Chu Mirim has consistently observed urban landscapes and

translated them into geometric two-dimensional works and installations. Her

works incorporate pixel-art-like units, either individually or in combination,

to depict everyday life in the city. For an artist who was born and raised in

an urban environment, it is natural for her experiences of city life to form

the foundation of her work. Likewise, as someone from a generation familiar

with the internet and computer interfaces, it seems only natural that her

visual thought process is influenced by digital media.

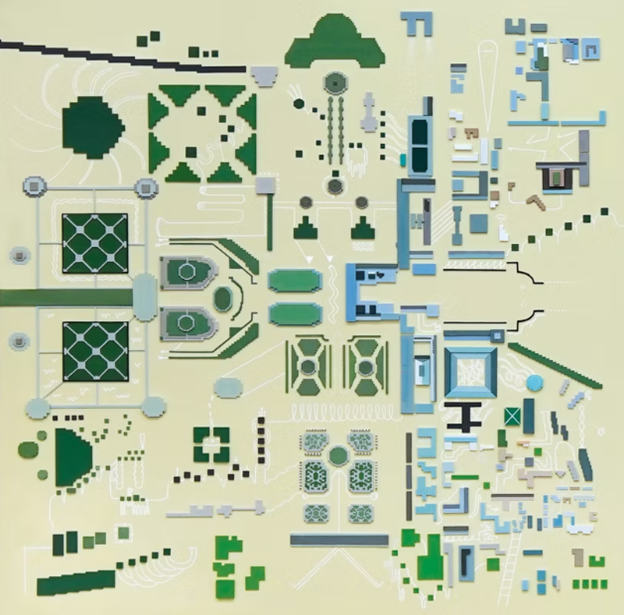

Her solo exhibition 《Satellites》, held at Gallery Lux, showcased

works depicting everyday life and landscapes in Seoul and its surrounding urban

areas, including apartment complexes, dense clusters of buildings, and the

roads that connect cities. This exhibition was particularly significant as it

reflected the artist’s personal experience of moving through Seoul’s satellite

cities since childhood. Chu happened upon a copy of her Resident

Registration Abstract, where she saw a record of all her previous addresses.

This document was not just a personal record of movement but also a testament

to her family's life, which had been inevitably influenced by three decades of

Seoul’s urban expansion, real estate policies, and the development of new

satellite cities.

Yet, the exhibition does not dwell solely on individual memories;

rather, it evokes the shared experiences, aspirations, and disappointments of

many who have lived amidst high-rise apartments and skyscrapers. Beyond the

pursuit of a comfortable life, the exhibition reminds us of the disillusionment

and struggle of chasing the myth of real estate investment. While the works and

the exhibition itself are imbued with nostalgia for the artist’s childhood and

a warm, understated humor about urban life, they do not erase the harsh

realities surrounding real estate and urban development.

Pixels and Windows

Chu Mirim describes herself as someone who exists in both the

physical city (offline) and the internet (online). She emphasizes that the

online environment, connected through computers and the internet, is just as

integral to her life as the tangible urban environment. Having first worked as

a graphic designer before transitioning into an artistic career, she is deeply

familiar with computers and the internet—not merely as tools, but as mechanisms

that shape computational thinking. For Chu, the desktop

screen of her computer serves as a kind of sketchbook. Her working process

begins with all necessary windows open on her desktop, making it both the

source and the starting point of her creations. In her work Interface(2020),

she constructs a composition reminiscent of multiple windows, graphic units,

and grid lines, suggesting that the screen itself is her personal workspace.

Had she used a horizontally elongated canvas similar to a monitor’s aspect

ratio, the connection to a computer screen would have been even more direct.

However, she deliberately used a vertical canvas, approximately the size of a

typical room window, making it resemble an architectural window rather than a

digital display. As a result, the composition appears as if it is framed by a

window through which one views the city’s divisions and structures—yet, since

it originates from Chu’s digital workspace, this transition feels natural.

In fact, architectural windows serve as a significant framing

device in her work. The geometric forms derived from building exteriors and

window grids become both formal elements and narrative structures. In Castle(2020),

Chu presents a series of works resembling apartment elevations,

referencing large-scale branded residential complexes. The title hints at the

class consciousness embedded in real estate, but the content reflects both

reality and the artist’s romantic imagination. Using bright acrylic sheets cut

into geometric shapes—squares, rectangles, parallelograms, and triangles—she

constructs a colorful façade that resembles cityscapes filled with

high-rise apartments. Within these geometric frames, she illustrates scenes and

moments that could be observed inside or outside such buildings. Some images

even resemble emojis, evoking the familiar icons of smartphone chat

applications. These pictograms and symbols collectively depict the multifaceted

nature of life in both online and offline spaces.

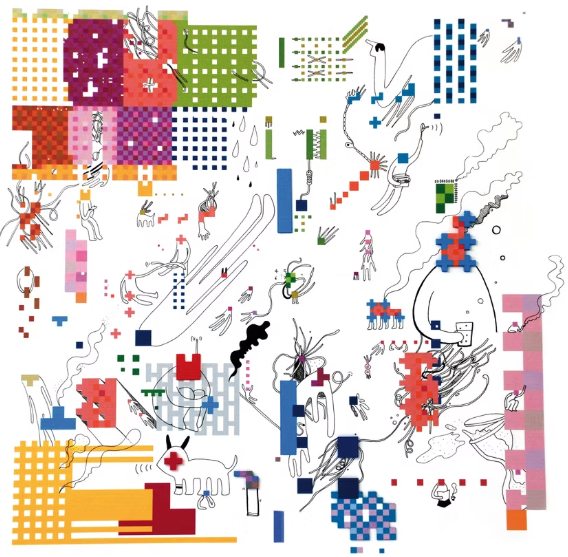

A similar approach is evident in the video work Windows(2020),

where Chu creates multiple animated scenes within frames shaped like squares,

rectangles, and stair-like structures. These visual fragments include views

of apartment complexes, satellite navigation maps, comet trajectories, and

emojis—all elements associated with urban structures and digital screens. At

one point, the artist zooms into a satellite map until individual pixels become

visible, emphasizing the digital construction of urban imagery. Her works are

often mistaken for digital prints due to their clean lines and smooth

color fields. While her paintings are frequently introduced as pixel-based

paintings, it is important to clarify that they are not derived from

pre-existing digital blueprints but are hand-drawn works on paper.

When discussing pixels, many assume that “pixel = square”,

but pixels are merely the smallest units of a digital image—they are not

inherently square. However, because bitmap images often display grid-like

patterns when resolution decreases, many associate pixels with small

squares. Chu extends this concept, connecting pixels to urban windows,

metaphorically framing everyday city life through these digital-architectural

correspondences.

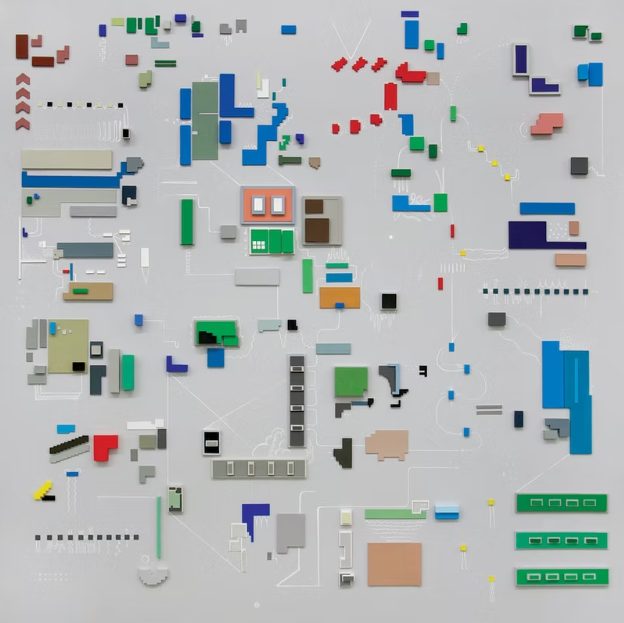

The Drifting Ones

In this exhibition, Chu reflects on her experience of constantly

relocating as Seoul’s satellite cities expanded. Satellite cities are

secondary urban centers designed to absorb population overflow from major

metropolitan hubs, and in South Korea, many suburban cities function

as dependent satellite cities rather than self-sufficient urban

entities. Since the 1990s, South Korea has rapidly developed new planned

communities, such as Bundang and Ilsan, which were followed by numerous

other New Towns. Having grown up in these rapidly constructed cities, Chu

frequently moved due to her father’s job relocations and real estate

investments, leading to a childhood of constant adaptation. She recalls how

these new cities, built under rigid urban planning, felt artificial

and impersonal, leaving her emotionally unanchored.

Her work Sweet Section(2020)

represents Seoul, the ultimate destination in South Korea’s real estate

aspirations. Unlike the actual complexity of Seoul, her depiction is more

relaxed, softened by a pink-toned background, making it seem like an idyllic,

comfortable city. Flanking this work, Icy Moon(2020)

and The Rabbit Hole(2020) reflect her thoughts on

satellite cities. The uniform cityscapes reminded her of Saturn’s icy

moon, Enceladus, evoking a cold and distant feeling. Meanwhile, the hidden

pedestrian paths connecting different cities—known only to local

residents—often became sites of territorial disputes. In Flyer.002(2020),

she highlights the interchangeability of real estate marketing slogans,

demonstrating how identical promotional phrases could be applied to various

cities like Wirye or Misa without seeming out of place.

The exhibition visually conceptualizes Seoul’s relationship

with its satellite cities by likening them to the dynamic orbits of

planets and satellites. Works on the gallery walls were connected

by curved lines and dots, visually echoing planetary trajectories. This

arrangement made each piece appear like a celestial body floating in

space, reinforcing the theme of movement and displacement. The strongest sense

of weightlessness emerges in Interchange(2020), which

depicts a highway interchange—a transitional space between cities. The

circularly arranged trees and overlaid arrows resemble Andy Warhol’s Dance

Diagram(1962), evoking a sense of choreographed motion. The

circular movement suggests a light, buoyant dance, a fitting metaphor for

those drifting between Seoul and its satellite cities.

Finally, the artist presents Bubble Walking(2020),

a self-reflective work depicting a figure walking inside a bubble. Unlike

the real estate bubble, this floating sphere allows Chu to drift

freely between Seoul and its satellite cities. If there is no stable ground to

stand on, why not imagine defying gravity altogether?

In a time when housing insecurity has led to terms

like “jeonse refugees” and “hotel

squatters,” perhaps floating above the city is the ultimate form

of freedom.