Exhibitions

《We Go》, 2024.03.20 – 2024.04.20, DOOSAN Gallery

March 20, 2024

DOOSAN Gallery

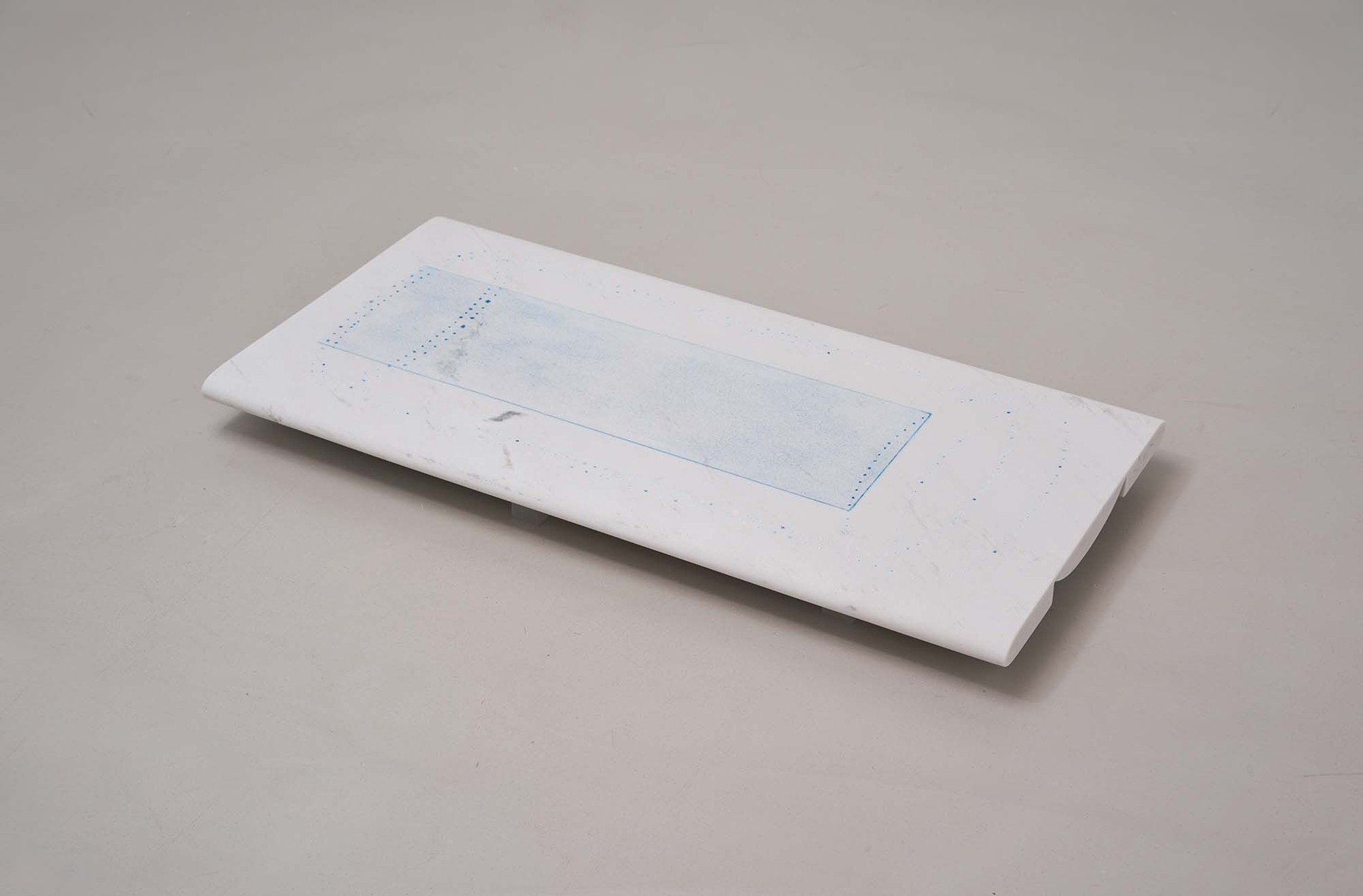

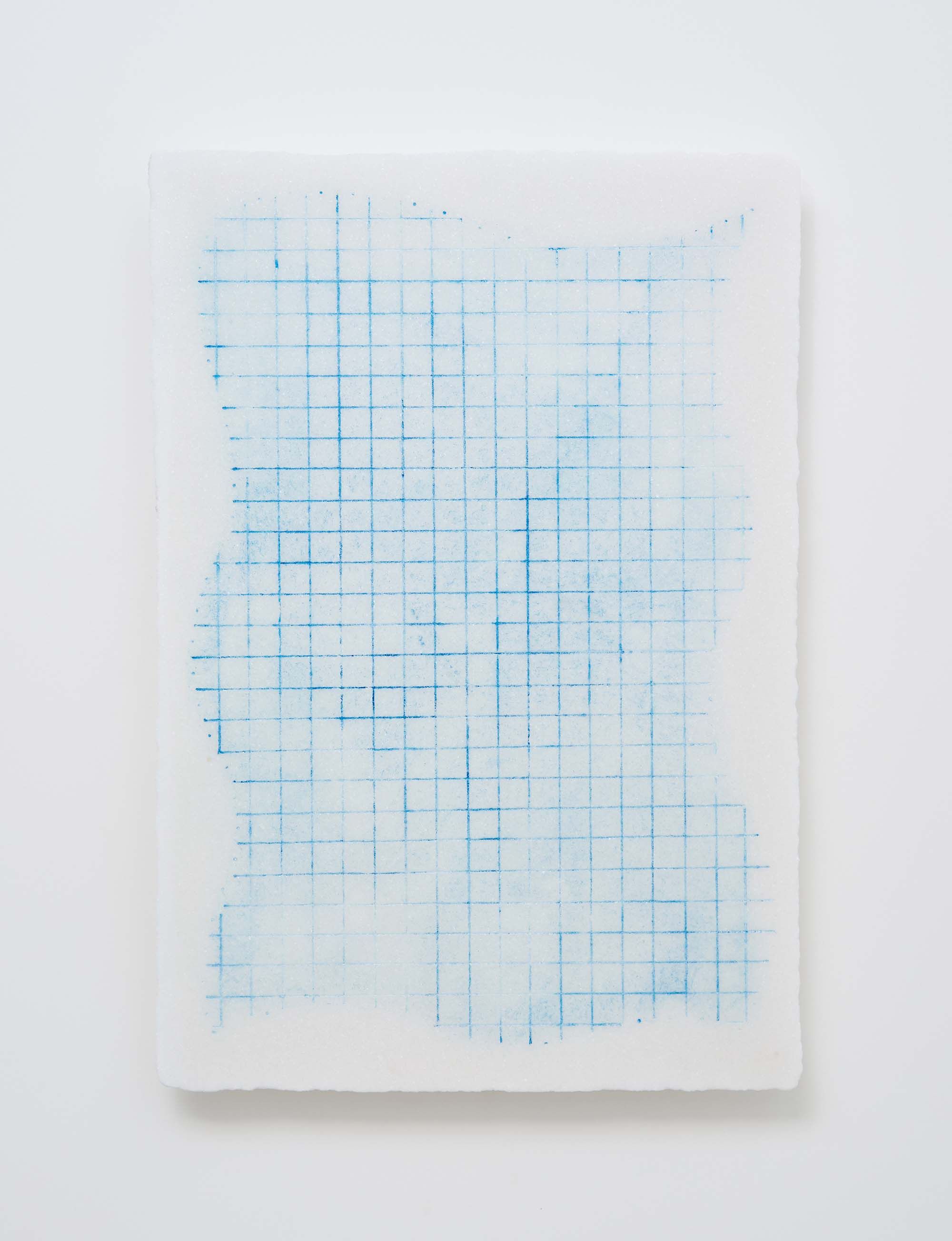

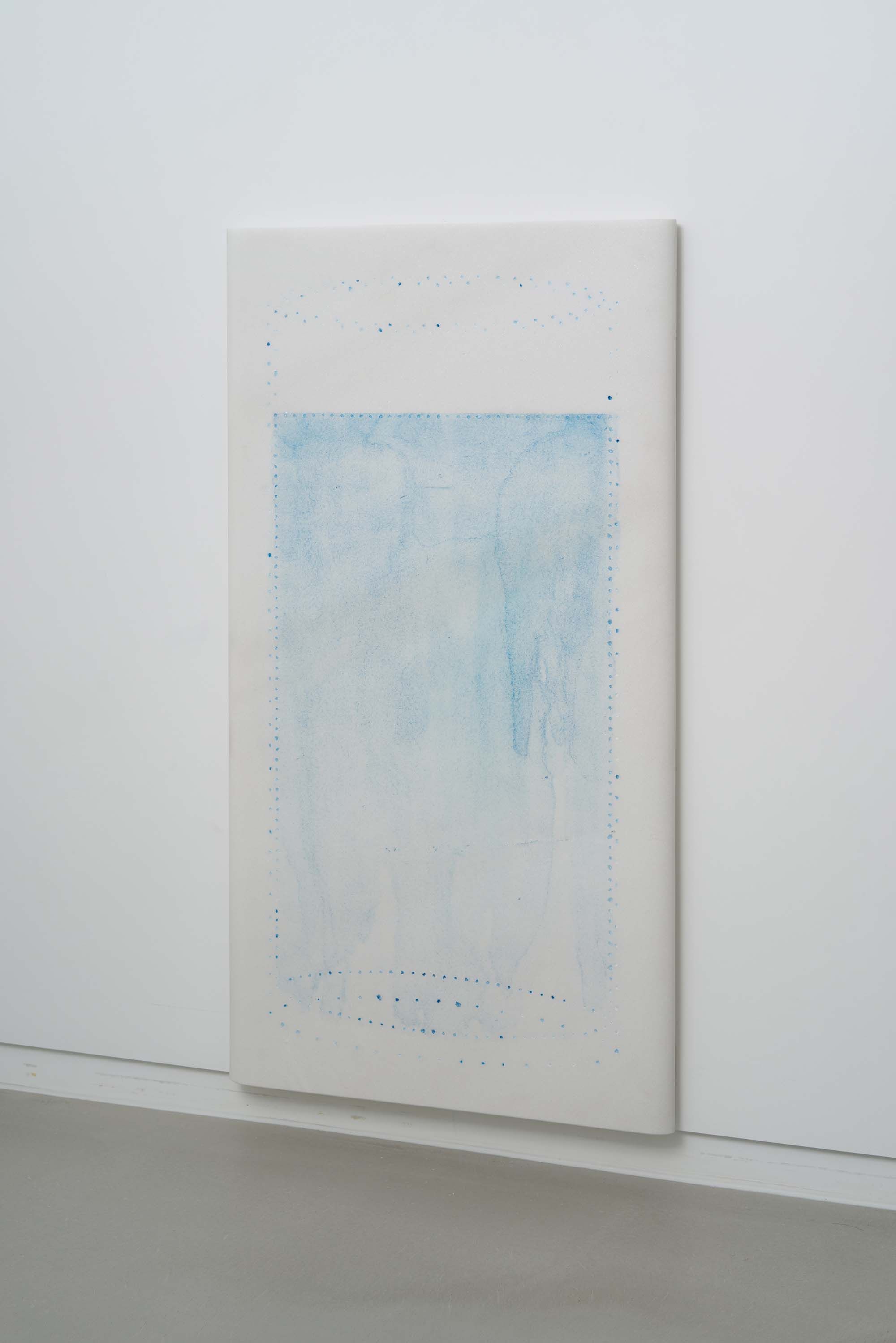

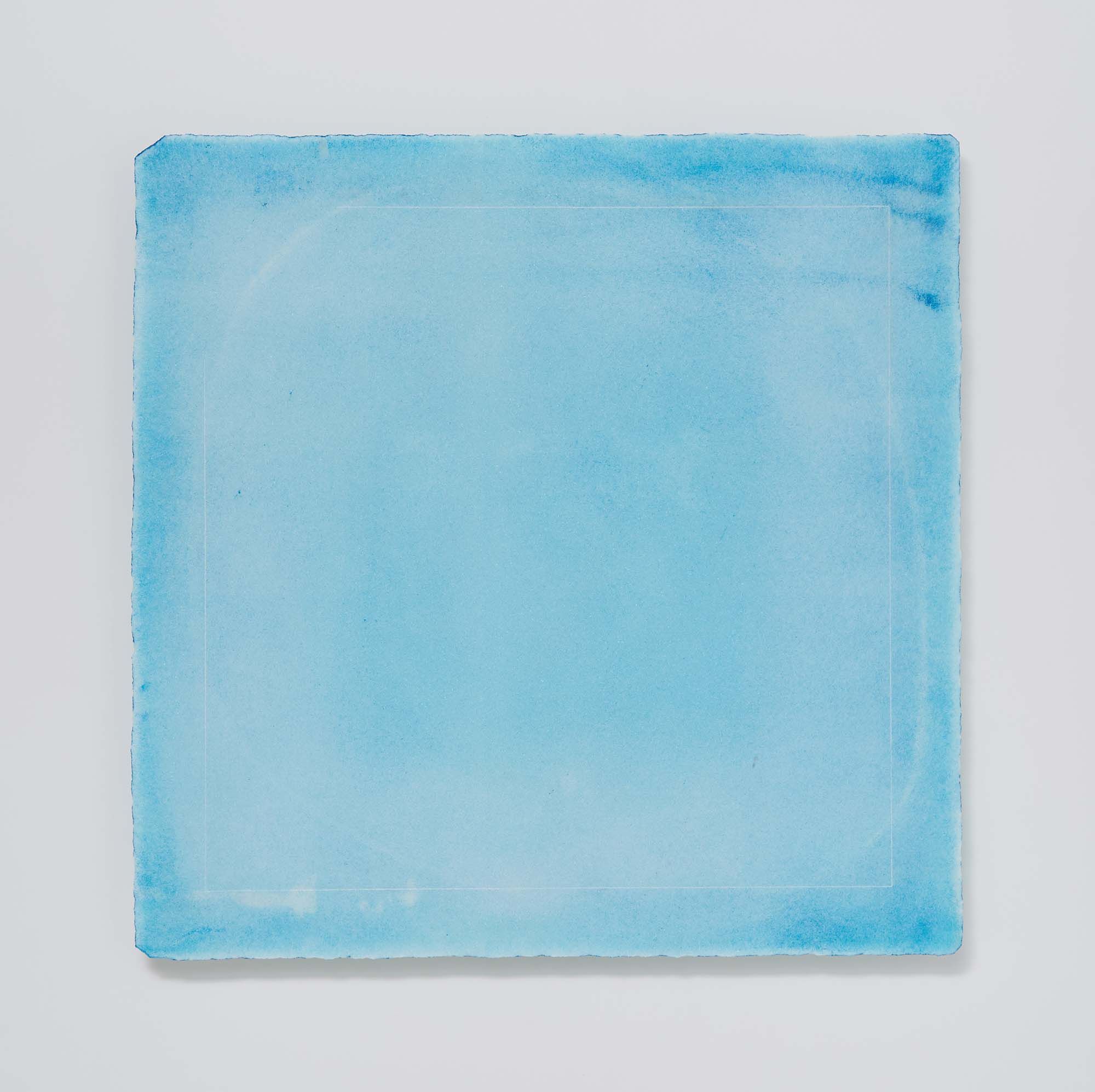

Installation

view of 《We Go》

(DOOSAN Gallery, 2024) ©DOOSAN Art Center

Kwon

Hyun Bhin’s solo exhibition, 《We Go》, envisages movements of objects

that have seemingly come to an end. In the title, “we” encompasses the various

subjects that a sculpture involves, and “go” represents the many kinds of

movements that a sculpture necessitates. Identifying these often requires a few

shifts in timeline and adjustments in spatial distance.

Installation

view of 《We Go》

(DOOSAN Gallery, 2024) ©DOOSAN Art Center

Kwon

regards her sculptures as traces of time—that the past, present, and future of

a material culminate in the sculptures. Working primarily with stone, she

tracks down the weakest spot. She observes it for a long time, discovers the

very spot where the stone willingly cracks open, then taps, carves, and

conjoins the pieces.

The lines, planes, and colors on the stone sculptures

might suggest intent, but they are closer to traces of Kwon’s time spent with

the material. To Kwon, the act of “sculpting” a stone with interlocking layers

of time is less a means to an end but a continued signal of what is to come, a

state of constantly reducing and cracking open.

Is

it ever possible to understand the time a stone embodies? An object that seems

like a condensation of eternity? By virtue of the artist, the stone halts its

movement and assumes a form. Shattered fragments allude to its whole, and a

broken line points to a corner it seeks to complete. Black ink bears the abyss

that absorbs all light and color. Nevertheless, the stone, by nature, refuses

to be moored, lessening the pigment’s vibrancy that strove to penetrate even

further or crumbling to even smaller pieces. It reminds us that, as a part of

nature, its clock is yet to stand still.

Installation

view of 《We Go》

(DOOSAN Gallery, 2024) ©DOOSAN Art Center

When

these stone sculptures are introduced to the exhibition space, the definition

of “subject” extends to include those experiencing the sculptures. If

experiencing a painting can be seen as observing a surface and engaging in an

illusion, then experiencing a sculpture is akin to journeying from one surface

to the next and tiling them together to envision a form. Hence, such experience

results in movement, as it requires the subject to physically navigate around

the work.

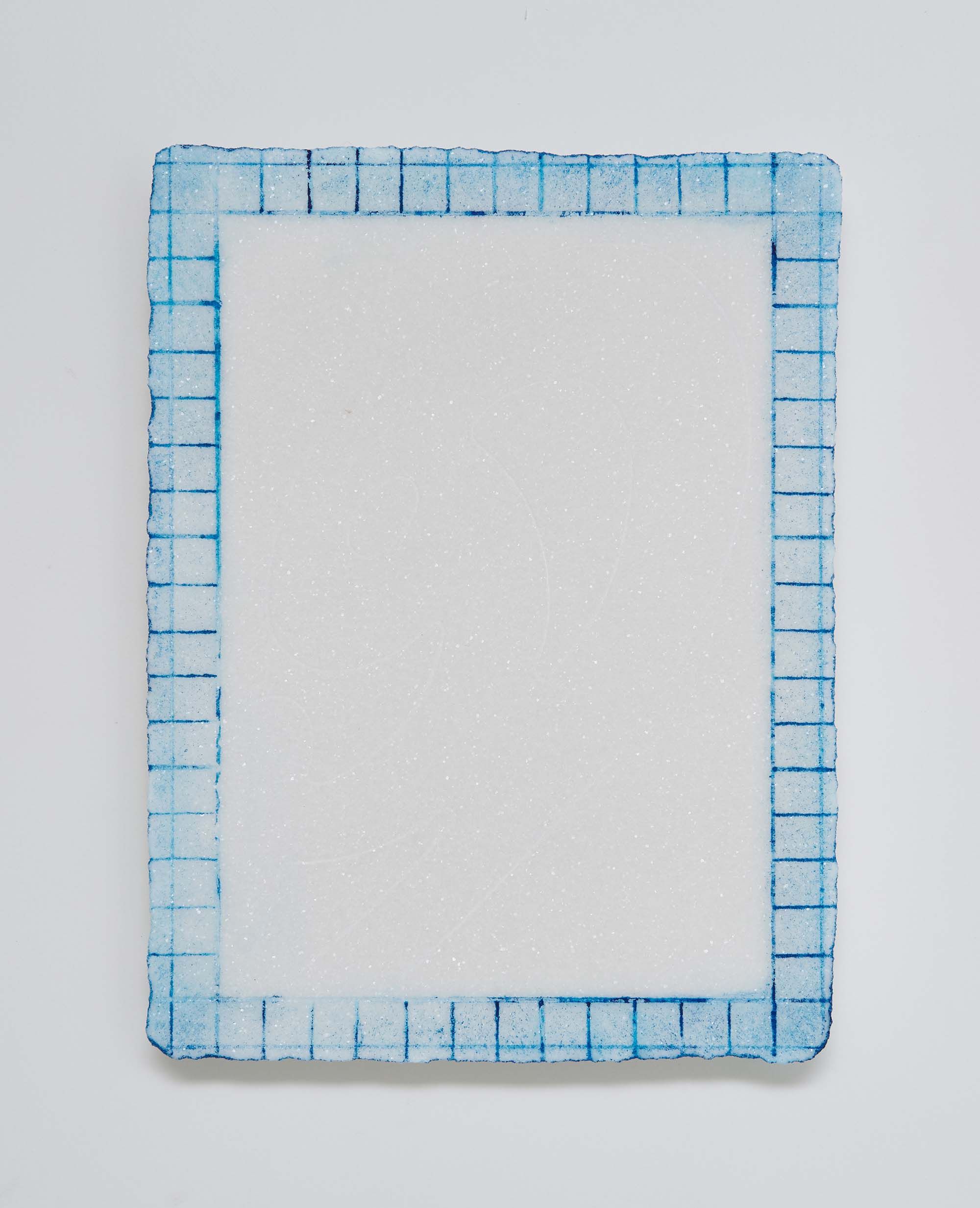

The flat sculptures on the wall might appear to be abstract paintings

on shaped canvases, but their depth is not quite the indicator of what they

are. What is crucial is the fact that they are fragments broken off of a larger

whole. The procession of wall-hanging pieces is, therefore, like a blueprint

that lays out the numerous facets of a whole—the original sculpture or span of

time.

The

task of the viewer is to reassemble these pieces and trace back their previous

forms and times. To stitch these times together, the viewer must stand in the

center of the space and piece the surrounding sculptures into a connected

narrative or step closer to the sculptures and search for hints of an

unfinished story. When the movement of the artist and the movement of the

viewer interact, the “sculptural experience” at that moment, is when scattered

subjects fall into line and separate spacetimes come into contact.