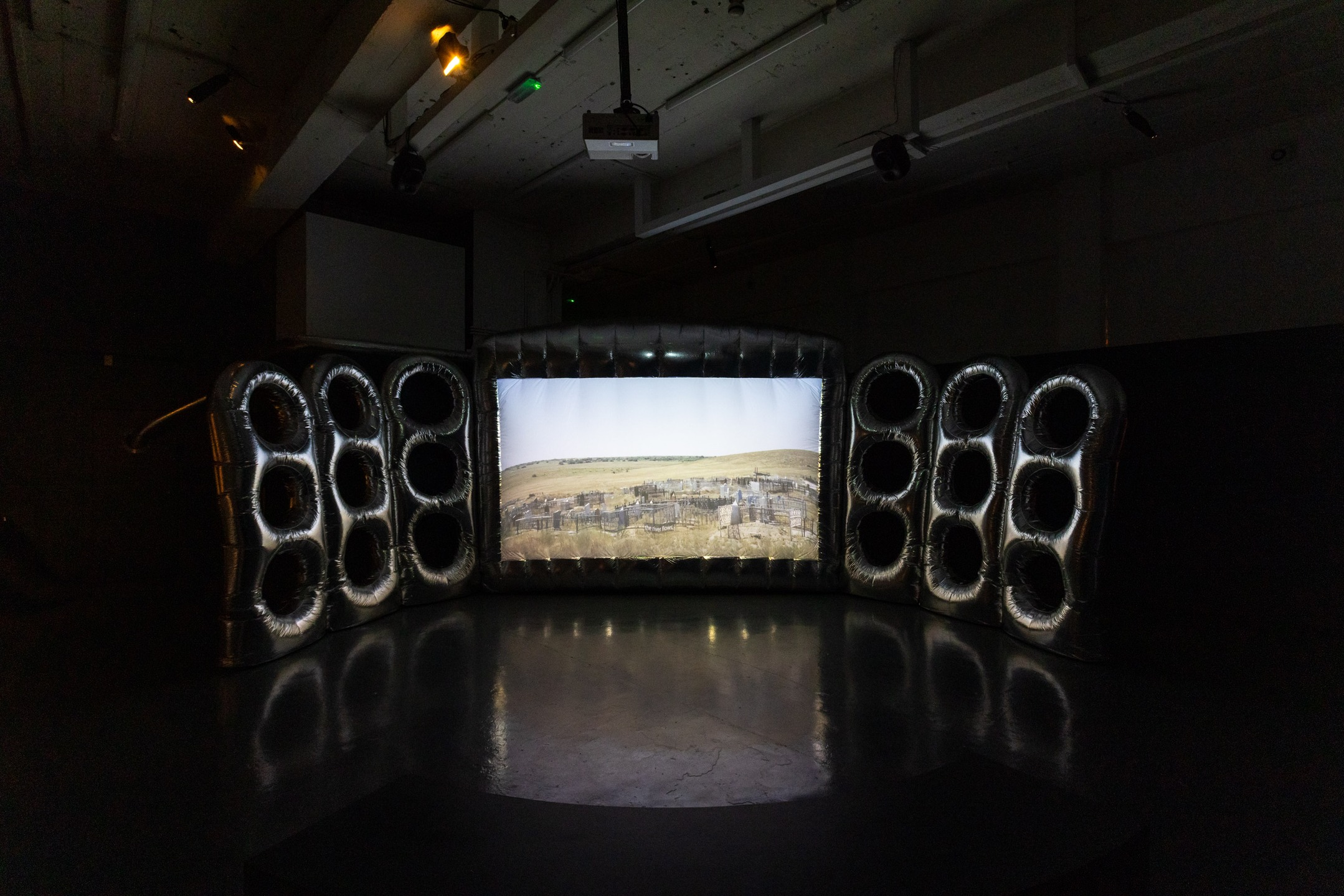

“Overtone”

is the title of Sojung Jun's first solo exhibition and her new three-channel

video (2023). It is a musical terminology that describes the harmonic series

that collide and blend around and above a fundamental note to create a coherent

musical tone. The term is closely related to the overtonal

montage’ coined by Sergei Eisenstein (1898-1948), a film director who

left behind many studies on Soviet montage forms and experiments.

Explaining overtonal montage using the principles

of music, Eisenstein noted that primary artistic elements work together with

various secondary components to create a dominant impression or unity.

Therefore, he argued that overtonal montage not

only evokes a consonant atmosphere or feeling but also elicits physical

perception; it triggers a holistic experience, including emotional and physical

reactions. Thus, Sojung Jun’s Overtone enables an immersive

experience of multiple sensations through time and space as harmony is found

within the dissonance between the instruments of Korea, China, and Japan.

Probing

into Sojung Jun’s ongoing investigation of ‘sound,’ the artist

launches syncope for the first time, an AR application developed

especially for her first solo exhibition for Barakat Contemporary as an

extension of the new film presented at the National Museum of Modern and

Contemporary Art (MMCA), Seoul for the 《Korea Artist Prize 2023》. Featuring a new

series of sculptures entitled Epiphyllum I (2023)

and Epiphyllum III (2023) along with the new

three-channel film Overtone, Jun proposes an

interesting perspective that enables an organic web of relationships between

sculptures, video, and digital data that transcends time and space, and the

real and virtual.

Amidst

the rapidly changing pace of modern capitalism, there are still those who are

creating a new world in their own ways. For instance, Sojung Jun has been

asking, “Can video really shed light upon the invisible? Can it render the

invisible visible or audible?” In this context, it was important for the artist

to evoke all types of sensations besides the visual sensation. Through the

newly presented three-channel video work, Overtone, she attempts to “trace

‘tangible/physical sound’ and ‘tone’ within the narratives and solidarity of

Asian women by overlapping them with the speed of bodies, plants, language, and

data that cross borders.”

In

preparation for the exhibition, Jun often spoke of the characters, Snow Woman

and Princess Bari, who appear in Kim Hyesoon’s I Do Woman Animal

Asia (2019). Princess Bari, a mythical woman who took it upon

herself to guide the dead between this world and the afterlife, created an

evolving and ‘ever-becoming’ identity by constructing a visible world

within an invisible world. Like the Snow Woman and Princess Bari who constantly

alter and expand their identities, the artist seeks after sound to discover

countless matters that abide in this world without hierarchy and unknown

origins.

Jun’s

new film, Overtone, revolves around the journey of Soon

A Park, a gayageum player who has traveled across North and South Korea tracing

sound. For the production of the new film, three composers from Korea, Germany,

and Guatemala collaborated to compose three songs, with predetermined length

and tempo each for gayageum, koto, and guzheng, which are performed in unison

by KOTOHIME, the Korean-Chinese-Japanese zither ensemble. This long

journey in which three composers and three performers connect and communicate

in different places to create music captures the materiality of sound and tone

that pass through the three countries under the large theme of Crossing

Borders, which comes to an end with a video of their performance done in

unison. The process is akin to experiencing harmonious counterpoint through

sound.

Composed

of three main parts, Overtone begins with a solo

performance by Nobuko, the Japanese koto player on the theme of “Melodies

of Transit”, followed by the Korean North Korean gayageum player’s solo

performance on the theme of “between” or “traveling”. Finally,

the video ends with a solo performance by Xiaoqing, the Chinese guzheng player

performing on the theme of “wave”. In this sequence, the audience can

appreciate the differences in techniques, tone, range, and sound between the

Korean, Chinese, and Japanese qín (琴) instruments. Their performances were filmed using a long-shot

camera technique.

In

the second part, the three performers sit apart from each other in a triangular

configuration and have in-depth conversations about the structure of each

instrument, the tools they use, and their techniques to arrive at

a harmonic performance. An interesting point in their conversation

about the music to be performed is not only found in the differences between

the three instruments, koto (13 strings), North Korean gayageum (21 strings),

and guzheng (21 strings), but also the interaction between the performers as

they share their concerns on improvising with the cultural elements of the

Korean, Chinese, and Japanese musical traditions embedded into each song under

the composer's guidelines.

For

example, they include instructions such as “use the

Korean nonghyeon (弄絃) technique,”

which is not used for the Japanese instrument koto, or “play the North Korean

gayageum (21 cash) with a pick in certain parts,” when it is not originally

played with a pick. For playing the Chinese guzheng which has traditionally

been played to make resonating sounds, they included instructions such as “use

the muting technique commonly used with gayageum.” Through discussions like the

above, the players practice the first, second, and third movements to slowly

find harmony in the dissonance, incorporating experimental elements that

reflect different musical elements. Moreover, Jun’s interest in

the appropriation of media is exposed especially in this part of the

film.

What

is particularly interesting about their conversation is the techniques and

tools they use for their performances are different. The tone varies depending

on multiple factors such as the materials and shapes of the pick, the angle of

pressure on each string, whether one plays bare-handed, the thickness of the

string, and the method of handling body weight and gravity onto the

instruments; all of these factors demonstrate the materiality of sound.

Communicating these differences, performers work together as an ensemble

through a laborious process of fine-tuning and learning with each other.

In

the last part of the video, a scene of improvisation over a long, slow period

is shot through a super-telephoto lens. Jun uses close-up shots to not only

capture the sounds but also the performers who pluck, rub, and press the

strings, the friction between their hands and the strings that intermittently

pause, as well as the sheet music and the hand that turns it, showing the

materiality of the “instrument - hand” _as an extension of the body and the

physical properties of the instruments, evoking an intense sensory collision.

In this sense, sound is not only an audiovisual experience but also one that

accentuates the material senses, its vibration, and the movements of the

bodies. Performers remain silent for some parts of the music, change the

dynamic, add or omit things to make the other performer shine and create a

sound that even they cannot predict from the given song, the creative

substance. Perhaps the medium of heterogeneous and fragmented dissonant sound

was captured through the camera lens, and the artist intended to follow the

movement of the sound and lingering reverberation not even on the score and to

reflect the different angles, shooting speeds, and breathing of each performer

and the cinematographer. This is the moment when complete medium appropriation

occurs via sound. Overtone, which unfolds in “long shot - medium shot -

close-up shot,” _brings a strong immersive experience toward the climax of the

performance through gradual development in its filming techniques.

“In

Japan, there is the word ‘AUM (_阿吽)_:_ _breath of beginning and end of all things,’ _and I felt

something like that. If we can create a world beyond borders within that

breath, the next world… I felt something really profound like that, believing

that could be possible. ”7 In its own way, Overtone creates a new world through

sound.

In

the intermission of the video Overtone, one can find a clasp

between shots that is somewhat different from the previous chapter. This change

is because, contrary to the slow, long-winded sounds of traditional

instruments, the landscapes of modern cities and forests pass by at high speed

while heterogeneous “human-plant 3D sculptures called Epiphyllum” appear

overlapping in different spaces. At first glance, they all seem unrelated such

as accelerated technological advancements and the resulting changes in human

life, the movement of humans, plants, data, and sound. But they are the

subjects of change and movement, whether voluntarily or not. The “human-plant

sculpture” created by the artist is a being with an identity that is capable of

transformation, making its body unrealistically large or extremely small. These

virtual sculptures that can move quickly are seed data – image cuts that the

artist planted in the AR application, Syncopy, as the data

seed of the sculpture she created in a 3D virtual space.8 Sculptures in the

real world with nomadic identities such as “movement,” “transformation,” and

“transfiguration” allow anyone who downloads the Syncopy

application to enlarge or reduce the size of the sculpture and place it with

their fingers and bodies in their own space.