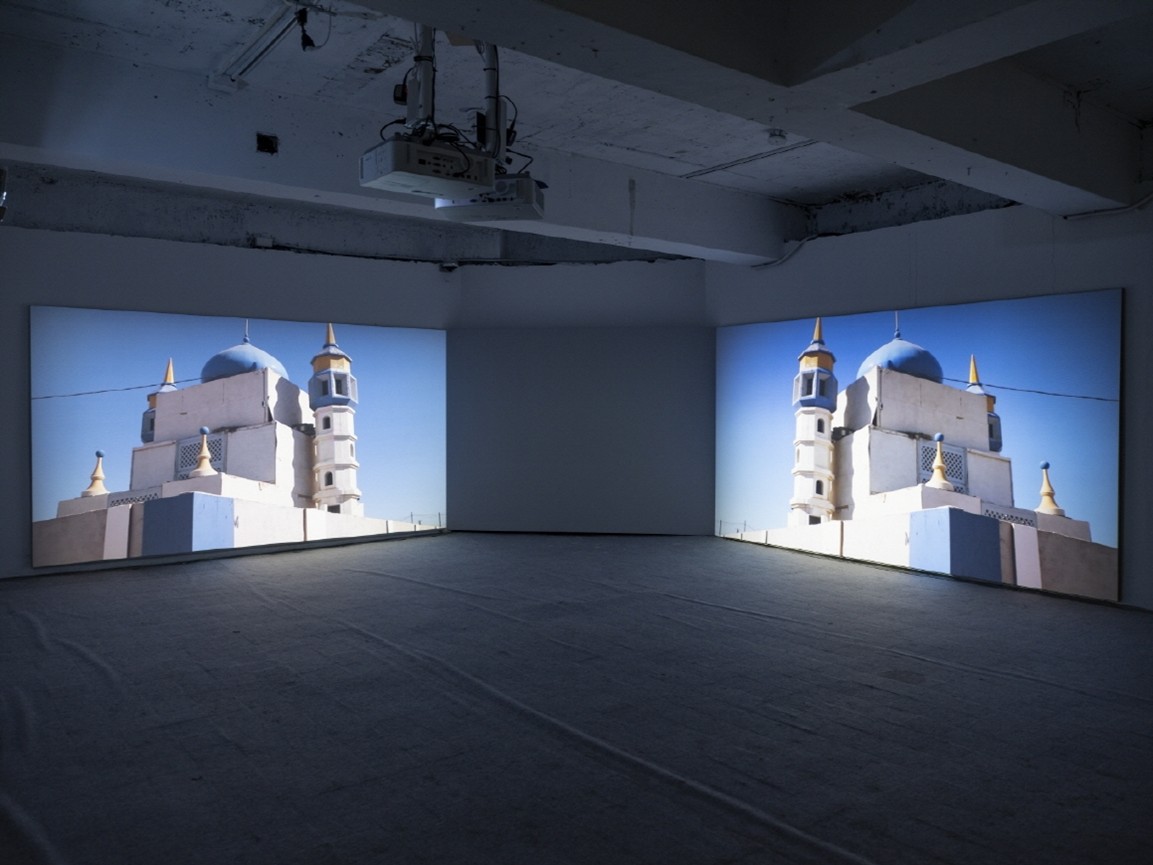

The

collective METASITU’s video work takes its title, Tora Bora,

from a term used to describe the dust that accumulates on the skin and bodies

of Palestinian laborers working in Palestinian quarries. The limestone—also

known as “Jerusalem stone”—extracted, processed, and exported by these laborers

has long materialized Israeli religious ideology, used to establish a state on

Palestinian land and to push Palestinians into a colonial condition.

The quarry

and stone-processing factory scenes composing Tora Bora do

not present melancholic ruins or scenes of mourning; what we witness is the

production of materials destined for the altar of the occupying force. In this

sense, the quarry dust recalls the urban landscapes of Osaka and Yokohama in

the films of Masao Adachi, who articulated the theory of landscape (Fûkeiron).

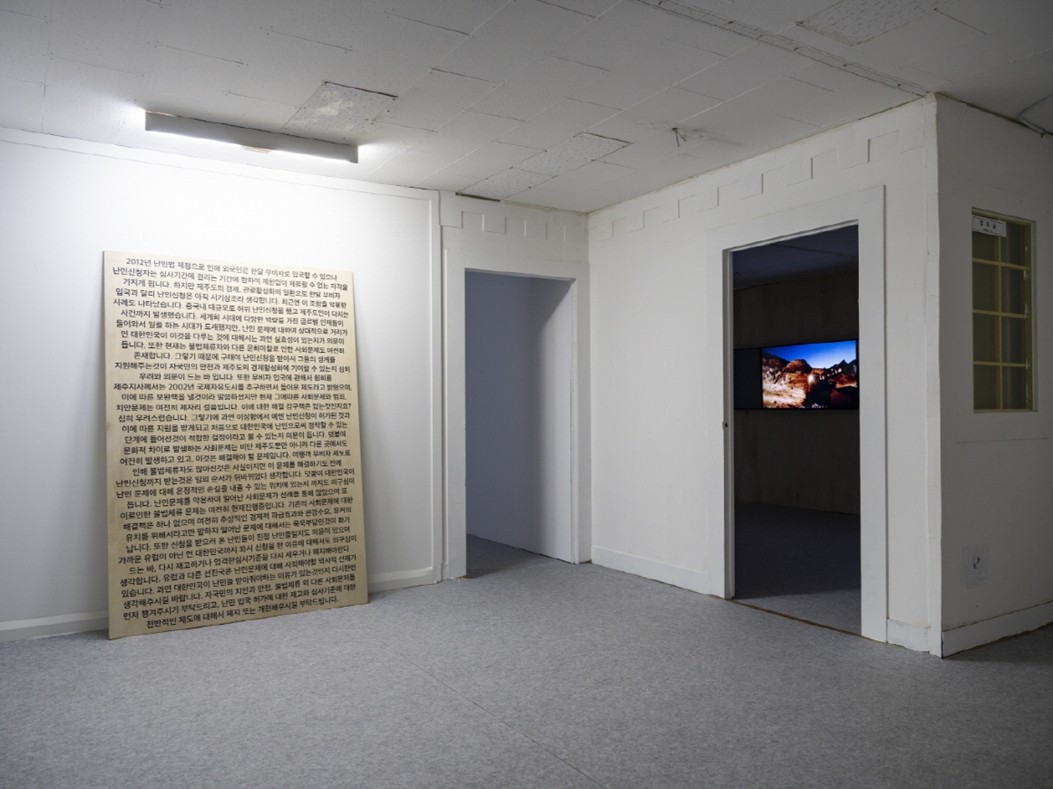

Passing

photographs of Hyundai Construction Equipment excavators used in Israeli

settlements and archival presidential speeches revealing aggressive sales

ambitions toward the UAE, viewers arrive at the prolonged duration of Yeoreum

Jeong’s video work To the Innate Witness, running eight

hours and fifteen minutes. Like the works of Lee, Park, and METASITU, Jeong’s

work is grounded in the contexts of war, conflict, and colonialism, and is

mediated through questions of media. While Park explores war through the lens

of perceptual imagery, Jeong approaches war through its relationship with

media. This thematic concern was already prominent in her earlier works Graeae:

A Stationed Idea and The Long Corridor.

In To

the Innate Witness, the images Jeong endlessly collects—while

remaining connected to the internet, that is, to the spatiotemporal field of

conflict—are videos uploaded by Gaza civilians themselves as airstrikes unfold.

One could readily speak of the significance of Jeong’s archiving practice,

noting her attentiveness to the archive’s capacity to “unexpectedly open onto

unknown worlds,” to offer “vivid preliminary sketches for reinterpretation,”

and to release unforeseeable “reality effects.”⁴ Yet unlike her earlier works,

in which she assembled clues about the operations of unmarked U.S. military

bases, To the Innate Witness delivers the time of

a disaster-stricken world directly before the eyes of witnesses who cannot

avoid being witnesses within today’s media environment.

Does

this work, by presenting unprocessed archives, seek to make contemporary

viewers experience desire and suffering firsthand? The sounds of shells,

darkness, flashes of light, crowds moving without certainty toward refuge, and

images of Gaza in daylight fill videos lasting one hour and thirty minutes, or

eight hours and fifteen minutes. Voiceovers—aftermaths or parables of violent

societies—are woven into the images, often betraying their temporality.

More

than the content of the archive itself, Jeong’s work seems to question the time

spent mining and viewing archives: the time of action, the time of the body,

and the emergence and unfolding of emotions and numbness that adhere to and

eventually overtake the body. Rather than experiencing the time of disaster, we

experience the time of the witness, observer, and spectator—where desire and

ethics sharpen, shaped by anticipation and expectation.

This

is the nature of the experience proposed by the exhibition 《My Fellow Citizens》: to experience a time of

ethics without ethics, and to remember it as a time of conflict in which ethics

must be reestablished from the ground up.

Notes

1.

Ichiro Tomiyama uses the term “interrogation space” to describe spaces

permeated by linguistic violence in which state institutions question and

forcibly extract answers, drawing on Frantz Fanon’s critique of colonialism.

Ichiro Tomiyama, trans. Jung Myung-shim, Knowledge of Beginnings: Frantz

Fanon’s Clinical Thought, Moonji Publishing, 2020.

2.

Paul Virilio refers to the era following World War II—characterized by nuclear

deterrence and generalized civilian anxiety—as the era of “total peace,” a term

that also denotes total war disguised as peace. “Pure war” is closely linked to

total peace but more directly connected to scientific development, referring to

a state in which science and technology eliminate contingency and assume

omnipotence. Paul Virilio, Défense populaire et luttes écologiques, Paris:

Galilée, 1978; L’insécurité du territoire, Paris: Galilée, 1993.

3.

Serge Daney, La maison cinéma et le monde-2. Les années Libé, 1981–1985,

Paris: P.O.L, 2002.

4.

Georges Didi-Huberman, Images Malgré tout, Paris: Éditions de Minuit,

2003.