Prologue. Perfect World: An Afternoon that Gradually Emerged and

Then Gradually Faded Away

It was the last day of a trip. After spending over a month in a

countryside village where I had rested to my heart’s content, had a little fun, and spent ample time reading and

writing amid endless fields of rice paddies and farmland stretched out before

me, that afternoon I thought to myself, Tomorrow, I’ll return home. I rode around the village on a bicycle I

borrowed from the place I was staying. Knowing it was my last day, I found

myself paying keen attention to my surroundings. As if having a long goodbye, I

took everything in while pedaling ever so slowly. A single tree, a tuft of

grass, a discarded chair, a dented sign, a broken streetlamp, a large spider

and its web dangling beside it, moss wedged in the gate of a house, the scent

of the wind licking my skin, the sun setting in a way that highlighted the

silhouettes of the ripened rice paddies…even with

nothing more than those familiar things that had always been there, it felt as

though there was not enough time for me to say goodbye. Just then, a flock of

wild geese began gathering and taking flight. Had you always been

there, too? I wondered. Was it only me who had not

noticed until now? The wild geese quietly folded in their wings

and landed not far from me. They gathered around a puddle full of what appeared

to be shiny black water, lowering their beaks to drink. If it had been

yesterday or the day before yesterday, I might have paused for a moment,

thought to myself, How cute, and moved on. But since I was leaving the

next day, I took the time to watch them a little longer. One by one, raindrops

began to fall into the puddle. The wild geese calmly stood in the rain before

flying off again. Each raindrop that fell into the lonely puddle created

concentric circles, which grew larger and larger before disappearing, only to

be replaced by new ones, repeatedly, over and over. The circles were so

perfectly shaped and the rhythm of each new raindrop breaking the perfection

and forming a new circle so fitting that I parked my bicycle, crouched down at

a distance. A child glanced at me and then approached the puddle. Kneeling

down, she placed both hands on the ground before taking a paper boat from her

pocket and setting it afloat in the puddle. The small boat, neither departing

nor docking, bobbed gently, the paper rustling slightly. Workers carrying

stacked roof tiles on their heads passed by and said something to the child,

who responded with nothing more than a wide smile. When a voice called out from

a distance a moment later, the child turned her head in that direction. This

time, it sounded like a chorus of voices, as if many people were singing

together. It seemed that they were calling for the child, who stood up, dusted

off her hands, and ran toward the voices. I watched her back until she

disappeared from sight. Then I sat there for quite some time, wondering whether

I should take the paper boat with me or leave it where it was.

Recently, I suddenly recalled that long-forgotten day. The paper

boat from that afternoon appeared vividly before my eyes, white and perfectly

clear in my mind’s eye. I was

overcome with a feeling like the one that child might have had when she folded

that paper boat by hand and pulled it out of her pocket. I even felt a little

like the puddle, which had been filled a touch higher than usual thanks to the

rain that had fallen just in time for the child who had run outside to set the

boat afloat. At the same time, I also felt like the house at the end of that

road I was on, which accepted the image of the child, her back to the house, as

she ran toward the voices calling to her, leaving the paper boat behind. The

paper boat carried with it the gaze of a stranger, someone who had spent time

there and who would soon no longer remain, someone who was quietly observing

everything in that place. Even if I had not seen the paper boat that day, it

would not have mattered. Yet because I did see the boat, it felt like I had

spent a perfect day. A series of events that gradually emerged and then slowly

faded away had happened at just the right time on a single afternoon. It was

the ideal last day of a trip. If someone were to ask me what I did on the last

day of my trip, I would have nothing to say other than that I rode a bicycle.

But it was a day where a perfect world—like the

concentric circles spreading out in the puddle—repeatedly

appeared and disappeared.

1. Same/Similar/Alike, Two or Three: The Stories Passed on

One night, I was the last customer to have a meal at a restaurant,

and in the umbrella stand, there was an umbrella that was not mine. At first

glance, it looked like mine—the one I had

brought there—but it was not. The restaurant owner

suggested that I take the umbrella anyway, saying it was the right thing to do

in such heavy rain. And so, awkwardly, I opened the unfamiliar umbrella and

made it home safely. From that moment on, that umbrella lived as if my umbrella

for much longer than my original one ever did, until it, too, eventually left

me. I tend to lose umbrellas easily, but for some reason, I did not lose that

one for a long time. The umbrella was not the only thing that found its way

into my home in such a way. Long ago, lighters often appeared the same way. One

day, I would dig through my bag, and several colorful lighters would rattle

out. My friend’s cat, Pepper, also came into her life

in a similar fashion, and has lived with her ever since. The mushrooms that

occasionally sprout like umbrellas from the pot where my fern is planted are

much the same.

After years of carefully tending to a plant that I received one

time as a gift, I eventually came to repot it. I purposely divided it into two

separate pots before giving one of the plants back to the very friend who had

originally gifted it to me. Over the years, different friends would also give

me plants which I would subsequently repot and give back to them. Some of these

same friends immediately recognized it as the same plant they had once given

me, while others just saw it as another potted plant altogether. Once, while

joking around with a friend, we wondered what it would be like if we were to

receive a child as a gift, raise the child as two separate children, and then

return one as a gift. Our conversation spiraled into something far too problematic

to handle. We touched on issues of individual reproduction, growth, caregiving,

bonds, the identity of gifts and sharing, and bioethics, with our humor

branching endlessly into these topics as if brushing against the farthest ends

of human history. It felt as if our jokes had come full circle and had borne

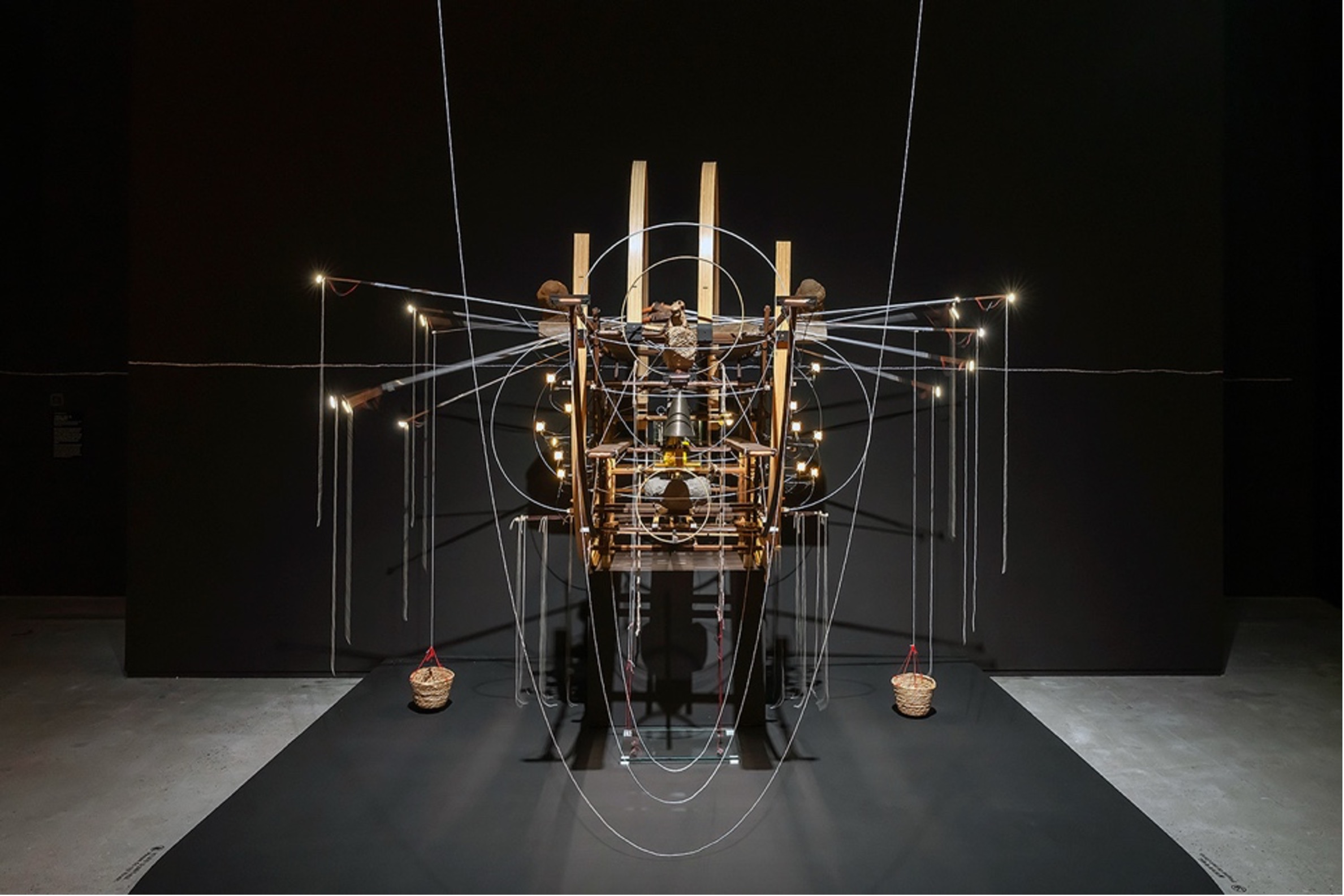

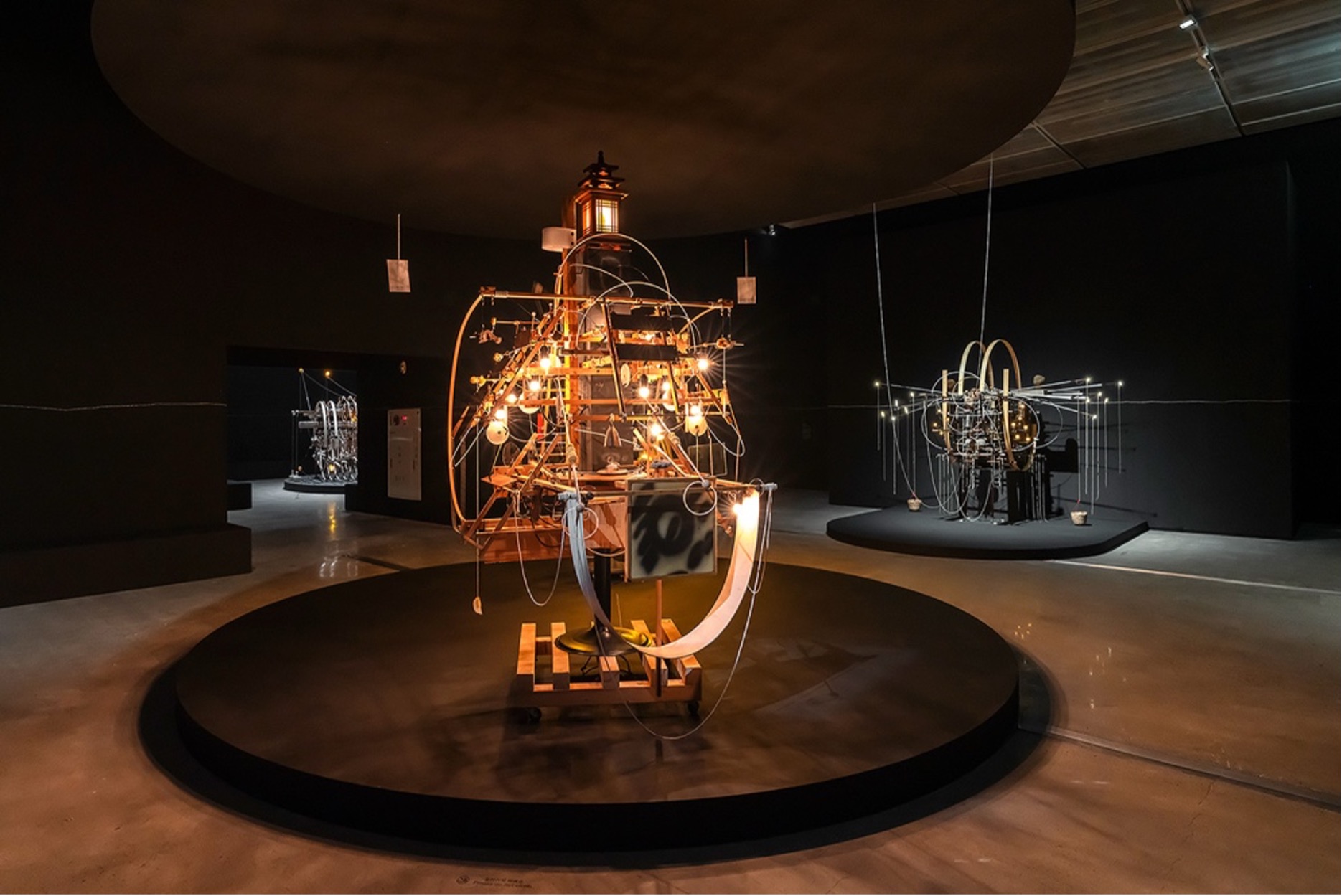

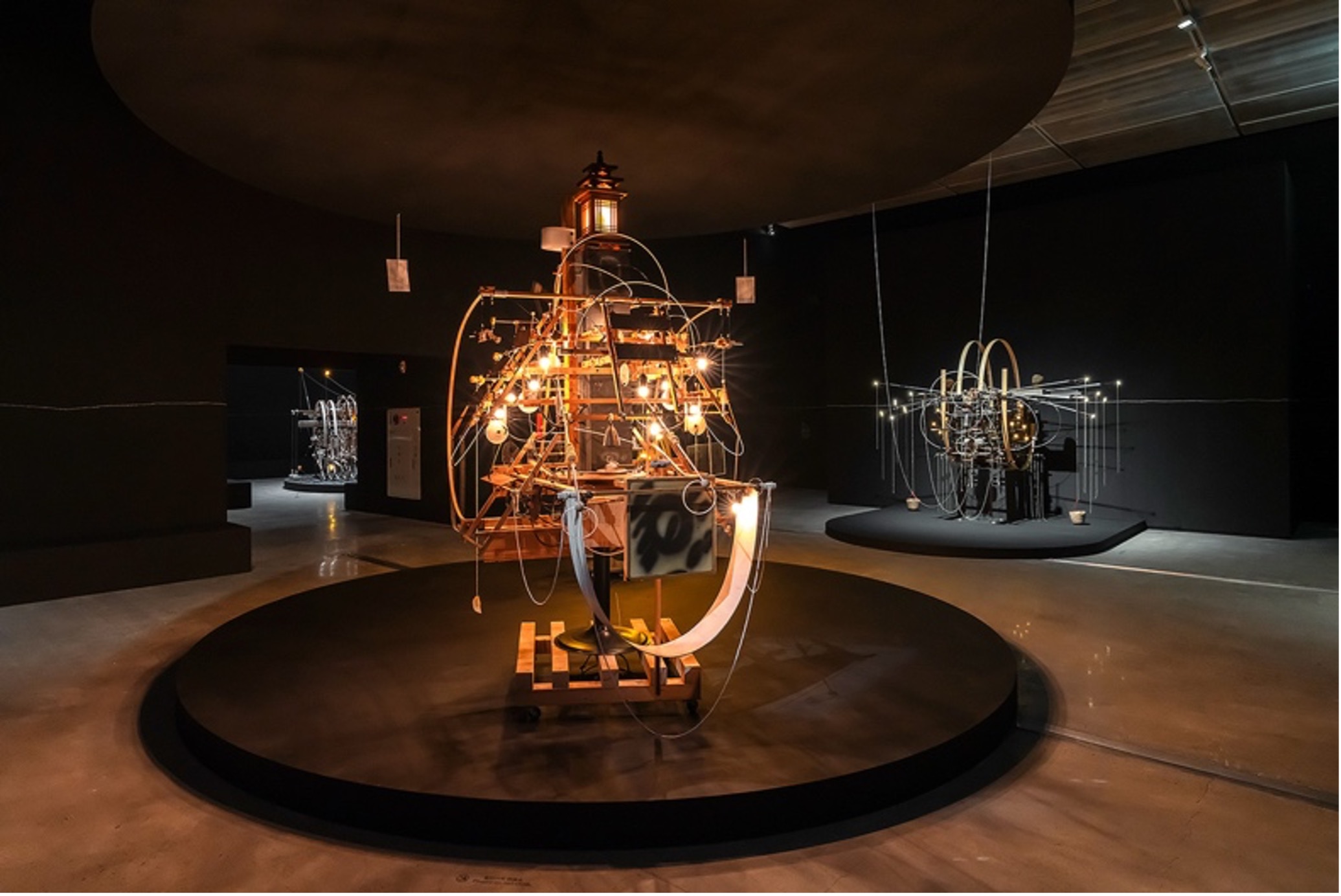

fruit in the small plant sitting between us. I am thinking of tucking this

story away, like one of the small mushrooms that is secretly blooming in my

flowerpot—perhaps inside a lightbulb

socket or behind the wooden parts of Someone I Know, in His

Garden I’ve Never Seen.

2. The Result: An Ear That Remains Forever, Even After the Story

Ends

Sometimes, when someone excitedly shares a story, and I listen

with joy, I wish that these stories would not just disappear into thin air. I

wish that they could hide somewhere, only to resurface and continue drifting on

as endless tales. Sometimes when I hear such a story, I feel that even when it

ends, I want to remain there with that person, still smiling, still clapping,

still moving my shoulders in delight—without needing a story to do so. It is the same with my poetry. I

really wish that someone’s creative work could exist in

such a form, made to float endlessly in the air like an infinite story. Even

after the story has left, I want there to be something remaining, like a giant

ear, staying in place, so that the story never fully fades away.

This happened on a train from Frankfurt to Munich once. My seat

was one of those four-person face-to-face arrangements, and across from me sat

an elderly couple. Tired from my busy schedule, I immediately plugged in my

earphones, turned on some music, and closed my eyes. Even though the sound of

conversation around me grew louder, I ignored it and drifted off to sleep. I

dreamed of chatting and laughing with people, and when I woke up, the woman

sitting next to me smiled and shrugged. Apparently, she believed I had been

laughing at her joke. They were speaking in German, and since I hardly

understand any German, I could not laugh even if I wanted to. Yet in my dream,

I had been part of their group, talking and laughing together. The elderly

couple sitting in front of me continued their conversation with a gentle yet

seasoned rhythm. The woman next to me, constantly amazed, reacted to their

stories with playful remarks. Her laptop work had long been forgotten, as she

was captivated by the old man’s storytelling.

I could not say for certain whether I had been laughing because of her jokes or

not. It felt like I had, and yet it also seemed impossible. Fully awake now, I

quietly observed their conversation; I studied their expressions, their tone,

and their gestures. The conversation I observed had almost nothing to do with

spoken language. I was the last one to leave our four-person seating area. When

the announcement for my stop was made and I stood up, I noticed a large

ear-like object, similar to a cushion, left behind on my seat. I did not know

if the “ear” belonged to me,

but I left it there as I stepped off the train.

As time has passed, I have come to summarize the story I heard

that day like this: upon retiring, the elderly man bought an old house in the

countryside to renovate as part of his plan to move there. However, nothing

about the renovation went as expected. There were conflicts with the neighbors,

with government offices, and even with the spirits that had lived in the house

for generations. After making numerous compromises and adjustments, the house

turned out quite different from the one he had originally planned. The woman

sitting next to me was in awe every time she uncovered a nugget of wisdom

hidden in the old man’s story, and he

responded to her amazement with lighthearted jokes. She laughed heartily, and I

laughed along with them.

3. The Weekend They Do Not Know About2: Urgent Matters

Happen Everywhere

Once, I went to Odaesan Mountain with several colleagues. We chose

to hike the Birobong trail, which takes about four hours, round trip. As we

climbed the mountain slowly, we decided to rest by a stream. Two of my

colleagues sat on a rock, pulling their feet out of their shoes and dipping

them into the cool water. Another colleague unpacked some fruit from their bag

and offered it around to all of us, while yet another colleague wandered off,

talking on the phone at a distance. I sat by the stream with another one of my

colleagues, dipping my hands into the water. The two colleagues with their feet

in the stream were discussing their hiking boots, comparing the new features

and talking about foot fatigue. The fruit that had been taken out lay on a flat

rock, waiting for someone to reach for it. Meanwhile, the colleague who was on

the phone drifted farther away, still engrossed in their conversation. All of a

sudden, the colleague sitting with me and I noticed a baby grasshopper

struggling in the water. In a rush of concern, I grabbed a nearby leaf and

tried to scoop the tiny insect out of the stream. The baby grasshopper appeared

more terrified by the approaching leaf than it had been while struggling in the

stream. My colleague softly exclaimed, “Don’t be scared! We’re

trying to help!” I joined in, also speaking gently, “Climb onto this!” Miraculously, as if it

understood our words, the baby grasshopper crawled onto the leaf and was

finally placed safely on solid ground. However, once on the ground, it simply sat

there, unmoving. Whether it was because its body was soaked or it was trying to

assess the situation, it nonetheless stayed still. A few seconds passed before

the grasshopper lifted its front legs and reached up to touch its antennae. It

seemed that the antennae, which should have been spread apart in a “V” shape, were stuck together because of the

water, making it difficult for the grasshopper to move. It kept using its front

legs to wipe the moisture away, struggling to separate the stuck antennae. The

grasshopper’s movements became more frantic. We held

our breath, watching carefully so as not to disturb it. The baby grasshopper

then became cautious all of a sudden. Very slowly, it began to move its legs

and carefully inserted them between its stuck antennae. Like an elderly woman

carefully threading a needle—putting her magnifying

eyeglasses to her nose, moistening the thread with her saliva, straightening it

with her fingers, and finally threading it through with trembling hands—the baby grasshopper succeeded in restoring its antennae to a

V-shape. With its antennae boldly pointing forward, the grasshopper suddenly

flew off into the distance. My colleague and I cheered simultaneously, and our

fellow hikers, who had been resting nearby, looked at us in surprise, startled,

just like the baby grasshopper had been after being freshly rescued from the

water. After descending the mountain, I could not engage in conversation with

the group even though we had gone to a place we were all looking forward to going.

Still, the others managed to have meaningful discussions and supposedly found a

breakthrough to a project we had been grappling with for quite a long time. For

that colleague and I who had shared the experience with the baby grasshopper,

however, we only talked to one another in hushed voices about the grasshopper

and how it flew away with its V-shaped antennae intact.

4. Socks: Just Like Bangs Grow Up Soon, You and I

I once traveled quite a distance to visit a friend who had been

bedridden for years after surviving a horrible accident, undergoing major

surgery, and coming close to death. At the time, even without a wheelchair or

crutches, my friend was able to walk pretty well beside me. The morning after

we had spent the night together catching up, my friend sat on the floor,

crouching while putting on socks, and said, “It’s such a joy to be able to put on socks

by myself.” The act of bending one’s back to put on socks is something only those with healthy backs

can do, but only those who have been injured, like my friend, can truly

understand this seemingly obvious fact. While waving a pair of socks in my

hand, I joked, “If doing this makes you that happy, do

you want to put on an extra pair?” Ever since then,

whenever I put on socks, I think of that time in my friend’s life when she was struggling with her physical ailment; the slow,

day-by-day healing of a broken body held together by screws; the patience my

friend exhibited while enduring that torturously long period of her life; the

tremendous effort it all required.

5. If You Have Ever Seen Something That Stood Still4:

That Place Becomes the Furthest Edge You Know, Like a Beach or a Cliff

One day, while taking a walk around the neighborhood, I found what

appeared to be a discarded soccer ball in the bushes. The outer layer was

peeling off and the stitches were coming undone. I looked at it for a moment

and walked on. Seasons changed, and then early one morning after a heavy

snowfall, I was taking another walk around the neighborhood, enjoying the act

of leaving my footprints in the fresh snow and the accompanying sound it made

when, in a world covered as if with a white blanket, I saw a round patch of

brown earth exposed. The soccer ball that had been there suddenly came to mind.

Thanks to the round spot of dirt showing through the white snow, I remembered

the old soccer ball. I started wondering where it might have gone. Maybe

someone kicked it, sending it flying high in an arc. Imagining an invisible arc

in the air, I continued thinking about the ball. I imagined it flying off

somewhere and resting quietly with a soft layer of snow covering it on a day

when the snow had melted and then fallen again, only to be kicked once more by

someone. I imagined a yellow patch of grass was concealing the soccer ball and

its torn stitches somewhere. Beside the round patch of dirt, there was a

fist-sized stone covered in a round cap of snow. I picked up the stone. Now,

next to the big round patch of dirt, there was also a small round patch. I

decided to take the stone home—the stone that

had been guarding the side of the soccer ball. It was the stone that had

guarded the soccer ball, the one that had shown me the imaginary arc in the

air. At home, I placed the stone on my desk and started writing some poems. As

I thought about the soccer ball and the arc, I began feeling like I had become

a baseball outfielder. When I opened my notebook, imagination took over and a

bunch of old baseballs, their seams undone, tumbled out in my mind’s eye. All of a sudden, I was standing at the furthest point of a

field I knew, wearing a glove and guarding the edge of the field. Baseballs

kept flying in arcs, and I stretched out my arms, trying to catch them all.

Some balls I missed, but I did not mind. The missed balls, in their own way,

would roll off somewhere and form a round patch of dirt like the soccer ball I

had once seen, wearing the fallen snow like a beret.

Could I ever properly convey such a story to someone? Perhaps

while drinking tea, or during brief moments of small talk in the middle of a

conversation about work. I could, if I wanted to, but I have chosen not to.

These are the kinds of experiences that cannot be conveyed through words—stories that could never be fully understood if told. They are more

fragile and layered than stories that can be shared, and they are felt only

faintly, like someone’s breath. Stories that would not

change anything, even if someone told them out loud.

6. The Invisible Part of Labor

For some time, after getting home from work, I would sit down to

write this piece, little by little, at night. When the sound of cars outside

the open window grew louder, I would stick my head out and take a look. I could

see a line of trucks with their headlights on or a delivery vehicle entering my

apartment complex. In the morning, after opening the front door, items I had

ordered would be waiting in boxes. I would pick up the boxes, bring them

inside, and step back out into the hallway. On one such occasion, I could smell

the faint scent of bleach. Standing on the freshly cleaned floor, I pressed the

elevator button. An announcement came on and mentioned that several trees had

fallen due to the typhoon the night before. At the entrance of the apartment

complex, two workers stood next to one of the fallen trees. I thought to myself

that by the time I returned home, the trees would be standing upright again.

Road maintenance on the highway asphalt usually happened at night, at which

time the cracked and worn road was transformed into a glossy, new road.

Workers, equipped with their tools, must have gone to the damaged highway in

the middle of the night. They likely returned home only at dawn, finally laying

down on their back, which had been bent over throughout the night, to rest.

Every night, I continue to write, little by little. There are more words I have

erased than I have kept. There are more thoughts that have disappeared while

trying to emerge than those that have actually surfaced. Experiences and memories

flicker in and out of existence, never quite materializing into sentences. If

they were made of fluorescent material, my body, while writing in the dark,

would be glowing in the night.

7. Gestures: The Encounter between What Is Seen and What Cannot Be

Seen

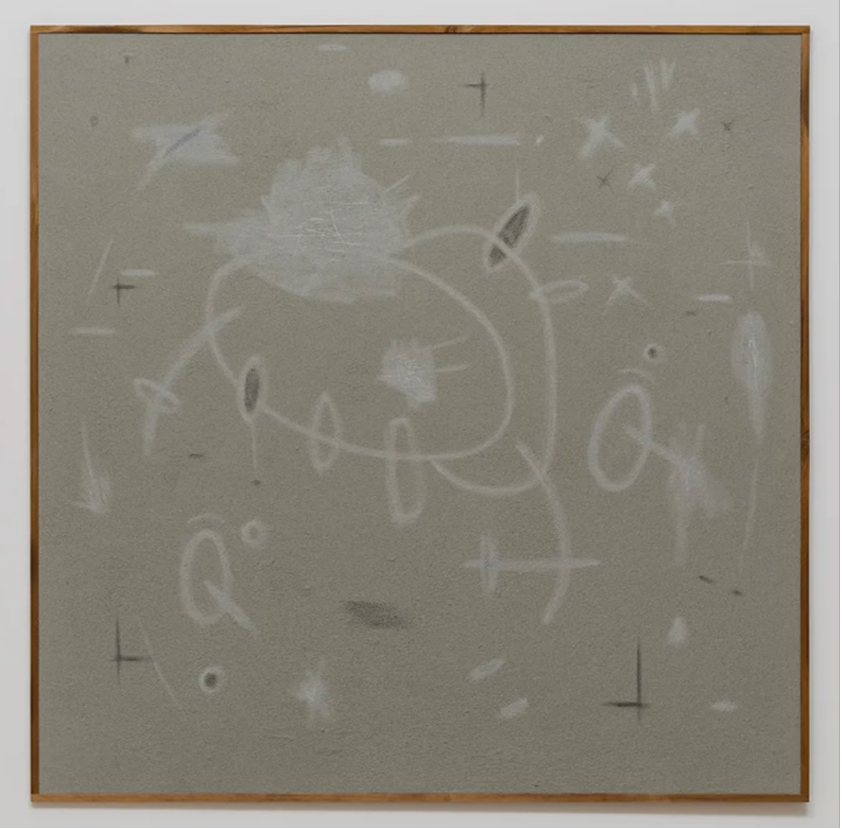

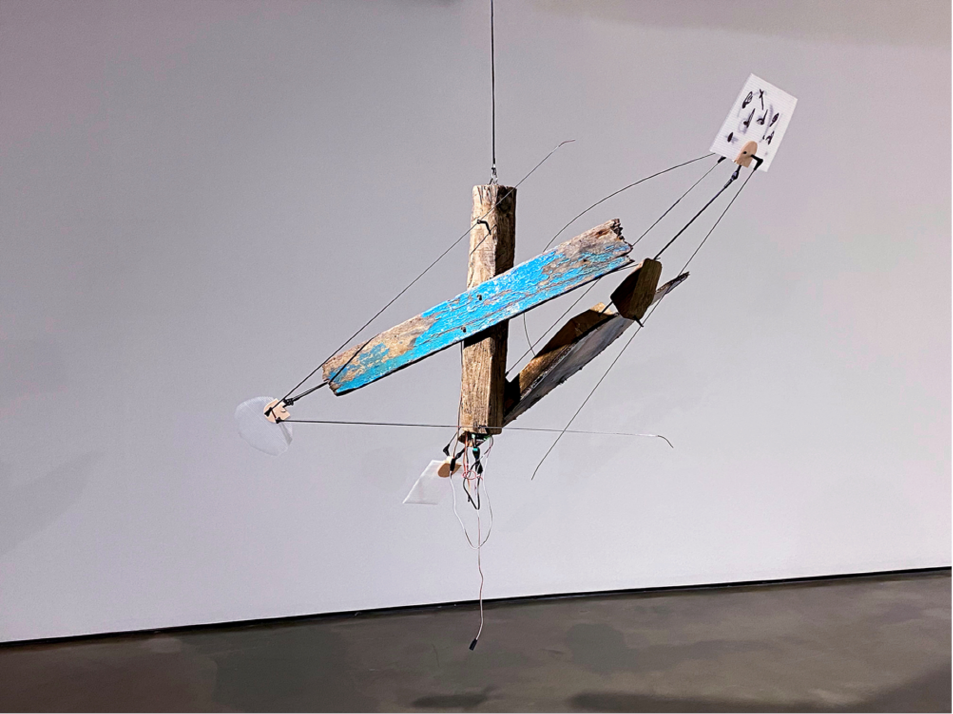

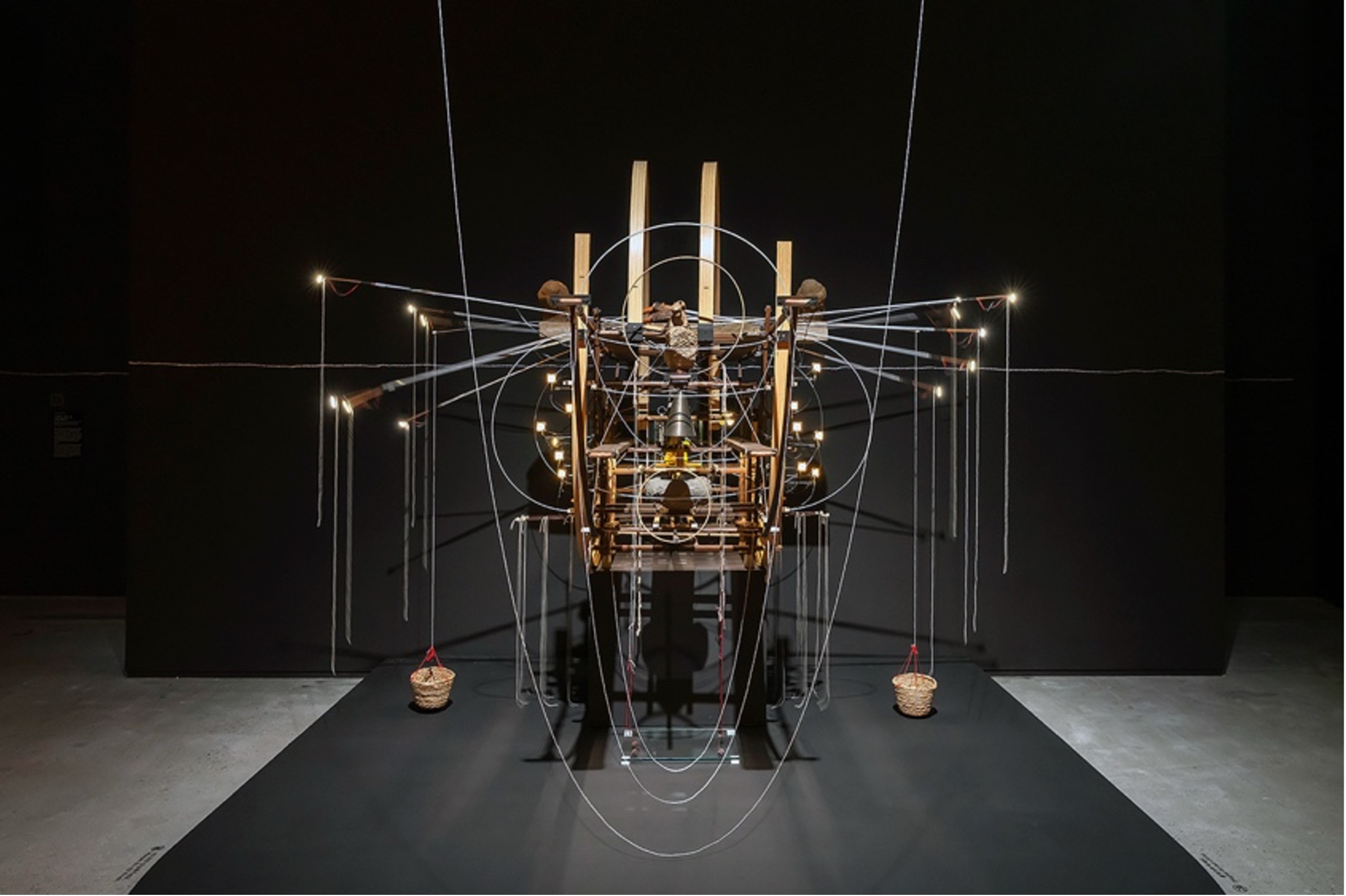

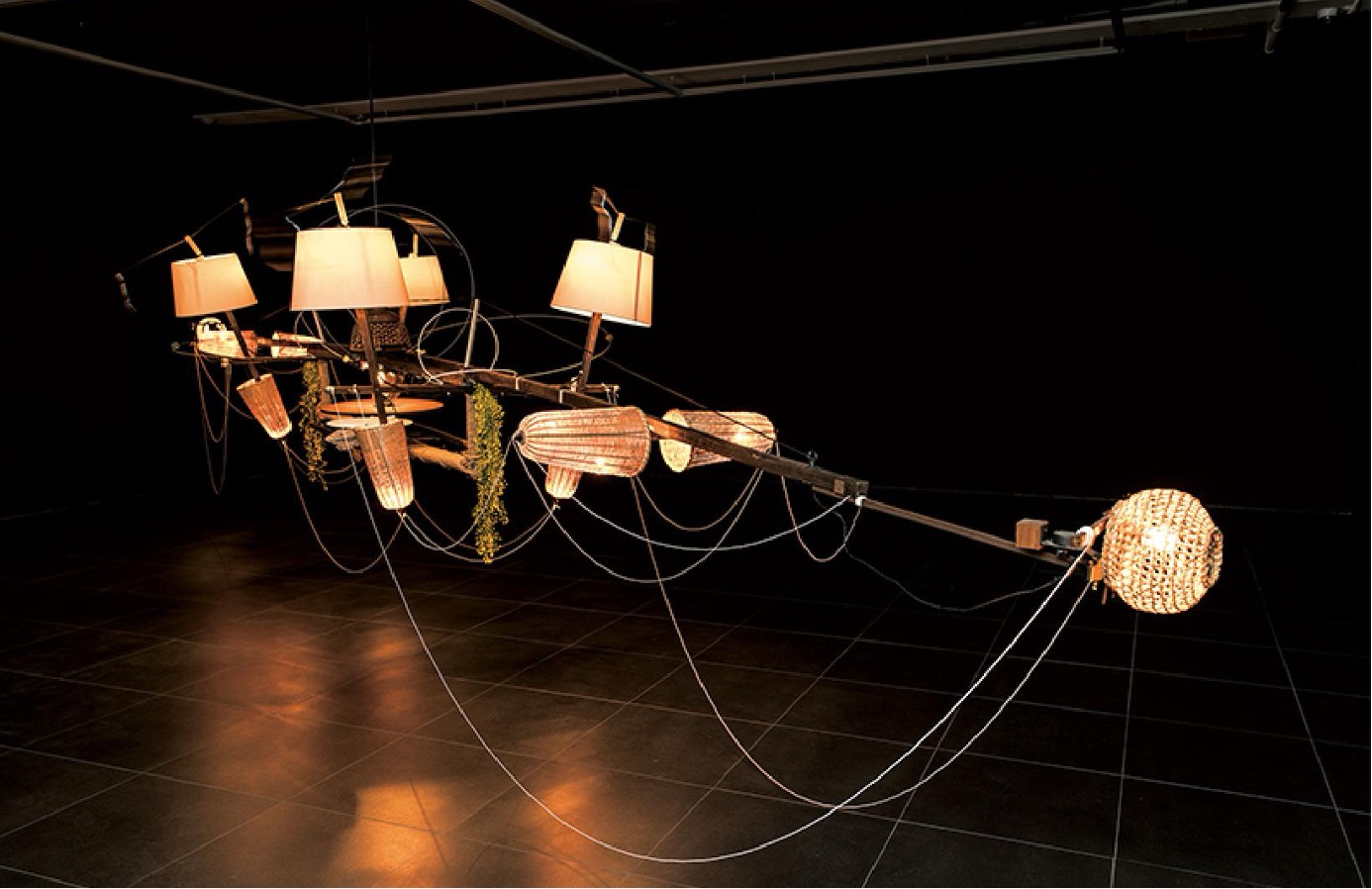

I want to call this a gesture, not just a movement. A single scene

and a single story transform like a tree walking with its roots, its

expressions, movements, and emotions becoming interwoven with the body’s joints. This is how a gesture begins to form. The stagnant air

scatters, moving restlessly as it starts to weave a space different from

before. Any gesture takes on significantly more meaning with the help of

language. It captures and preserves, without omission, the first scene imagined

by the artist, scattering it anew into the aforementioned space—and all without confining it to anything material while also not

relying on any notion of the immaterial. A gesture realizes the encounter of

the material and the immaterial. Landscapes we should have long noticed emerge

in relief from the void. Stories that cannot be clear or concrete, the missing

pieces, meet us in this way.

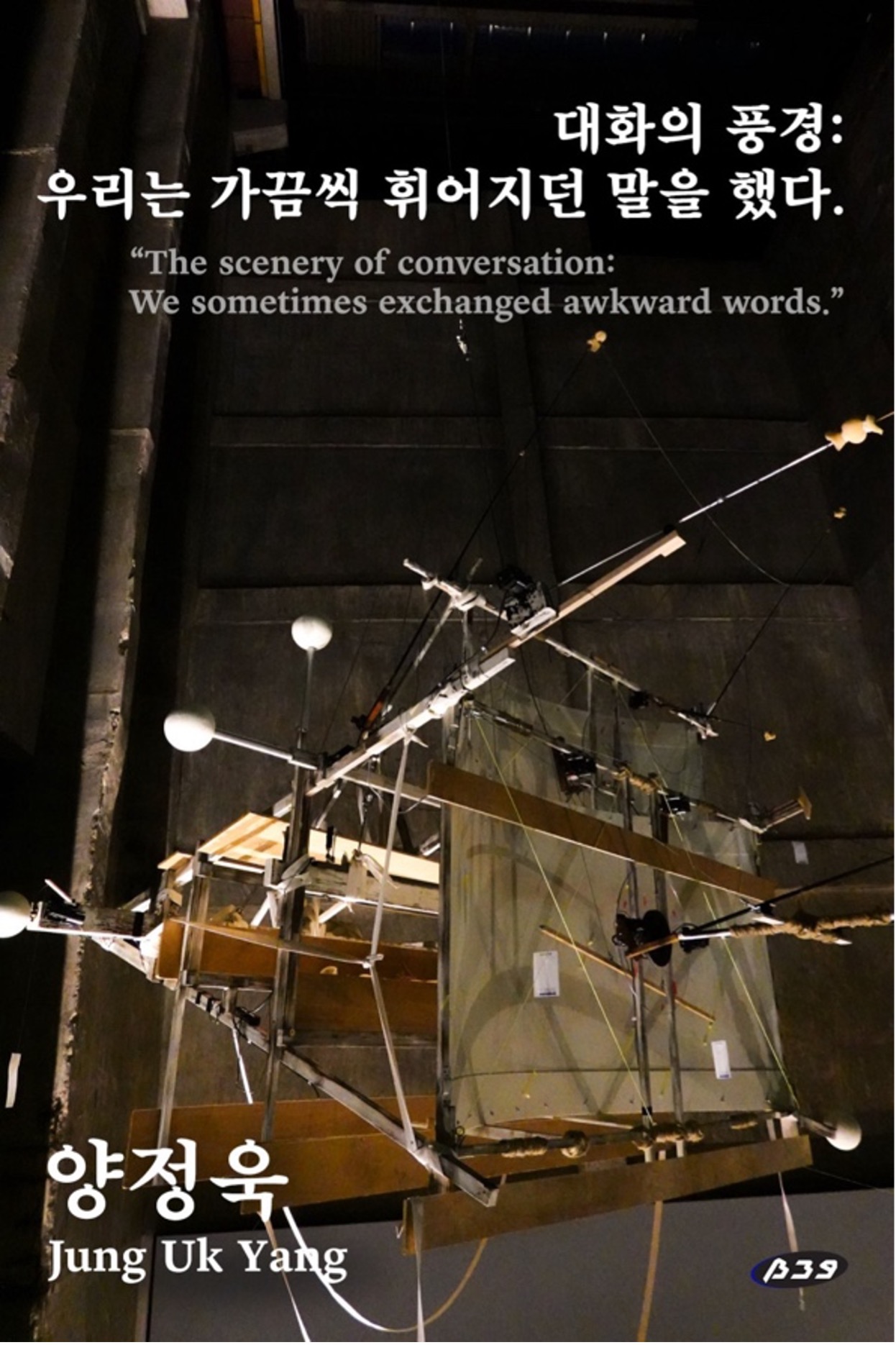

Epilogue. A World that Cannot Be Complete: Beauty Shaped by What

Never Stops and Repeats Eternally

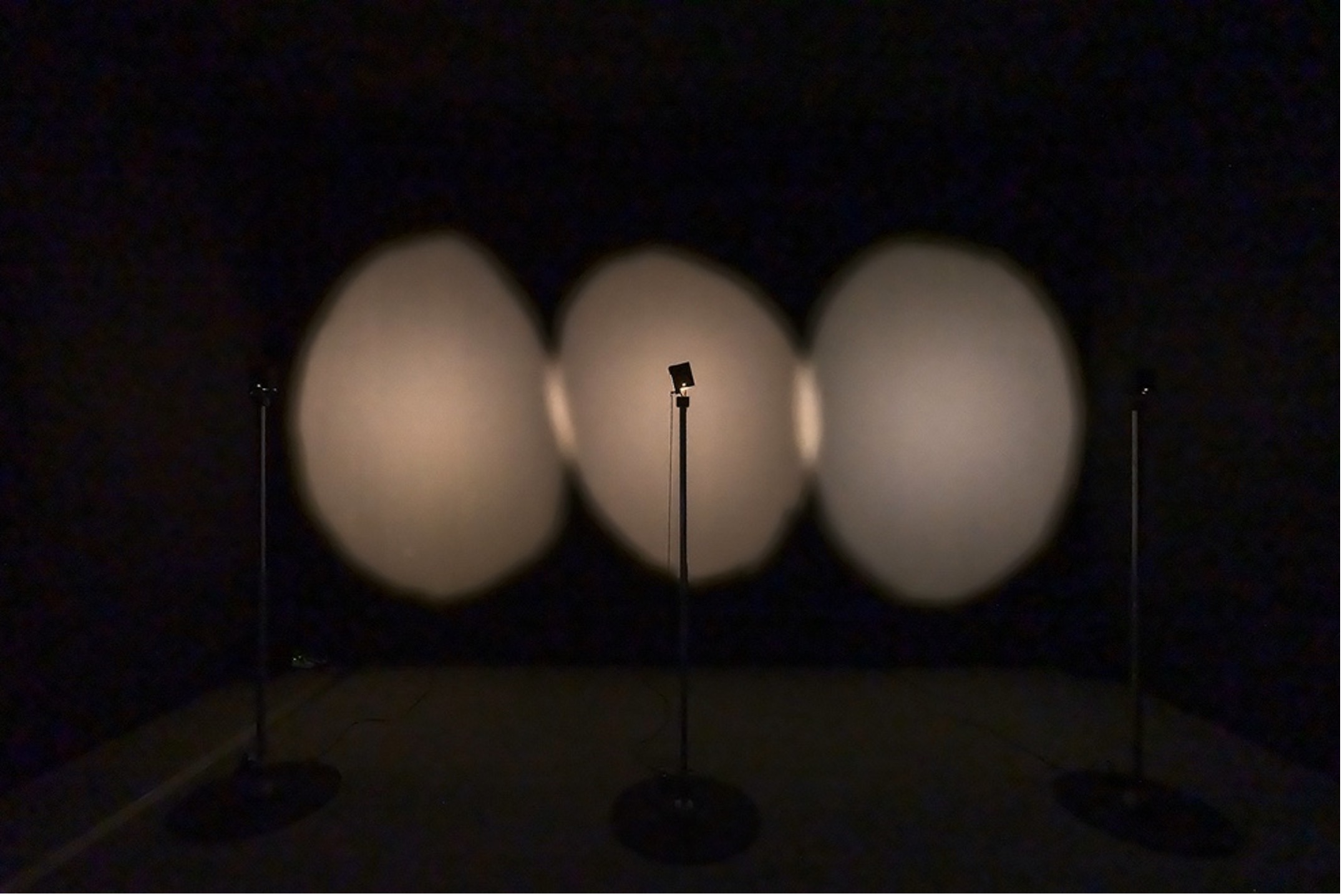

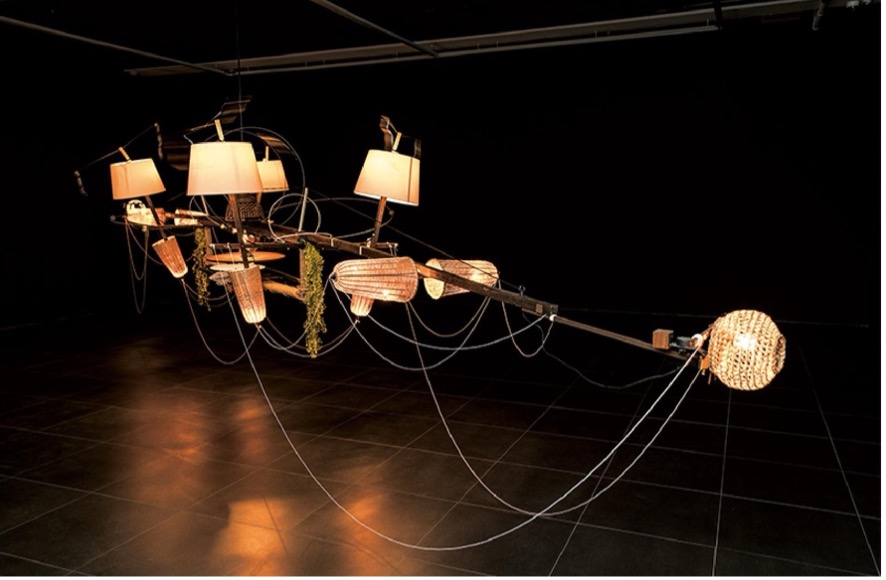

When a piece of art rests under a dim light, stories like the ones

above drift through the softly lit space. They flow gently, with little

strength to grasp anything in their path or simply continue on a slightly descending

slope—and without any desire to dominate anyone’s ear or stir a person’s heart. Fleeting and

weak, they creak as they move along, constantly repeating themselves. Yet there

is a belief in the weight that comes from the eternal repetition of such

fleeting and powerless movements. Though no words are exchanged, a conversation

flows and lingers around us. It seems that when we realize there is a story we

want to tell, this story begins to move, intertwining with our own. These

movements are designed within a non-sophisticated calculation. Movement, while

it is something realized, also functions as a body language that initiates

dialogue. At the same time, it also works as an invitation, suggesting that we

bring forth dialogue. It is a mechanism that responds to the stories we have

long wanted to tell. Like nodding your head, like spreading your lips into a

glorious smile. After we offer stories that we have never spoken before to this

place, we become people who have experienced a conversation we have never had

before.

Scenes we had certainly seen, yet completely forgotten, omitted

from our memory, or deliberately shook our heads at, wishing to pretend we had

never seen them. Stories that, even if told in the language pervading our

everyday lives, would hold no meaning or evoke no emotion. These are not merely

stories but the backgrounds of stories. Like a nut and bolt, the stories and

their backgrounds fit together tightly. The protagonist of a story may become

its background, the observer may become the protagonist, and the listener may

become the main character. In other words, there is a rich tapestry of stories

around us at any given moment. Stories like insects with too many legs, trees

with too many arms, the hidden veins on the back of a leaf hanging from a branch,

or capillaries embedded deep within every corner of our bodies. They were

already stories, but have been waiting a very long time to become stories in

the proper sense. Stories that will continue to live on even after they are

told and the listener has disappeared. Today, I stand before this work as

someone who has received a message that these stories are safe somewhere.