and screened, while the

installations themselves serve as stages for the performances. The ancient art

of performance, through musical instruments, is integrated with installations

that also function as instruments. Depending on the context, all of these

elements can be experienced virtually through online tours, demonstrating

fluidity and interchangeability across mediums. By mediating actions through

the body, Cho’s works transform meaning as they traverse different media.

The conceptual genesis of the

series collected under the title 《Cotton Era》 was inspired by the intimate

contact involved in childrearing. Cho meticulously formalizes this primal

experience to prevent it from fading into oblivion. Works featuring intertwined

bodies in physical struggle and musical performances using wind instruments

emphasize the act of breathing. Here, breath symbolizes life, art, and

relationship.

In his book “The Mystery of

My Body; The Greatest Miracle in the World”, physician-author André Giordan

notes that we breathe about 10,000 liters of air daily and take approximately

500,000 breaths before dying. Translated into numerical data, this

physiological fact, which is otherwise too obvious to notice, takes on new meaning.

Giordan argues that our bodies themselves are miracles. If that is the case,

then giving birth to another body and nurturing its survival, at least through

the critical phases of life, must also be a miracle. The process of nurturing a

child inside and outside the mother’s body for an extended period is, in

itself, a transgenerational miracle.

Youngjoo Cho approaches the

burdens and joys of caregiving with an objective, almost scientific distance,

documenting and interpreting them. Just as we rarely think about breathing

unless we experience respiratory distress, caregiving labor, until feminist

discourse highlighted its significance, was regarded as a natural, unquestioned

obligation assigned solely to women.

Unlike animals, human infants

require prolonged protection, granting mothers absolute control over life and

death. This duality of motherhood—both life-giver and potential

life-taker—generates the ambivalent image of mothers as both nurturing and

terrifying. Nancy Chodorow, a psychoanalyst who merged psychoanalysis with

feminist theory, argued in “The Reproduction of Mothering” that an

infant can never be completely independent. Without maternal protection,

infants cannot survive, nor do they experience themselves as separate

individuals. According to Chodorow, the infant’s original relationship with the

mother is driven by self-preservation, and libidinal attachment develops within

this context. Thus, infants feel omnipotent under the care of the mother who

provides everything, leading to a lifelong pattern of selfish love.

The mother-child relationship is

inherently asymmetrical, with the mother representing an absolute, divine other

to the child. Conversely, to the mother, the child is an internalized other or

an extension of herself throughout pregnancy and caregiving.

While feminist sociology has

examined women’s caregiving labor as “shadow labor,” Cho’s approach—connecting

it to the body and breath—offers a more fundamental perspective on motherhood.

In a world where ideological persuasion is difficult, even in feminist

discourse, Cho’s unique approach offers significant insights. 《Cotton Era》 alludes to the natural fibers

used in childcare, materials that clean bodily fluids and protect the body

warmly and softly from the outside world. If these cotton products, which navigate

the boundary between dirt and cleanliness, could symbolize commodity

fetishism’s unique sexuality, who else but women would best embody that

symbolism?

The act of wiping away bodily

fluids inherently traverses the duality of dirt and cleanliness. The cotton

products that touch a child’s skin, forming the boundary between mother and

child, are as sensitive as the title of Cho’s video work, Feathers

on Lips. The artist translates this delicate sensitivity into larger,

more dynamic actions reminiscent of sports or dance.

In Feathers on Lips,

the meticulously calculated movements of the bodies resemble athletic

competitions or choreographed dances. Yet, the imagery of bodies clashing, with

diverse physiques and atmospheres, carries an ambiguous undertone. The actions

range from maternal bonding to homoerotic interactions, from caresses to

violence, creating a discomforting ambiguity for the viewer. According to

psychoanalytic tradition, as discussed in “The Reproduction of Mothering” by

Nancy Chodorow, children’s sexuality is initially bisexual before eventually

forming a heterosexual orientation.

Chodorow critiques the patriarchal

limitations of psychoanalysis by introducing a stage preceding bisexuality,

which she describes as gynesexual or matrisexual orientation. Feminist

theorists like Julia Kristeva emphasize the primal relationship between child

and mother. Women perform relationality even with the beings inside their

wombs, which is why Kristeva considers women not as isolated subjects but as

“subjects in process.” This ambiguous subjectivity plays a crucial role not

only in nurturing but also in artistic creation.

Sexuality is anchored in specific

erogenous zones, but these zones also serve as conduits for aggressive

impulses. Psychoanalysis posits that love and hate share a common origin.

In “Subjectivity and Otherness: A Philosophical Reading of Lacan”, Lorenzo

Chiesa explains that when one sees an idealized image of oneself in the Other,

it simultaneously invokes love and hatred, revealing the unity of narcissism

and aggression. This duality is also evident in masochism and sadism. Chiesa

cites Lacan’s concept of “love-hate” to argue that aggression underlies

altruism, idealism, education, and even activism. In this context, the

avant-garde is a prominent example, and artists are no exception. Although

Roland Barthes argued in his semiotic analysis of wrestling that reality is

irrelevant, Youngjoo Cho’s work contrasts this by depicting interactions

between bodies of the same gender, thus evoking ambiguous sexuality and

minority sexual identities that society is reluctant to acknowledge.

Dominant social norms classify

ambiguity in sexual roles and diffuse bodily eroticism as regression or

perversion. Yet the same society that glorifies maternal care also imposes an

ambiguous role on the caregiver, who must navigate the blurred boundaries

between subject and object. Youngjoo Cho’s work does not merely depict the pain

of caregiving; it also explores the joy embedded within it. Beyond pregnancy

and childbirth, maternal caregiving itself is an all-consuming battle that

defies clear boundaries. Cho finds a parallel between childrearing and

art-making; both are total endeavors that demand the full engagement of body,

mind, and spirit. Yet in an era where totality is impossible, the demand for it

becomes an existential burden. Nevertheless, overcoming this burden transforms

pain into pleasure. Like the dialectic of love and hate, pain and pleasure

emerge from the same source. Whether children or art, they are extensions of

oneself, yet they inevitably follow their own paths.

The work Three

Breaths similarly explores boundary-breaking ambivalence. Like

the musical experiments of John Cage and Nam June Paik, Cho’s piece

incorporates dissonance and silence alongside melodic and harmonic elements.

This disruption of conventional musical expectations contributes to its

enigmatic atmosphere, aligning with contemporary music’s aesthetic of

dissonance. The introduction of foreign elements disrupts automatic habits, not

merely for the sake of disruption but to generate new meaning within the

resulting gaps. Breathing is a vital process for sustaining life, yet few

organisms are exempt from the labor required to support it. This labor often

manifests as a sigh, and in an uncanny act of imitation, the child learns to

sigh by mimicking the mother. This mimicry is not merely natural but a form of

socialization, a process by which the child becomes a social being. In the

intersection of linguistics and psychoanalysis, it is argued that one becomes

human through language, a process laden with repression and division.

The pandemic era, which has

profoundly impacted performing arts, serves as a relevant backdrop for Cho’s

work, as it deals with the primal bond between mother and child—a relationship

fundamental to human reproduction that cannot exist without intimate contact.

The intimate connections that enabled childbirth and caregiving have become so

precarious that they may one day be mere memories of humanity. We now

experience this uncertainty not as an abstract idea but viscerally, in our

bodies, as our physical spaces and daily routines shift with every new policy

update. In this era of hyper-surveillance, nature no longer appears merely as

itself. Cho’s work, grounded in the experience of childrearing, examines the

deep-seated cultural beliefs surrounding motherhood, which have remained

stagnant compared to other social domains. Since the advent of modernity, which

sharply divided the public and private spheres, men have remained third-party

observers of these issues, encountering similar experiences only through artistic

creation.

As society moves beyond an era

where women's "works" were confined to childbirth and child-rearing,

a new, uncharted territory has emerged. This realm is surfacing through the

experiences of women artists who endure the duality of pain and joy. Motherhood

is no longer merely an external construct but an internalized exploration. The

perceived "naturalness" of motherhood has long been a patriarchal

ideology. Some may wish to preserve this "purity" forever. However,

the emergence of women as mothers and artists symbolically transforms this

notion of "nature" into a subject of discourse. Discomforting and

nuanced truths, once veiled under the guise of nature, are now being brought

into the realm of dialogue. Youngjoo Cho’s approach to discussing the

unspeakable pain and joy of childbirth and motherhood avoids sentimentality and

revelation. Her work, while not strictly formalistic, maintains an artistic

detachment that is rigorously upheld. The more sensitive the subject matter,

the more disciplined the approach required. She consciously rejects the

sentimental portrayal of motherhood, treating it with experimental detachment.

Her observation of her own experiences is grounded in division, much like the

linguistic approach to dealing with objects.

The single-channel video Feathers

on Lips, approximately ten minutes long, metaphorically portrays

intimate physical contact between bodies. It features interactions between

trained performers/dancers and ordinary people with varying physiques and

demeanors, highlighting physical closeness. The stark white background focuses

attention solely on the two figures, breathlessly intertwined in action. Cho

draws inspiration from wrestling, employing twisting and pressing movements

choreographed through extensive workshops with the participants. The ambiguous

gestures—simultaneously violent and erotic—suggest the close relationship

between the two, blurring the lines between aggression and affection. Violence

and love are alike in their intrusion upon the other’s boundaries, causing

rupture and merging. This complex interplay reflects the human social

condition, where maintaining one's identity requires constant negotiation with

the other.

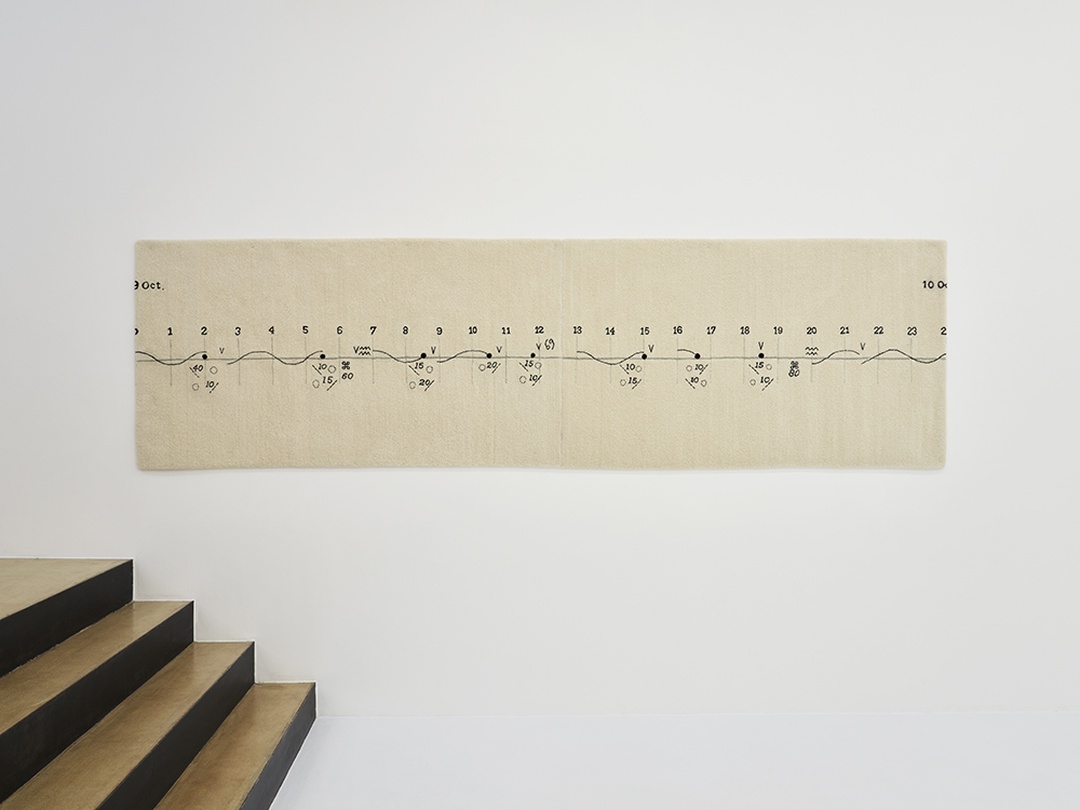

The sound installation Three

Breaths, approximately twelve minutes long, features performers

positioned inside and around serpentine metal ducts resembling giant anacondas.

The composition, centered on wind instruments that emphasize breath control,

includes sighs essential for sustaining life. This piece is based on Cho’s

parenting diary, a continuous record reflecting the unrelenting demands of

caregiving, which defies categorization into neat codes. The score transforms

daily logs into musical notes, leading to a performance centered around breath.

Like her choreographic work, this piece required ongoing collaboration with

musicians. The emphasis on communication and sharing transcends objectification

or thematic exploitation, reflecting a consistent element in her practice. For

Cho, narrative matters more than imagery. Years earlier, she collaborated with

women in their fifties to seventies, learning beauty and cosmetic techniques,

conducting therapy and autobiography workshops, and even organizing a choir.

The intricate numerical data

documenting the parenting process, if printed, would span dozens of meters,

reflecting the complexity embedded in the compositional process, which is

partly shaped by the participating musicians. The winding installation, with

its gaping mouth, evokes corporeal reality. The long metal duct, also used as a

percussion instrument, resembles both a wind instrument and the birth canal or

an umbilical cord. It reflects Cho’s childhood memories of living near tunnels

and symbolizes the seemingly endless labor of caregiving. The artist’s late

entry into motherhood coincided with her transition from life abroad to

establishing her artistic career in Korea, resulting in an intense, battle-like

existence. In 2016, she held a solo exhibition just one month after giving

birth, balancing the demands of parenting and earning a living. Although she

has not fully navigated this journey, Cho continues to explore and share

experiences with other women and artists who have undergone similar life changes,

positioning this exploration as a long-term project.

This deeply lived yet mysterious

territory, marked by sacrifice, devotion, and guilt, will remain a fertile

ground for ongoing artistic exploration. If her earlier works on “ajumma” were

satirical yet serious, her recent pieces arise directly from her present

reality, addressing issues that intersect with her own experiences. As a

mother, artist, and woman, she unconsciously sighs, only to witness her

four-year-old child mimicking her. This child, who has acquired language

unusually quickly, imitates and repeats words like “hope” and “wish,” along

with indecipherable onomatopoeic sounds, which are incorporated into the

performance. This interplay of sound, music, breath, and speech signifies the

child's acquisition of language through the voice of the other (the mother).

The signifier precedes the subject. In the psychoanalytic journey of becoming

human through language, repression and division are inevitable, suggesting an

equally challenging future for the daughter who once received unconditional

care.