Practicing Extended Gardening

#1. The biomes of Papua New Guinea are relatively isolated from

external predators and climate change, and therefore free from the usual

pressures of survival. The birds of paradise that live in these conditions

devise their own methods of seduction in order to mate. One of these birds, the

bowerbird, is known for bringing together all kinds of shiny objects in

garden-like shelters. Bowerbird males, which are polygamous by nature, do not

concern themselves with childcare. In addition, they build bowers, a type of

shelter traditionally made with sticks, more as a means to attract females than

as a nest, spending much of their time decorating it, except for the three

months when they molt. Male bowerbirds will collect different kinds of

color-specific materials or objects. Anything which has a certain color to it

or is shiny becomes potential nesting material. Among the things they collect

are leftovers, garbage, and plastic jewelry discarded by townspeople or left

behind by visitors. Another skill the bird has is the ability to mimic the

sounds of its environment—they can copy

the sounds of other animals and even machines.

#2. Carl Ferris Miller, who was born in the United States in 1921,

was assigned to Okinawa, Japan as an interpreter officer in April 1945, and

came to Korea as a naval intelligence officer with the Allied forces in 1946.

He took a job at the Bank of Korea in 1953 and was naturalized in 1979, taking

the Korean name Min Byung-gal. Over the course of his lifetime, Miller studied

Korean plants and created an arboretum. He lived much of his life alone,

cultivating his arboretum in Cheollipo, before dying in 2002. He promoted the

environment and plants of Korea through seed exchange programs with overseas

societies, and as early as 1978, he discovered a new plant that was the result

of a natural hybridization of the holly tree and Horned Holly. The plant,

which grows only on Wando Island in Korea, was recognized as a rare species and

named “Wando holly.” It was

later registered as Ilex x Wandoensis C. F. Miller & M. Kim with

an international botanical society. Today, the Cheollipo Arboretum he left

behind opened to the public in stages, starting in 2009.

Today, although their intentions may be different, we may be able

to begin discussing Kang Seung Lee’s work by overlapping the bowerbird’s

behavior and doing three things: explaining the behavior of the male bowerbird

as a decorative act that defies uselessness, even if it is not practical;

making the assumption that it is a courtship gesture, but not solely for the

purpose of mating; and imagining the function of this behavior as a way to

gather or alert other birds by mimicking the sounds of the environment. The

bowers in Papua New Guinea, often referred to as “gardens,” are the result of the collection and arrangement of surrounding

objects, thus becoming part of the landscape. As a result, if we turn our

attention to the life of Min Byung-gal, we can also consider migrating to and

settling down in a foreign country, thereby revealing the invisible to the

outside world and consequently expanding connections with the outside world.

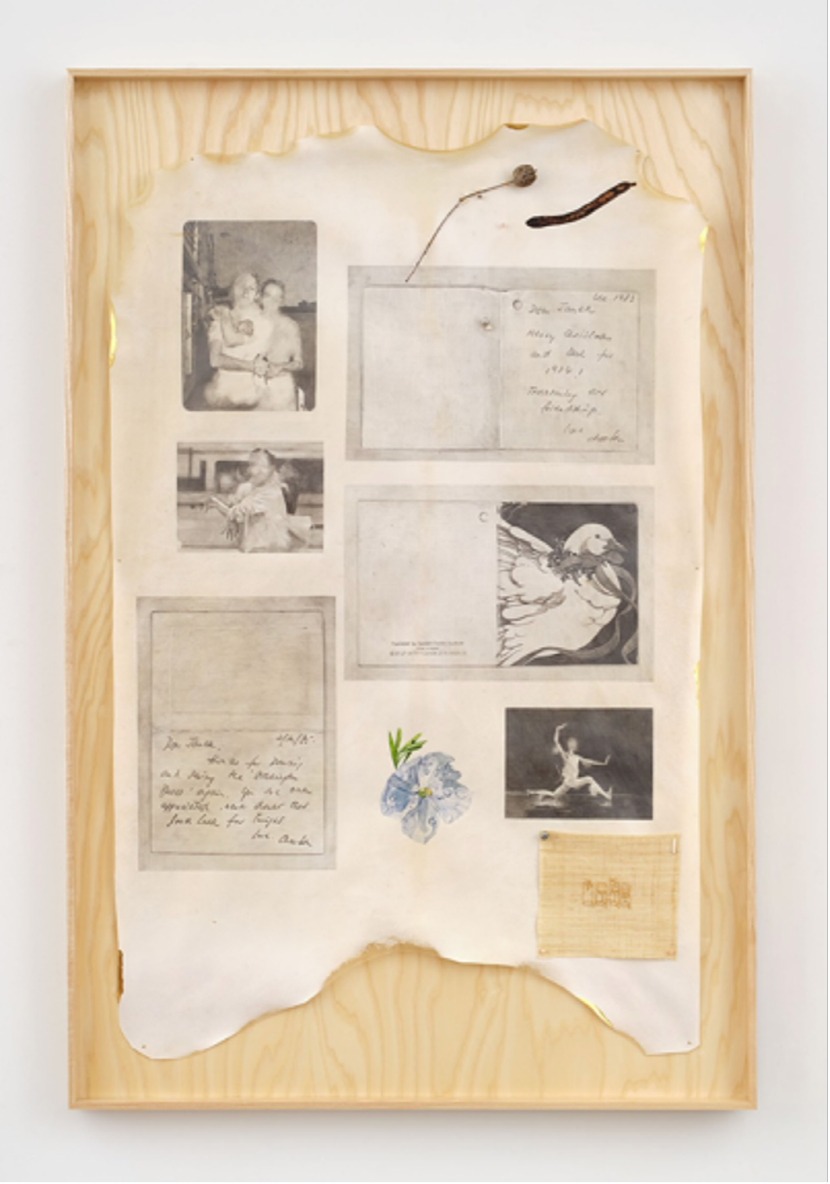

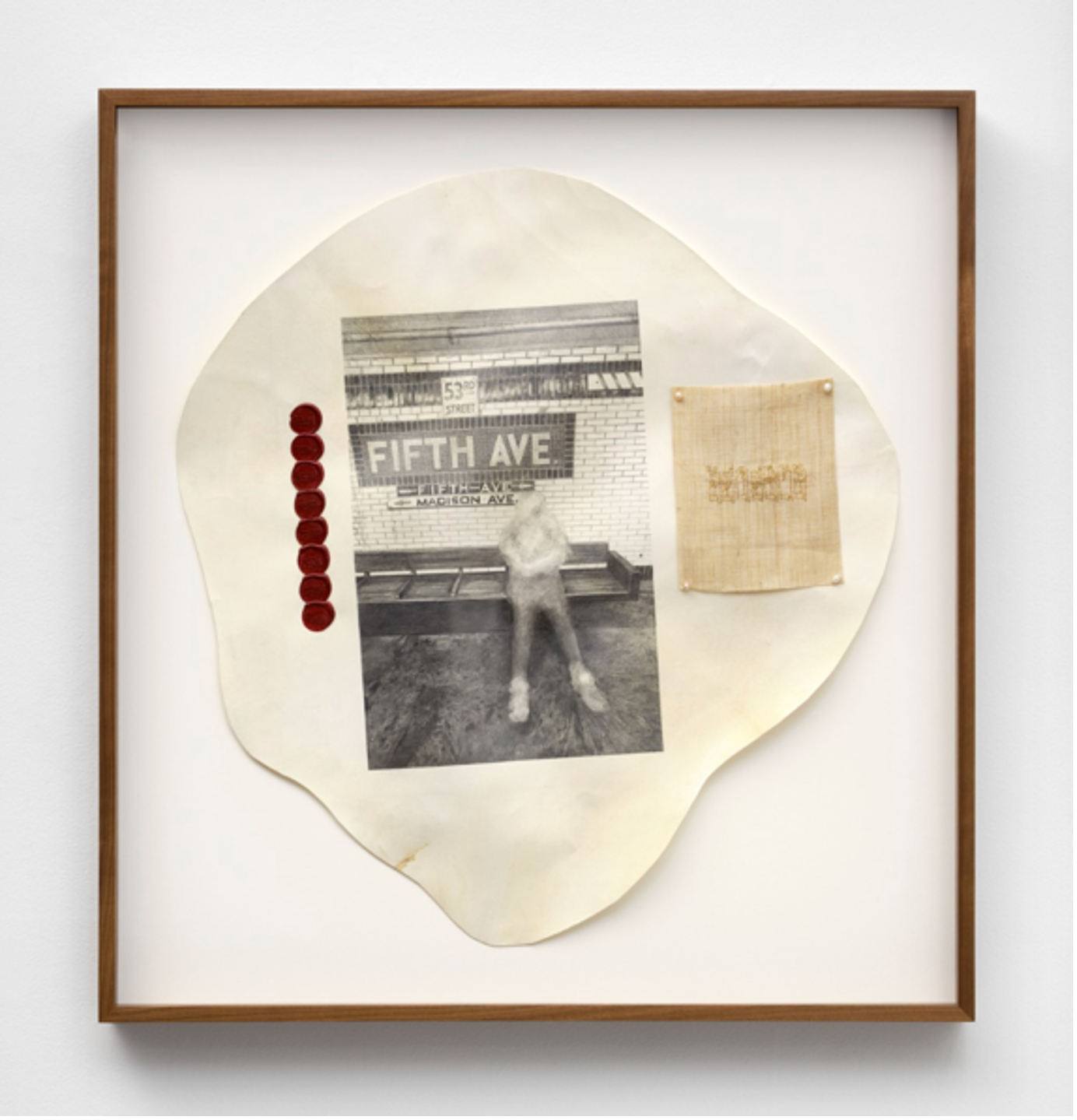

Kang Seung Lee, who is now based in the United States, used the

concept of a “garden” as the theme of his first solo exhibition in Korea in November

2018. Held at ONE AND J Gallery, Garden showed a place and loss—somewhere to remember loss—with the activity

of gardening used to visualize a place for memory and mourning. In other words,

the exhibition showed forms of art though gardening. Taking soil from Tapgol

Park (formerly referred to as Pagoda Park) and Namsan Mountain, as well as Prospect

Cottage in England, and then burying it in a “place

beyond,” the artist stages a burial ritual, while also

carefully utilizing small objects in the process.

Tapgol Park and Namsan Mountain, both located in Seoul, are places

where gay and transgender people used to cruise in the past—and today where they still gather at night—and

have always harbored the shadows of physical contacts and encounters that have

not been officially recorded. Like unnamed sand and weeds, these people have

long been uncounted or rejected, and often portrayed as perverts who occupy

sparsely populated urban spaces, as well as disorderly boundary-crossers who

are vulnerable to crackdowns and public scrutiny. Moreover, the spaces they

occupy are often referred to as slums and remain in need of maintenance and

development.

For Garden, the artist calls on Joon-soo Oh, a longtime

member of the Korean gay men’s human rights

group Chingusai, which has been active in the inner city of Seoul for thirty

years. At the same time, Lee connects to the garden of British queer filmmaker

Derek Jarman. Surrounding a cottage on a barren plot of land in Dungeness,

Kent, southern England, Jarman arranged waste materials from the beach and

planted grasses and flowers native to the coast. With no fences and not a

single tree taller than an adult, the space is still visited by people. Today,

it is an empty area in a public space, a dark site where people meet with a

collection of trash and native plants from the area, and a garden where

anything can find its way in, even during times of constant management because

there is no fence there. Lee’s work of bridging the gap

between Joon-soo Oh and Derek Jarman invites anonymous members of the public to

take part in the garden, those who might otherwise be wandering around a public

space and waiting for someone, and welcomes the uninvited by overlapping

private land touched by an individual on top of a public space. This can also

be approached as an attempt to intervene in the order of the plaza by making

those who have not been publicly recorded in the city’s

history appear in the public space, demanding a share of the citizenry in the

process.

The act of burying things, which takes place in both

locations, intertwines pairs of differences, whether they are places

and times, lives and life circumstances, public and private lives, or

memories of the two men who are bound together by similar sexual

orientation and illness. The two unrelated men, Oh and Jarman, shared a common

life as homosexuals who died of HIV/AIDS in 1998 and 1994, respectively. Even

now, HIV/AIDS, a global epidemic that was often stigmatized as a “gay cancer” in the past, evokes images of

mourning and funerals over the garden here in England. A kind of patchwork that

connects the Korean park which functioned as a nighttime ghetto with the garden

of someone who would have wandered through a park also extends to the actual

stitching of the artwork. The artist embroiders hemp cloth with gold thread,

the objects he embroiders being either shapes designed from excerpts of texts

from his research or images of small objects. On top of the ritualistic

documentation of burying materials collected from one place in the other place,

the method of using handicraft-based labor to add the meaning of mourning to

the artwork is reminiscent of a work for which quilting—a traditional craft still practiced by some North American families—was used to preserve the records and faces of the deceased in fabric

throughout North America and elsewhere during the HIV/AIDS crisis, while

simultaneously recalling the shrouds that cover the body.

The work of interconnecting not only what is remembered but also

how it is remembered shows that the semantics behind gardening as an art form

is extended beyond the simple act of planting flowers and trees. Gardens are

somewhat conservative in that they involve the selection and placement of

plants in a fenced-in space and the creation and maintenance of artificial

landscapes. Crucially, however, gardens cannot help embracing changes, such as

decaying and renewing themselves. Unexpected animals arrive to nest or trample

on the grass. Sometimes seeds fly in from outside the boundaries and weeds

grow. The landscape changes with the weather and the seasons. The act of

gardening utilizes even these changes as elements of creation and appreciation.

Kang Seung Lee shows exquisite skill in expanding the formats of gardening

while making the gardening methodology compatible with a white cube, library,

and museum. At the point where gardener and artist become one and the same—yet diverge as art—Lee manages to reference

Derek Jarman’s gardening practice of collecting useless

materials, though in the place of uselessness, he superimposes the strands of

ethnographic history. He then follows the sparse traces of history, devises a

methodology to reveal them, and intervenes in the linear order of time and

space. In such a way, the artist’s experience of

migrating from Korea to the United States may have served as the background and

motivation for sculpting the unilluminated from the uneven histories of race

and gender to bring them into contact with someone else in a different space

and time to create a synergistic sensibility.

The sensory labor in a garden presents a formal extension of

artistic creation followed by curatorial practice. The artist arranges

reference materials, drawings, and objects in the exhibition space, connecting

and reorganizing their own narratives and subject matters. The connections are

not made at random, but use specific keywords as quilting points. Images of

HIV/AIDS, queerness, missing histories, and shame are private, and they lead to

an attempt to intervene in the previously natural order of the white cube with

faces and names that were only treated as private and have never been

publicized. What is noteworthy is that the act of collecting and arranging

images of fragments and parts of people’s lives confesses not only forgotten memories but also attempts to

remember them as inevitably fragile. The act of searching for traces of

memories leaves the existence of a void, while connecting partial sentences,

images, and fragmentary objects, rather than recreating them with the intention

of fully restoring memories. Although the arrangement is incomplete and fluid,

it holds the possibility that various meanings can be discovered from it. By

collaging drawings and installations, the artist invites viewers to come and

make the effort to connect and rediscover the meaning of each. This leaves

clues—about the bowerbird, the life of Min Byung-gal,

and the Mnemosyne Atlas methodology—that can be

aesthetically appropriated with gardening as a link. Thus, while strongly

connecting the physiology of the bowerbird and the life of Min Byung-gal, both

of which inspire critical interpretations of gardening as an extended field of

art, Kang Seung Lee directly recalls Derek Jarman, who spent his later years

tending to Prospect Cottage in Dungeness. Furthermore, Lee even alludes to the

Mnemosyne Atlas methodology that Avi Warburg used to construct art history,

weaving together disciplines and histories regardless of source or material

much earlier than that. Ultimately, the incompletely recorded materials of

these precarious people lead to a present-day practice that connects at the

artist’s fingertips the vulnerable aspects of memories

that history has overlooked.

Expanding Connections by Starting from Imperfections

The conceptual meaning of a garden—which requires researching the space and its surroundings, and

constantly managing and refining all of it—is both a

motivation and a reason for summoning the places of those who have always been

consumed with an image of shame only. The attempt to connect gardening as a

methodology of artistic work opens up the possibility of expanding the

interpretation of gardening as well as its skill in the curation of art spaces.

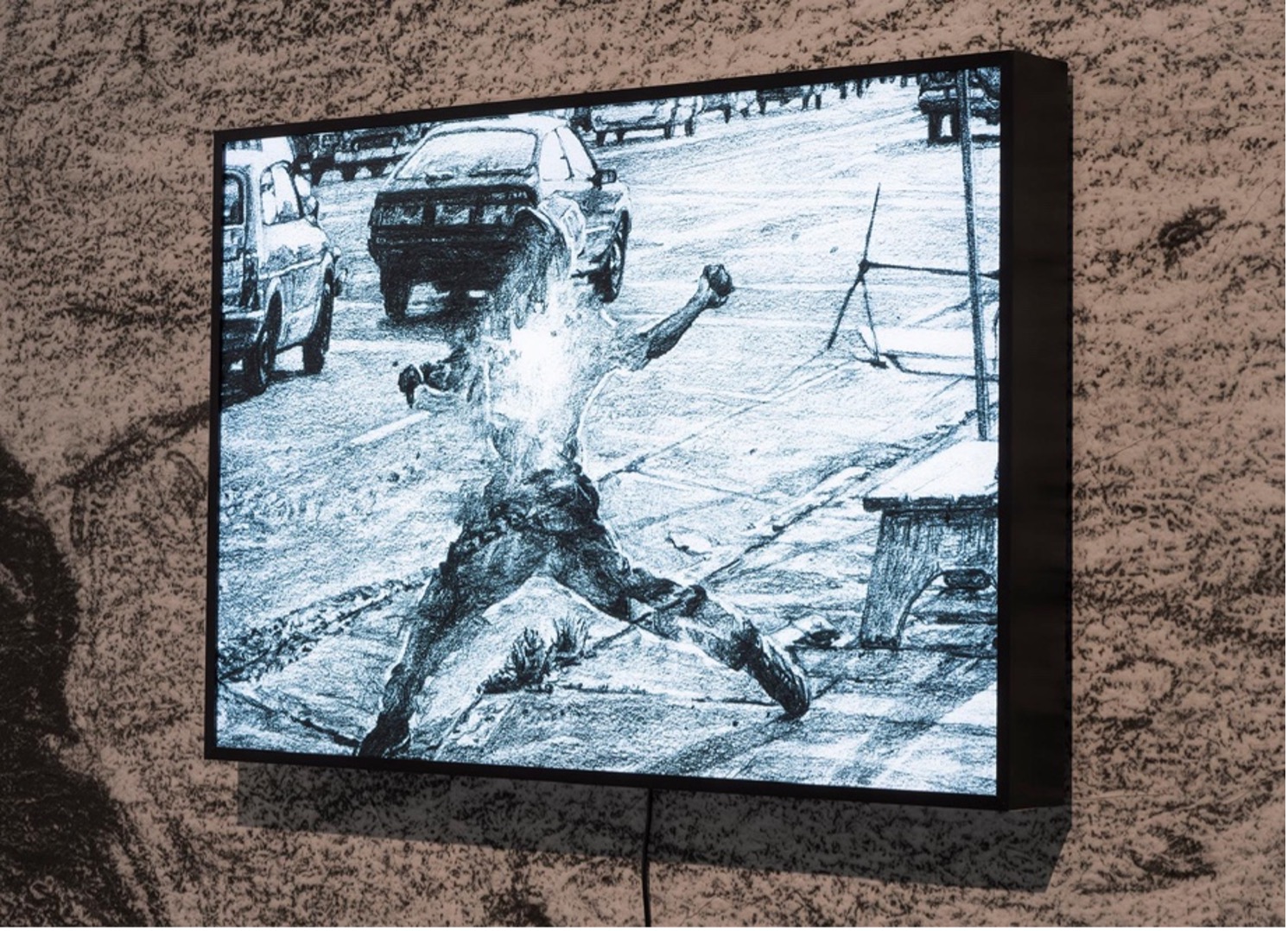

In the exhibition QueerArch, held at the gallery Hapjungjigu

in October 2019, the attempt to grope for disturbing faces in the media and

unremembered communities became more serious. Here, Lee was not only an artist

but also a curator and exhibition director. As he organized an exhibition that

connected “queer” with “history” as

the main keywords, he called on artists and colleagues from all walks of life.

(To be more precise, in Lee’s own mind, these people

became immediate colleagues of his by being called upon to work together.) If

the faces in the drawings are objects of mourning and memory, fellow artists

and activists remember and honor them based on the drawings and give them

contemporary meaning.

It was at QueerArch that Lee’s curatorial practice really came into its own. In the 2019

exhibition at Hapjeongjigu, he invited artists to participate in the act of

collecting and arranging, and encouraged them to create artworks based on a

public archive named the Korea Queer Archive. Fashion designer Kim Se Hyung

(a.k.a. AJO), archivist and researcher Ruin, artist and stage performer Moon

Sang Hoon, drag performer Azangman, visual designer Kyungmin Lee, and sculptor

Haneyl Choi were invited as Lee’s colleagues to

participate in the exhibition and present queer histories, as well as to

present queer collecting and archiving practices related to queer histories.

Although it falls under the category of art curation, the attempt to gather

fellow queer artists, give them a mission based on Korean queer history, and

exhibit their proposed works also had the effect of creating a temporary sense

of community. The participants researched the reference materials and recreated

formats that reflected their own context. This, of course, was based on thirty

years of LGBTQ+ activism, which had continued to demand a place in the public

realm for LGBTQ+ people who had historically been forced to live in

marginalized environments. It is worth remembering that while the previous

Garden exhibition was made possible with the help of Chingusai, a Korean gay

men’s human rights group that Joon-soo Oh was an active

part of, QueerArch was able to take their materials out into the open and

display them or utilize them as material for the exhibition through a

collaboration with the Korea Queer Archive. Conversely, collecting materials by

tracking a community, and coming up with devices to preserve them, can actually

contribute to the community. Therefore, the inclusion of collaborating artists

in the exhibition credits is a reminder that Lee’s

exhibition cannot remain a personal achievement and narrative. The work of

organizing the exhibition by making connections inside and outside of art

allows us to perceive a queer community that has once again responded to a

crisis, that is, the contour of a queer community in which members sought each

other out in order not to be isolated in a crisis, and that sought safety and a

new tomorrow through a crisis.

Furthermore, Briefly Gorgeous, an exhibition held at Gallery

Hyundai in 2021, shows how archival practices should respond to a situation

where the past cannot be fully summoned and the present is in crisis. In the

shadow of social disasters, including the outbreak of epidemics, everyday

social inequality and discrimination are magnified. Vulnerable places and

groups are targeted and attacked, and those who are not counted as citizens are

not included in those to be protected through the prevention of disasters. The

garden work of uprooting diseased branches and species is carried out in the

world as discipline, confinement, targeting, and stigmatization in a

life-or-death environment. In the midst of any pandemic, confused authorities

and the media take pointless ad hoc measures, while being quick to target

specific groups, accusing them of spreading a contagion through their senseless

disregard for taking any precautionary steps. Yet the people they target are

often the most vulnerable and in desperate need of community. In 2020,

migrants, delivery workers, and gay men in clubs were vilified with spreading

COVID-19. Early the following year, a series of transgender suicides made news

in Korea.

The disaster of a disease-ridden epidemic is nothing new. For the

2021 exhibition, Lee thought back to Asian artists among the artists who died

or survived the HIV/AIDS crisis, including photographer Tseng Kwong Chi, who

was born in Hong Kong and died in New York in 1990, and Goh Choo San, a

Singaporean choreographer and ballet dancer who brought fame to the Washington

Ballet in the 1980s. In addition, he juxtaposed drawings of the late Kim

Ki-hong, a South Korean transgender activist and music teacher, and the late

Sergeant Byun Hee-soo, who was forcibly discharged from the Korean Army after

undergoing gender reassignment surgery, both of whom died in early 2021. His

process of shedding new light on them is often described as an attempt to

challenge not only heteronormativity but also white-oriented queer histories.

Recently, he seeks to sculpt forms of connection by extending his artistic

attempt to ever-present contemporary crises. Photographs and video footage,

ceramics and canvas paintings, notes and doodles, flowers and grasses, and maps

all showed a careful arrangement of fragmentary images, texts, and objects,

rather than being something definitive or monumental. The reconstructions,

which reference patchworks and mosaics, integrate past and present times—those who stood or fell in different regions and contexts, and

contemporary perceptions and sensory elements—while

maintaining a particular sense of place. Together with El Salvadoran writer

Beatriz Cortez, the artist asked his colleagues what a “queer future” would look like, and then

asked them to complete their sentences in the future tense: “When the future comes, I will…” Those

sentences would have been a collective mantra that gathered the longings of

individuals dreaming of an ideal future instead of the status quo based on the

faded records of those who had not been counted in the trajectory of history

and on the desire of the person seeking to find those hard-to-find records.

In the basement of the exhibition hall, the logo of Itaewon’s King Club, a nightclub that was targeted during the COVID-19

spread in Korea, set up as an assembled puzzle-like object, with music

playlists from fellow artists played in a club-lit space. While the lights, a

mirror ball, and objects unfolded to the music in the basement, archival

materials were placed on the first floor, while the second-floor walls were

covered with hand-drawn faces. The exhibition was organized so that visitors

could explore the underground club, the archive on the first floor, and the

specific faces and traces of one’s life on the second

floor. This came about as a result of observing queer spaces in Korea and

reorganizing the flow of their functions in the building structure of the

museum. An example of memories and a sense of community being embodied in a

specific space seemed to have been organized in a more community-oriented form

than in the special exhibition Looking for Another Family (2020), which was

held at the MMCA Seoul a year earlier than Briefly Gorgeous. For the 2020

special exhibition, Kang Seung Lee created a lounge-like reading space. The

books selected by literary critic Hyejin Oh, while wary of being treated (as

described by Oh at the time) as “a synecdoche of a

certain purposive intellectual history or a fetishized object of queer

heterotopia” or “an obsession

with the queer,” constituted an arbitrary and fluid

network, revealing that this exhibition space also has the meaning of a

temporary occupation. However, unlike Lee’s intention,

the open space became the hub of the exhibition, giving the impression of

connecting the works by other artists around it. The viewers wandered around,

thumbing through materials and looking at videos and drawings. The arranged

shelves and furniture functioned as partly closed partitions and, at the same

time, fences that blurred the boundaries between the two—and yet also connecting the two. In and around them, Lee displayed a

collection of queer-specific content and images. The nature of the site, where

a community’s private history and archives are knotted

together in a public space, was reminiscent of the ghettoized nature of a

certain group (such as queer people, for example), but also of the design of

urban spaces that connect in all directions.

However, the work at the special exhibition may have left a

different impression on visitors than Lee’s Covers (QueerArch) (2019/2020), in which he collected

the covers of publications covering queer-related papers, magazines, and books,

made them into scrapbooks and wallpaper, and pasted them all over the

exhibition space. The work, which seemed to encompass everything at once, gave

the impression of overwhelming the space by spreading

vertically and horizontally the recorded materials and research of

those who have somehow created their own language and grammar despite being

placed in a peripheral position within the existing market and system. Indeed,

it created the effect of a quantitative spectacle, while also relying on an

archive that spans the keyword and framework of “queer.” Although this is not like the direction of Oh’s notes from the earlier book selection, we need to keep in mind

that this is another limitation of the work: it simply cannot be

all-encompassing. Lee’s work, which is incomplete and

promises to be endlessly continued, focuses on admitting that nothing can be

fully collected and given meaning, and not on uphold an exclusive identity by

giving meaning to everything. Thus, a methodology that is close to a

collectomania emerges as one of selection and editing when it comes to

exhibition curatorial practices, including archival spaces. In this case, the

markers of whose point of view or criteria have been applied complement each

other by inserting collective opinions into empty spaces and by embracing ways

to secure and organize a space where we can examine those opinions one by one.

The imperfection of memories and conservation are the inevitable limitations of

any community and the basis of all connection.

Disturbing Memories and a Tangled Future

Lee overlaps the records of public and private lives, featuring

past figures and surviving subjects—as well as the memories of life and death—all

in one exhibition space. The artist juxtaposes subject matters with different “grammar” (i.e., ways of interpreting things

or people) and value, while also reinterpreting discovered reference materials

and proposing new “grammar”

rules. This artistic practice follows the unfair context in which the lives of

others are obscured, and reveals those people who have been filtered through

this unfairness.

However, the virtue of being revealed also becomes a concern for

exposure. This is because the lives and faces introduced in art spaces can be

easily bleached as objects of representation and aesthetic representation. We

may suspect one thing here: The traces of people’s lives that the artist has drawn from—the

representations that failed to be remembered earlier—may

serve to remember and introduce the times and faces he tried to draw from while

only giving them meaning as the lives of the Others. Or, on the contrary,

does the work of targeting the Others not easily leave behind an attitude of

respect and consideration? In other words, the attitude of respect for

vulnerable records and objects secures the virtue of giving public meaning to

the memories, people, and materials that the artist has unearthed by presenting

them in the exhibition hall. On the other hand, there is also a concern that he

may inadvertently capture someone as the Other. This concern acts as a

reason for doing nothing more than intervening in the targeted beings and

renewing their time in the form of art. In other words, there is an essential

dilemma in dealing with the Other: the revealer and the revealed are not placed

in equal positions. When other people’s bodies, their

sensory representations and records, and their lives and histories are placed

in the forgotten and obscured realm, they are once again framed as

the Other that should be discovered and named.

One-sided referencing & representation, and the attitude of respect and

consideration seem to be contradictory, but they are common in that they

separate the subject from the Other without doubt. Therefore, the position of

the Other as an archival object once again summons the status of the subject

who collects, edits, reconstructs, and uploads it to the art space. Although

the two kinds of attitudes may reflect on themselves, do they not inevitably

uphold the position of the artist as a reflective subject who reveals and

rearranges subject matters that remain hidden? What kind of destructive force

can this subject secure? In addition, how can the lives and bodies that appear

at the invitation of the artist go beyond restoring honor from the past shame

and continue with their disturbing values and desires?

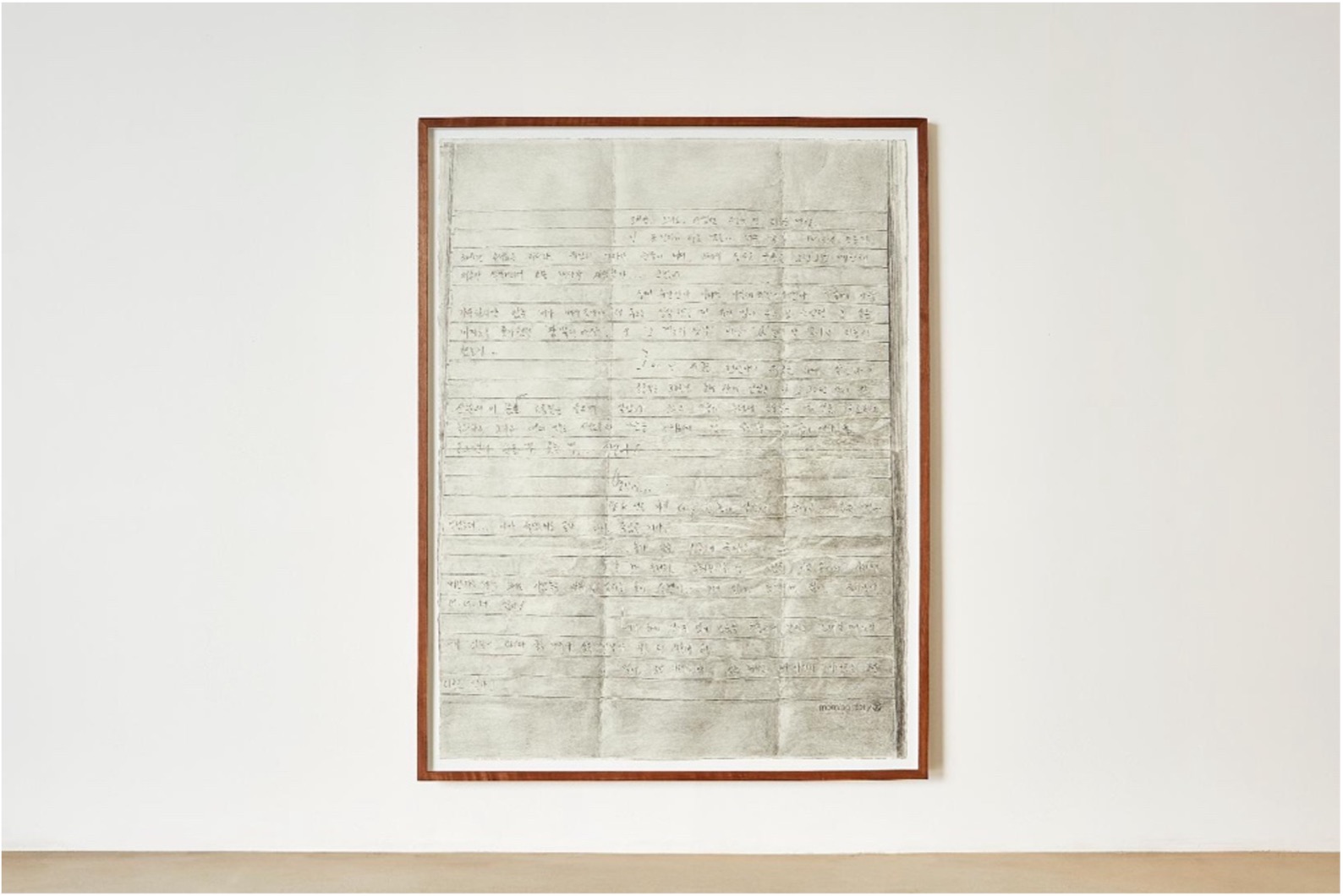

Before answering those questions directly, let us shift or

attention to the drawings for a moment and take a slight detour. The pencil

(graphite) drawings, which delicately match the light and shade, as well as the

tone, encompass a variety of subject matters, not only figures but also

newspaper articles, local vegetation, and pebbles. In short, he does not miss

any letter of any word, any crinkle in the paper, or any holes in the stones he

comes upon. However, rather than describing the subject matters with lines of

conviction, his pencil wanders across the canvas like a smudge, making and

crushing shapes, with the trajectory of this crushing creating the shapes.

Sometimes figures are drawn partly erased. The marks of erasure and crushing

remain like smoke or stains, appearing as the evaporation of a figure’s place. This is both a meticulous depiction of the time he failed

to capture and a gesture of refusing to be captured in the first place by

leaving the faces of others as ghosts. He thoroughly draws the records in his

hands, but leaves them blank or burns the corners to create soot, as if to

admit that he cannot fully capture them. At this point, it would be easy to

categorize his work as a typical representation of the inability to capture the

faces of others.

Lee’s drawings also

include renditions inspired from the photo series East Meets

West (1979-1989) by the aforementioned photographer, Tseng Kwong Chi. The

way Tseng practiced his art during his lifetime leaves clues as to how and

approach Lee’s drawings differently. Wearing sunglasses

and dressed in a Mao suit, Tseng Kwong Chi pressed a button in his hand to take

pictures in front of iconic and typical American and European landscapes. The

resulting pictures are said to have performed a stereotype perceived by the

eyes of others looking at Asian people. The recorded materials frame one’s isolation as being part of the landscape, and show the tension and

competition of the gazes that refuse to be captured by hiding the artist’s own eyes. In Kang Seung Lee’s case, he

draws the photographs someone left behind, erasing the person’s face rather than trying to recreate it, and imagining the spot

where it was erased. The artist’s painstakingly precise

depiction suggests that the motivation for his drawings is the impulse to

thoroughly express a longing for the memories that cannot be fully recalled and

restored. Additionally, the method of erasing and leaving empty spaces in

drawings makes a critical reference—from a contemporary

perspective—to Tseng’s tireless

attempts to devise a form of visualizing himself while at the same time

distancing himself from the lens through which people of color were viewed. It

would not be unreasonable to approach this as an exquisite form of

memorializing an artist who passed away from HIV/AIDS. For him, Lee took into

account the concern that the perspective Tseng took during his lifetime might

be captured as an archetype of a possible choice by an East Asian artist who

lived in the developed world.

Conversely, how should we understand Lee’s conflicting modes of representation that bring to the forefront

the faces of Joon-soo Oh, Kim Ki-hong, Byun Hee-soo, and other unnamed queer

figures from the past? The statuses of those who can claim citizenship by

revealing themselves and those who erase themselves from the race, nationality,

and gender stereotypes that imprison them are not that far apart. However, it

is important to note that the choice to reveal or not reveal depends on the

local political situation, who is the Other that is represented as an object of

art, what lifelong attitude the person expressed during their lifetime, and the

social context in which it was formed. There are people who have resisted the

power of representation that categorized them as subordinate subjects and

repeatedly reproduced stereotypes. Beyond them, we also need to remember the

names and faces that those people—those same people who

had not been recognized behind the over-represented—desperately

tried to leave behind.

We need to note that the method of representation, that is, one

which is devised by looking closely at the environment of those who lived in

those days, continuously reconstructs relationships by looking at the context

of the time and leaving room for reinterpretation from a contemporary

perspective, rather than only looking at others who have lived or died earlier

as the objects. Thus, Lee not only invites fellow artists, writers, activists,

and others to engage in critical archival practices as he seeks to interconnect

contemporaries but also to include artists of past generations as contemporary

colleagues, invoking the methodologies of art practiced during their lifetimes

to renew and give new meaning to these methodologies in the present.

Lee’s collage-like

arrangements and drawing methodology have recently been presented in the form

of gestures, on the stage and on the screen. Clad in the easily forgotten

rhythms of the body, the artist takes up the motions of the past and creates

contemporary gestures. In fact, he designed a font derived from the American

Sign Language used by Chinese-American artist Martin Wong, who died of AIDS, to

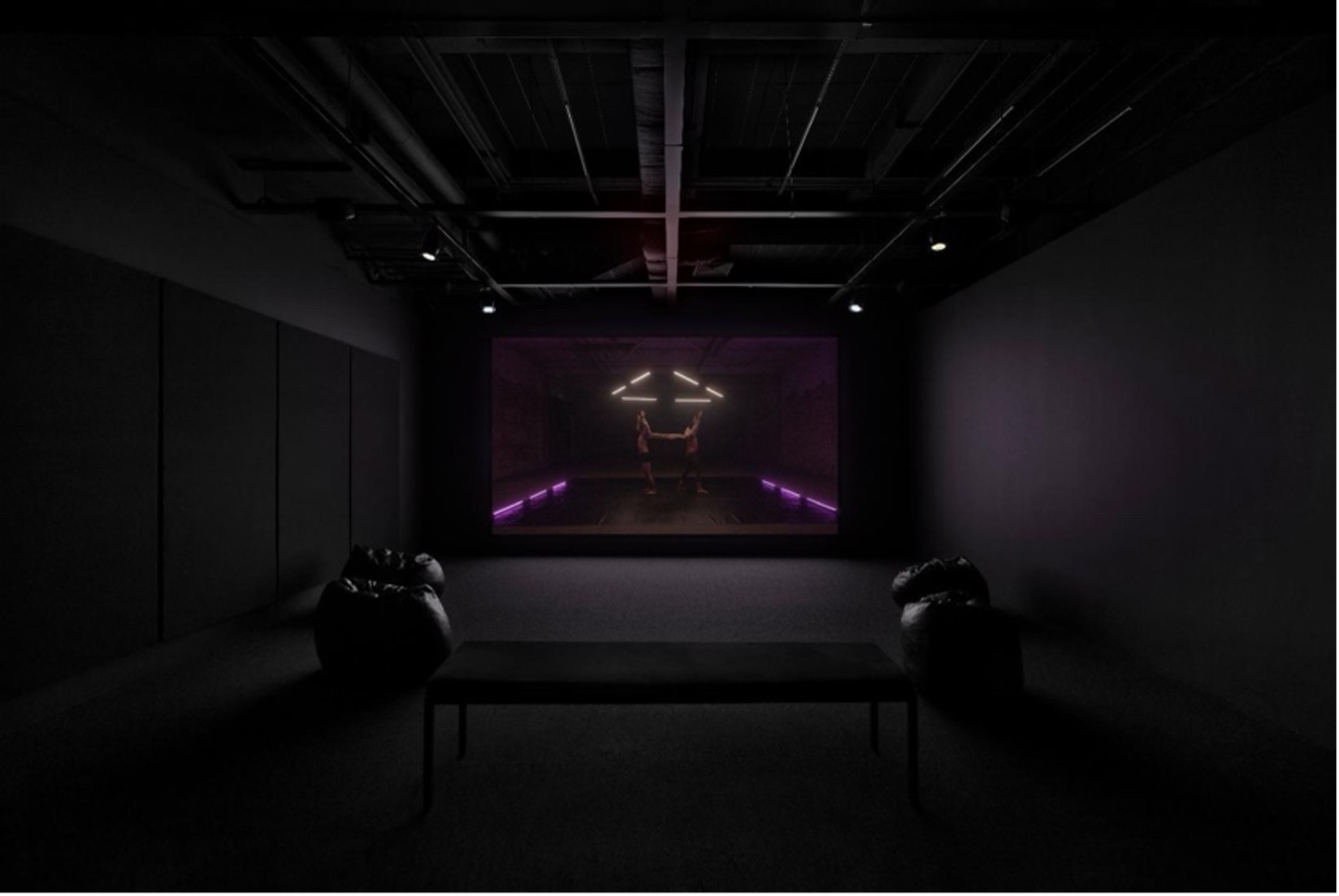

apply it to sentences in Lee’s own works. In The

Heart of A Hand, Filipino transgender/nonbinary choreographer Joshua Serafin

deconstructs Goh Choo San’s 1981 dance Configurations

to set it to the music of Seoul-based transgender musician KIRARA. The artist’s call to remember and adopt the gestures of queer artists—but also to express one’s own disturbing

gestures and gazes right now—may be a prelude to a more

radical gesture: While adopting the past as an artist-subject, he cannot simply

make divisions between the past and present. Lazarus, which premiered at

the Korea Artist Prize exhibition, referenced and networked simultaneously,

like the release of a held breath. Based on Goh Choo San’s original ballet Unknown Territory and recreated by

choreographer Daeun Jung, two male dancers express their interaction with each

other by donning and doffing costumes with two dress shirts sewn together up

and down, in reference to Lazarus (1993), the last known work of

Brazilian conceptual artist José Leonilson. By incorporating text from queer

Chicano artist Samuel Rodriguez’s 1998 experimental

video Your Denim Shirt and transcribing it into a font using the

American Sign Language invented by Martin Wong for his paintings, and by

collaborating with L.A.-based filmmaker Nathan Mercury Kim and using KIRARA’s music, the creation process is in the form of condensing the

separation between past and present, as well as the collaboration of

contemporary artists, onto a single stage. This allows for the prospect that

his future work may attempt to cross-reference and even appropriate between

collaborators and references. It invites us to examine the marks of faces and

bodies that appear erased in Lee’s drawings, and the

outlines of faces and bodies that reappear from them.

If the above stages imply complex references and processes, asking

the viewer to make an intellectual effort to appreciate them, his objets d’art reveal the process of more intuitively disparate contexts

meeting in a material way, meaning viewers can see this aspect concentrated

throughout his ceramic works. He collects soil from different places, kneads

it, fires it in a kiln, and makes pots, which he then fills with other soil and

transplants plants grown by a person he remembers. While the objects intersect

different points of reference, each material functions as its own indicator of

memory, and the viewers can savor and connect with the memories by alternating

between the captions and the ceramic objects. The methodology of ceramics is a

mashup of subject matters and materials beyond collection and collage, opening

up the venue for networking through a stage where gestures and rhythms are

generated again, not only referencing and paying homage to the past but also

weaving in collaboration with contemporary living artists.

Conclusion

The journey of expanding the collaborative relationships with a

work’s references and renewing them by crossing the

boundaries between the two reminds us that the artist-subject is also dependent

on the time of others, that the artist is in a state of decay and imperfection,

and, as a result, that he can only survive by being captured and occupied by

others. He proposes the phrase “Who will care for our

caretakers?” by American lesbian poet Pamela Sneed as

the title of his Korea Artist Prize 2023 exhibition. Written while

having her colleagues pass away during the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s,

the sentence looks beyond the perspective of the mourning survivor to recognize

that the mourner in the here and now can also be someone else who will die damaged

at any moment. It passes through the challenge of the time to rethink—beyond the one-sided memory of a single party—a shared life lived, mutual care, tangled care that surpasses the

care system and the care industry, and the social structure of care for sharing

the anxieties of life around poverty and aging beyond the exclusive family

model.

In an interview for the Korea Artist Prize 2023, Kang Seung

Lee described himself as a messenger. This somewhat qualifying expression

asks that he examine what languages he needs to master in order to connect

different times and regions, and what devices he needs to employ in order to

articulate and secure a life worth living. It goes beyond compiling records and

reference materials and organizing exhibitions, and asks him to take up the

position of a director who re-invents gestures from the past that have not been

given meaning, and to then make them appear on stage. Furthermore, contemporary

collaborators and colleagues are asked to provide an opportunity where

co-creation can continue to generate discussion and discourse based on

cross-reference and coordination. This suggests that the work of remembering

and the work of unlocking time can happen simultaneously. A more perceptive

reader may even recognize that this act of unearthing and connecting has been

described as queer temporality, but it is not so different from the practice of

democracy.

Kang Seung Lee put the images of shame at the forefront. Those

people who were constantly “discovered” or “caught” in the

titles described with revelry and disturbance, and who could easily evaporate

as objects of “reportage,”

instead appear in the limelight. The image he put on the forefront of the

exhibition is that of a group of people who, in the face of a violent outside

gaze, were decorating themselves in a dark place at night very disturbingly,

and left behind the image of themselves as if for commemoration. Of course,

society would not have perceived the decorations they wanted to show off as

harmless. Considered perverted, disturbing, and not to be seen in public, they

were constantly subjected to crackdowns and gossiped about, but in the end, they

refused to give up their expressions and performances and kept themselves

attached to the screen on which they were performing. It is not a jump in logic

to interpret this as a hope and a sign of fragile connection amidst struggle,

degradation, isolation, and a legacy of gardening that each of them must have

cultivated. The attempt to push his work based on memory and collection into

the possibility of radical care leads to an attitude of collaboration which

presupposes that—like those who mourn, discover

something for mourning, and have difficulty remembering someone fully—one’s work is dependent on the traces of

others. Calling on colleagues and devising attempts to reproduce the programs

of community may very well be the efficacy of the art that Kang Seung Lee has

maintained throughout his career.

The impossible attempts to convey the temperature of one’s unreachable body exceeds the artist’s

capacity as a subject. At the same time, however, these attempts connect

through him. He continues to create and devise places to create a time to come

and a time to open up, finding colleagues and connections along the way. While

walking through the thoughtfully collected and rearranged exhibition, I

consider the forms of aesthetic touch that the artist has been devising, and

think how and to whom this time will open or close.