Mun: The core elements of your

new work seem to be related to an exploration of the basic structure of video

(film), i.e. light, camera, projector, screen and spectators. The projector in

this case is not only a device that passively projects generated video, but

also acts as a light source for the camera on the opposite side. The screen

also is a passive surface on which the projected video is played on one hand,

but is the stage of a show taking place before it on the other hand. While

movies have a unidirectional structure, as the light from the projector hits

the screen and the spectators also face the same direction, you created a

two-way closed system by overlapping this structure. This is what gives the

work conceptual and structural tension. I think your omission of concrete

images from the generated image (G) was also an appropriate choice. For the

video to simultaneously function as light, contents (images) would be

interference. Showing the texture of light itself is more effective. In that

sense, I think the noise of the pixels breaking up and the flickering effect

well embody the nature of light in the digital era.

There are many examples of infinitely reflected live video closed-circuit

systems, such as Dan Graham’s Present Continuous

Past(s) (1974). But while many previous precedents created

closed systems of infinite reflection by using mirrors, your recent work uses

two cameras facing one another to create a reflexive closed circuit. In this

case we can perceive that there is a different focus. For instance, the cases

using mirrors are most likely emphasizing the aspect of time. While the mirror

represents the present, the recorded video represents the past, because even if

it is taken real-time, there is bound to be a time difference. Therefore, the

infinitely reflected video images are like strata of time—endless layers of

pasts from a few seconds earlier, interlocked with the present. Meanwhile, in

the case of your new work, the emphasis seems to be on the gaze, not the time.

The two cameras facing one another are a mutual gaze, and the viewer’s

experience of facing the screen on which his/her image is being projected, also

reveals a strong aspect of mutual staring.

Park: Correct. A core part of the

effects I intended for the new work is related to the gaze. There are two

projections and two cameras, and the spectators go between them. Here, the

spectators are penetrated by the two-way gaze taking place. Perhaps this is a

feeling similar to that of going into the middle of a densely woven two-way

laser mesh. The emotion I felt as I devised and tested this structure was fear.

I felt like I was being inserted into a surveillance circuit and my body was

being severed. The tension occurring between the two-way gaze, and the fear of

the body being pierced there, is the foundation of my work. Meanwhile, the

sense of fear is also caused in a somewhat different direction—the fact that

the live video does not continue. If the picture suddenly changes after the

live video has been showing me, it feels as if I have suddenly disappeared.

It’s something like the feeling of my existence being erased. First I am in a

stable structure, and then suddenly the space changes regardless of my will. At

this point, there is a sense of disorientation, not knowing where this is.

Mun: As for the last part, I

cannot make an exact judgment, since I have not experienced it yet. I

understand the transition of the picture gives the feeling of sudden severance,

but the feeling of fear would be different depending on the person. In the

sense that the mirror image, which lets me perceive that the camera is looking

at me, shows me and the space I belong to, it could be an image of a stable

world; however, to someone like myself who does not like to be the object of a

gaze, the reflection may be uncomfortable. In this case, the transition of the

screen image and the disappearance of my image may not be fear, but relief.

Park: Perhaps. Anyway, for me the

sense of disorientation was important. Another thing I intended in terms of the

gaze was to give an uncanny feeling when a screen was projected on another

screen, as if the screen was looking at me. If the camera positioned behind me

takes my rear image and projects it on the screen behind me, my rear

appearance, which I am unable to perceive, will appear behind me. To perceive

this is quite frightening—the chill you feel when you realize that someone has

been watching you without your knowing.

Mun: That I can easily agree. It

reminds me of Lacan’s allegory of the “sardine can.” The fear of an

object/other gazing at me is universal. But what intrigues me here is not the

fear, which is the consequent effect, but the structure that induces it. In

this case, the introduction of interactivity to the traditional one-way

screening structure, the unpredictable and irregular transition of scenes,

rather than presentation of a complete video, intervention of spectators in the

feed-back loop, and kinetic robots acting as triggers for the transitions of

the video are all characteristics that make your work different from the

classical film structure. To me, your work seems traditionally filmic on one

hand, but also seems post-filmic on the other. Of course the concept of the

filmic here does not refer to the aspect of contents, such as narrative, but to

the structural aspect. It is interesting that you are based in extremely

traditional devices (camera, screen, projector, light) and concepts (the gaze,

for example) of filmmaking, but twist them. This characteristic can be seen not

only in this piece, but throughout your body of work. You have a solid ground

on film, and the formal aspects have always been important in your entire

works.

Park: I agree. In a way you could

call me a formalist (laughs.) In fact, I did receive thorough

training in filmmaking, and I am accustomed to looking at objects through the

camera frame. While the formal aspects are always important, I don’t tend to

make conceptual approaches when I plan my work. My senses react before the

concepts. For example, in the case of A Dream of Iron (2014),

my guideline for editing was sense rather than concept. I stress the rhythm

according to the difference of texture, for instance, something calm comes at

first, and then something hot comes. In the multi-channel version of A

Dream of Iron, the major axis of editing was the transition from

the vertical to the horizontal. First the image, and then the concept follows.

The images that are hanging or standing vertically, later lie down. I start

with vertical images such as whales standing up straight, a ship hung up to dry

upside-down, and a pillar of fire, and finish with iron plates neatly stacked

horizontally. This can be interpreted as the end of symbols visualized by

verticality (industrialization, masculinity, iron, dictatorship, etc.). But I

am not mobilizing images in order to explain grand narratives. It is more

appropriate to say that the images and sounds correspond to my intended

emotions or senses, which then can be interpreted by the audience as concepts

or symbols.

Mun: Considering that senses or

emotions lead directly to the composition of image or sound, it could be said

that your form leads your contents. But let us now return to Mirror

Organs. At first glance your works seem to be separate, without many

commonalities, but if we look closely, there are many instances where elements

from previous works are used in variation in your subsequent works. Even in

your new work, a dark shadow of your former work seems to be cast upon it. For

example, the kinetic object, which first appeared in Space

Time Machine (2015), is fully implemented in Mirror

Organs. To my knowledge, the idea of live video was also first

attempted in Space Time Machine. Conceptually,

what is directly connected to the new work is this aspect of live video, rather

than kinetic factors. So what did you gain from Space Time Machine, and how was

this connected to your later works?

Park: Space Time Machine was

a work in which I experimented with the tension between video and actual

objects. The work features two different types of machines that make space and

time. One is an object that actually moves as it creates a sense of time and

space, while the other is a video that creates virtual time-space. The movement

of the object is filmed live by a camera and projected back onto the object,

which acts as a kind of reflector, thus interfering with the video image. (In

result, the projected image and the movement of the object correspond with one

another in real time, changing endlessly.) What I confirmed in this work was

that the video appeared much more realistic than the actual object. The

movement of the installed object was too slow, and therefore hard to determine

whether it was actually in motion; but in the video the movement can be seen

much more clearly. Though this can be interpreted as the ontological difference

between the illusion and the reality, what was more interesting for me was the

tension, which could be sensed when seeing the real thing and the image at the

same time.

Mun: I suppose the work in which

that point was specifically expanded was last year’s live performance

video, Stairway to Heaven (2016). That was

the first time you applied the concept of mirror reflection in your work,

and Mirror Organs also looks like a

modified live performance, in which you have replaced the actors of Stairway

to Heaven with robots (guns). The formal core of Stairway

to Heaven was the gap between the real (performance) and the

image (live video of the performance). Please explain this structure.

Park: In Stairway

to Heaven I wanted to show the tension between what the

camera showed and what could be seen with the naked eye. With our eyes, we

usually see the background as well, and the whole body of the performer. On the

other hand, with the camera—especially in close-ups—I can exaggerate a

particular facial expression or a certain part of the body. The actual movement

is exaggerated or diminished as it is transmitted to the screen, and a certain

tension is formed in this dislocation. For example, it is difficult to see the

detailed expressions of the actor with our eyes alone, but with the camera we

can capture the delicate emotions revealed by movements of the eyebrows or

mouth. But my intention here was not to use video as a complementary measure

for the eyes. Rather, I wanted to show the tension that occurs when two

different states coexist in a singular vision. In this work, spectators

simultaneously look at the video inside the frame and movement of the actor

outside the frame. That is because the performers before their eyes move

continuously, and the live images projected on the screen deceptively

correspond to reality. While jumping in and out the cycle of absorption and

detachment, I wanted to create a state of not being able to empathize

completely with either side, or the emotion of feeling both states at once. I

once felt the same feeling I had previously while driving alongside the Pacific

Ocean in California, when actually I was driving along a highway on the west

coast of Korea, looking at the sunset above the horizon. It was not a

recollection of a memory, but a strange experience, as if I was feeling the

state I had felt before, simultaneously here and now. I wanted to somehow

express this state of being synchronous.

Mun: Since your performance only

took place at the opening, and after that there was only the video, it is hard

for me to determine if that gap was actually well-embodied, as I could not make

it to the opening. But presumably, the double structure you intended would not

have been successfully communicated. There are two main reasons for this: one

is that because there is a narrative, the majority of spectators would have

focused on connecting the scenes in order to understand the story. Particularly

since the story was based on a famous TV drama, and the emotional line was

powerful and sensational, viewers would have had to pay close attention to

understanding the relations among the characters and following the fluctuations

of emotions. Another factor is the music. It is my understanding that you used

Spanish guitar music to help the performers’ emotional acting; however, because

the music is so sentimental, viewers would have been immersed in the emotional

acting of the performers, rather than seeing the structure inside and outside

the frame.

Park: I agree in the larger

context. In the case of the music, I removed quite a bit of it during

re-editing because I thought it was too much. As for the story, it is

indispensable in terms of my work intention. I thought the behavior of the

drama’s main characters, who betrayed their own emotions and were swayed by

their surrounding situations, reflected Koreans in general including myself. I

thought the desire mechanism of myself, from which subjectivity was excluded,

reflected a characteristic of Korean society, and I intended to reflect this

through the narrative structure of the drama.

Mun: How does the intention

concerning the contents you just described connect with the formal composition

of repeating absorption and detachment?

Park: The protagonists of Korean

TV dramas appear to react according to external situations, rather than acting

according to their own feelings. Behavior is often decided according to

situations given from the outside, such as human relations, economic or social

backgrounds. Emotions also seem to be formed under the influence of external

factors. The self is already relational. The emotional basis for making

decisions don’t occur through an internal mechanism, but are injected from the

outside. If they were “personal” emotions, the characters would be able to be

immersed in one another completely based on their own decisions and

subjectivity. This does not happen, as we are always looking to see what others

think. But since this does not mean there is absolutely no subjectivity, they

remain in an ambiguous state, unable to keep distance nor be completely

immersed. I wanted to express this strange dual emotional state, in which the

characters go back and forth from being immersed and not being immersed, which was

embodied through multiple viewpoints that divide inside and outside the frame.

Mun: The intermediate nature of

shuttling between inside and outside the frame seems to be something that

appears in all your works, not just Stairway to Heaven. After all,

you are also on the border, not belonging to either Korea or the United States.

Even works like A Dream of Iron and Cheonggyecheon

Medley (2010), which seem to have little relation to Stairway

to Heaven, have some similar points, including the attitude of

the camera approaching the subjects. In these cases, the camera does not

completely empathize with the subjects, nor does it assume the perspective of a

complete outsider. It maintains a dualist state with one foot in and one foot

out. It is the same with Army (2016). I

once asked my students about this work in class and got the most diverse

responses, from a comment that the viewer was offended because it felt like a

foreigner observing Korea, to a response that perhaps the artist was

empathizing too much with the subject matter because he had joined the military

service too late, along with many other comments depending on the students’

gender or whether or not they had served in the military. Such dispersed

reactions have something to do with the specificity of the subject matter of

military service, but I believe it also can be attributed to the fact that the

angle of the camera was half attached and half separated.

Park: I believe the term

“intermediate” can be confusing. I don’t think an intermediate attitude is good

in life. Jumping in completely, and jumping out is my basic attitude. For me my

work is part of the exploration of my subjectivity. As an East Asian carrying

the burden of historical mutation, in order to know who I am, what I want, I

must come out from the frame (national, cultural class or gender) I belong to.

I must jump outside the frame to see what frames me and jump right back in

repeatedly. Meanwhile, in order to sustain subjectivity, I must be completely

involved, while acknowledging my limits and be thoroughly aware of on my own

desires because East Asian societies favor collectivity, systematically

repressing the individual voice. Only then can I gain a perspective, a

subjectivity and gain some persuasive power in my voice. In short, I must

attempt to see only what I want, and nothing else. That is why I believe my two

feet must be inside the frame, and my head must be outside the frame. I think this

is the way I can live life seriously, while making a joke of myself. Taking

responsibility is important, but if I become so serious and so important that I

cannot mock myself, I will then be an irritating asshole.

Mun: Let’s now move on to the

work 1.6 SEC (2016). In that it comments on

the essential structure of video, including camera, viewers, space and

screen, 1.6 SEC is the work that is

directly connected to your new work Mirror Organs.

The overwhelming impression/keyword in this work is the machine vision. Channel

1 shows the movement of a machine assembling a car, while channel 2 shows the

movement of the camera filming the machine. Here the movement of the camera

imitates exactly the movement of the machine on the assembly line, and since

the camera is also a machine, both channels represent the viewpoints of

machines. The key element that provides the heterogeneity of the machine

vision, not human vision, is the camera work. The movement of the camera,

causing the screen plane to turn upside-down, swirl and rotate, as in some

scenes of Channel 2 of the machine watching the painting on the wall, presents

an unfamiliarity. How did you specifically set up the camera work?

Park: The movement of the camera

is an exact imitation of the movement of a machine on the assembly line.

Originally I wanted to attach a camera to the robot arm on the assembly line,

but because of safety issues this was not possible, and I had to film the

motion separately. I borrowed motion control gear, attached the camera and

moved it by remote control. Since one had to film the robot arm and one had to

film the camera filming it, I mounted two cameras on the motion control gear.

Assuming that channel 1 was the viewpoint of the machine, and channel 2 was the

viewpoint of the camera, I edited the footage so that channel 1 would gradually

become distant, and channel 2 would gradually become closer. In realizing the

rotating camera work, I used the Dutch roll technique, which is an effect of

taking away gravity by rotating the Z axis based on the picture. I also used

Jimmy Jib shots to ascend along axis Y, and tracking shots to move

horizontally. By using a lot of techniques to move the camera itself, I tried

to visualize the vision of the moving robot.

Mun: In this work the camera

movement seems dazzling at first, but is in fact simpler than one may think. It

consists mostly of rotation movement. To give the machine’s view a sense of

difference, you could have further emphasized the discontinuity through speed,

zoom, the sense of cutting off in editing, etc. Was there a reason for

simplifying the camera technique?

Park: I thought the method of

using fancy camera work had already been used a lot in commercial films, and

had therefore become cliché. Though the video image appears to flow along

plainly without fluctuation in dynamics, this is actually a trick. In some

cases I normalize the speed by making fast-moving objects look like they were

moving slowly and vice versa. For example, the movement of the robot arm in the

beginning of the video, which appears to be moving slowly, was filmed at a high

speed of 120 frames per second, and projected at normal speed to make it look

slow. I manipulated it to appear slow because I wanted to give the feeling of

it going into motion gradually, as if a person stretches his arms right after

waking up. There are some parts besides this where I made the motion seem slow,

such as the part with the clock and the part with a person appearing. In the

case of the clock scene, I manipulated it to play in reverse. Showing human

beings, I altered the speed because I imagined that from the machine’s point of

view, the movement of human beings would appear slow and delayed.

Mun: Showing the clock in slow

motion seemed like you were emphasizing the flow of time. The concept of time

seems very important in this work. Let us talk some more about the difference

between actual speed and the apparent speed you just explained.

Park: I wanted to make a

structure that looked like it was moving at a steady rhythm, but actually had

mechanisms of different rhythms: accelerating or decelerating in a whirling

motion embodied in a flat, linear velocity. Since people need a commonly agreed

time in order to carry out social life, they inevitably go along with the

mechanical time. But people are biological beings, and therefore have their own

biological times. When there is discord between these two kinds of time,

conflict and various emotions occur. For example, if you have a deadline but

your physical condition can’t manage to follow it, you feel anxiety or

frustration.

Mun: The idea of non-linear and

heterogeneous temporality is important. The structure of time you just

explained would be easier to understand if we picture the concept of

longitudinal waves—like when you push a spring back and forth, the force of the

push is transmitted in different densities through the spring. Though the

energy is transmitted as the dense and the loose parts appear in alternation,

because the direction of the waves and the direction of vibration in the medium

are parallel, there seems to be no movement on the surface. Such an image could

appropriately illustrate the structure where times that appear to have constant

speed, but in fact have different rhythms, coexist. Meanwhile, the concepts of

mechanical time and biological time seem to require additional explanation. Let

us talk some more about your intentions in planning your work, and the

relationship between time and emotion.

Park: This work was produced as

part of the “Brilliant Memories” project hosted by Hyundai Motors. The Hyundai

Motors assembly plant has already been automated and is operated based on

machines rather than on humans. While looking at the machines, which can be

seen as the actual subjects of the factory, I thought about humans’ time and

robots’ time. Because sensations are felt through time, and human time and

robot time are different, the sensibilities of robots would be completely

different from those of humans. Human emotions begin from sensory perception,

and since sensation requires time, emotions are inseparable from time. That is

to say, time is the form of emotion.

Mun: Though people with different

biorhythms must match themselves with mechanical time in order to live in

society, under the surface we can find the coexistence of different rhythms

unique to the individual. The emotions humans feel are also time-dependent in

principle, and occur in the gaps between mechanical time and biological time.

This could be summarization of your intention. But I doubt whether it is

fundamentally possible to divide humans’ time from robots’ time. I think the

time of machines is already melted in the sense of human time, and though there

may be some relative difference, it would be difficult to divide the two

fundamentally. As you mentioned, our social time is based on mechanical time,

and our bodies have already been tamed to the standardized and segmented nature

of such time. Moreover, as technical civilization develops, we become more

surrounded by machines, thus causing our senses to become increasingly more

mechanized. This is easily understandable if we think about our lives before

and after the use of smart phones and computers. While novelists of the past

developed their thoughts through handwriting, the ideas of today’s novelists

begin to flow only after they turn on their laptops. Since your senses and

views as an artist have been tamed by the camera, it is only proper to say that

your vision also includes a mixture of the machine’s vision and the human’s

vision. I believe machines’ time has been implanted in humans’ time per se,

which has already become so hybridized that the two cannot be separated.

Park: I certainly agree. What I

wanted to express in 1.6 SEC was also the

suspicion of the dichotomous division between humans and machines. While

looking at the lively movements of the robot, I felt a strange sense of

identification, and my contemplation on where this feeling came from became the

starting point of the work. If we were to say the main factor in

differentiating between humans and robots is emotions, which in fact are

necessary in communicating with and relating to others, then, emotion is not a

property unique to an individual, but a social composition. There was a

conflict between the company and the labor union because the company wanted to

accelerate robots by 1.6 seconds to improve production timeline. If the speed

of production by robots in an automobile plant is accelerated by 1.6 seconds,

this is not a problem for machines, but for workers. While machines can

immediately adapt organically to the change in the production environment,

workers who are already accustomed to the existing rhythm had difficulties

adapting to this change. Perhaps that is why I thought that in the car plant

the machines seemed more alive than the humans. But when I thought about the

reason behind my bias, it was because my viewpoint was already in fact that of

the camera, the machine.

Mun: The issue of robots and

humans is repeated in your new work in the form of model guns. Let us return to

this issue later, and go on to that of the video’s structure. As I watched the

movement of the camera in 1.6 SEC, I personally

recalled La Region Centrale (1971) by

Michael Snow. In the case of La Region Centrale, the movement of

the camera was not segmented but continuous, which allowed the spectators to

follow the movement of the camera and become united with it. In other words,

the spectators’ eyes were positioned exactly at the “empty center”(position of

the camera), which is not shown in the video. Meanwhile, in the case of 1.6

SEC, the movement is continuously cut by editing, making it

impossible for spectators to have a single, continuous, united perspective.

Furthermore, since it is two channels that cannot be seen at a single glance,

the discontinuity, or dizziness of disorientation, is further strengthened. Let

us talk about the relationship between the viewers and the camera in 1.6

SEC.

Park: Since I was trying to

embody the sense(vision) of the machine, and express this through a skin of

mechanical time (but actually a complex time in which times of different strata

are entangled), I naturally thought the cuts had to be made. In fact, I tried

to visualize the cuts more vividly by reinforcing the editing. Since the

machine itself is segmented, I tried to bring out the feeling of segmentation

in the video as well.

Mun: As I mentioned earlier,

in 1.6 SEC, the camera is equivalent to the

machine in the assembly line. Since the view of the artist is equivalent to the

view of the camera, the equation of Camera = Machine leads to Director = Camera

= Machine. In the case of Snow’s La Region Centrale, the camera

becomes the viewer because the camera is not shown. In 1.6 SEC,

however, the camera is shown, and the viewer becomes an outsider. But an

interesting point is that the spectator, who has become an outsider, again

becomes an insider due to the installation of two channels. The spectator,

surrounded by machines filling the screens, becomes a gadget locked in the

machine in the assembly line. The entire installation (including sound and

image) become a machine that ascends and descends regularly.

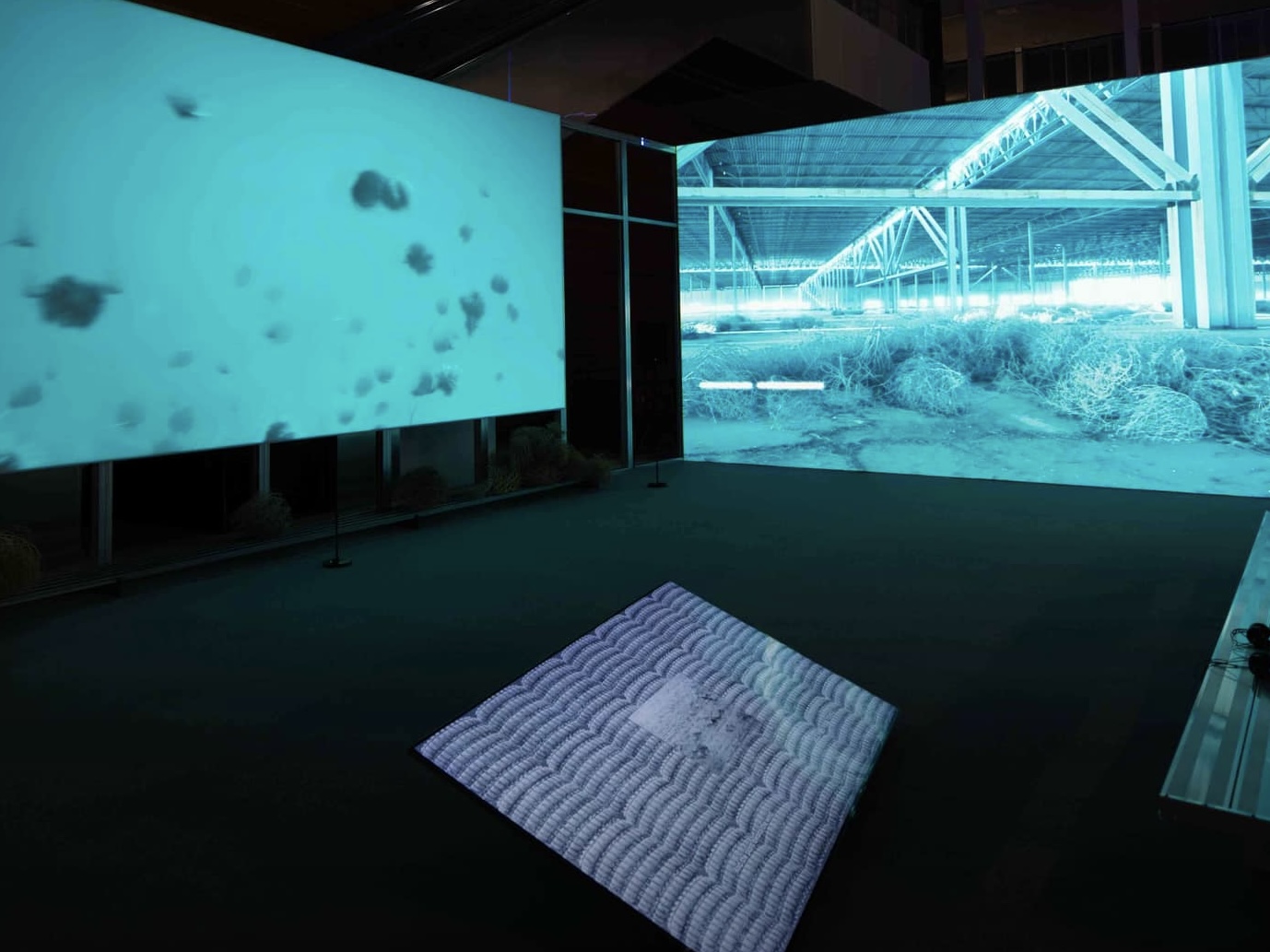

Park: Since I composed channel 1

as a scene filmed by a camera (movement of the machine), and channel 2 as the

camera filming that, with channels 1 and 2 installed to face each other, the

viewer will naturally be positioned between the two screens. Here the

installation space becomes the interior of the camera. That is because the body

of the camera exists between the camera lens and the scene. Therefore, the

spectator finds him/herself inside the camera.

Mun: Though this may seem

far-fetched, I wonder what it would feel like if this work were viewed in a 4DX

theater. I am curious how the feeling of disorientation would change. Of course

I know this is an absurd idea.

Park: Since it was not taken with

a miniature camera, sense of scale would be off.

Mun: You take my joke too

seriously (laughs). Finally, I would like to talk about the

non-sync, which in my opinion is the greatest charm of 1.6 SEC in

terms of structure. The two channels of 1.6 SEC are

of different lengths. Channel 1 is 16 minutes and 25 seconds, while channel 2

is 12 minutes and 20 seconds. Moreover, I understand that the sound was also

produced separately. Because the videos of the two channels and the sound are

all independent and different in duration, each combination of image 1—image

2—sound will be different every time. (In reality, no viewer can see the same

video.) Is this composition, which is a kind of random combination, an attempt

to escape from the classical film structure, in which the length and

composition of the film are fixed?

Park: You could say so, but

rather than being conscious of paragons, I wanted to make a different

structure. Simply, I thought there was no need to match the sync because one

would not be able to see the two channels facing one another at once anyway, and

I thought it would be good if the combination continuously changed. It felt

visually more effective to generate new combinations through the continuous

incongruity. I wanted unexpected and unintended things to happen in the

collisions between image and image, image and sound. Through this method I

ultimately wanted to create a different structure, which was a pattern but also

not a pattern.

Mun: The form of pattern that is

not a pattern coincides with the compound time concept we discussed earlier—the

compound structure in which mechanical time and organic (biological) time are

interlocked. Formally and conceptually, you seem to like flexible structures.

Haven’t the aspects of spontaneity and unpredictability increased in your

latest work Mirror Organs? Since the transition of the pictures is

activated by sound exceeding a certain level of decibels, spectators stomping

or sudden actions can trigger transition of the scenes, in addition to the

pre-planned sounds. What kind of image will appear in the next scene on the

screen is also semi-automatic, as it is a matter of probability.

Park: With the exception of A

Dream of Iron, in which the images of each channel must be symmetrical, I

did not match the syncs in the other multi-channel works. In Cheonggyecheon

Medley also, the lengths of all five channels are different.

As the planets in the solar system each have different orbits and encounter one

another at different times, the time difference given to each channel as it is

repeated results in a different combination every time. Such combinations are

not intentional, but may seem to spectators as if they were planned. What I

consider important are the asymmetry and polyrhythms created by the combining

of images. In my new work, I further strengthened the aspect of spontaneity in

comparison to 1.6 SEC. While the order of

scenes—which image would come after which—were decided in 1.6

SEC, in the new work, editing cuts are decided by the robots (and

the sounds made as they move). The robot’s movements and the transition of

scene caused by such movements, however, are also decided by a program. (The

movements of the robot are wired with an analogue circuit, and the transition

of scenes is assigned within the probability set by the program code.) Such

non-intentional editing may seem random at first, but is in fact a reinforcement

of my intention. That is because I have complete control over the chance

proportions of picture transition. I do like unexpected discoveries, but I also

hate disorder.

Mun: Let’s now come back to the

issue of robots and humans. Your new work Mirror Organs applied and

expanded the combination of drama and video, which you had experimented with

in Stairway to Heaven. While this work is a

gigantic cinematic feedback loop space on one hand, it can also be seen as a

huge theatric stage using the video as lighting on the other. The actors

in Stairway to Heaven were replaced

with robots. The keyword “robot” has been used from time to time as subject

matter or concept in your works, such as 1.6 SEC,

but never did you embody robots physically on such a large scale. This seems to

be your first time to materialize moving objects full scale. Were there any

particular difficulties in realizing this?

Park: First of all, I didn’t have

the budget to hire actors for the entire duration of the exhibition (laughs). I

chose robots because I thought they were easier to control. I was completely

wrong. Having to manage mechanical and structural design and to program the

movements of the robots was a big problem. I suddenly had to install an

engineer’s brain in my head. The difficulty was to give robots sharp,

disciplined motions. The beginnings and ends of their movements had to be clean

and graceful like those of well-trained honor guard, but it was not easy to

embody this mechanically. Because of inertia occurring in the direction of

movement, there would be recoil when they stopped. Such error is caused by a

combination of numerous variables, including budget, equipment, velocity and

inertia. I had to create the movement I wanted with the equipment possible

within a limited budget. I solved the recoil problem by adjusting the speed of

the robots and using the friction of plastic parts. Meanwhile, I also had to

consider possible malfunctions during the long exhibition period. For such

reasons, I chose an analog system, rather than digital. In the event of

malfunction, a digital system would stop completely, while in an analog system

only one robot would stop functioning.

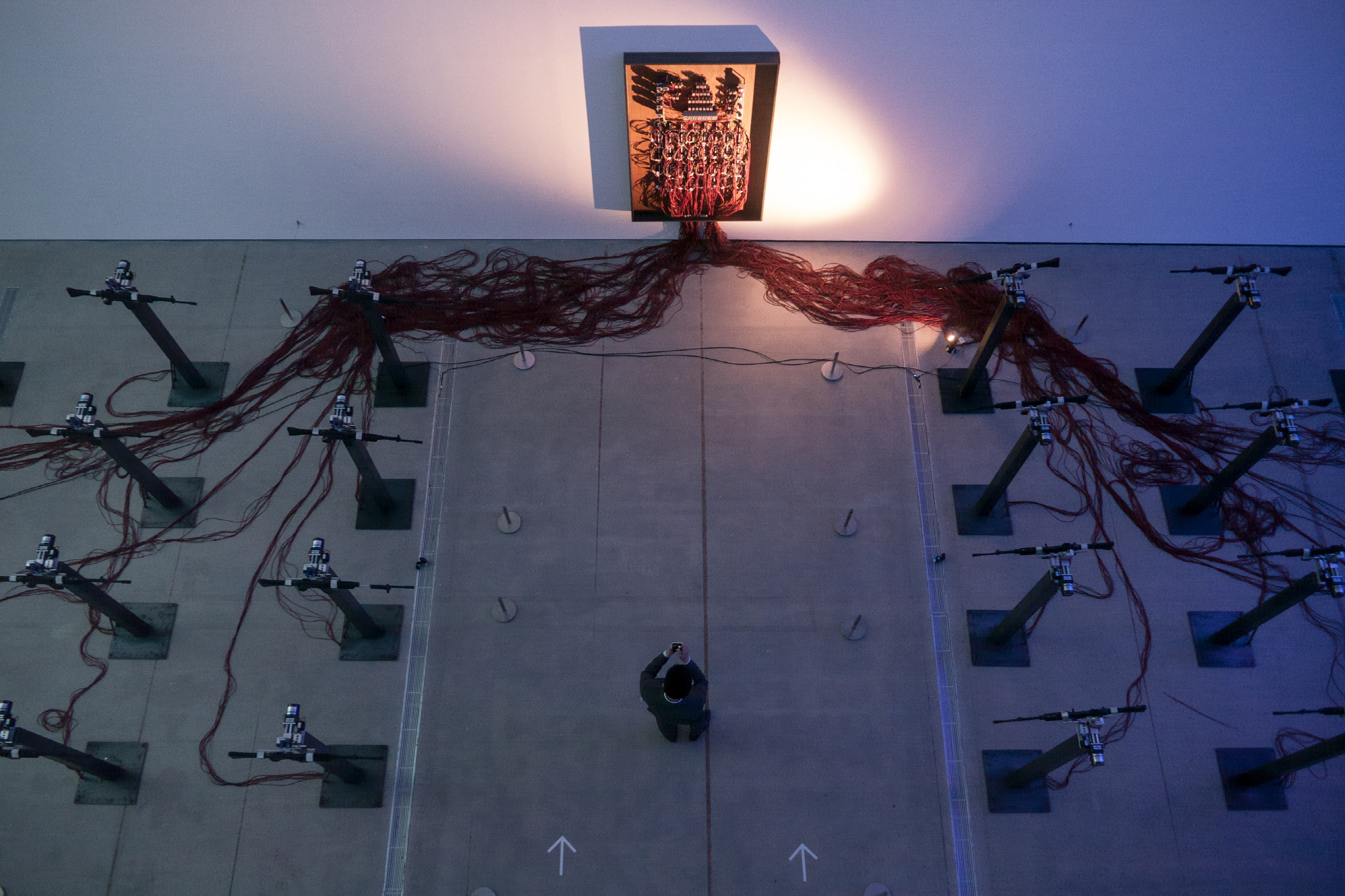

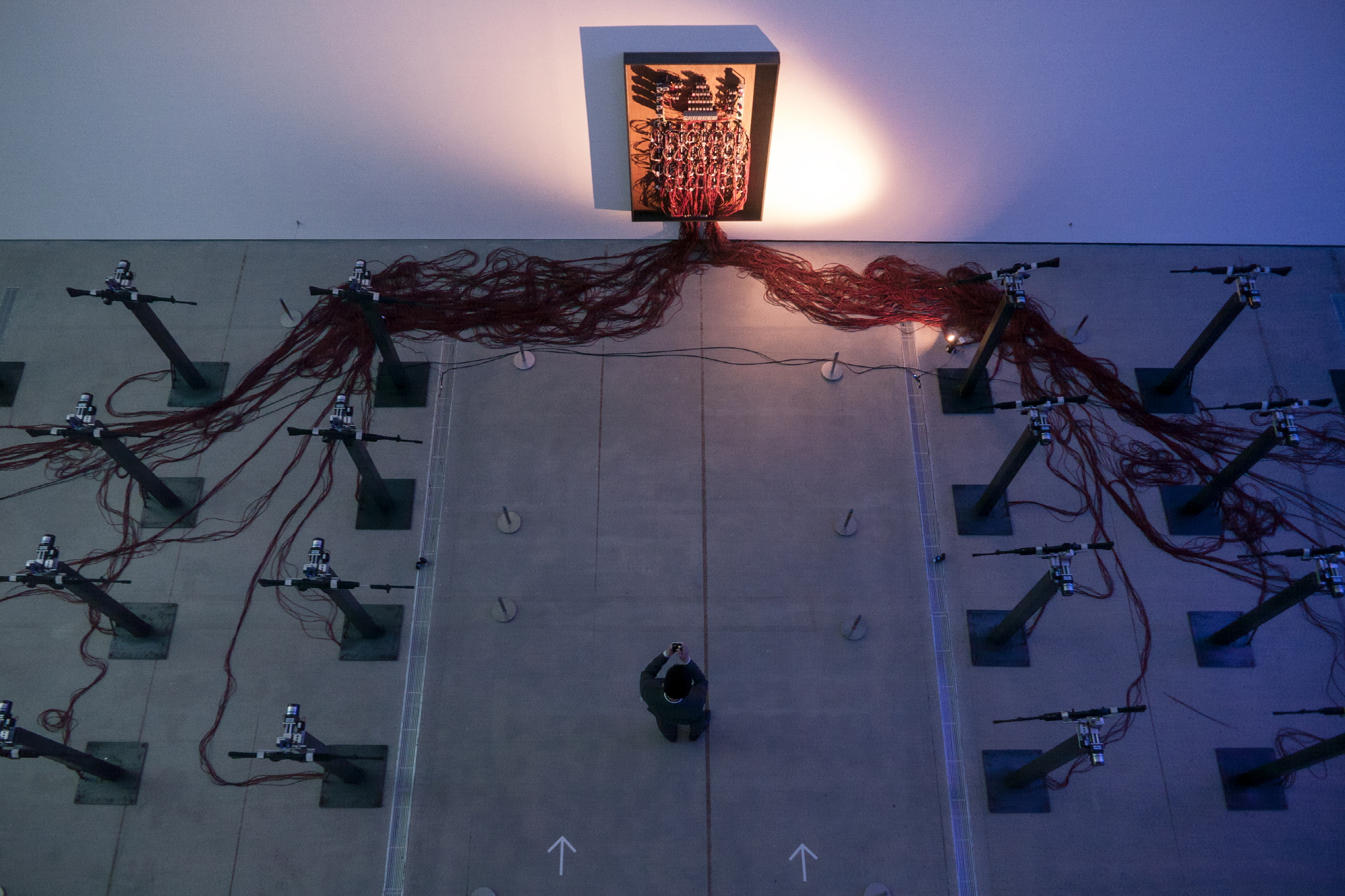

Mun: In Mirror

Organs, the robots (model guns) placed between the video screens

evoke the young men (humans) featured in Army.

Here the robot actually visualizes the gaze of the machine (camera)—as the

aimed gun symbolizes the gaze of the camera, which is looking in the same

direction, the spectators standing between guns pointed at them from both sides

can feel the presence of the two-way gaze with their bodies—but on the other

hand, it also serves as an analogy for the condition of the individual, who

lives as part of a group. In that sense, Mirror Organs can

be linked conceptually to Army.

Park: That is exactly what the

military does to an individual. It makes robots, and turns individuals with

different characteristics into parts of a collective. I sometimes feel that I

am like a malfunctioning robot. Robots work only according to what has been fed

to them, unable to think on their own. We are like malfunctioning robots, which

don’t work when they are required but work only when they are not needed. The

movements of the robots were designed in emulation of honor guard ceremonies,

or various kinds of training conducted in the military. The training is

repeated until all constituents are completely synchronized. As they repeat

only the salute motion for four to five hours, the individuals are reborn as

parts of the group.

Mun: I understood your

explanation to mean that the masculinity of Korean men is not biological but

rather something composed socially within the male group, and there is

collectivism behind that mechanism. To say that someone is not an individual

but part of a group is to say that he is unable to act subjectively, and that

his standards of determination are outside. (This question is also raised

in Stairway to Heaven.) Moving on to the

structure or mechanism of masculinity here would be deviating too much from the

topic of discussion. After all, your new work Mirror Organs does

not deal with masculinity as deeply as Army. But I do have to ask

this question. As a Korean man, what is your position on the masculinity of

Korea, which reduces the individual to one of the group? Is it fear,

captivation, or both?

Park: Fear and captivation both

exist. Being subjugated to a group and my disappearing, losing the ability to

make my own judgments, becoming what I consider to be a problem…this is

frightening. When I witnessed someone being stomped on in boot camp I pledged

to myself that I would never be that kind of superior. But when I later became

a squad leader, and one of the soldiers ignored my directions during training,

I grabbed him by the collar, threw him down on the ground and stomped on him in

an attempt to intimidate him. As I yelled at him, I felt this infinite fear. In

a course of two years, I had become the same kind of person without even

realizing it. In retrospect, the reason for such fear may be a desire to become

someone better than “them,” more “noble” than them. Meanwhile, the attraction

can be interpreted as a kind of sense of belonging, which is in fact extremely

effective. There is also the aesthetic pleasantness.

Mun: I understand the

effectiveness, but what is the aesthetic pleasantness? Are you referring to the

pleasure when one witnesses the complete synchronization in a mass game? Isn’t

that a pleasure of someone looking at it from the outside, rather than the

performer himself?

Park: Of course. The attraction I

speak of is not the urge to become part of it but the desire to create a frame

and observe it. Perhaps this is my identity as an artist. Because I am not free

to escape from it at my own will, I imagine making a frame and getting away

from it, while I observe from the outside.

Mun: You seem to be talking about

the attitude you mentioned earlier—neither being completely immersed, nor

completely being a bystander (or either being completely immersed or completely

ignoring). Perhaps the creation of such an ambivalent state is the central

motive penetrating your entire body of work. Finally, I want to conclude our

talk with a discussion about materiality. Though you started out with

filmmaking, the proportion of installation seems to be gradually increasing in

your work. Is it that you felt a limitation in the non-materiality of video?

Why is physical property important to you?

Park: In short, I think the

senses felt by the body are important. Video images can show tactility, which

is of greater importance in better images. But digital video is an indirect

sense mediated visually, and it lacks direct physicality. Video images can be

rewound and played indefinitely, but with real objects, which are restrained by

gravity and materiality, and manifest a one-off, finite nature, there is no

turning back.