There

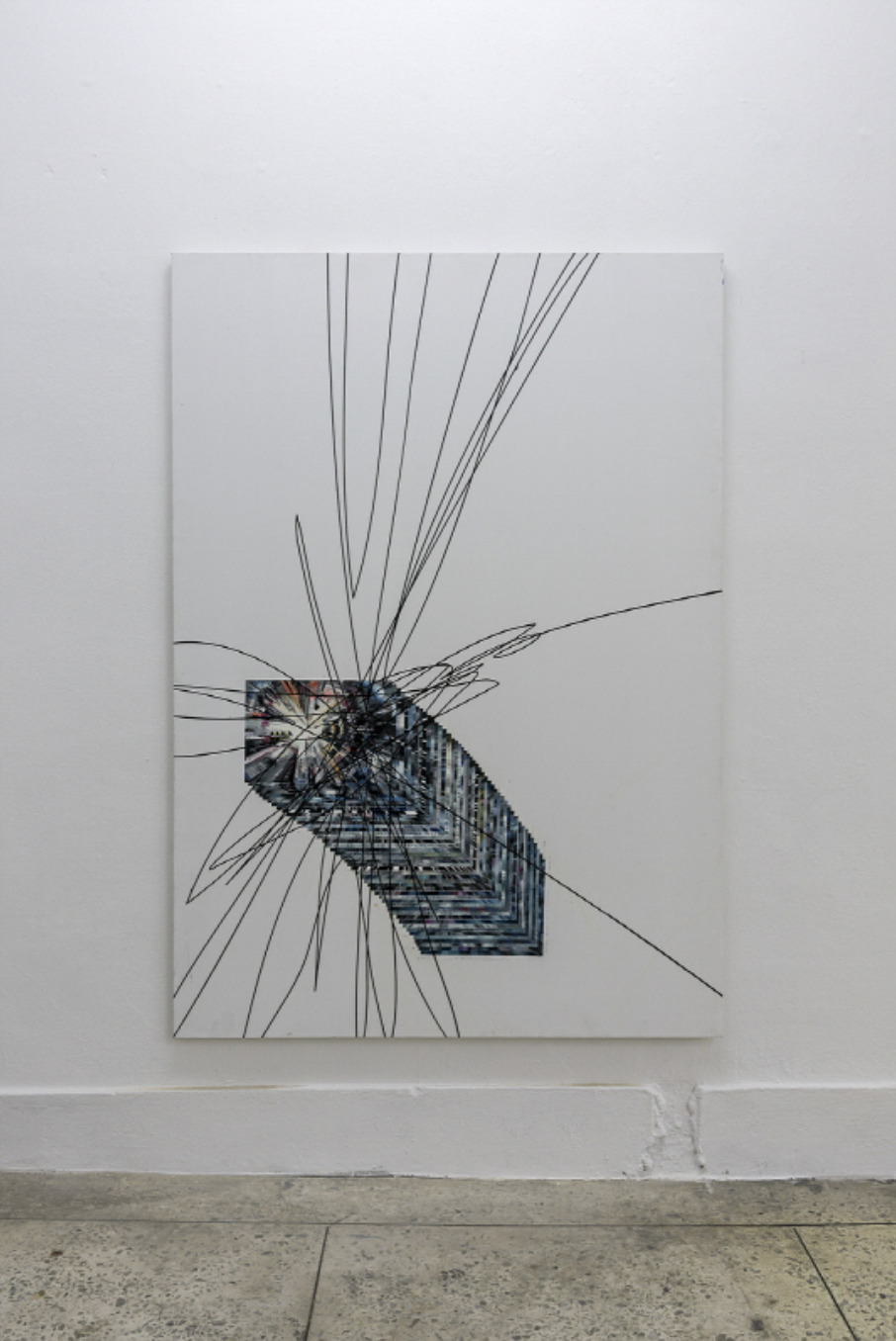

Might be Two Suns (2019) is a composite testimony to this exploration.

. The painting covers three layers: the digital screen, the surface of the

canvas, and the object of reality. It was like a commentary that succinctly

revealed the painter’s concerns, which have been fragmentary and more about

ulterior motive than about the greater cause. First, the painting speaks about

the digital world of the digital screen. The front of the painting depicts

apples that exist as images on a digital screen. On the surface of the apples,

the shadows of a seedling object pass by, which casts sporadic shadows on the

apples, their tops, and leaves, but does not reveal its shape. Notably, the

sharpness and tone of the shadows remain constant regardless of orientation,

whether near or far, left or right, etc. This evokes the characteristic of a

digital environment where light illuminates everywhere on the screen, where

there might be multiple suns, unlike in real life.

After the drawn apple is recognized, we see that the surface of the canvas is

where the apple is painted. A virtual apple that lives in the digital world, or

in other words, an apple that mimics the shape of a real apple, has been placed

on a real object, the canvas. The problem here is that the apple has long been

a fundamental object of exploration for painters who have honed their skills in

the art of painting. Painted on the front of the painting, the apple as a

“primary subject,” the artist approaches her painting as an allegory to the

history of painters who have used the sphere as one of their basic shapes and

as a tool to cultivate their skills. The apples brightened by the light and the

appropriately contrasting shadows that are only shaded. Depictions that follow

the curved shape of the apple, protruding from the depths and gradually

spreading downward with backlit and half-lit areas. The color of the apple,

painted in a fine range of light green and purple. There’s an exploration of

the fundamental processes of painting that one might expect to find at the

beginner level. And this exploration reveals the painting to be a study in

still life itself, as it is usually the subject of painters who create still

life paintings.

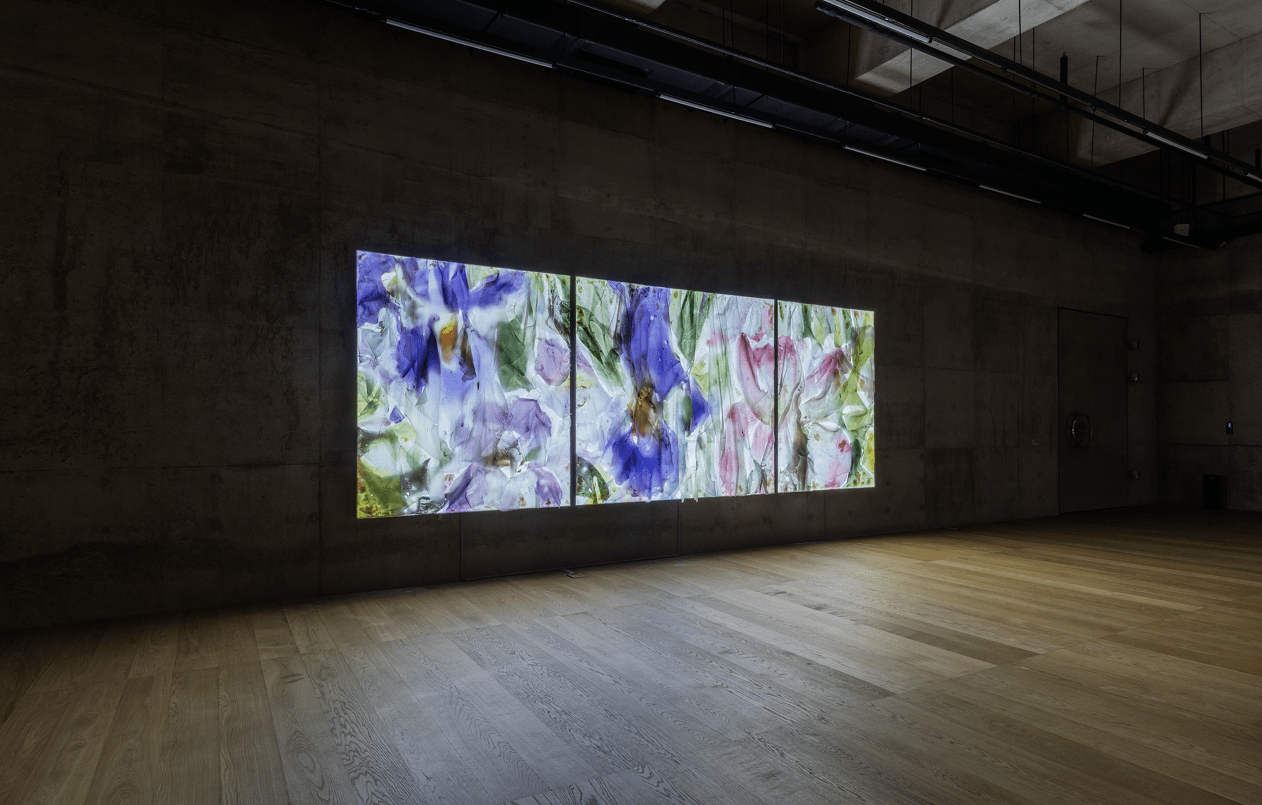

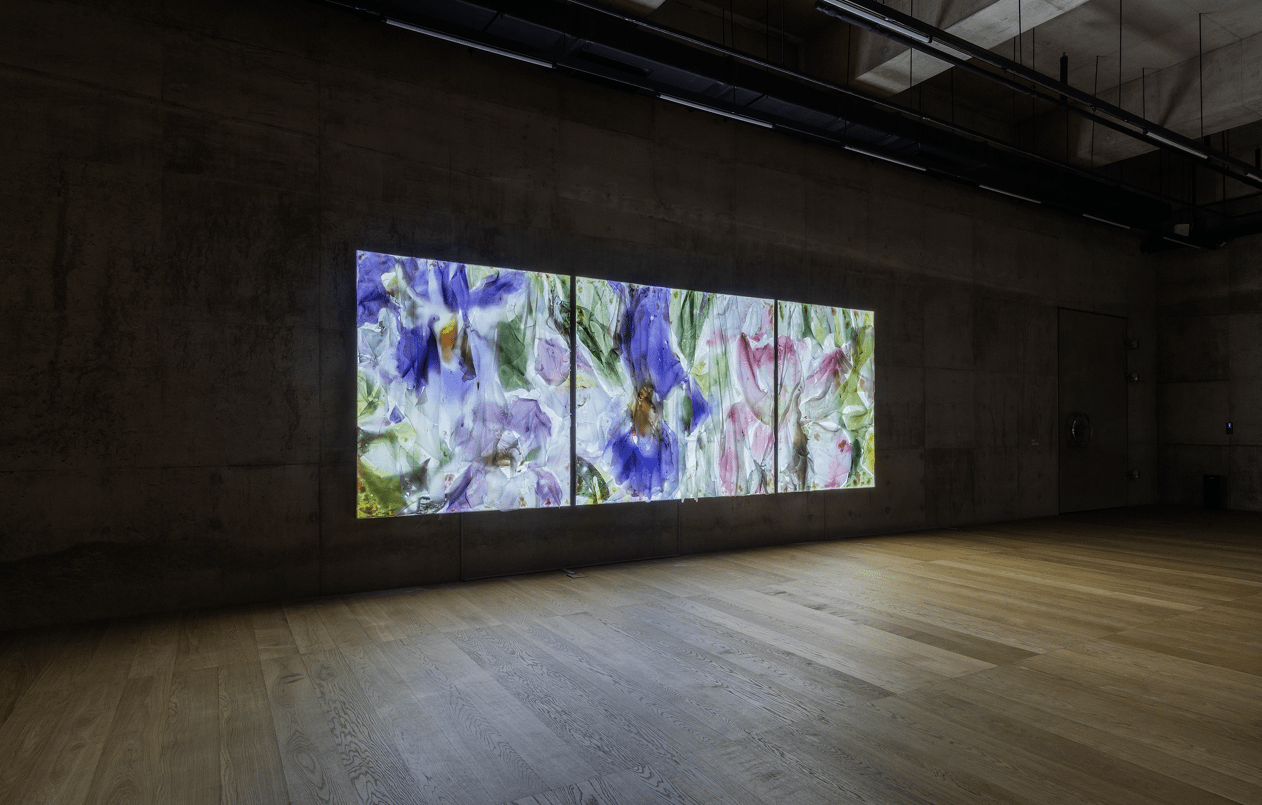

The final layer of the painting is the fact that it has become an object in

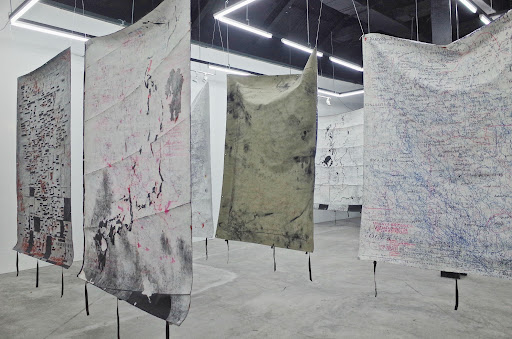

itself. As the exhibition preface explains, “I would like to place today’s

still life paintings as “suspended objects” in an exhibition space like a

halved watermelon,” 3 the painting filled one wall, right

next to the entrance to the small room of audiovisualpavilion, like a newly

painted wall. It cuts through the space of reality, as if slicing through a

cross-section. At this time, the light of the sun from the entrance

illuminated the painting: the space where the apple she initially brought as

the subject of the painting was originally located was a digital world in which

multiple suns coexisted, but in the final stage, it had entered the space of

the here and now, where only one sun exists. This gives the painting an

identity as an object placed in real space, beyond the possibility of

reproduction or a laboratory for technological exploration, and takes on a

third layer beyond the double layer of digital screen and canvas surface.

The methodology of imitation

By the time Heemin Chung released her apple painting to the world, in 2018, a

year earlier to be precise, her interest had expanded to the thickness of the

paint layer. For her, thickness actually refers to the thickening of a

material, particularly the concept of thickness as it is understood within the

genre of painting and what is realized through paint. The source of her

interest in thickness is in acrylic, a material she chose to overcome the

technical constraints of oil paint, and the reason for her interest in acrylic

is that it employs a methodology of imitation to assist oil paint. During this

period of transition in her practice, she devised a method called

“modeling.” In her hand was Gel Medium, a supplement that maximizes the

effectiveness of acrylics. As a painter, her concerns in the apple painting

extended to painting with thick layers of water-based paints, and gradually,

she captured the chain reaction between the three substances in her paintings:

acrylic as a device to imitate oil painting, and gel medium as a device to

support acrylic.

Acrylic

is a material intended to improve the art of painting in terms of efficiency

beyond the limits of oil. In most of its effects, such as color, gloss,

and texture, acrylic mimics oil painting. This means that acrylic is not a new

material that has never been used before, but rather a material that has been

developed from the history and role of oil, a material which acknowledges oil

as its parent, and therefore, with some exaggeration, has the properties of a

substitute. As always, oil, the most traditional medium for painting, is an

oil-soaked material that requires a great deal of time and effort to build up a

physically solid layer. To overcome this slow drying and thinness, acrylics

were developed, which are paints based on water rather than oil.4 Because

water-based acrylics do not contain slow-drying oils, they can be airbrushed to

create thin, clean layers, or thickened to create chunky layers quickly.5

Gel

medium, meantime, is a supplement that comes in gel form, as the name implies.

When the pigments that give acrylics their color are removed, all remains is

the binder, the substance that binds the pigments together and makes the paint

stick to the canvas. The clear, sticky binder is made into different types of

mediums with varying degrees of gloss, viscosity, and unique additives (such as

glass, sand, etc.). Gel medium is not just paint that can be spread, but can be

“sculpted” into three-dimensional shapes by adjusting their thickness with a

brush, knife, or hand. These materials turn the paintings that have been

characterized by the projection

of the third dimension onto the second dimension into objects that actually

belong to the third dimension. Of course, in the process, if a painting is

always based on a canvas, it does not become a sculpture. It just exceeds the

sculpture’s task of dealing with the three-dimensional world.