This exhibition invites reflection on the categories and

possibilities of the artist's treatment of time. The artist does not merely

remain at the level of understanding time but examines the temporal composition

and the interactions within and beyond its multiple boundaries. Ultimately, the

artist consciously reflects on the modes of existence of the self or the world.

Therefore, the English word "mechanics" in the exhibition title not

only indicates the unified, concrete state of time but also implies the

fluidity of the temporal horizon. Yet, as is well known, “time,” as a dimension

of pure existence, is not easily perceived through sensory experience in the

material world. Moreover, since the formalization of time has long depended on

the medium of sound, it has remained a challenge for visual artists.

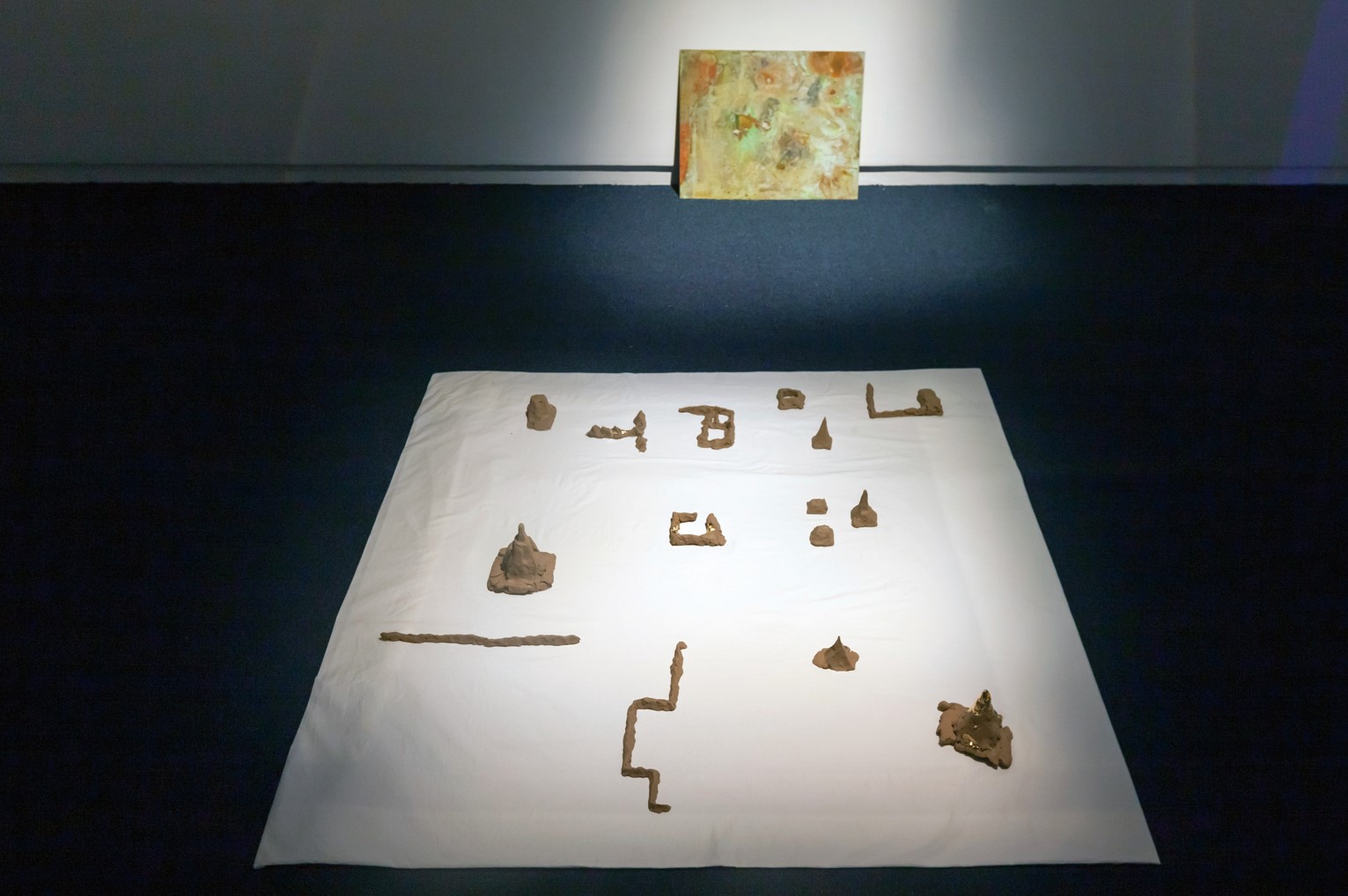

In this exhibition, the diverse media employed by Hwayeon Nam

convey the temporal experiences of life. However, these experiences are not

confined to the realm of the individual but are expanded into social meanings

and spatial dimensions. By involving objects and events in the fleeting

experiences of what has passed, been forgotten, or wished to be recalled, the

works endow these ephemeral moments with an objective materiality. In this

manner, the temporal experience within the material world is recontextualized

as a social form, transforming into a performative aesthetics. This process

leads to the inference of meaning from unrelated objects and events.

The performative actions in this exhibition are expressed through

voice, body, gaze, or as objects themselves, capturing reality. Simultaneously,

the symbolic processes and semantic devices utilized in the temporal media,

where actions are realized, are connected to the spatial movement of the

audience. This connection aims to elevate the artist’s experiential performance

and the viewer’s imaginative participation into a holistic situation. In this

sense, the exhibition showcases a curatorial intention that stands out.

This strategy of organizing time as a unified construct awakens

the conscious and historical presence of the viewer through the artist’s

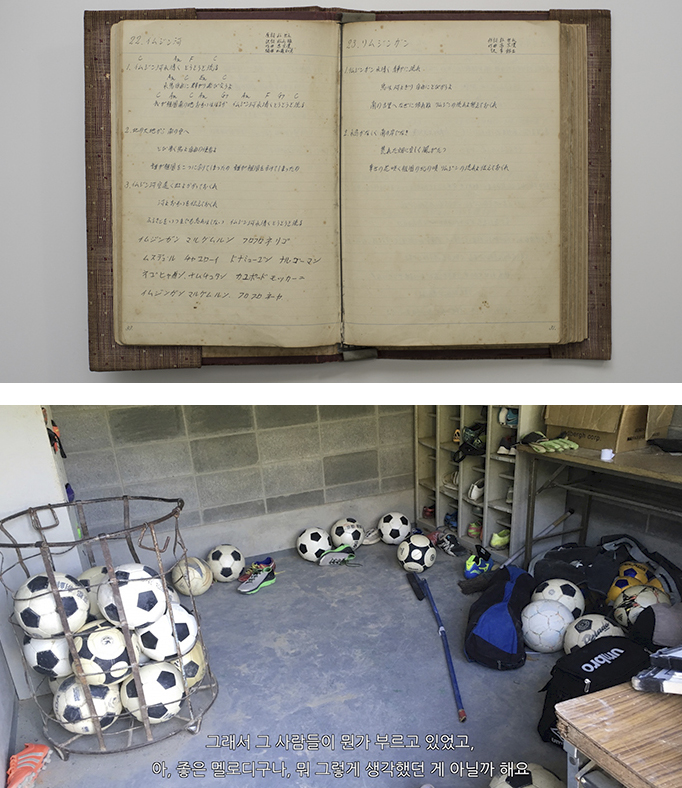

performative actions. In Coreen 109, virtual material

symbols, which substitute for the actual experience of the historical object

“Jikji Simche Yojeol,” emerge, thereby suspending direct engagement with the

past object. Despite the presentation of micro-historical facts, the closer

they approach the present tense, the more our consciousness concentrates on the

visual image of Jikji, believed to reside in a specific space. This cultural

memory’s attachment to the temporality of materiality reveals its potential to

be repurposed as a political form, as evidenced by its ultimate resting places

in modern knowledge-power constructs like libraries and archives.

Nam's video work indirectly conveys that the fragmented memories

produced during the existence of collected objects can further mythologize

them. The more this happens, the more time accepts the courtship of power,

governing consciousness and historical progression. This theme is also evident

in Ghost Orchid and The Adoration of

the Magi. The collecting practices and authority, functioning as

modes of knowledge-power, maximize and visualize the reliability of fragmented

memories. Consequently, the so-called “imagined communities” that rely on

partially collected images, without knowledge of the whole narrative, become

accustomed to accepting past experiences of others in figurative and

metaphorical forms.

As illustrated by Nam, the image bearing Giotto’s religious

prestige is symbolically appropriated in the scientific world, and the colonial

lists created by 19th-century orchid hunters persist as if they were a

consensual “ritual” in modern society. The persistence of such lists signifies

an ongoing need for deeper insights to penetrate the underlying complexities of

“time mechanics,” just as the videos and sounds in the exhibition space are

intertwined. In this way, the freedom of the artist’s concrete performance can

return to the work itself.