Within

the space where artist Kwon Hyun Bhin works, time seems to stand still.

Sculptural actions that are carried out repeatedly within the constantly

changing flow of nature paradoxically cause time to settle. While meeting the

artist and observing the progression of her work, I found myself thinking more

than usual about the speed and flow of time. In her studio in Paju, which she

shares with her parents—both sculptors—the passage of light and the changing

seasons can be felt fully, with one’s entire body.

Throughout the space, chunks

and fragments of various kinds of stone are scattered about, resting there like

still lifes from a familiar everyday scene. Perhaps for the artist, stone had

long occupied a corner of her mind as a landscape that is “always there, yet

not there,” much like the rice fields and mountains visible through the studio

window. Her relationship with materials (in this case, stone) may have been

formed naturally from the very beginning.

The

materials the artist chooses—either excessively light (such as Styrofoam) or,

conversely, heavy like stone—might at first seem distant from the traces of

water, ice, clouds, wind, or the atmosphere of the sky that she seeks to

explore and reveal. Yet when one quietly observes natural phenomena, this

choice can also feel inevitable. Just as we cannot stop time from flowing, we

cannot fix the shapes and movements of clouds in the sky, nor can we halt the

flow of water. However, invisible moisture in the air can become ice, and

clusters of ice crystals can form clouds—moments in which forms or states come

into being.

Like

time made visible through the sand inside an hourglass, stones that have fallen

from the ground and clouds that have fallen from the sky became the marble

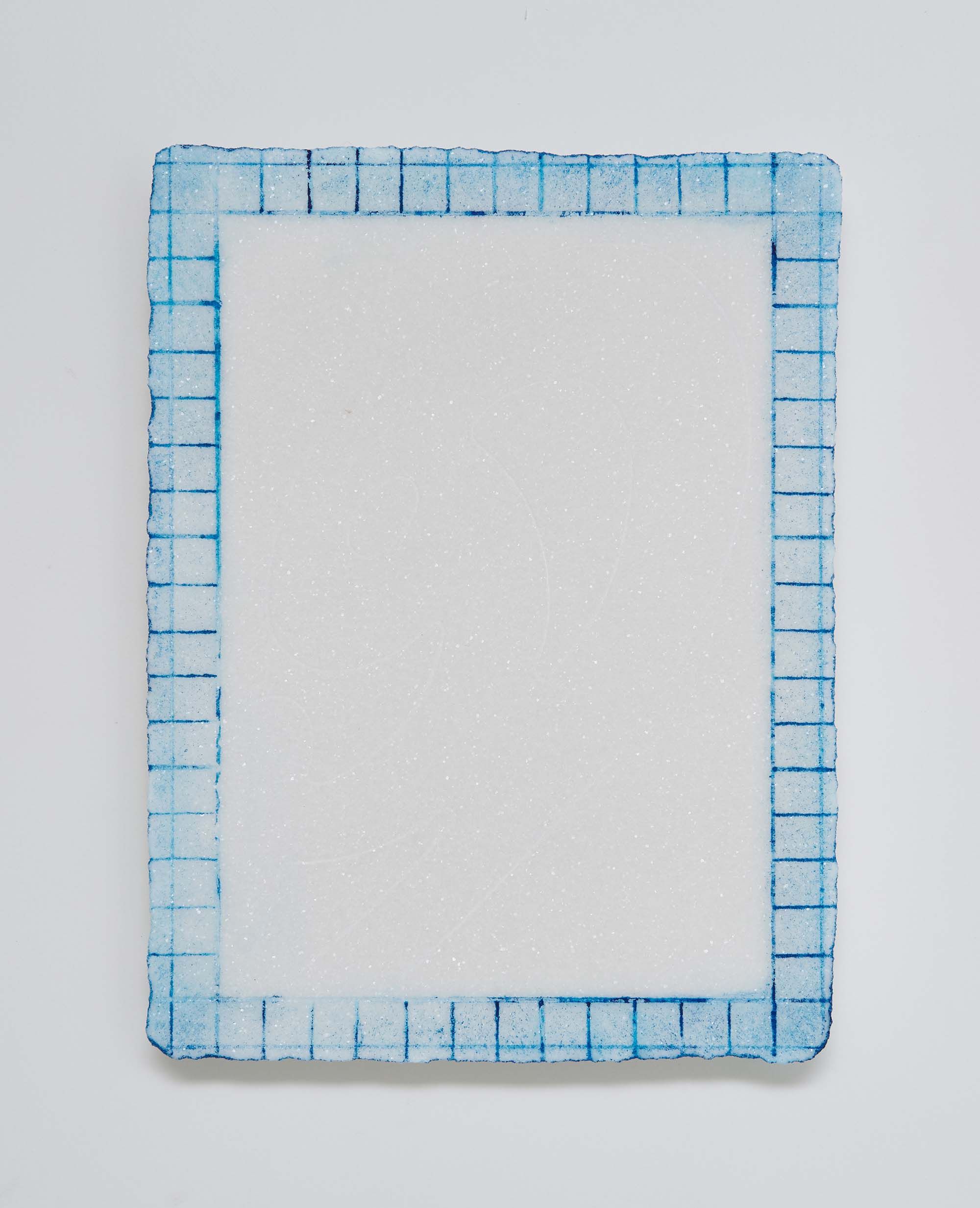

sculpture series ‘Cumulus humilis-fractus’. The phenomenon of water droplets

forming on the outside of a glass filled with ice—appearing as if they have

moved from the inside to the surface—gave rise to the works ‘Ice–Water–Cup and

Air’ (2021) and the ‘Humming Facades’ (2021) series on marble slabs.

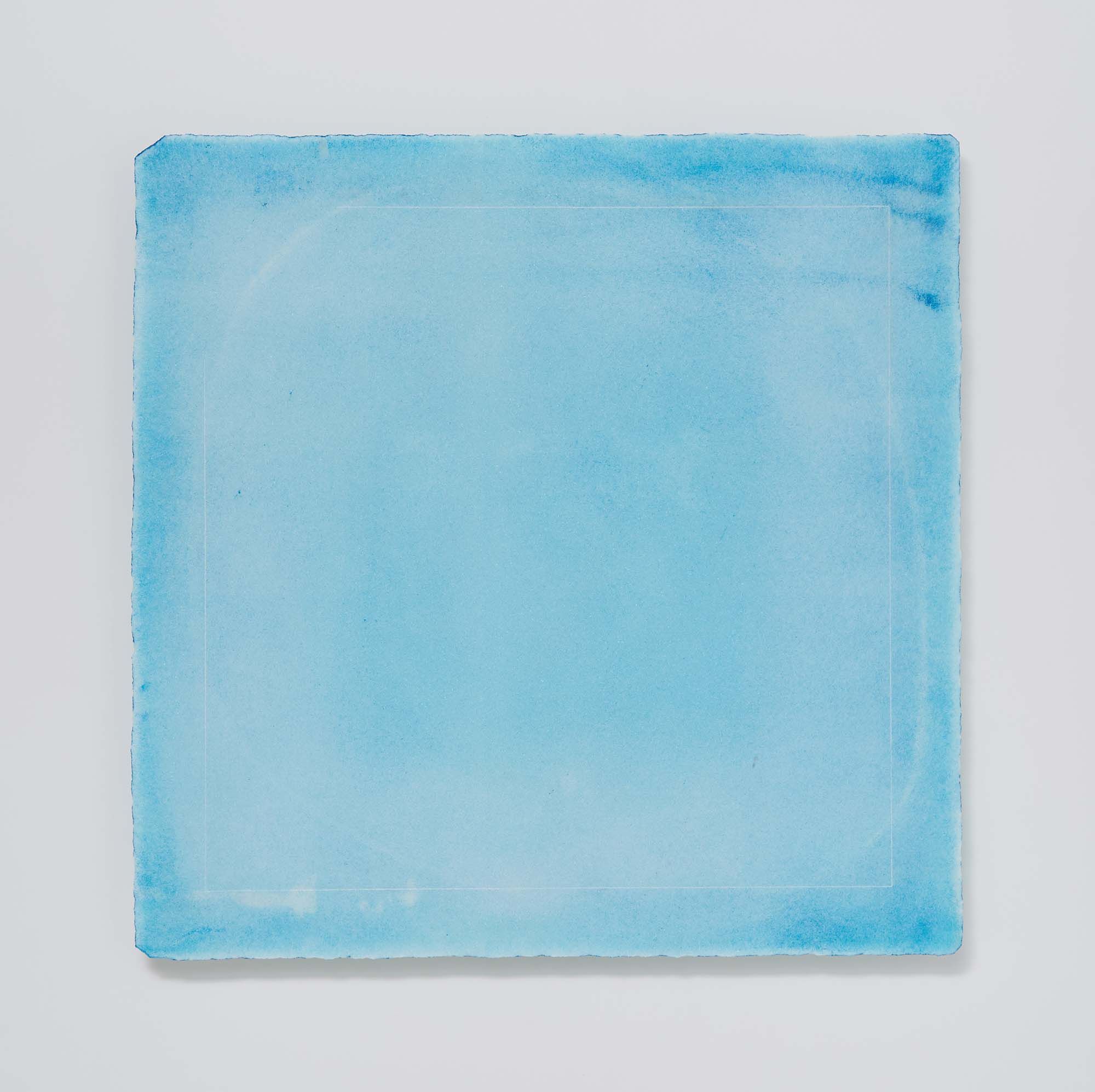

These

series, presented in the exhibition 《HOURGLASS》(2021), trace their origins back

to Water Relief (2019), in which water-based

pigments were applied to white marble so that blue pigment seeped into the

stone as if it were being carved and chiseled. At that stage, rather than

focusing on cloud motifs, the artist seemed more concerned with exploring the

material of white marble itself and considering how to establish a relationship

with it.

By imagining a softened, liquefied form of carving—allowing pigment to

seep in rather than physically splitting the stone with a chisel—we glimpse the

artist’s attitude toward resisting a fixed understanding of material

properties. It also felt as though she was making a reckless yet courageous

declaration of her own in the face of the immense history and weight of stone,

which holds an unfathomably long span of natural time before which humans can

only feel helpless.

To be unable to predict the outcome of a fracture is to

relinquish a degree of control. In an era where tools such as software programs

or 3D printers could allow one to anticipate the final form of a work from the

outset, choosing instead to leave the process wide open to the anxiety of the

unknown feels distinctly unfamiliar today.

The

various choices of stone that Kwon Hyun Bhin has made over time, along with her

drawings that bear the character of rubbings, appear as part of a journey

leading to the ‘Cumulus humilis-fractus’, ‘Ice–Water–Cup and Air’ (2021), and

‘Humming Facades’ (2021) series. In 2019, she spent a period of time creating a

body of work by carving or chiseling marks such as holes and lines into the

surfaces of dark-colored stones like basalt or sandstone, rather than white

marble.

The inherent color, properties, and forms of the raw stone were laid

out broadly, like large-scale drawings responding to the shape of the space,

powerfully expressing themselves as they were. However, unlike the attempt

in Water Relief (2019), which sought to penetrate

and unsettle the materiality of stone itself, the artist’s traces on the

surface in these works remained more reliant on the original form and color of

the stone, resisting fusion like oil and water.

Basalt and sandstone, with

their strong inherent character and coloration, may not have easily allowed

space for intervention, making it difficult to find points of contact. Perhaps

this was a process of seeking modes of dialogue suited to the specific

character of each stone. In contrast, white marble—unlike basalt or sandstone—is

neutral and relatively receptive to external, heterogeneous elements, allowing

the artist’s intervention to proceed more fluidly. This quality is revealed in

the ‘Cumulus humilis-fractus’, ‘Ice–Water–Cup and Air’ (2021), and ‘Humming

Facades’ (2021) series presented in the exhibition 《HOURGLASS》(2021).

The

marble sculptures of the ‘Cumulus humilis-fractus’ series are scattered across

the gallery floor, forming shapes of fragmented clouds as if they had broken

away from a larger mass. These cloud fragments, resting on the ground and no

longer able to dissipate, hold both earth and sky within them. In addition to

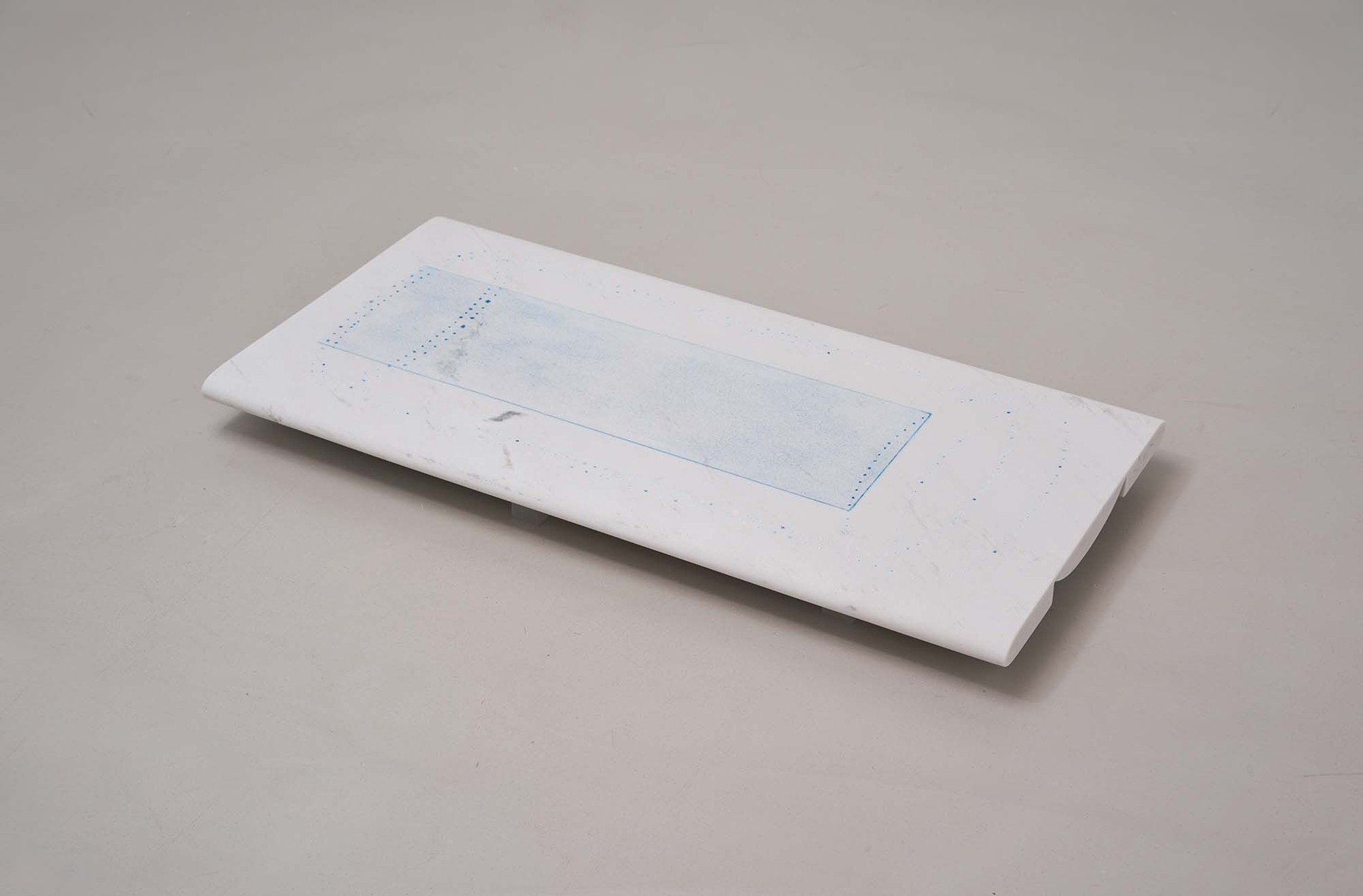

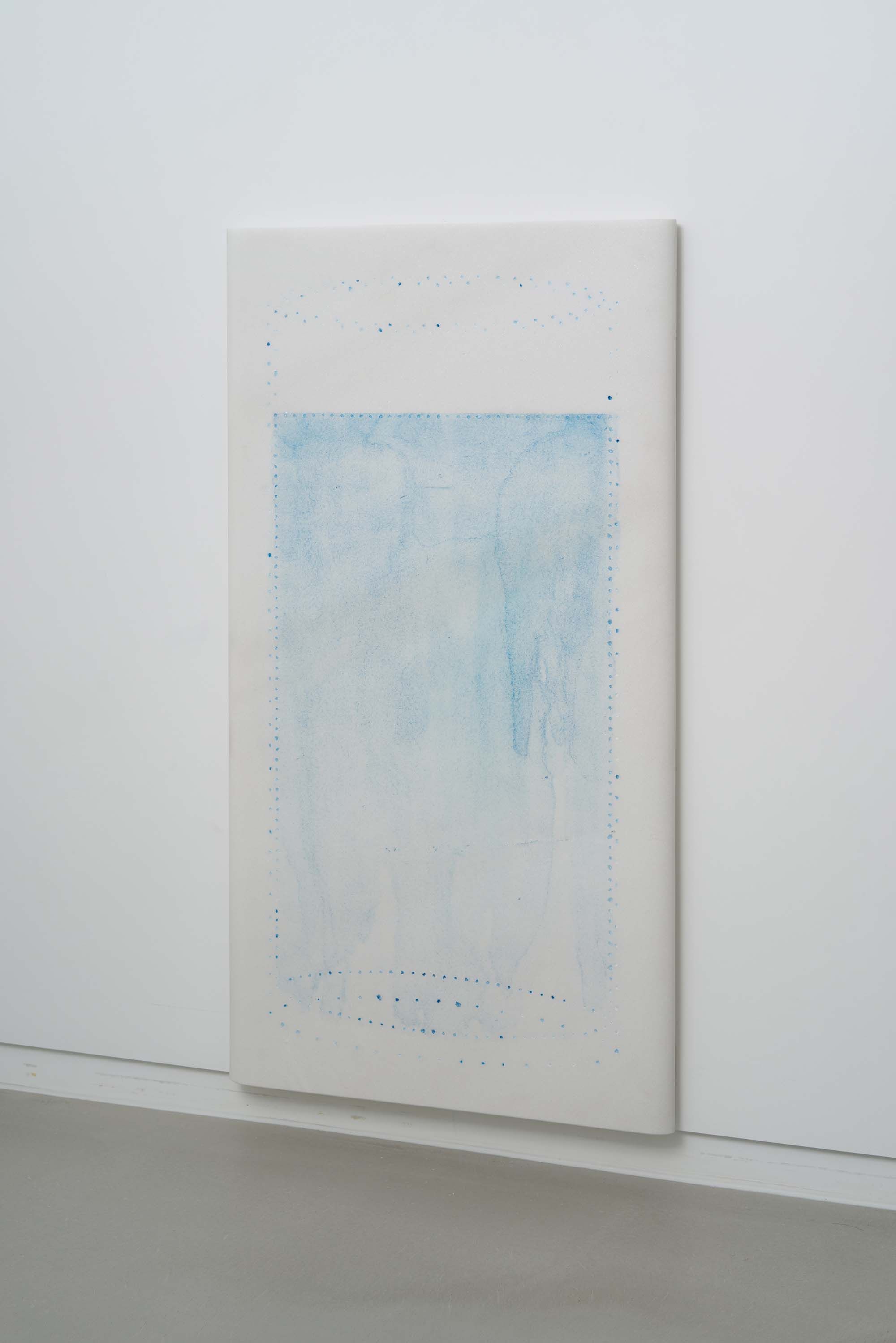

these sculptural clouds on the floor, the ‘Ice–Water–Cup and Air’ (2021) and

‘Humming Facades’ (2021) series, made using flat white marble slabs, may appear

planar in form but nonetheless encompass the space beyond the stone.

Thinking

that the transformation of ice melting into water inside a cup resembles the

way clouds disperse across the sky, the artist repeatedly carved dots, drew

lines, applied color, and erased it on marble slabs (‘Ice–Water–Cup and Air’

(2021) series). The resulting images do not resemble the form of any specific

object; rather, they are traces of contemplation on entities that cannot be

fixed, as well as a method for drawing the materiality of stone closer to

herself.

Although these works use flat marble slabs, they are clearly

three-dimensional objects with six sides—front and back, left and right, top

and bottom. The edges of this cuboid have been softened, while the top and

bottom retain minimal concavity, as if they could hold something. The thin stone

slabs maintain the bare minimum required to be three-dimensional, moving back

and forth across the boundary between plane and volume.

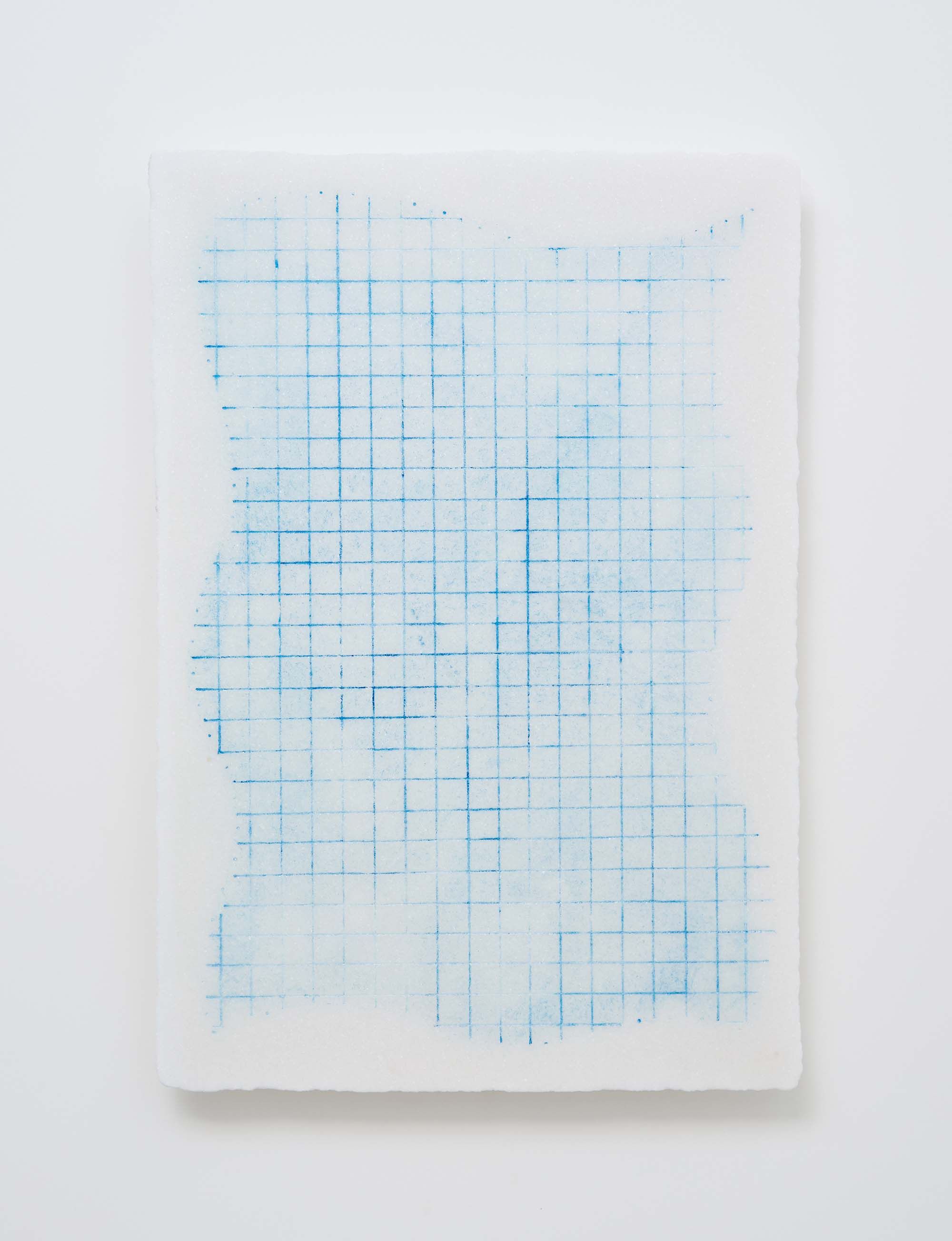

This continues in the

‘Humming Façade’ (2021) series, where the works begin to move away, little by

little, from metaphors of clouds, water, and ice. The surface of the stone is

ground ever thinner, and dots, lines, and color increasingly remain as traces

of the sculptural act itself. The artist’s domain within the stone gradually

expands, and she diligently grinds and grinds again—almost to the point where

the edges might crumble—repeatedly applying and erasing blue ink to further

inscribe her presence.

My

own fragmented flow of time spent thinking overlaps with the artist’s act of

breaking stone, repeating cycles of interruption and continuation. Writing

inevitably comes to resemble the attitude of the maker embedded in its subject.

After long periods of waiting, moments of abstract yet concrete realization

flash in and out, hovering just within reach amid the ambiguous atmosphere the

artist has created. While the artist moves stone, grinds its surface, and

strikes or breaks it to leave marks, external time continues to flow, yet her

time remains suspended. Only when she pauses her body and looks does the flow

of time finally synchronize into one.

Works

that hold nature within them continue to flow even after the artist’s hands

have left them. Because humans are inevitably left helpless within this

infinite continuity of time, confronting stone as a material becomes an act

that is both newly felt and unavoidably reckless. Countless attempts and

imaginings generated while moving toward something unattainable foster hope for

moments that feel as though they might be reached.

The

longer I spend looking at Kwon Hyun Bhin’s works over time, the more I find

myself wanting to observe, as slowly as possible, the subtle push and pull

created through the constant exchange of breath and gaze between the artist and

the stone. I also begin to imagine the works—whether as things being made or

things being viewed—aging and resonating together with us. In the end, perhaps

the artist, the viewer, and the works alike are all spending time somewhere

between creation and disappearance, with those two poles set at either end.