Heemin Chung manipulates digital images sourced from the web,

printing or transferring them onto acrylic medium to create multiple layers,

which she then overlaps onto the canvas using various methods, thereby

materializing the textures of digital images. This process begins with

collecting images of flowers, landscapes, and other elements from the web,

which she processes and recomposes using digital tools like Photoshop to create

what she calls a 'sketch' of the work. However, from my perspective, this 'sketch'

is closer to a 'design.' This is because Chung's works are not merely

two-dimensional planes but rather 'non-flat' structures composed of intricately

arranged layers. This 'sketch' must contain all the elements: the shapes and

colors that will be painted onto the primary support, the canvas, as well as

the composition of the acrylic medium that will be folded and layered over it

in various ways. Naturally, the sketch itself is a multi-layered digital image.

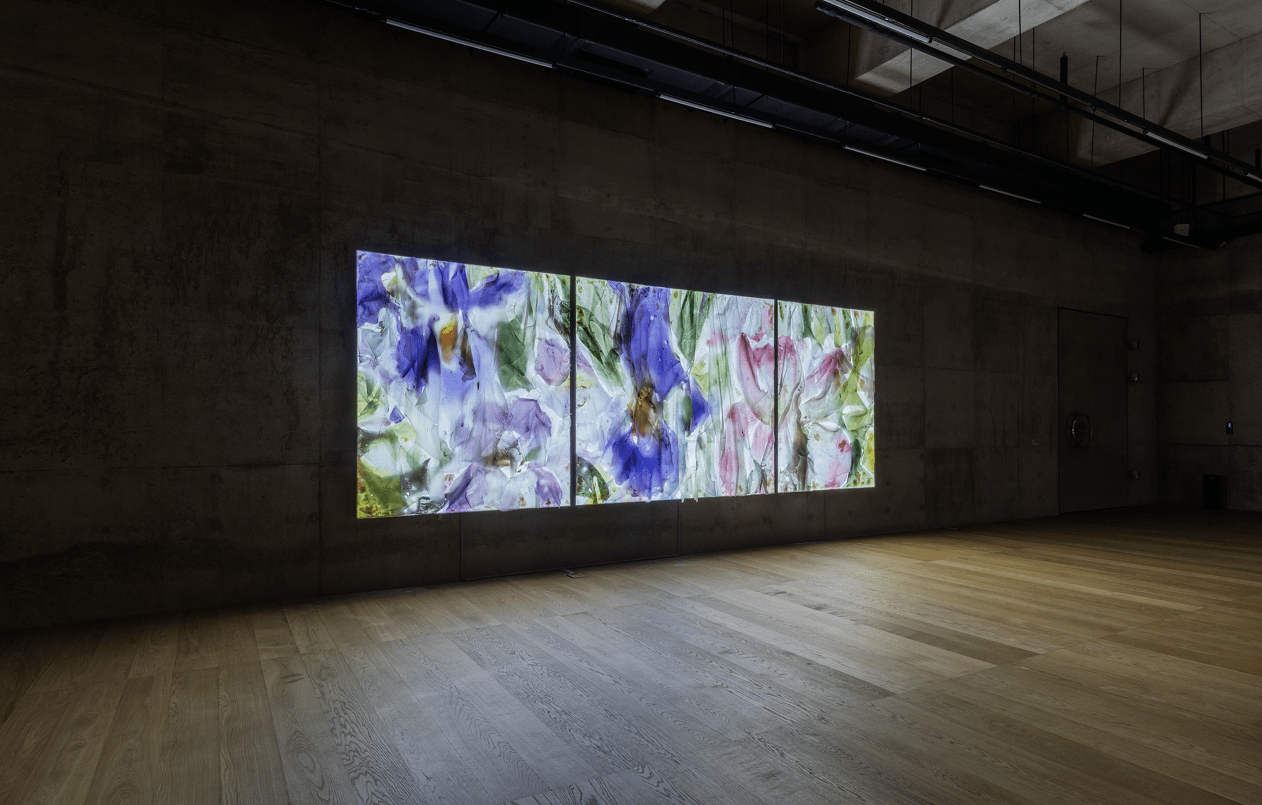

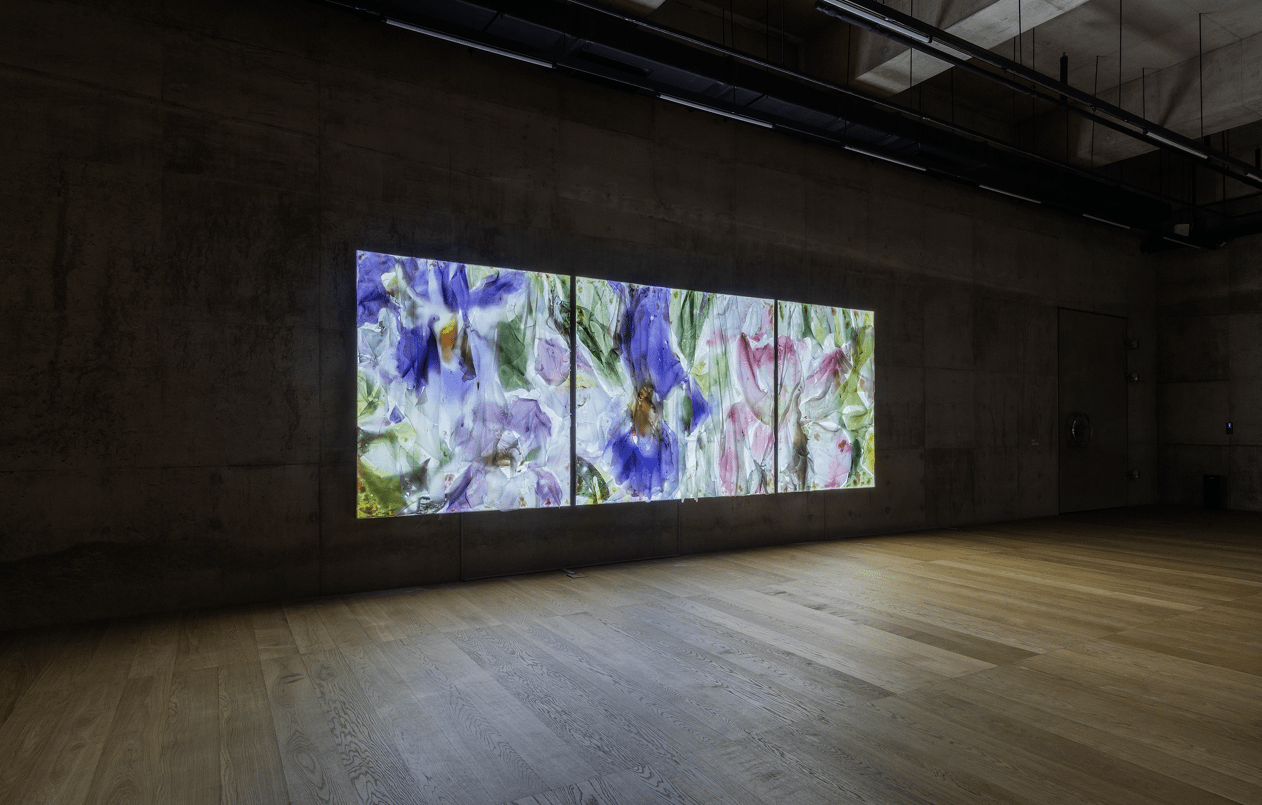

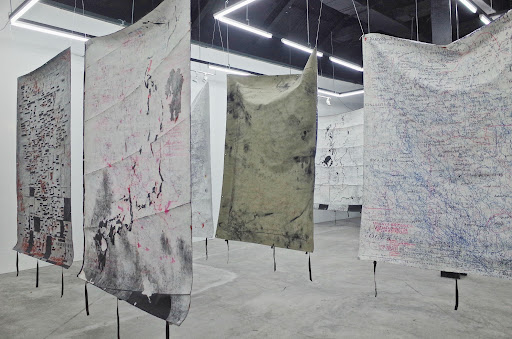

Following this sketch, the artist paints the forms onto the canvas and, using

it as a guide, layers and folds multiple acrylic layers over the surface.

Some of the acrylic medium that covers the canvas is printed with

digital images composed on a computer using a UV printer. Other layers are

created through inkjet print transfers. Chung utilizes acrylic medium without

adding pigment, modeling it into forms and then applying images onto it, or

transferring pigments onto its surface during the drying process to create thin

layers. To achieve this, she spreads the medium onto a flat support and waits

until it dries—several hours in winter, or several days in the humid

summer—before carefully peeling it off like a skin. The detached layers are

then folded or bundled in various ways before being attached to the painted

canvas.

Chung’s distinctive working method, which combines digital image

manipulation and printing with painting on canvas and a kind of collage that

incorporates objects onto the canvas, has so far been primarily discussed in

terms of the "coexistence of the immateriality of digital images and the

materiality of painting" (Hongki Kim) or "the dialectic between

digital and painting" (Jung-hyun Kim). However, I believe it is time to

shift this perspective. Given that most of our daily lives are already

integrated into digital networks and that almost all images we encounter are

digitized, it is no longer convincing to speak of digital images as

'immaterial.' Furthermore, anyone familiar with contemporary painting knows

that nearly all paintings today are directly or indirectly dependent on digital

images. Digital technology is no longer an opposing category to traditional

media such as painting, sculpture, ceramics, or textile art; instead, it

functions as the backdrop for almost all artistic activities today. Approaching

Chung’s work through the framework of "digital vs. painting" fails to

illuminate its individuality.

I propose the concept of "non-flat." The term 'non-flat'

is derived from 'flat,' a word that denotes being level, smooth, or without

curvature. Notably, the term 'flatness' has had an illustrious career in the

history of Western art, thanks to modernist art critic Clement Greenberg.

According to Greenberg, painting must actively embrace "the ineluctable

flatness of the support,"1 as it is "unique and exclusive to painting

as an art form, distinguishing it from literature, theater, sculpture, music,

and other arts."2 The concept of 'non-flat' rejects Greenberg’s premise

that flatness is uniquely intrinsic to painting. However, it does not seek to

revive the 'sculptural illusion' or 'fictive depth' that Greenberg opposed to

flatness. Instead, 'non-flat' aims to remove 'illusion' from 'sculptural

illusion' and 'fictive' from 'fictive depth.' 'Non-flat' is not 'counter-flat.'

Rather than seeking to overcome flatness through opposition, it operates in the

space between flatness and its negation. It aspires to surpass flatness while

still relying on it, transcending flatness without completely abandoning it.

Existing in the tension between flat and counter-flat, 'non-flat' strives to

move beyond the flat plane while remaining within its constraints.

The issue of 'non-flat' has been present in Chung’s work from the

outset. In her 2018 exhibition, UTC –7:00 JUN 3PM On the Table,

she used the 3D modeling software SketchUp to create 3D images of objects like

fruits, knives, straws, and teddy bears, which she then painted onto canvas,

layering thick acrylic medium and oil paint over them. The illusory spatial

depth conveyed by the 3D images paradoxically contrasts with the illusory

flatness of the actual clumps of medium on the canvas, creating an intriguing

tension. This tension of 'non-flat' is fully realized in the new working method

that emerged from Serpentine Twerk, featured in the 2021 exhibition How

I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, and continued through

her 2023 solo exhibition 《Receivers》. Here, she explores ways to transcend the flat plane through the

plane itself by folding, layering, and stacking acrylic medium. Typically,

acrylic is used to create flat images on a canvas, but Chung employs it as a

material for surpassing flatness. She applies the acrylic medium onto a flat

support, allows it to dry, then peels it off, suspends it, binds it, folds it,

or tears it before attaching it to the canvas. These multiple layers of thin,

flat acrylic, stacked and folded like a shell or skin, do not constitute mere

illusion or virtuality but instead create actual undulations—yet they remain

distinct from sculpture. Because they are still attached to the first-level

support, the canvas, their outlines retain their planar quality.

This tension inherent in 'non-flat' is most strikingly expressed

in Plain of the Survivors, featured in 《Receivers》. Chung sourced a 3D image of a

severed tree stump from the web and used SketchUp to generate its inverse

image. She then 3D-printed this inverted model to serve as a mold, which would

typically be filled with medium to create a cast. However, instead of filling

the mold, she spread FRP (fiber-reinforced plastic) onto the inner surface,

creating a thin layer, which she then peeled off and turned into an artwork.

Although the folded FRP layer occupies space like a sculpture, upon closer

inspection, it functions similarly to the acrylic medium in her other

works—folded layers of a plane that generate a 'non-flat' form. Whereas the

acrylic medium, folded and layered onto the canvas, evokes a melancholic sense

of beautiful ruins, the 'non-flat' FRP forms that detach from the canvas and

lie like discarded shells on the gallery floor reinforce a sense of material

dissolution—the loss of solidity, the gradual disappearance of matter over

time.

1. Greenberg, "Modernist Painting," in Art and Culture,

346.

2. Greenberg, "Modernist Painting," in Art and Culture,

346.