Utilizing video as his primary media, Kelvin Kyungkun Park has

perceptively traced the entanglements between Korea’s industrialization process

and various elements and ideas related to pre-modernity and modernity. In Cheonggyecheon

Medley (2010), Park explored the small metal-working shops and

factories clustered around Cheonggyecheon Stream in Seoul, as well as the

people there. In A Dream of Iron (2014), he used

iron as his context for two of the dominant symbols of Korea’s

industrialization: Posco (a steel-making company) and Hyundai Heavy Industries.

Initially inspired by ancient drawings of whales from the Bangudae Petroglyphs,

which he thought resembled modern-day ships, Park investigated these two

massive industrial infrastructures, both of which are located near the Bangudae

Petroglyphs. In addition to exploring his personal emotions, the film also

contemplates the origins of Korean art and myth and considers the role of

cultural ideology in guiding the country’s contemporary history. More recently,

in 1.6 Sec (2016), Park captured the incessant

large-scale production of an enormous car factory through a dynamic play of

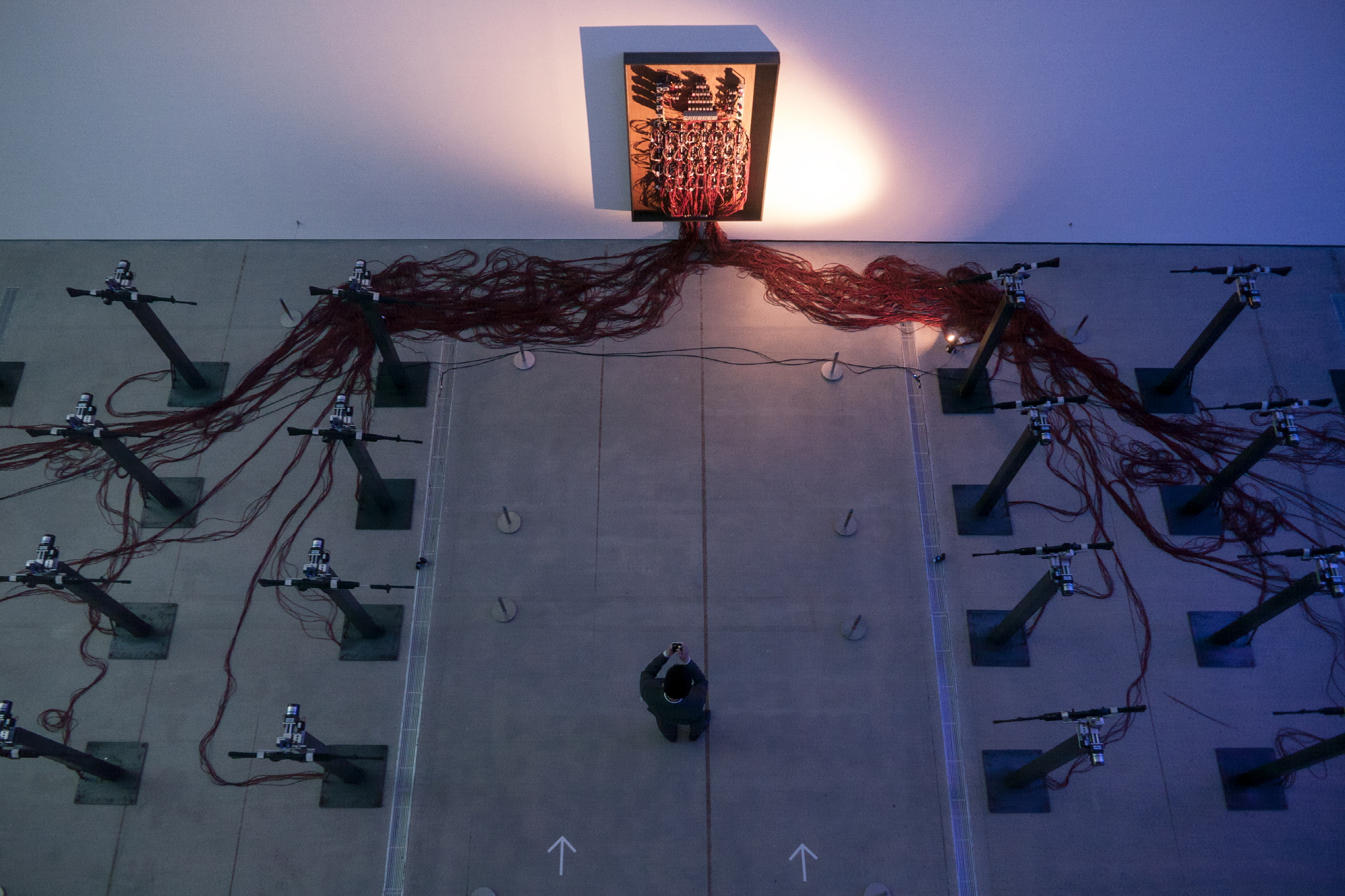

light and air, heightened by the ubiquitous sound of robots. Army:

Portraits of 600,000 (2016) examines how Korean society has been

affected by the army culture experienced by most Korean men, who are subject to

mandatory military service. Notably, in all of these video works, Park

represents the male-centric hegemony of Korean society with a distinct symbol:

iron, cars, and the army. Park uses these elements to unveil the masculinity

embedded in Korean culture, and to reveal the hidden side of his visual

spectacle, in which such culture unfolds.

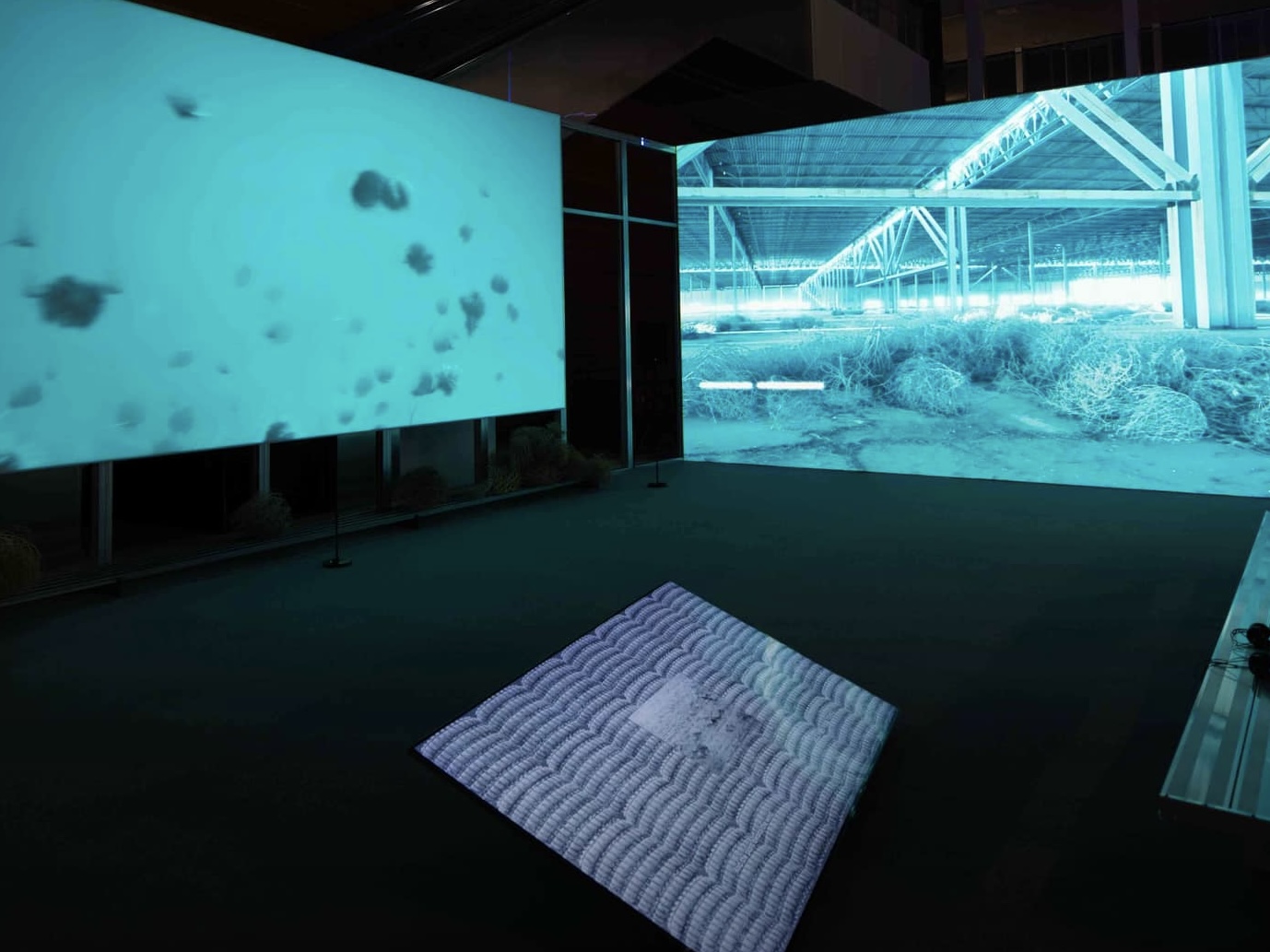

Park’s most recent work again conveys an incisive critique of society but also

demonstrates the evolution of his critical approach. It is a video and

performance work entitled Stairway to Heaven, which most Koreans know as

the title of a hugely popular TV drama from 2003, rather than as the title of

the Led Zeppelin song. This work involved both pre-produced video and real-time

filming of a performance at the opening of an exhibition, using the entire

gallery as a backdrop. Like the drama, Park’s piece involves four major

characters, and he uses performance to explore and classify the ways in which

people form relationships with one another. Emotions experienced during the

process (e.g., passivity and excitement, hesitancy and eagerness, joy and

regret) are expressed through the faces and gestures of four dancers as they

meet, slide by, and depart from one another. Most memorably, a real-time video

of the live performance was juxtaposed with a previously filmed video that was

projected on the walls of the gallery, thereby disrupting the audience’s

perception of both time and space. Furthermore, two different videos were

projected onto the walls: one video that had been previously shot, and one

video that captured the “real-time” events happening in the gallery (including

the projected video). Notably, Park used the exact same camera angle and set-up

for both videos, thus creating a mirroring effect that made it impossible for

the audience to perceive the subtle time gap between the two projected videos.

The resulting work combines synchronization and asynchronization in the same

space, so that the moment that has just happened, the moment that is now

happening, and the moment that is about to happen are merged in the same video

frame. By visually emphasizing the synchronization, Park actually evinces the

asynchronous and segmented time that usually cannot be perceived with the naked

eye. In his video, time is segmented, repeated, and mixed; continuity

continually gives way to segmentation, and vice versa, as if a digital clock

has been hung in the performance space. Park’s visualization of the spatial and

temporal gap enables Einstein’s synchronization and asynchronization to coexist

on the same screen. Such segmentation might also represent the dislocated and

disintegrating relationship among the performers in the video.

Being set in a digitized time and space, this segmented relationship hovers

around the past, present, and future, eventually eliminating the division

between here and there, and between that moment and this moment. The critical

approach of Stairway to Heaven echoes another of

his earlier works, entitled Spatio-temporal Machine (2015).

Both of these works demonstrate how Park, who started out as a documentary

filmmaker, has begun to integrate elements of film and art, producing his

unique works in parallel with these two fields.