Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

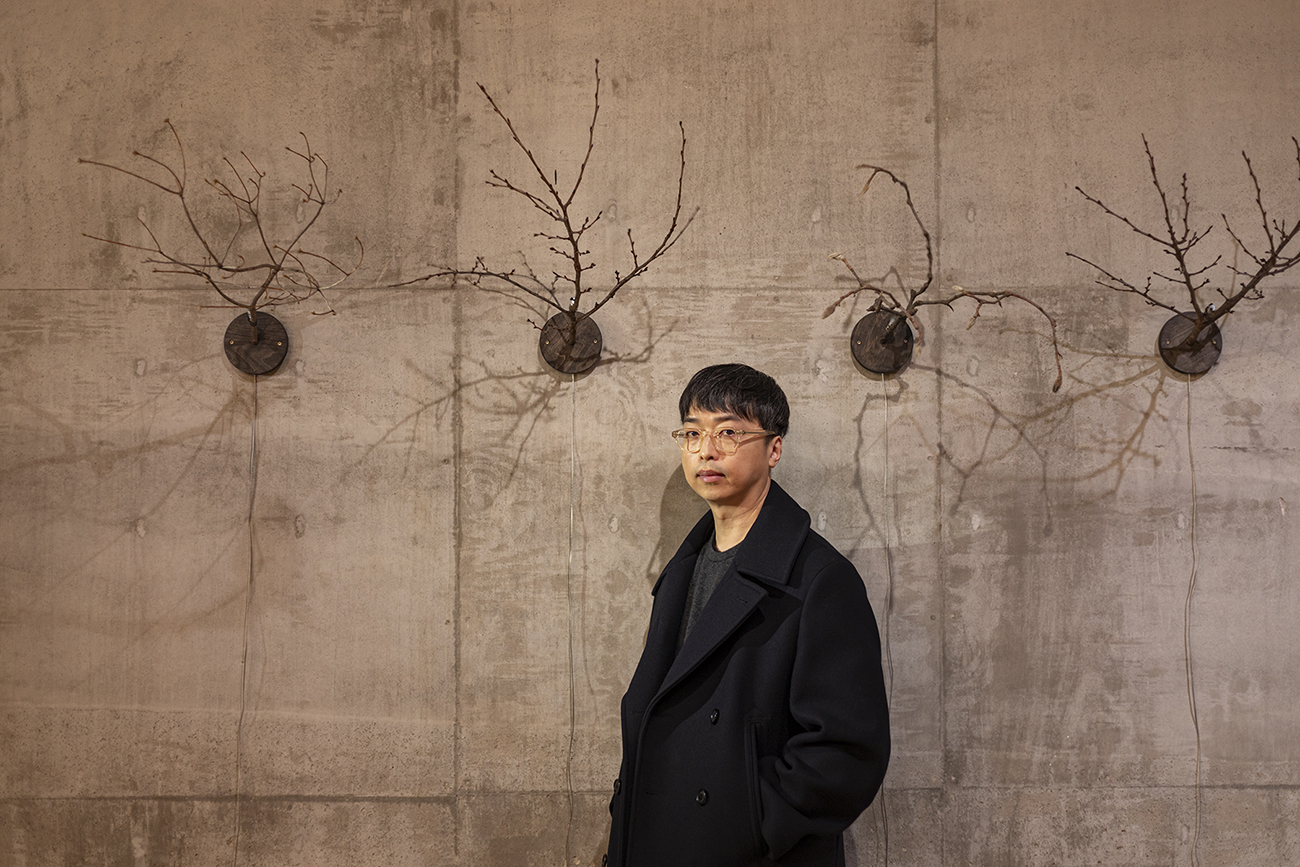

Since 2013, he has held 9 solo exhibitions at venues such as Gonggan Hyung (Seoul, Korea), Oil Tank Culture Park T1 (Seoul, Korea), Space K (Seoul, Korea), Basis (Frankfurt, Germany), and Organ Haus (Chongqing, China). Notable solo exhibitions include 《Ecometropolis》 (2024, Gonggan Hyung, Seoul, Korea), 《The Place of Weeds》 (2021, Oil Tank Culture Park T1, Seoul, Korea), and 《Shadow Labor》 (2018, Organ Haus, Chongqing, China).

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

From 2010

to 2023, Yoo has participated in 16 group exhibitions at institutions including

SongEun (Seoul, Korea), Busan Museum of Contemporary Art (Busan, Korea), Power

Plant (Seoul, Korea), Suwon Museum of Art (Suwon, Korea), DDP (Seoul, Korea),

Seoul Museum of Art Nam-Seoul (Seoul, Korea), Savina Museum of Contemporary Art

(Seoul, Korea), and Sichuan Museum of Contemporary Art (Chongqing, China).

Recent

notable exhibitions include 《Seoul Arts & Tech Festival Unfold X 2024》(2024, Culture Station

Seoul 284, Seoul, Korea), 《RIGHT NOW SEOUL 2024: Global

Contemporary Art Project》 (2024, Hana Bank Place1, Seoul,

Korea), 《Behind the Highlights: Intersecting Scenes》 (2024, Geumcheon Art Factory, Seoul Foundation for Arts and

Culture, Seoul, Korea), 《The 23rd SongEun Art Award

Exhibition》 (2023, SongEun, Seoul, Korea), 《2023 Busan MoCA Platform_Material Collection》 (2023, Busan Museum of Contemporary Art, Busan, Korea), 《Living the Bodies》 (2023, Power Plant,

Seoul, Korea), and 《Whirling, Wallowing~ Bump!》 (2022, Suwon Museum of Art, Suwon, Korea).

Awards (Selected)

Yoo Hwasoo has also been recognized for his achievements with major awards. In 2017, he received the Tomorrow’s Artist Award at Sichuan Fine Arts Institute (Sichuan Museum of Contemporary Art, China). More recently, in 2024, he won the Grand Prize at the 23rd SongEun Art Award (SongEun, Seoul, Korea), further establishing himself as a prominent figure in the Korean contemporary art scene.

Collections (Selected)

Yoo Hwasoo's works are part of the collections of SongEun Art and Cultural Foundation and Seoul Museum of Art.