Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

Do Ho Suh began gaining international

recognition in the late 1990s, with solo exhibitions such as 《Do Ho Suh》(1999, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, Korea) and 《Seoul

Home/L.A.》(1999, Korean Cultural Center, Los Angeles,

USA). In the early 2000s, he further established his global presence through solo

exhibitions in major art institutions in New York and London, including 《Do Ho Suh》(2002, Serpentine Gallery, London,

UK) and 《Home in Home》(2012, Leeum,

Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea). These exhibitions contributed to

solidifying his artistic concept of “migratory architecture.”

In the 2010s, he expanded his exploration of

personal memory and architecture through exhibitions such as 《Do Ho Suh:

Passage/s》(2017, Bildmuseet, Umeå, Sweden) and 《Do Ho Suh: Almost Home》(2018, Smithsonian

American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., USA). Notably, 《Do

Ho Suh: 348 West 22nd Street》(2019, Los Angeles County

Museum of Art, Los Angeles, USA) presented a precise recreation of his New York

apartment, resonating widely with audiences.

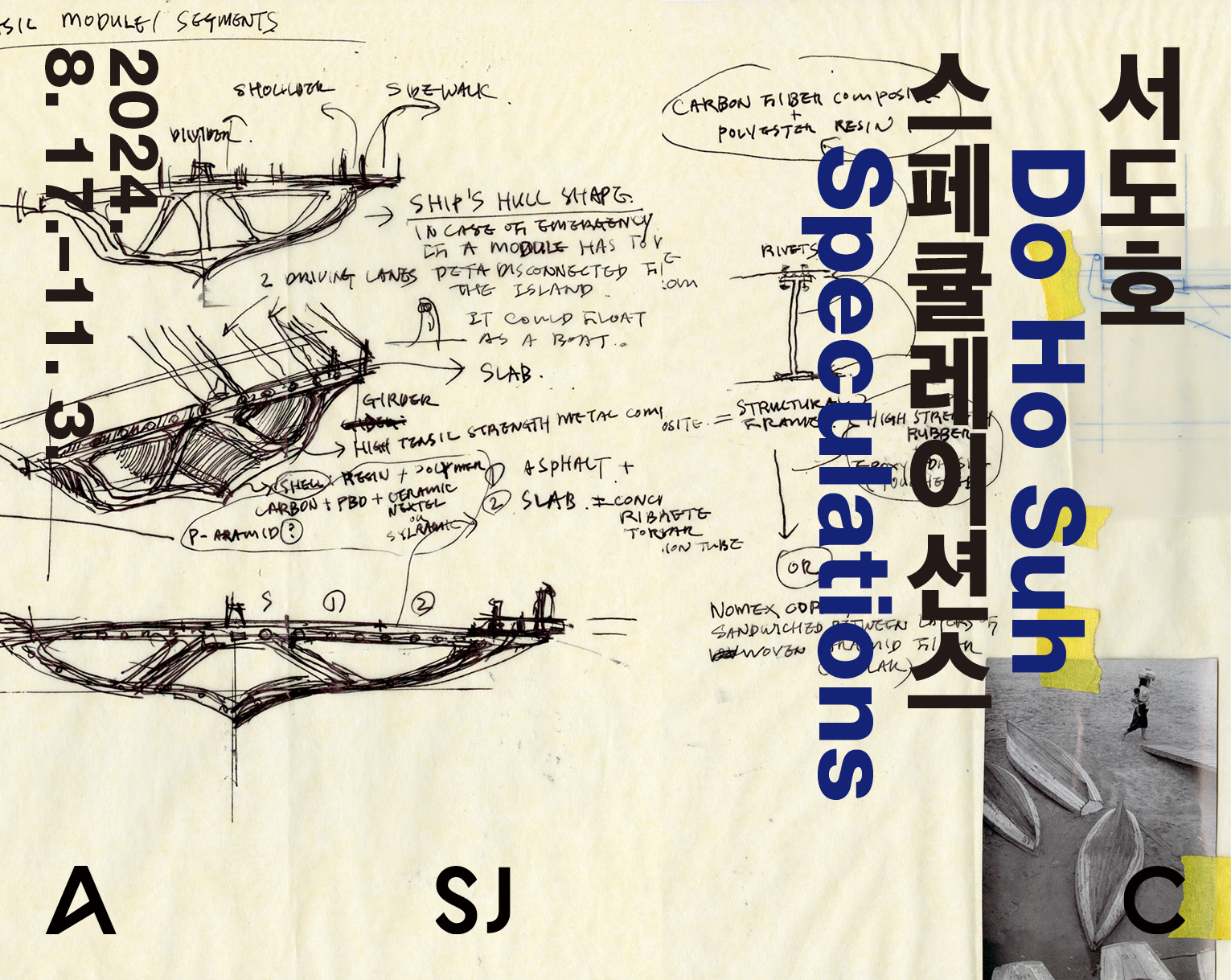

Recently, his solo exhibition 《Do Ho Suh:

Speculations》(2024, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, Korea)

continued his investigation into space and home, leading up to upcoming major

solo exhibitions at Tate Modern, London, UK (2025), further pushing the

discourse on architecture, personal memory, and displacement.

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

Do Ho Suh first

gained international attention with his participation in 《Venice Biennale Korean Pavilion》(2001,

Venice, Italy). His work was later introduced as a key figure in contemporary

Korean art in 《Your Bright Future》(2009, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, USA; Museum of

Fine Arts, Houston, USA). In 《Lesson Zero》(2017, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea), he

reexamined the historical context of contemporary Korean art.

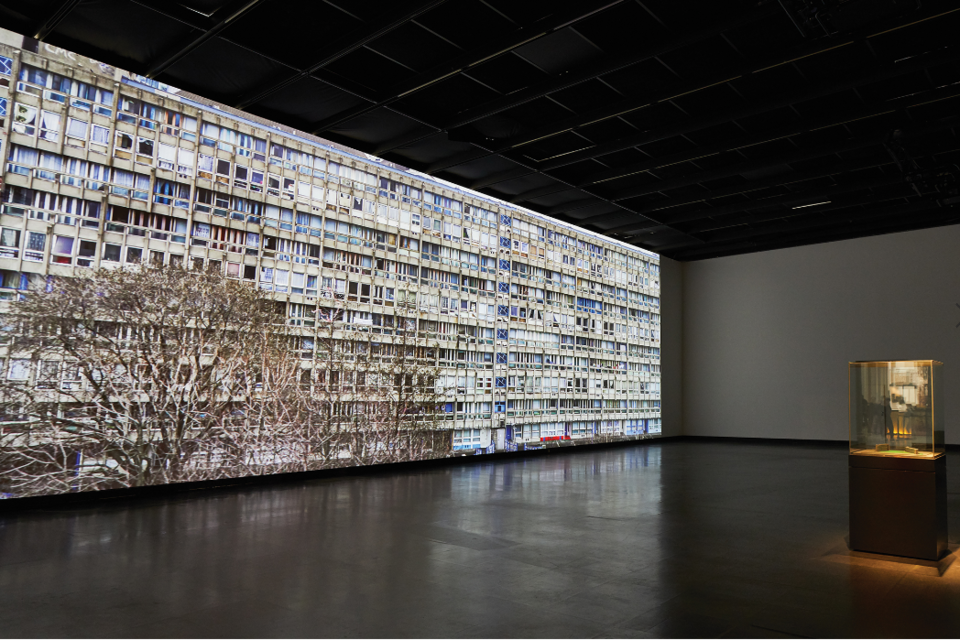

Throughout the

2010s, he continued to explore architecture, memory, and social issues in

exhibitions such as 《Robin Hood Gardens: A Ruin in

Reverse》(2018, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK)

and 《Catastrophe and Recovery》(2021,

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea). His works on migration

and identity were also featured in 《When Home Won’t Let

You Stay: Migration Through Contemporary Art》(2019-2021,

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA; Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis,

USA; Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University, Stanford, USA), engaging in

global discussions on displacement.

More recently,

he has participated in major exhibitions such as 《Super Fusion: Chengdu Biennale 2021》(2021,

Chengdu Tianfu Art Park, Chengdu, China) and 《Kak》(2022, HITE Collection, Seoul, Korea), continuing his exploration of

the relationship between space and human existence in contemporary art.

Awards (Selected)

In 2017, he was awarded the Ho-Am Prize and in 2013, he received the Innovator of the Year Award in Art from The Wall Street Journal Magazine.

Collections (Selected)

His works are included in the collections of major public and private institutions worldwide, including The Museum of Modern Art(New York, USA), Whitney Museum of American Art(New York, USA), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum(New York, USA), Los Angeles County Museum of Art(California, USA), Tate Modern(London, UK), Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art(Seoul, Korea), Art Sonje Center(Seoul, Korea), Mori Art Museum(Tokyo, Japan), and 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art(Kanazawa, Japan), among others.