One autumn, I visited the clock tower of a hospital where a family

member had once been admitted. The tower’s machinery took up three of the

building’s five floors. Its clock weight, wound every four days, descended

slowly to drive the rollers—a mechanism that required nearly ten meters of

space. Narrow, steep wooden stairs. A small attic door, so low you had to bend

your knees and bow your head to pass through.

Pulleys hanging from a ceiling so

high it seemed endless. A pendulum resting at the bottom. Light poured in

through the glass windows on all sides, almost blindingly bright, yet it was

the deep, dark silence of the motionless machine that pulled me in. The

disquieting stillness of the clock tower stayed with me. And it abruptly

resurfaced when I encountered Hosu Lee’s work.

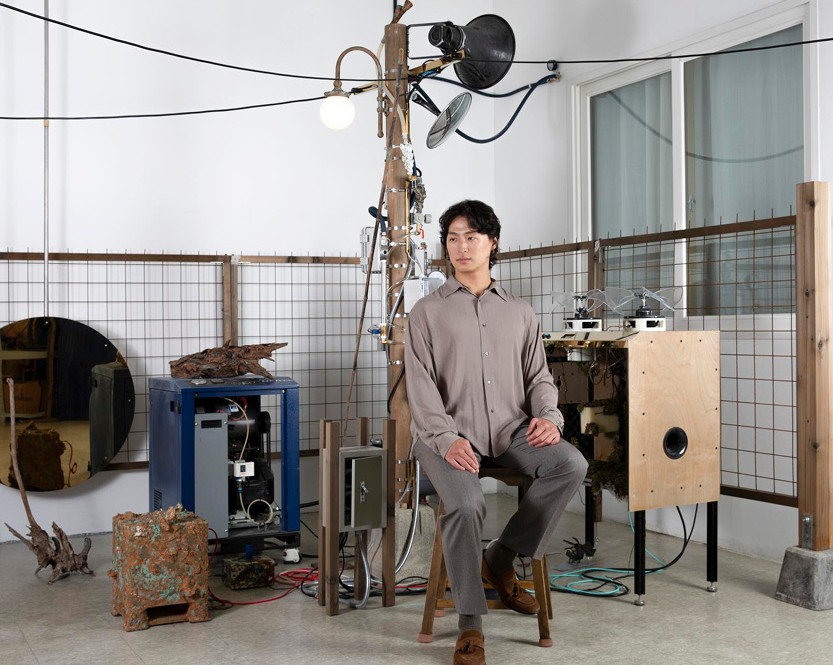

At the core of Lee’s practice is a pendulum, one that “longs to

move on its own.” In conversation, he shared that over the past eight years, he

has explored the pendulum’s material and form through his ‘Time Machine’

series—shaping it into concrete swings and stainless steel grandfather

clocks—at times combining them with sound and light-sensing systems to probe

the sculptural and the systematic. Like a heartbeat setting blood in motion,

his pendulum-driven structures seem to have generated their own temporality and

rhythm within the exhibition space. I wondered what had drawn him so deeply

into the world of the pendulum. But rather than offering a single answer, he

draws the viewer into its hypnotic motion, an experience of time in flux.

In his solo exhibition 《Time And

Machine》 at OCI Museum of Art, Lee

expands on this exploration, treating the exhibition space itself as a

sculptural body. If his previous shows allowed viewers to observe each work

from a distance, here, sculpture becomes a situation, drawing viewers in. The

first encounter is with a massive pendulum, its large, round, reflective

stainless steel surface moving with deliberate grace. It mirrors us, but what

Lee wants us to see lies beyond the surface. Like Alice shrinking down, we step

past the clock face, beyond numbers and hands, into something deeper, darker.

The contrast between inside and outside unsettles us, enough that we might

slip. And then, we land.

It is dark. And unexpectedly, we are outside—a landscape devoid of

people. Something has vanished, yet something else emerges in its absence—what

Jean-Luc Nancy called “the sudden appearance [...] of the one disappearing.” A

utility pole. An outdoor unit. A compressor. A storage container. A fence

enclosing them, barring entry. The scene isn’t dystopian in any contrived way;

if anything, it is so familiar, so ordinary that it feels like the present.

Beneath the polished surfaces, the unkempt machines run on, as if they were

always part of the natural world. It’s the eerie feeling of climbing a hill you

never knew had a path and looking down at your home, now strangely unfamiliar.

The outdoor unit suggests there is an inside somewhere, but we are left outside.

Perhaps these machines have something to do with the pendulum we saw earlier.

Still, we remain outside. The air is cold, barren. It is both a landscape of

someone’s inner world and an exterior scene glimpsed on the way home. The

machines hum, deep and steady, filling the silence where people once were.

As our eyes adjust to the darkness, a small video comes into view,

tucked beside the outdoor unit. A pine tree sways in the wind. A gaze lingers,

fixed upon it. In an era where electricity is both nature and the lifeblood of

machines, only the tree remains truly natural, the voice we hear the only human

one.

“...in the end, we all have to say goodbye to each other. And it’s

not just about people. It is about places and things as well. Everything fades

away, withers, and eventually disappears, never to return. In fact, the entire

world [...] [and] our universe will vanish into nothingness.”

A nihilist’s confession, it seems. But then, another voice:

“...nothing ever truly fades as it seems, and everything remains

just as it is. Changes are illusions…”

How do we reconcile these two opposing statements?

Edwidge Danticat, writing about literature that grapples with

death, observed that writers create stories of death to make sense of it. This

video, then, feels like both a pre-written obituary—whether for himself or the

planet—and a refusal to stop creating. Creation as a long detour, wrestling

with the meaning of time left, searching for hope in what fades. Perhaps this

is why Lee has spent years fixated on the motion of the pendulum. His past

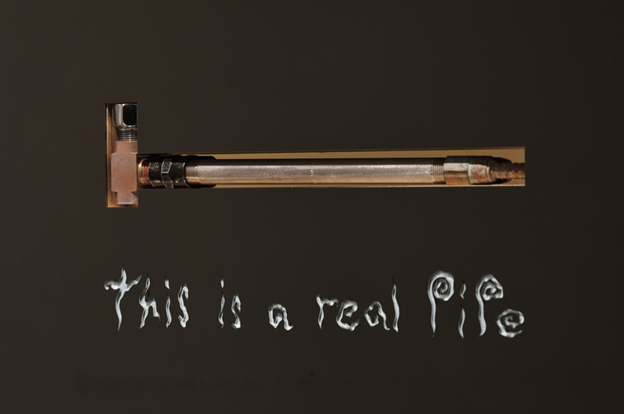

works have often incorporated text alongside sculpture—Manifestation,

a poem reassembled on a physical object, and Dream Manifesto,

inscribed on paint resembling rusted iron, both echo the voice in the video. A

body that vanishes, a body that remains. What changes, what holds.

The conjunction ‘And’ in the exhibition’s title, 《Time

And Machine》, invites us to linger on the

relationship between the two. To follow this thread on my own terms, I want to

bring in two seemingly unrelated things: yoga and music. In yoga, the body

moves from one asana to the next in continuous flow, each transition guided by

breath. A body becomes a desk, then a downward-facing dog, then a tree, then a

pigeon with an open chest, then a triangle.

The movement of the machine we call

a body generates flow and energy. (Not to mention that Lee’s pendulums, too,

move by air pressure, as if the machine itself were inhaling and exhaling.) In

music, sound and time are not separate, nor does sound merely occupy time.

Instead, notes push and pull at one another, one setting off the next like

dominos, forming melody. Imagine the black, round notes on sheet music as

punctures through which a needle pulls a transparent thread. That thread weaves

through the holes, and what moves along it is what we call melody. The motion

of sound creates time, a flow.

The ecological theorist Timothy Morton introduces the term

‘hyperobjects’ to describe entities that exist beyond the scale of human time.

He writes that, in an ontological sense, the future of the future is beneath

the past. In other words, time is nonlinear, stratified, and experienced in

potential. If Time And Machine is futuristic in any way, it is in how Lee’s

pendulum never settles—forever oscillating between inside and outside, essence

and appearance, opening up an unfamiliar sense of time.

‘Time And Machine’

takes the two words that form “time machine” and splits them apart, wedging an

‘And’ in between. In doing so, Lee moves away from the idea of machines as

vessels that transport us through the past and future as fixed points. Instead,

he suggests that time and machine were never separate to begin with; it is the

machine’s motion itself that generates time—reshaping it, making us feel its

presence.

We each have a sense of the abyss we long to reach—we have already

seen it. That day, climbing the carpeted wooden stairs of the clock tower, I

was searching for the time my family drifted through. So, if you, too, have a

quiet longing for something deeper, I hope you step into 《Time

And Machine》 with that desire. Lee invites

us to descend further into the dark, to find that what we left behind is still

there, still moving. His pendulum breathes, and in its motion, it reflects us

back.

*This essay was written based on conversations with the artist

during the preparation of his solo exhibition, 《Time

And Machine》.