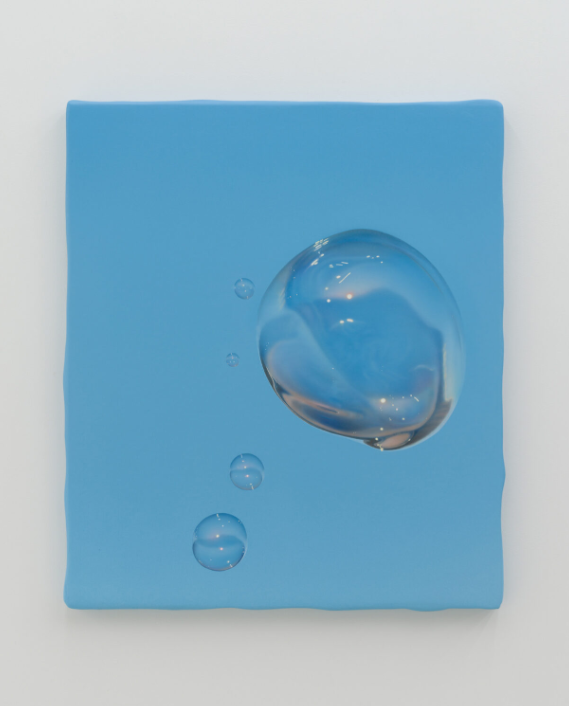

Transparent

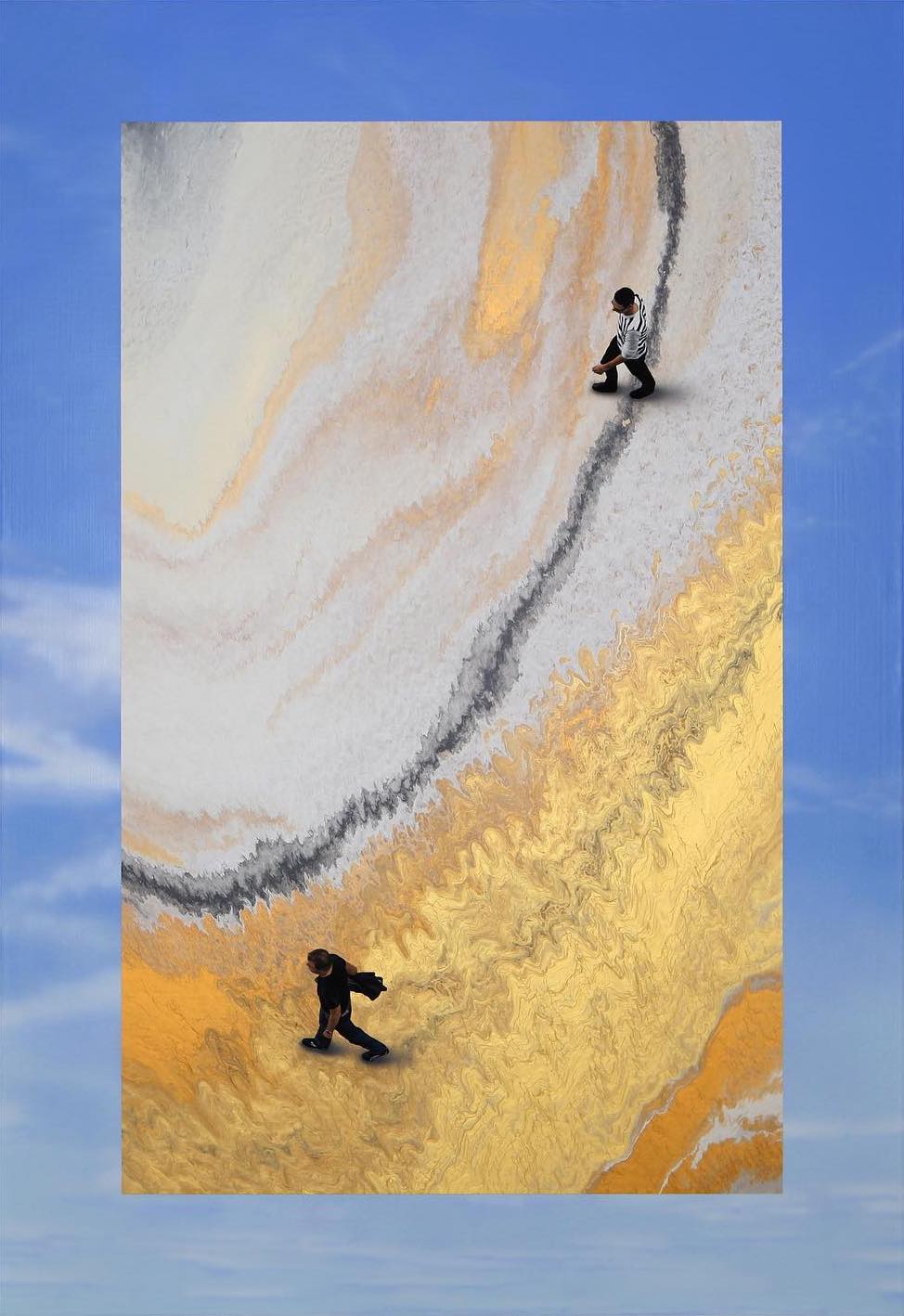

blue skies—sometimes tinged with sunset hues—are dotted with floating soap

bubbles. Some paintings capture shimmering ripples on the surface of water, as

if teasing light itself. Is this a landscape painting somewhat different in

texture from conventional ones—one that renders what is almost like empty

space, or water surfaces, at full scale, drawing the viewer entirely into that

void, into that surface? Upon closer inspection, one corner of the image curls

inward. There is a shadow cast by the curled section. Along the side or lower

edge of the picture—cut as if by a knife—there remain blank areas that appear

unfinished. Is it an incomplete painting? A photograph? A printed sheet affixed

to the wall?

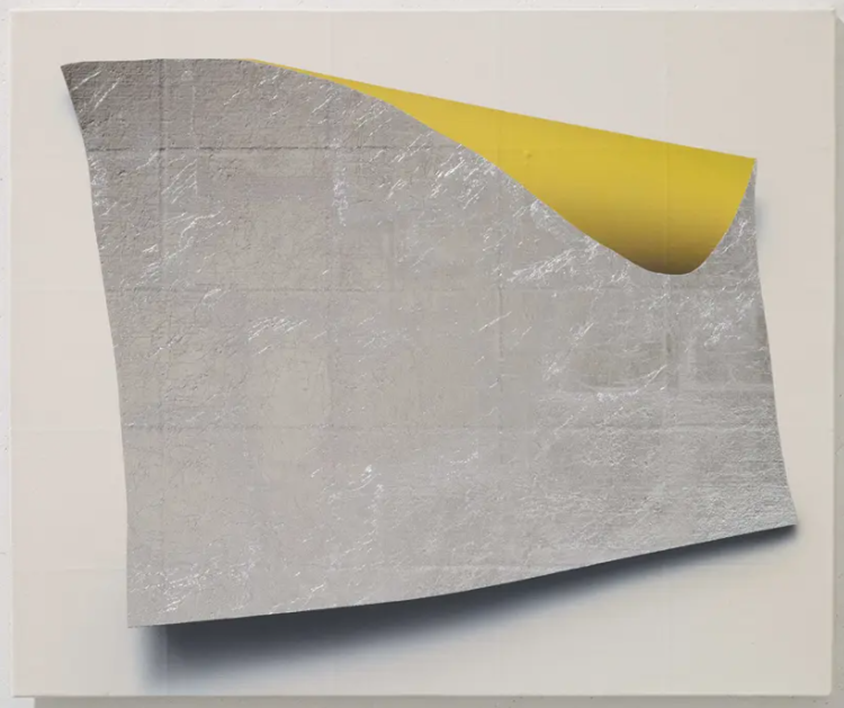

Looking

again, one notices that the background surface is constructed by joining

rectangular sheets of hanji cut to a uniform size. Where the sheets overlap, an

embossed relief emerges, and behind the printed image, fine surface

irregularities can be felt. Then is it an image printed atop hanji layered onto

a sheet? One cannot tell whether it is a painting, a photograph, a sheet, or a

printed image. Why, then, did the artist paint this unknowable image(?)

There

is also work in which colored sheets cut into rectangular forms are affixed to

the wall, naturally curling at the edges and casting shadows, with visible gaps

where the sheets lift away from the wall. Is this an installation that replaces

painting with objects? Conceptual art that foregrounds painterly flatness and

color fields? It is difficult to say. Although stated seriously, in truth there

are neither objects nor installations in the artist’s work. What appears to be

an object, an installation, or conceptual art all occurs solely within the

situation logic of the painting. Objects, installations, and conceptual art

alike unfold entirely within the representational logic of painting.

Borrowing

traditional and orthodox methodologies and grammars manifested through

representational painting, the artist proposes these various situation

logics—such as questions concerning the relationships, boundaries, and

differences between reality and represented images, or between reality and

illusion. In this sense, Seong Joon Hong fulfills the definition of art as a

technique of questioning: by asking what representational painting is, what

representation is, and what painting itself is. Asking the self through the

self, questioning painting through painting, questioning representation through

representation, and questioning critique through creation—this is the enactment

of conceptual art.

Maurice

Denis stated that a painting, before being a battle scene or a nude, is

essentially a flat surface covered with colors, that is, a color plane. Clement

Greenberg argued that the essence of painting lies in flatness and advocated

Color Field painting, where flatness and color planes converge. These

statements, originating from the modernist paradigm that questioned the essence

of painting, later prepared the ground for conceptual art (and minimalism),

which shifted the object of painting from a sensory to a logical and semantic

domain. Marcel Duchamp, through the readymade, and Andy Warhol, through

reproduced readymades, replaced painting altogether, dismantling the boundary

between art and object, and between art and everyday life—developments that

would later serve as the basis for Arthur Danto’s declaration of the end of

art. Though differing in nuance, all of these share a self-reflective inquiry

into what painting is and how it functions.

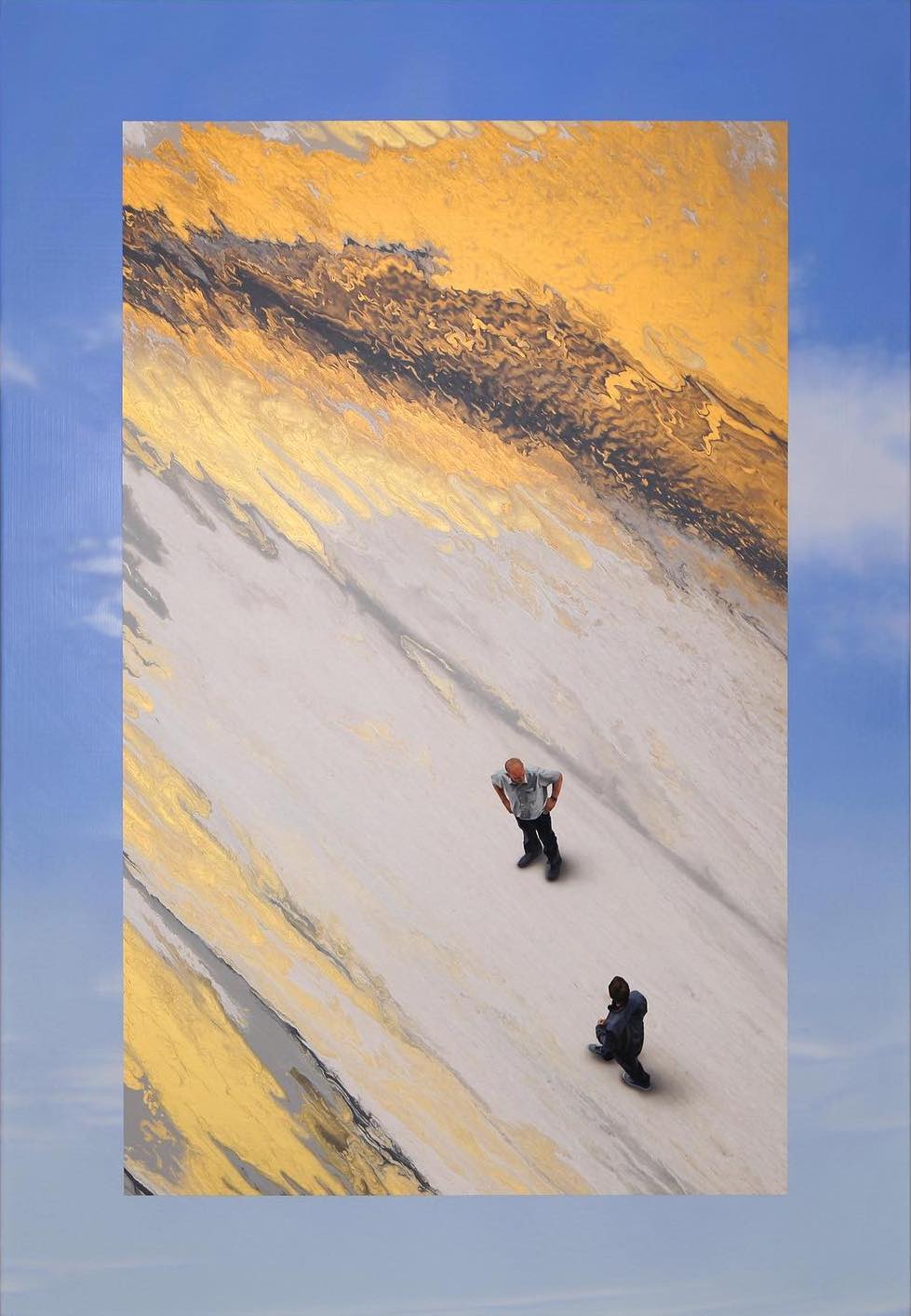

Into

this lineage, Seong Joon Hong proposes the notion of layers—of overlap. The

essence of painting is layering. Overlapping touches of blue and red generate

illusions that resemble skies, sunsets, rippling water surfaces, or glimmering

particles of light dancing upon water. Through such representational

images—images that only appear to be representational—the artist foregrounds

flatness, foregrounds layers of color planes built through color upon color,

and foregrounds the objectified form of overlapping touches. If the modernist

paradigm invoked flatness and color fields to question the essence of painting,

might it be said that Seong Joon Hong re-summons that essence through

layers—through overlap itself? Yet it remains unclear how layers differ from flatness

or color fields (setting aside readymades and reproduced readymades). Perhaps

it is precisely this lack of clarity that opens up the possibility for

unexpected directions to emerge.