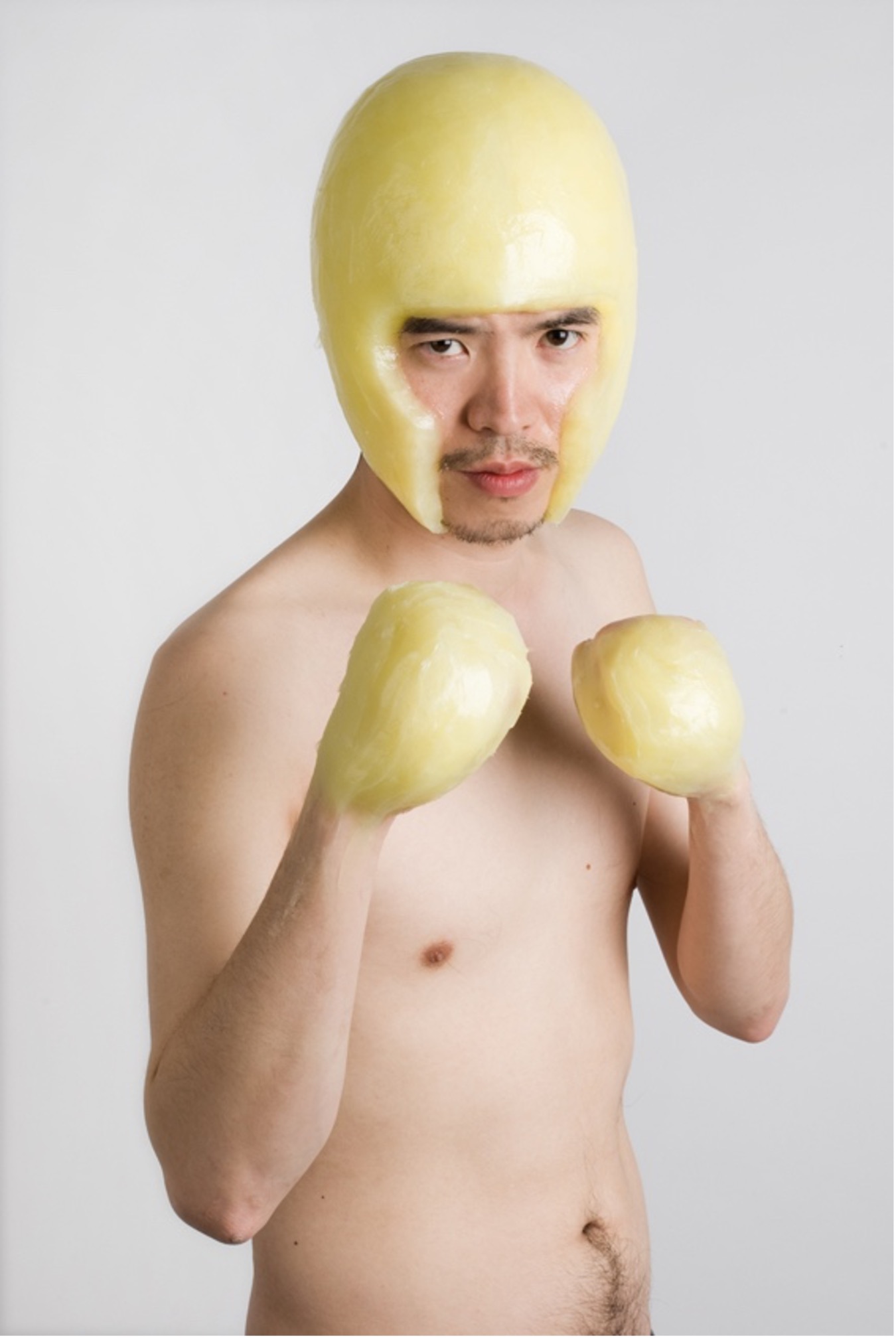

The ‘Vaseline’ (2007) series, which appears to stem from Beak’s

childhood experiences—such as a fire-related finger injury and its subsequent

medical treatment, as well as the trauma linked to his father’s punishment and

love—is not based on Vaseline’s actual therapeutic purpose and efficacy.

Rather, ‘Vaseline’ represents what people want to believe about the substance,

reinforcing psychological reward mechanisms and illogical beliefs instead of

confronting objective facts. The series features large quantities of Vaseline

applied thickly onto heads, hands, and even the indentations of walls, sculpted

into specific forms such as helmets, gloves, or patches. The work grants the

viewer an unfounded belief that the art itself can heal the weak, the injured,

wounds, deficiencies, and voids, despite the fact that Vaseline’s softness

makes it completely ineffective as protective gear.

Next, Pray for Rain-Morocco (2008) is even more

explicitly magical than ‘Vaseline.’ In the Sahara Desert, where rain is

virtually nonexistent, Beak melted a Vaseline sculpture of a lizard*,

re-sculpted it into a compass, and ultimately let it evaporate into the

sky—equating this entire process to a "rain ritual." Through this

work, he took on the role of a shaman attempting to resolve the socio-political

conflicts historically and ethnographically experienced by water-scarce

regions. What about the perspective of the audience? In this work, which can

now only be viewed through archival video recordings, the audience might, like

the artist, believe in art’s magical ability to alter the climate and thereby

solve the chronic problems of a community. However, conversely, they may also

recognize the anachronistic aspects of the act when viewed through the lens of

objective reality or compared with art historical precedents, realizing that it

is nothing more than a metaphor.

One could examine the anachronism and the limitations of this

metaphor in a broader historical and conceptual framework. Joseph Beuys, a

quintessential example of the artist-as-shaman, used animal fat and felt in the

1960s-80s to mediate between the worlds of life and death, subject and other,

and the agony of annihilation and the ecstasy of rebirth. However, Beak Jungki,

as a contemporary young artist, attempts to mediate the gap between natural

order and human desire, as well as the fractures of social conflict, through

aesthetic symbolic acts reminiscent of past art forms, despite the

technological and ideological realities of the 21st century. At a time when

artificial rain can be generated anywhere through technological means and when

coexistence and mutual prosperity under globalization are believed to be

achievable solely through capital, Beak seeks to demonstrate the magical power

of art.

In fact, not long after executing Pray for

Rain-Morocco, Beak himself arrived at such critical awareness. He

began to reflect on whether his art was “nothing more than a performative

gesture (...) whether, as an artist, he was always performing certain actions

that ultimately remained mere artistic concepts or aesthetics.” As will soon be

discussed, this self-examination led him to move away from shamanistic

attitudes and methodologies, instead embracing a more scientific consciousness

and framework. He began to center his work on the fundamentals of science:

observing and analyzing objects, engaging with subjects empirically (through

use, interpretation, and composition), and actively incorporating

experimentation and mechanical processes into artistic creation.

At this point, what initially seemed anachronistic in Beak’s work

can be reinterpreted as cleverness. This cleverness is not merely about

recognizing the limitations and contradictions within his own work. More

significantly, whether by deliberate planning or incidental serendipity, Beak

initiated his practice from an artistic model, discourse, technique, and mode

of expression that diverged from contemporary conditions, thereby naturally

engaging with precedents in art history. Consequently, his work aligns with the

transitional and evolutionary nature of contemporary art.

2. Aesthetic Effects: Semi-Scientific and Semi-Artistic

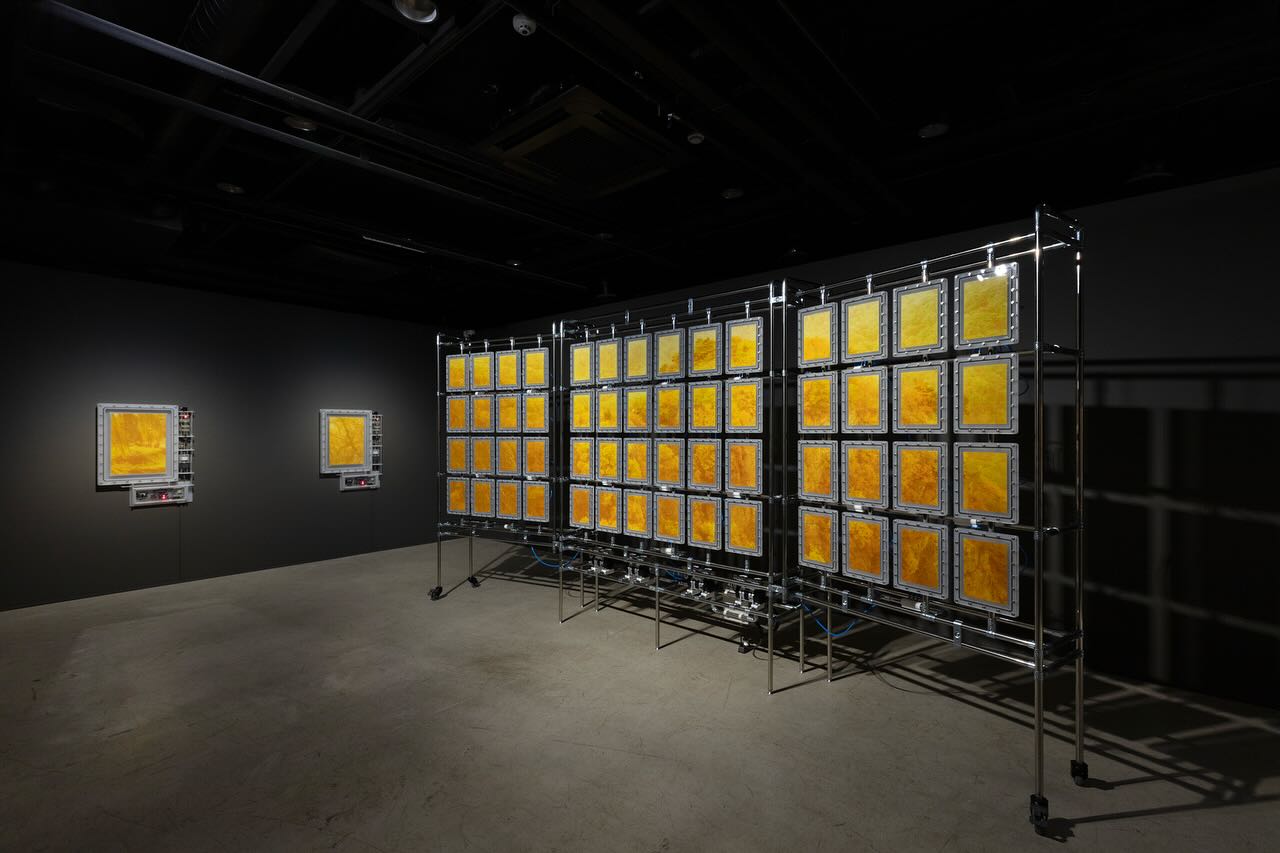

If one were to select the most empirically grounded work by Beak

Jungki, it would undoubtedly be the Is of series. The final

result of this series is photography, yet the images in these photographs were

astonishingly printed using pigments extracted from the very objects depicted

in them. For instance, a photograph of autumn leaves in Seoraksan was created

by collecting the yellow, red, and green leaves from the mountain, grinding,

pressing, and extracting their pigments using various devices, and then

printing the image with those very pigments. Similar to how people mistakenly

believe that banana-flavored milk is yellow or that flesh-colored crayons

originate from actual skin tones, this paradoxically logical Is

of series seems to prove that such misconceptions are not necessarily

erroneous. The decisive factor that made this series possible was the artist’s

repeated experimentation. Beak tested solvents and separators to extract

colors, modified a printer to print using raw plant extracts, and even

developed specific components to facilitate this process. Therefore, the

scientific aspect of Is of is not merely a conceptual

influence but rather an engagement with engineering—more specifically, the

theoretical and practical development of mechanical devices. However, since the

ultimate destination of these theories and practices is art—more precisely, a

singular artwork—the scientific nature of the work remains only partial.