Nomadism and Glocalism

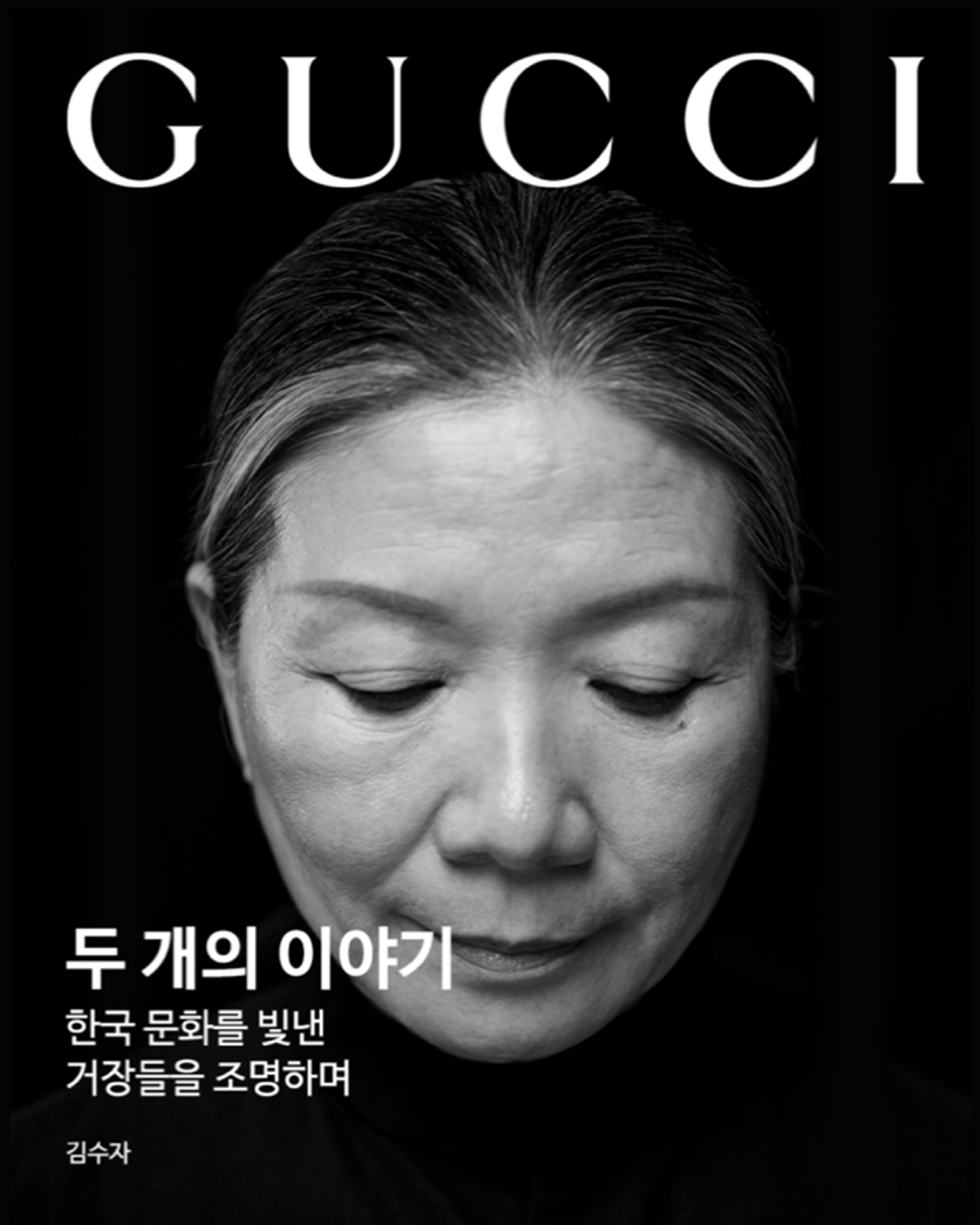

The topic of Chapter 8 is 'nomadism', and the artists under

consideration this time are Kim Sooja (b. 1957) and Kyungah Ham (b. 1966).

While they differ considerably in the tendencies and artistic personality of

their work, they represent a kind of 'dream team' in the sense that they both

practise the ethics of contemporary nomadism through their travels. Kim Sooja

pursues nomadic journeys based on her anthropological interests, while Ham

stimulates and nurtures artistic ideas through travel. Their nomadism has

nothing to do with the sentiments of historical nomads who travelled constantly

from region to region to sustain themselves and satisfy their survival

instincts, nor with the contemporary nomadic life that their descendants

continue to follow. In addition, their nomadism appears quite removed from the

lifestyle of the rapid information age, where transportation and communication

developments create a constant feeling of being 'on the move', and also from

the romantic Bohemians who dream of spiritual wandering and travels to foreign

lands in search of a liberated life.

The nomadism of these two artists can be properly understood in

the context of reflective thinking about neo-liberalism and globalism - two key

issues in the later part of the twentieth century. As is well known,

neo-liberalism is an economic laissez- faire approach that is critical of state

interventions in the market and emphasizes the role of the market and free

activities within the private sector. In addition to its positive impact in

terms of the immense power enjoyed by capital and the boosting of national

competitiveness, it also has negative effects in its disregard for mutually

beneficial lives and redistribution at the community level - as witnessed with

issues of economic downturns, unemployment, the wealth gap and conflict between

developed and underdeveloped countries. This neo-liberalism has formed part of

the backdrop of global tectonic shifts in conjunction with the ideas of

globalism, which involves the use of global systems to seek peace for

humankind, economic welfare, social justice and harmony with the environment.

As both an effect and a driving force of neo-liberalism, globalism, in spite of

its transnational utopian vision, has been subject to non-Western and

developing countries geopolitical critiques from a postcolonial perspective.

The argument here is that the 'globalization' advocated by globalism is

actually a Western- centric standardization that demands a full-scale

re-examination.

In response to First World globalism and its vision of

transforming developing countries in accordance with Western values and

standards, an alternative concept emphasizing locality at the periphery, known

as 'glocalism', has emerged, where non- Western cultures respond critically to

Western influences in an attempt to globally expand their own cultural

contexts. This is an issue related to the neocolonialism that has persisted

even after the official end of the colonial era, and to the postcolonial concern

and alarm over the neo-imperialism that perpetuates unequal international

relationships in terms of politics, economy and culture. This offers the

possibility for linking glocalism - that is, reorganization in a decentralized

manner - to the artistic nomadism of Kim Sooja and Ham, who objectify

themselves while also embracing others through their intellectual and moral

journeys.

As this discussion suggests, the nomadism practised by the two

artists has been an artistic driving force bringing together the world with the

region, and the centre with the periphery. Their nomadism is also a conscious

mechanism for rendering female speakers visible. In that sense, the

gender-specificity in aesthetic terms suggested by Kim Sooja's bottari

(bundles) work and Ham's North Korean 'Embroidery Project' should be mentioned.

Of course, many contemporary artists - both female and male - have employed

fabric-based work and handicrafts as a new plastic language. Yet, in the case

of these two artists, it is notable in the way the thematic inevitability of

'medium as message', in the Marshall McLuhan sense, is prioritized over media

interest or exploration. Kim Sooja's bundles originated in her examination of

the traditional role of Korean women and their daily housework, while Ham's

'Embroidery Project' can be viewed as the result of a 'feminine' approach

devised to communicate with people in North Korea. From this perspective, it is

difficult to separate their artwork using fabric, sewing and embroidery from a

thematic consciousness relating to women's culture and community spirit.

In short, it is necessary to look into the bundle and embroidery

that visualize their artistic nomadism in the context of globalism. Kim Sooja's

bottari are physical and symbolic tokens of nomadism, and Ham's North Korean

embroidery can be read as an expansion into a metaphor of movement, in which a

peripheral handicraft receives renewed attention in both cultural and

geographical terms. In other words, fabric/embroidery become physical

signifiers visualizing the two artists' nomadic consciousnesses. It therefore

stands to reason that their fabric-based work necessarily encompasses thematic

meanings that extend beyond the medium itself. Their aesthetic and political

bearings are fixed at a point where 'women's crafts' intersect with the issue

of nomadism, and their feminist implications may be seen as lying therein.

Kim Sooja’s Bottari

Kim Sooja's bundle-based art shows a fascinating instance of how

sewing and other everyday domestic tasks traditionally performed by women - or

more general practices of managing food, clothing and shelter - are

conceptualized and signified in an artistic context, specifically in

contemporary art.'[1] The matrix out of which the artist's pictorial

fabric-based work and sculptural bundles emerged was her grandmother's

traditional hanbok clothing (which the artist treasures even today) and the

nostalgia associated with it, as well as memories of quilting with her mother.

These artworks have grown and evolved like organisms during Kim Sooja's travels

around the world. First shown in 1992 during her MoMA PS1 residency in New

York, her bottari works have diversified in terms of form, medium and concept

over the course of many domestic and international exhibitions. Sometimes, they

are personified as the artist's body or a woman's body; other times, they take

on a deeper aesthetic and political sense as the formal style shifts to

non-material bundles of breath and light. 'My bundles' containing personal

stories have transformed into 'our bundles' confronting historical oppression

and hardships, and have also expanded into public narratives that reach beyond

the personal realm and become a signifier of the act of embracing in order to

heal scars.

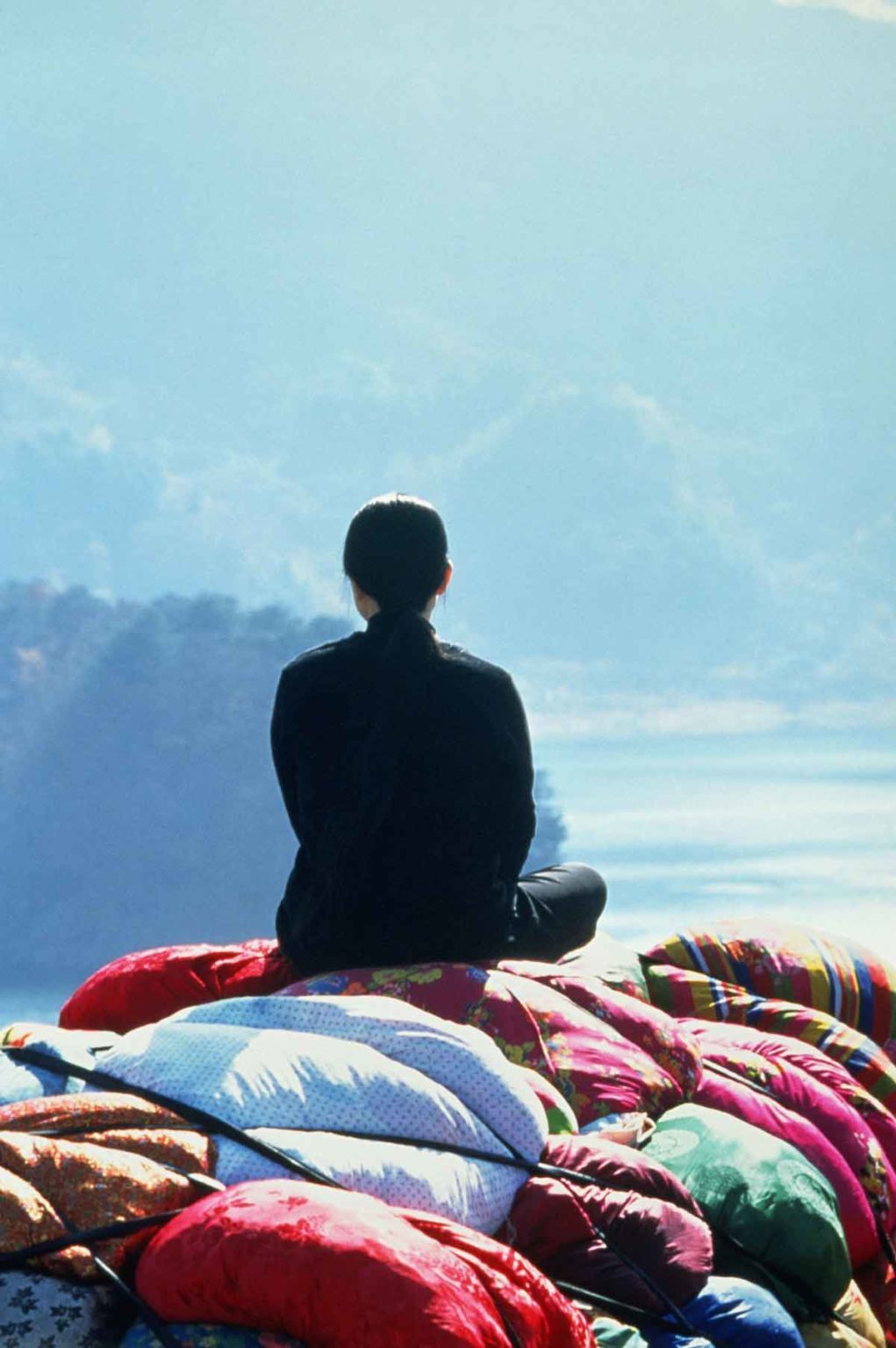

Kim Sooja's bundles first came to public attention through a

touring exhibition that has now become the stuff of legend: 'Cities on the

Move' (1997-99). Planned by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Hou Hanru, the exhibition

was a multi-genre art event that captured the zeitgeist of the 1990s - a time

when a 'New Town' construction boom and new urban culture were in ascendancy,

as Asia developed into a major geopolitical region amid the effects of

neo-liberalism and globalization.[2] For this exhibition, Kim Sooja presented

the work Cities on the Move - 2727 KM Bottari Truck (1997), which became a

milestone in her career. The performance video records her 2,727-kilometer

(1,694-mile)-long journey wandering along Korean village roads beloved by her

in a truck filled with bundles. With the Korean landscape passing behind her,

the lonesome artist is shown only from behind in the fixed frame, sitting atop

her bundles, as if in defiance of contemporary urban phenomena and the concept

of progress, evoking feelings of nomadic alienation and nostalgia. Recognized

as a particularly original interpretation of the exhibition's theme, the work

catapulted Kim Sooja to global renown virtually overnight.

Much like the departing protagonist in her work, Kim Sooja left

Korea in 1999 to move to New York. Recalling this experience in an interview,

she said, 'It was a tremendously difficult situation, but rather than seeing

the stress in this dramatic situation of casting myself out alone in the world,

or defining myself as a cultural exile, my idea was to drive myself to the

limits, seeing it as another future challenge.'[3] It was here at the limits -

living the life of an outsider - that Kim Sooja produced numerous key works of

performance videos contemplating her own sense of existence and suggesting the

healing role of women, such as A Beggar Woman (2000-2001), A Homeless

Woman-Delhi (2000), A Homeless Woman-Cairo (2001), A Laundry Woman (2000), A

Mirror Woman (2002), A Wind Woman (2003) and the well-known series 'A Needle

Woman' (1999-2009).

The first work in the series 'A Needle Woman' (1999-2001) is a

multi- channel performance video filmed in densely populated cities around the

world. Here, too, the artist has her back to the viewer as she stands unmoving

amid waves of metropolitan crowds. Her trademark mise en scène - the motionless

image seen from behind, which evokes inner turmoil - is based on an existential

experience that took place on a Tokyo street. As she was walking in Shibuya,

she explained, there was a 'moment when I was overwhelmed by the cumulative

waves of people and could only stand in [one] place', adding that the 'arrival

of that overwhelming moment was the start of the "Needle Woman" and

that she had the feeling of being 'erased' during her motionless performance.[4]

Yet, in that very moment, she regained her peace of mind and experienced a

sense of 'mediumistic' oneness with the crowd, where she became a 'wrapping

cloth' ensheathing the people and a needle knitting them together. Perhaps this

can be an excitement of empathizing with, feeling compassion for, embracing and

welcoming the anonymous masses.

The second work in the same series was a performance video created

for the 51st Venice Biennale in 2005. For this work, the artist's explorations

were not in densely populated cities, but in cities plagued by political and

religious divisions, civil war, widespread violence and poverty: Patan,

Jerusalem, Sana'a, Havana, Rio de Janeiro and N'Djamena. Presented in slow

motion rather than real time, the video shows spaces that have been exploited,

marginalized and rendered powerless, with the mounting, anguished sense of

tension of urban catastrophe. With her silent, motionless stance, the artist

has already been stripped of her sense of presence, annihilated in the

slow-motion video and by abstract time like a needle that 'disappears from the

place, just leaving the marks of the stitch after accomplishing its role as a

medium of sewing fabric'.[5] She thematizes the light and dark aspects of

globalism and neo-liberalism - that is, the chaos of alternating utopias and

dystopias, the scenes of confusion where the 'First World' collides with the

'Third World', centre with periphery, global with regional, the West with Asia,

stronger countries with weaker ones, the rich with the poor. By transforming

herself into a needle that pierces and stitches, the artist desires to become a

healer taking away the misfortunes that afflict the planet and humankind, as

she also attempts to establish connections with the victims of war, migration

and exile.[6]

As a continuation of 'A Needle Woman', 'Thread Routes' is a

complex statement in which the artist uses her own body to weave together human

beings, nature and the universe. Previously, she featured a sound performance

of breaths, making a medium of the body that had been personified as a needle

and bundle through the work The Weaving Factory (2004). Presented at the 1st

Łódź Biennale in Poland in 2004, The

Weaving Factory was inspired by a vacant former textile factory in the host

city. It was conceived as a piece that would bring the works back to life by

infusing the artist's own breaths and humming sounds - integrating her body

with the empty building. The breathing performance drew an analogy between the

repeated inhalations and exhalations and the crossing of warp and weft threads

or the cyclical horizontal/ vertical structure of stitching. This was developed

further into To Breathe/Respirare: Invisible Mirror, Invisible Needle, which

she showed in 2006 at Teatro La Fenice in Venice. The breaths of the artist and

the audience blended to envelop the theatre, which was transformed into a

vessel for this ensemble of breathing: a feast of breaths and the sounds of

life in place of an opera performance filled the air. For the solo presentation

Respirar - Una Mujer Espejo / To Breathe - A Mirror Woman that same year at

Palacio de Cristal in Madrid, she created another synaesthetic bundle through

the resonance of light and breath, with a rainbow of sunlight refracted by

special film across the building's glass windows to meet light reflected from

mirrors on the floor, thereby enveloping the building and the bodies of those

within.

If this dematerialized bundle enswathing space in breath and light

can be described as a 'post-bundle', this was developed further with Kim Sooja's

exhibition 'To Breathe Bottari' at the Korean Pavilion of the 55th Venice

Biennale in 2013. Here, the artist filled the space with a rainbow of colours

infinitely refracted by the special film covering the pavilion's glass

surfaces. A kaleidoscopic mirroring effect was produced as this light was

re-reflected by mirrors on the floor. As if in response to this spectrum of

light, a sealed, anechoic chamber was set up in one corner. In terrifying

pitch-blackness, the viewer heard only the sounds of their own body: breathing,

coughing, a pounding pulse. Kim Sooja had woven a cosmic bundle where light and

deep darkness coexisted - a bundle of life, where living and death had become

one.

The artist presented another resonant bundle of light and sound in

'Archive of Mind', her solo exhibition for the National Museum of Modern and

Contemporary Art, Seoul in 2016. Alongside her light-based artwork transforming

the museum's courtyard into a luminescent space using the reflections created

by her special film, Kim Sooja showed a new sound-based work entitled Unfolding

Sphere. This work culminates with Archive of Mind (2016), a ritualistic

audience participation performance where viewers are invited to a large

elliptical table and asked to knead lumps of clay that have been placed there,

forming abstract spherical shapes as though creating human beings out of the

substance. As the duet between the friction noises of the clay balls rolling on

the table and Unfolding Sounds, featuring the artist's gargling sounds, ring

out through the space, there is an experience of synaesthetic unity where the

spherical clay bodies become one with the viewers' hands as if encircled by the

artist's wrapping cloth. The message of 'Needle Woman' has been intensified and

expanded as the 'bundle' symbolizing nomadism shifts from geographical to

psychological space.'

Gyungah Ham’s ‘Embroidery Project’

[...]

Nomadism and Hospitality

If there is a common theme connecting the artistic oeuvres of Kim

Sooja and Ham, it is 'establishing relationships'. To begin with, these

relationships are conceptualized through fabric and sewing. Kim Sooja views her

fabric-based work - the joining of cloth - as a mechanism for inclusiveness,

uniting the self with others and the and wrapping world, nature and the

universe. Ham regards her 'Embroidery Project' as a personal, non-linguistic

dialogue with the potential to resolve Korea's political division.

The relationship they are aiming for is driven by a contemporary

brand of nomadism, in the sense that they are actually physically moving and

travelling between places. Their nomadism is distinct from the so-called 'new

nomads' or digital nomads freewheeling figures powered by advanced, ubiquitous

technology. But the way they employ online information as a means of

approaching minority populations and multicultural phenomena, restoring a lost

sense of community and opening up the possibilities for a more socially

participatory, interactive democratization, means they can also be seen as

sharing certain sentiments with the twenty-first- century model of the 'new

nomad'. The important thing is, as mentioned above, that their nomadism

satisfies the proposition of glocalism, which relates to a critical awareness

of Western-centred globalism and neo-liberalism. Their nomadic travels can also

be defined as journeys of artistic and moral exploration, since they are

pursuing new values with anthropological interests and an experimental mindset,

travelling the wastelands with a 'glocal' mentality. In other words, they upend

static reality and stable order through proactive movements that turn natural

places into spaces of praxis, and they introduce instead a reality that is one

that is transformative, alien and vague. In that in the process of formation

sense, their exploratory travels can be understood as the kind of 'spatial

practice' or 'performance of place' described by Michel de Certeau in his The

Practice of Everyday Life (first published in English in 1984).

Through their 'performance of place', these artists make a moral

decision in the interest of global coexistence, human inclusiveness,

correspondence with the other, compassion, and healing in the face of

contemporary disasters and cross-cultural unity. In this way, their nomadism

relates naturally to 'welcoming'. The value of hospitality is found in a free

and liberated spirit and an intellectual richness that is open to all. When

practised in the realm of art, it can achieve astonishing reversals. Through welcoming

that is free of moral controls or conditions, it is possible to go beyond the

cultural and artistic limits, and to resist state ideology and political

violence, doubts and hostility towards others, distrust of the natural

environment, and a neo-liberal political and economic climate that views

economic acquisition as the ultimate goal.

In this context, hospitality is a radical aesthetic catalyst for a

new political art, one that relates to such sharp issues as localism, feminism,

postcolonialism, racism, climate and the environment. The adoption of

hospitality for feminism in particular can be a means of resisting racial and

gender-based oppression and achieving non- Western, non-patriarchal,

non-modernist art through the embracing of subalterns, such as women, the

elderly and disabled people. We can observe an expanded form of feminist art

through the powerful and persuasive welcoming messages to be found in the work

of Kim Sooja, who alludes to the role of women as healers and mediators, as

well as in the work of Ham, who attempts to communicate with North Korea,

thematizing political division through dialogue and a gentle artistic approach.

The rationale for comprehending these two artists' work from a feminist

perspective lies in the way that an inclusive welcoming, an embracing of

others, including those on the margins, offers a potential means of

transcending the self-centred and local-egoistic cultural limits and the linear

constraints of feminism.

[Note]

[1] Kim Sooja, in Woman: The Difference and the Power exhibition

catalogue (Seoul: Sam Shin Gak, 1994), p. 83. 'Women's daily lives are filled

with two-dimensional work, three-dimensional work, installation work, and

performance art. The visual systems associated with clothing, cooking, and

housing are adequate to show certain aspects of contemporary art. There is

washing clothes, wringing clothes, hanging clothes, folding clothes, ironing,

sewing, winding thread, sweeping, mopping, dusting, decorating, preparing food,

shopping, cooking, setting tables, doing dishes, and so on and so forth. It

would not be overstating things to identify the structural logic of

contemporary art as being present here. It's also possible to have a concrete

analysis and appreciation for all the detailed particulars. Because they are

logical and also fascinating. And because there are extraordinary elements that

break apart the monotony of daily experience.It is a conceptualization of

everyday life or the work of women. And at the same time, it is a work of

annihilating myself through that process.’

[2] More than 150 artists, architects, filmmakers and designers

were involved in this exhibition, which toured large cities in seven countries:

Secession, Vienna; MoMA PS1, New York; CAPC Musée d'art contemporain de

Bordeaux, France; the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark; Hayward Gallery,

London; various locations in Bangkok; and Kiasma, Helsinki.

[3] Kim Sooja, interview with Yun Hyejeong, in 'Kim Sooja;

conceptual artist who questions life and existence endlessly', My Personal

Artists (Seoul: Eulyoo Publishing Co., 2020).

[4] Kim Sooja, written interview with the author, 2021.

[5] Kim Sooja, in Choi Yoon Jung, 'A Needle Woman, Sacred Ritual',

in Kim Sooja exhibition catalogue (Daegu: Daegu Art Museum, 2011).

[6] Kim Sooja, interview with Yun Hyejeong, in My Personal

Artists: 'Relations extending to the body, hand, and fabric; the relationship

formed between the footstep and the earth; the relationship formed between the

exhalation and inhalation; the relationship between my eye and the eye in the

mirror looking back at it. Is there anything in this world that is not related?

Everything in our day-to-day lives in the Internet era is

"stitching", and it has become difficult to extricate ourselves from

this web of visible and invisible stitching.’

— 『Korean Feminist

Artists』 2024, Phaidon, pp. 176-193.