Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

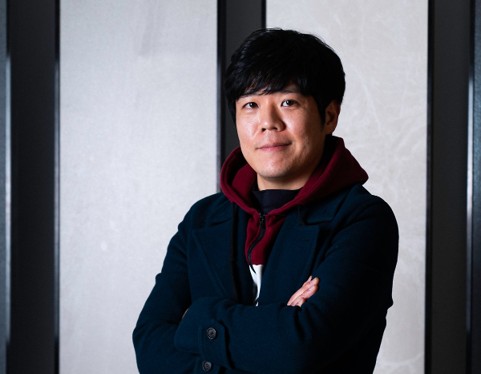

Beak Jungki has held 12 solo exhibitions from

2006 to 2023 at institutions including Alternative Space LOOP (Seoul, Korea),

OCI Museum (Seoul, Korea), and Doosan Gallery (Seoul, Korea; New York, USA).

His exhibitions 《Contagious Magic》(2019, OCI Museum, Seoul,

Korea) and 《Revelation》(2015,

Doosan Gallery New York, New York, USA) have been recognized for exploring

materiality and spatial transformation through experimental sculptural

language.

His recent solo exhibition 《All in One》 at ARARIO GALLERY (Seoul, Korea) in 2023 continues to investigate

the intersection of public and private experiences, proposing unique spatial

compositions through the physicality of materials.

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

Since

2004, Beak Jungki has participated in numerous curated exhibitions at major

public art institutions, including National Museum of Modern and Contemporary

Art (Gwacheon, Korea), Seoul Museum of Art (Seoul, Korea), Amore Pacific Museum

of Art (Seoul, Korea), Ulsan Art Museum (Ulsan, Korea), SongEun Art Space

(Seoul, Korea), Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art (Seoul, Korea), POSCO Art Museum

(Seoul, Korea), and Daegu Art Museum (Daegu, Korea).

Internationally,

he has exhibited in Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany, the UK, Italy, the US,

Venezuela, Israel, China, Hong Kong, and Singapore at institutions such as

Saatchi Gallery (London, UK), Hermitage Museum (Saint Petersburg, Russia) and Beijing

Commune (Beijing, China).

Recent key

group exhibitions include 《The First Here, and the Last on the Earth》(2024,

Oil Tank Culture T1, Seoul, Korea), 《Whose Forest,

Whose World》(2024, Daegu Art Museum, Daegu, Korea), and

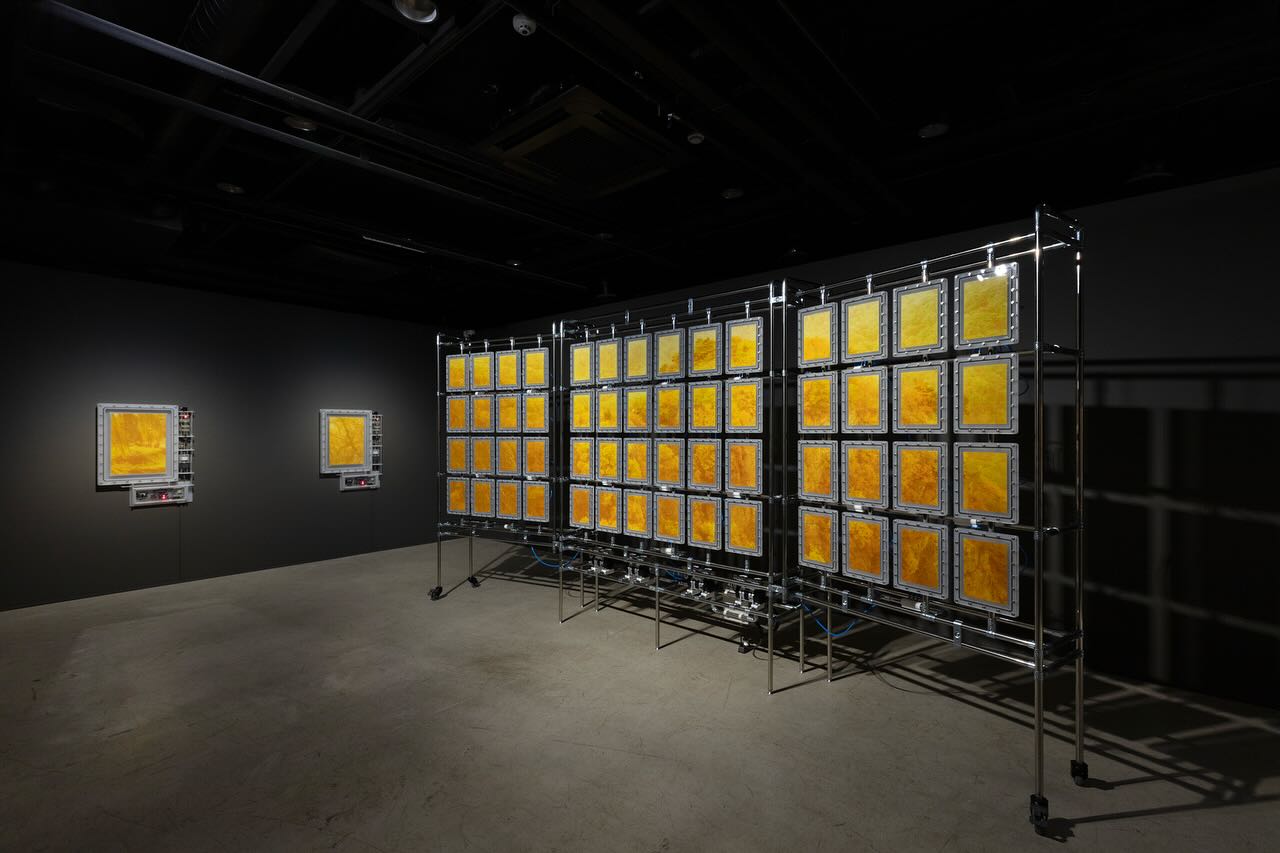

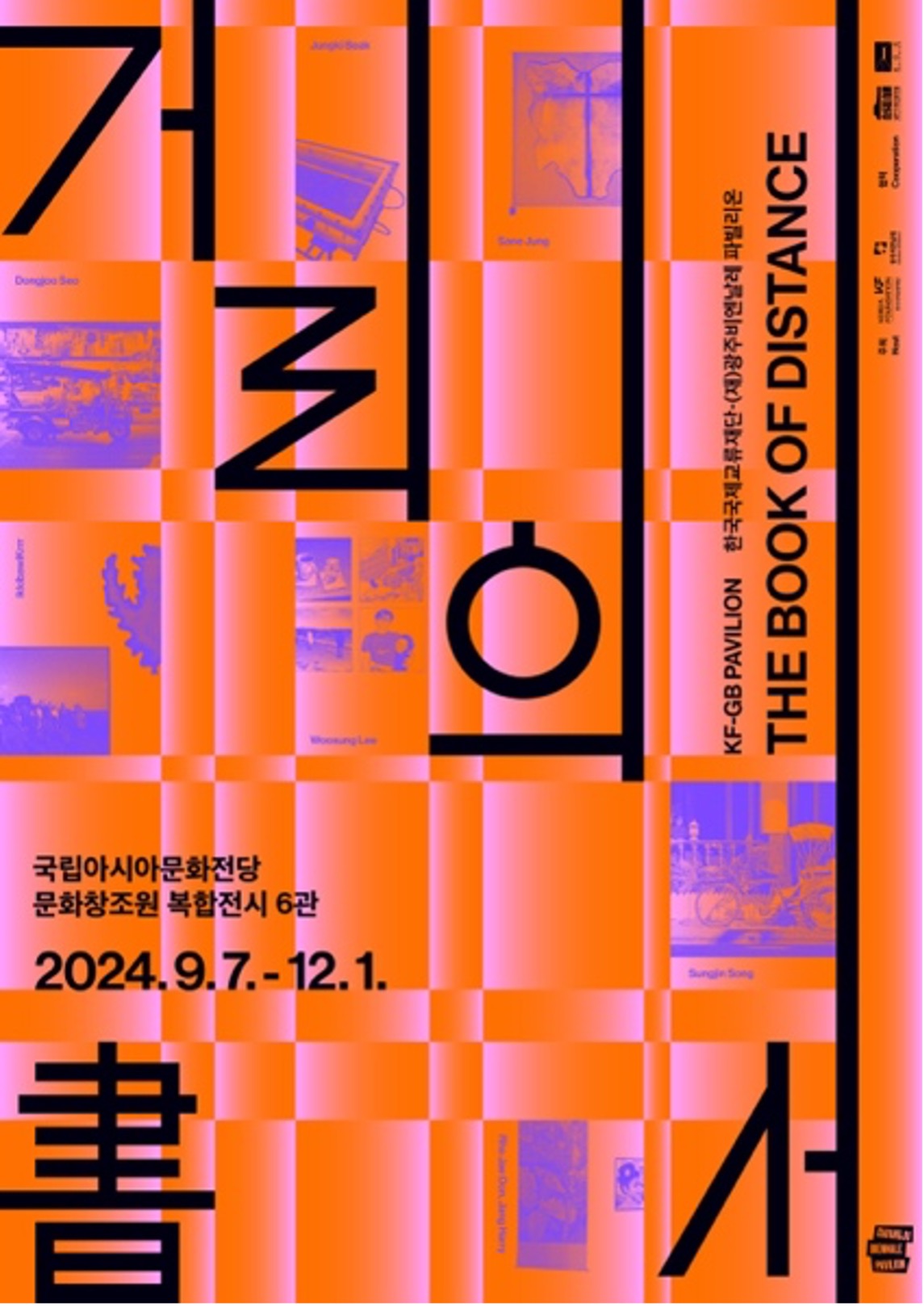

《The Book of Distance》(2024,

National Asian Culture Center, Gwangju, Korea).

Awards (Selected)

Beak Jungki gained recognition in the art

world after receiving the Songeun Art Award (2012, Seoul, Korea). In 2019, he

was awarded the 30th Kimsechoong Art Prize (Seoul, Korea), further solidifying

his status in the fields of sculpture and installation art. Most recently, he

won the 28th IFVA Media Art Gold Award (2023, Hong Kong Arts Centre, Hong Kong,

China), reinforcing his international reputation.

Collections (Selected)

Beak Jungki’s works are housed in the

collections of major institutions, including National Museum of Modern and

Contemporary Art (Korea), Museum of Contemporary Art Busan (Korea), Ulsan Art

Museum (Korea), ARARIO MUSEUM (Korea), Doosan Art Center (Korea), OCI Museum

(Korea), SongEun (Korea), and Bridge Guard Art & Science Center (Sturovo,

Slovakia).