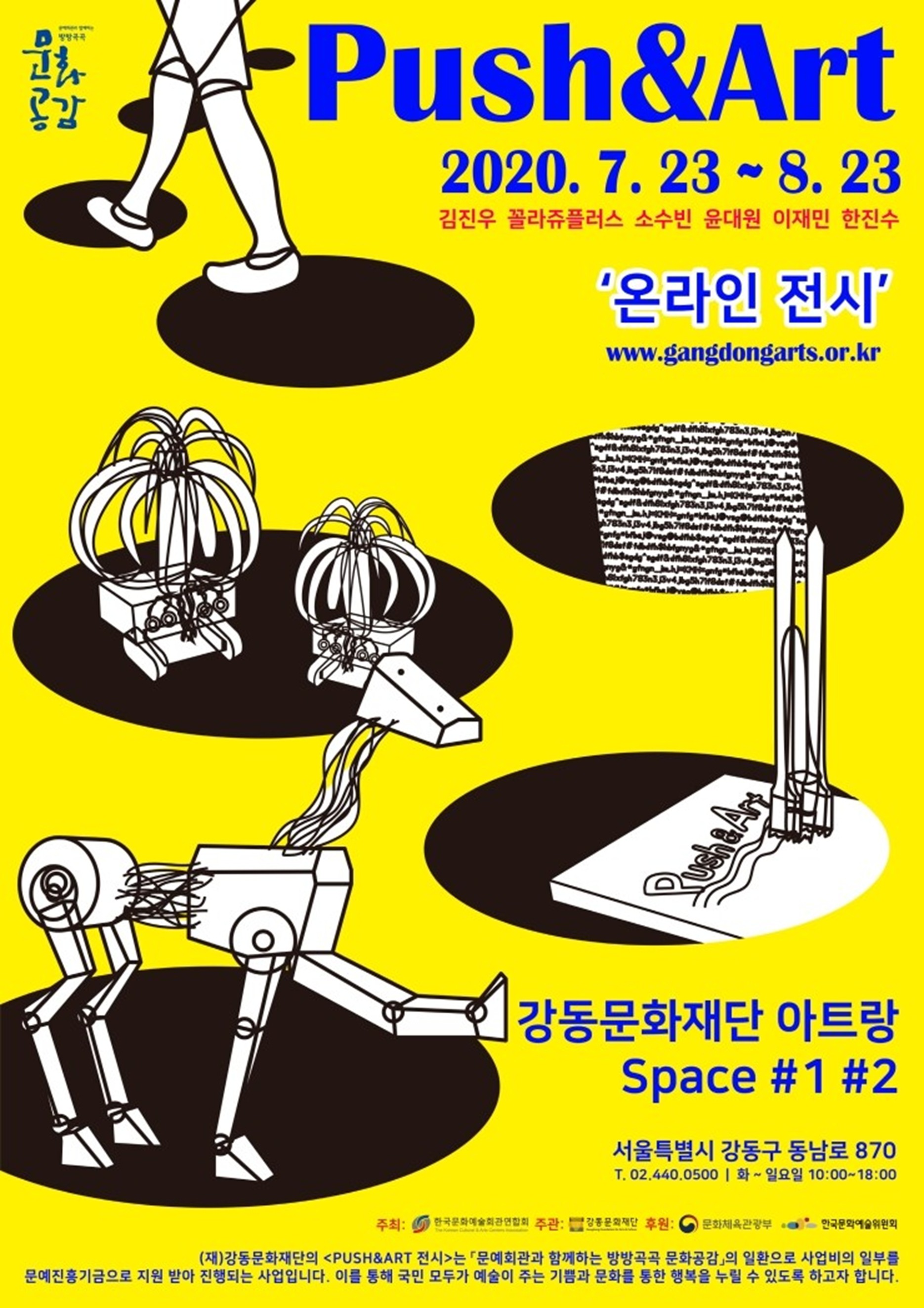

Exhibitions

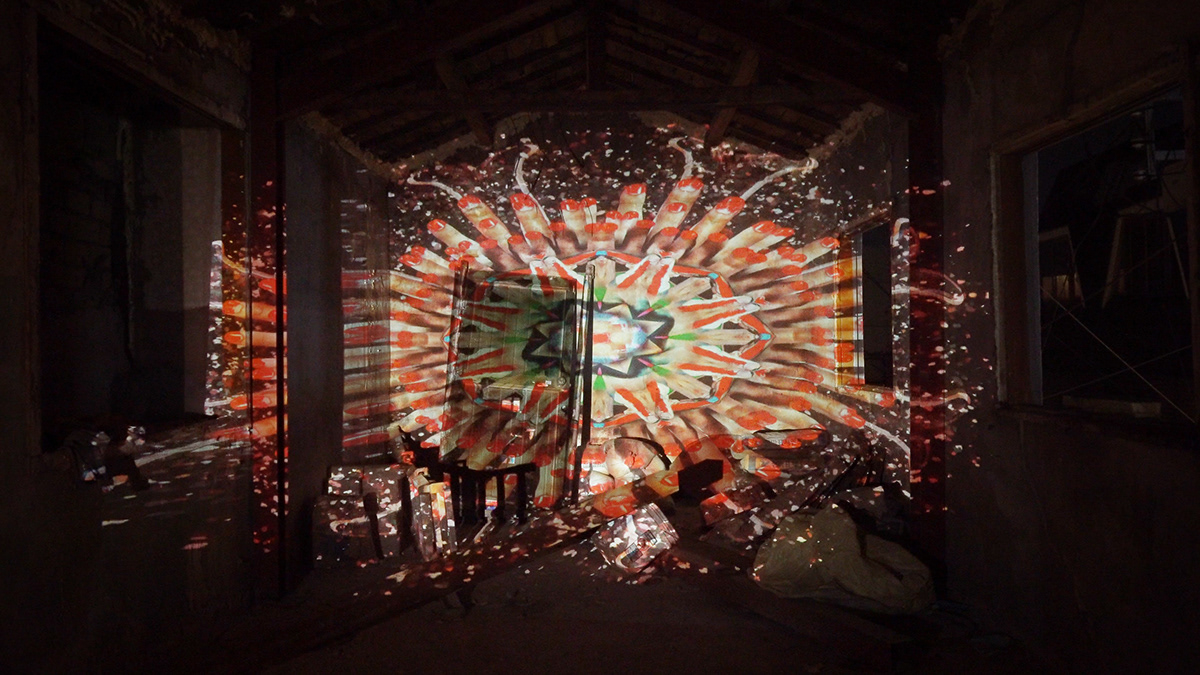

《4 and one-half, knuckle》, 2021.11.18 – 2021.11.29, Art Space Hanchigak, Pyeongtaek

November 17, 2021

Art Space Hanchigak, Pyeongtaek

Installation view of 《4 and one-half, knuckle》 (Art Space Hanchigak, 2021) ©Daewon Yun

Delusions

about the body

1. Two

eyes. Two ears. One nose. One mouth.

Two arms and two legs attached to a single torso, and five fingers and five

toes connected to them.

This is a “body.” With just this small list of words, we can be made to imagine

a “body.”

2. Length

of limbs, shoulder width and waist circumference, head size, hip size, weight n

kg, height n cm.

This is “someone.” Even if the body is the same, through these numerical values

we can imagine a particular person.

A body

whose form is absolute, while size and length are relative.

Only the numbers differ, yet the body always takes the same shape.

At some

point, this began to feel strange and stifling to me. I reconsidered the

seemingly obvious thought: “Perhaps people obsess over relative measurements

precisely because bodies share the same basic form, and decorate or cover their

bodies with something in order to differentiate themselves from others.” But

what if, to begin with, all bodies had different forms? What if form were

relative and size and length were absolute? What if instead of n cm, there were

n limbs, and instead of n kg, n joints?

Installation view of 《4 and one-half, knuckle》 (Art Space Hanchigak, 2021) ©Daewon Yun

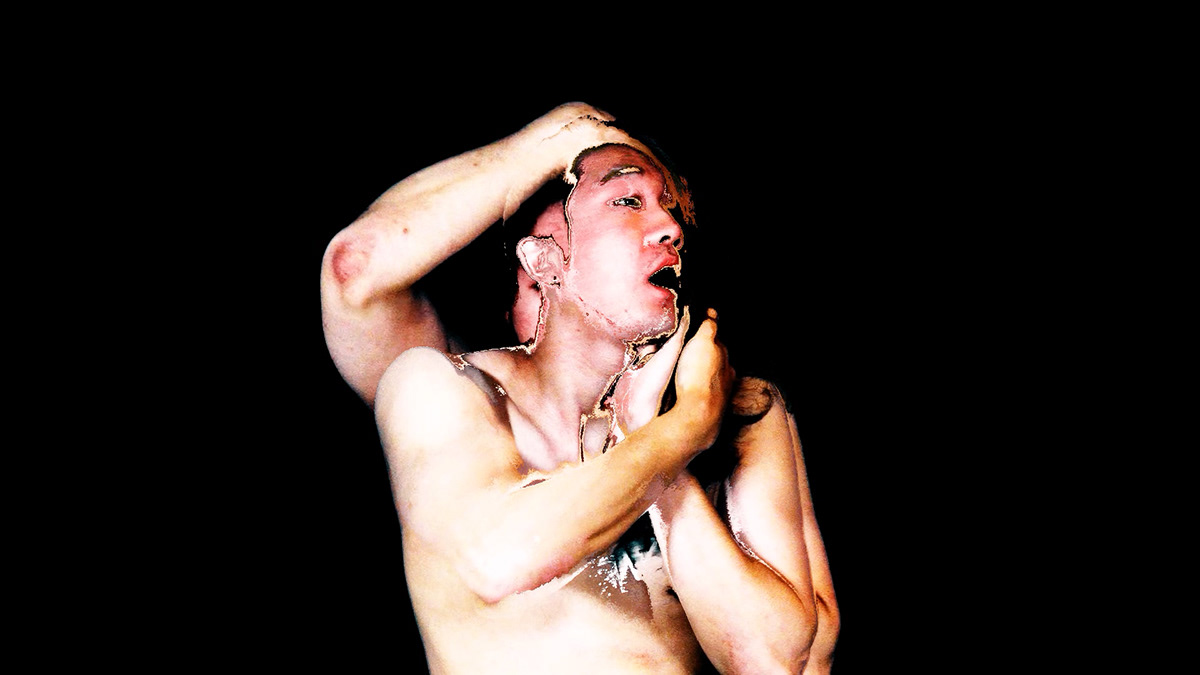

On dance

When I dance, I fall even deeper into these delusions.

If, while dancing in front of a mirror, my body had four arms, five knees, a

neck that could rotate 360 degrees, arms that could extend as much as I wanted,

an upper body that could separate, or joints that could bend in all

directions—what kind of movements would be possible?

In truth, what makes us admire someone else’s dance is that,

despite having the “same body,” they perform movements that we cannot. Even

when the movements are identical, differences in proficiency generate different

auras and evoke emotions that are difficult to put into words. Then what kind

of aura might be produced by the gestures created by the images in my

delusions—that is, by “bodies with different forms”?

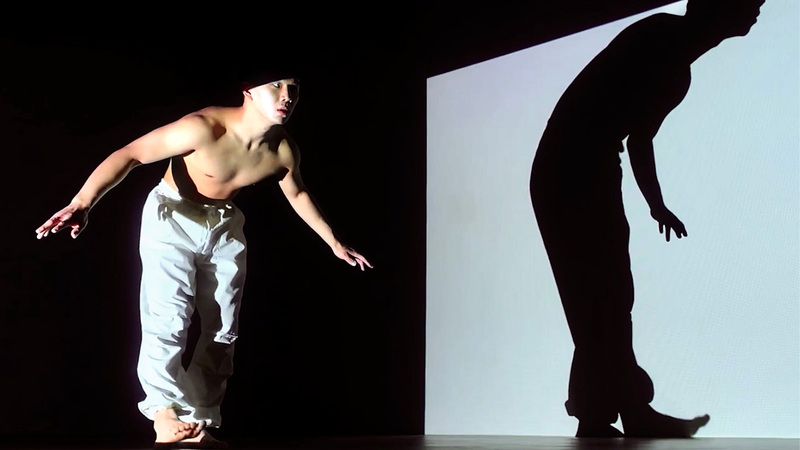

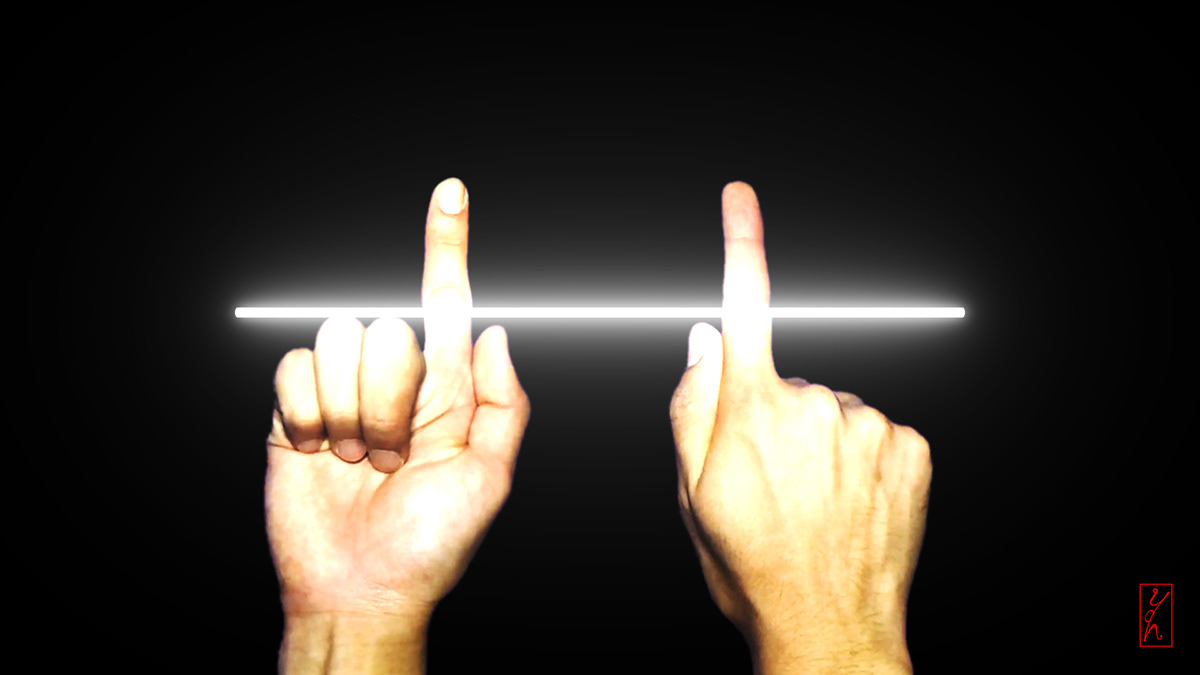

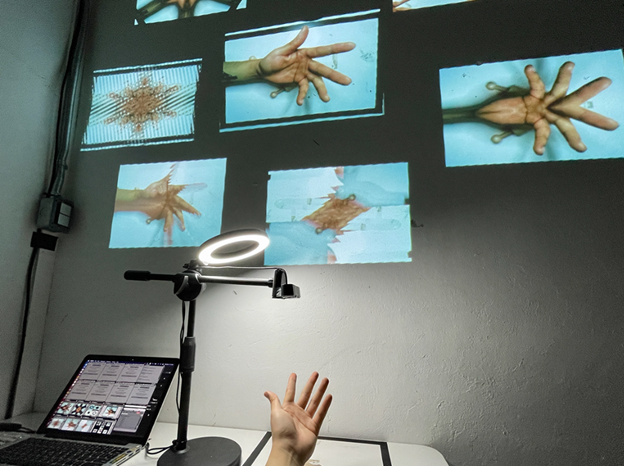

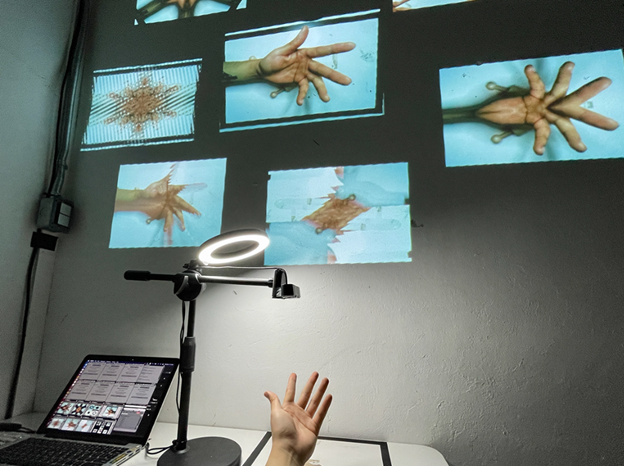

The Dance of the Avatar

Digital media proved to be particularly well suited to unraveling

these concerns. Once my body was converted into digital signals, it could be

edited, dismantled, and recomposed in various ways, allowing it to expand into

a “new form of body.”

I began to dance by fragmenting and reassembling my body

and its gestures. Naturally, my dance was unable to contain the emotions that

arise when moving the body directly. Instead, however, I was able to discover a

strange sense of attraction in places I had never anticipated.

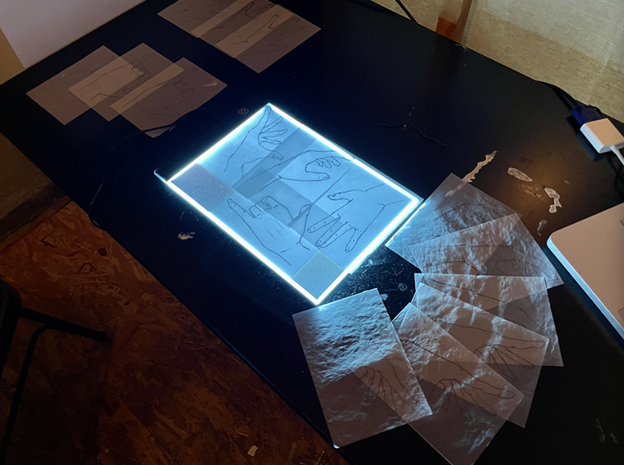

Installation view of 《4 and one-half, knuckle》 (Art Space Hanchigak, 2021) ©Daewon Yun

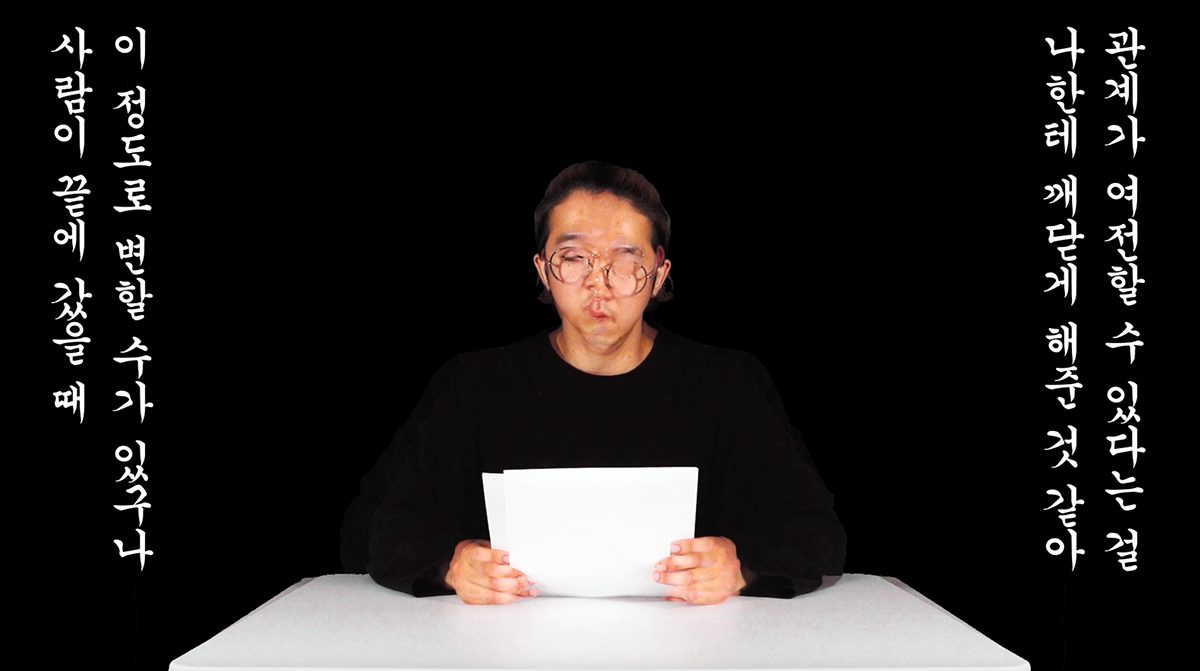

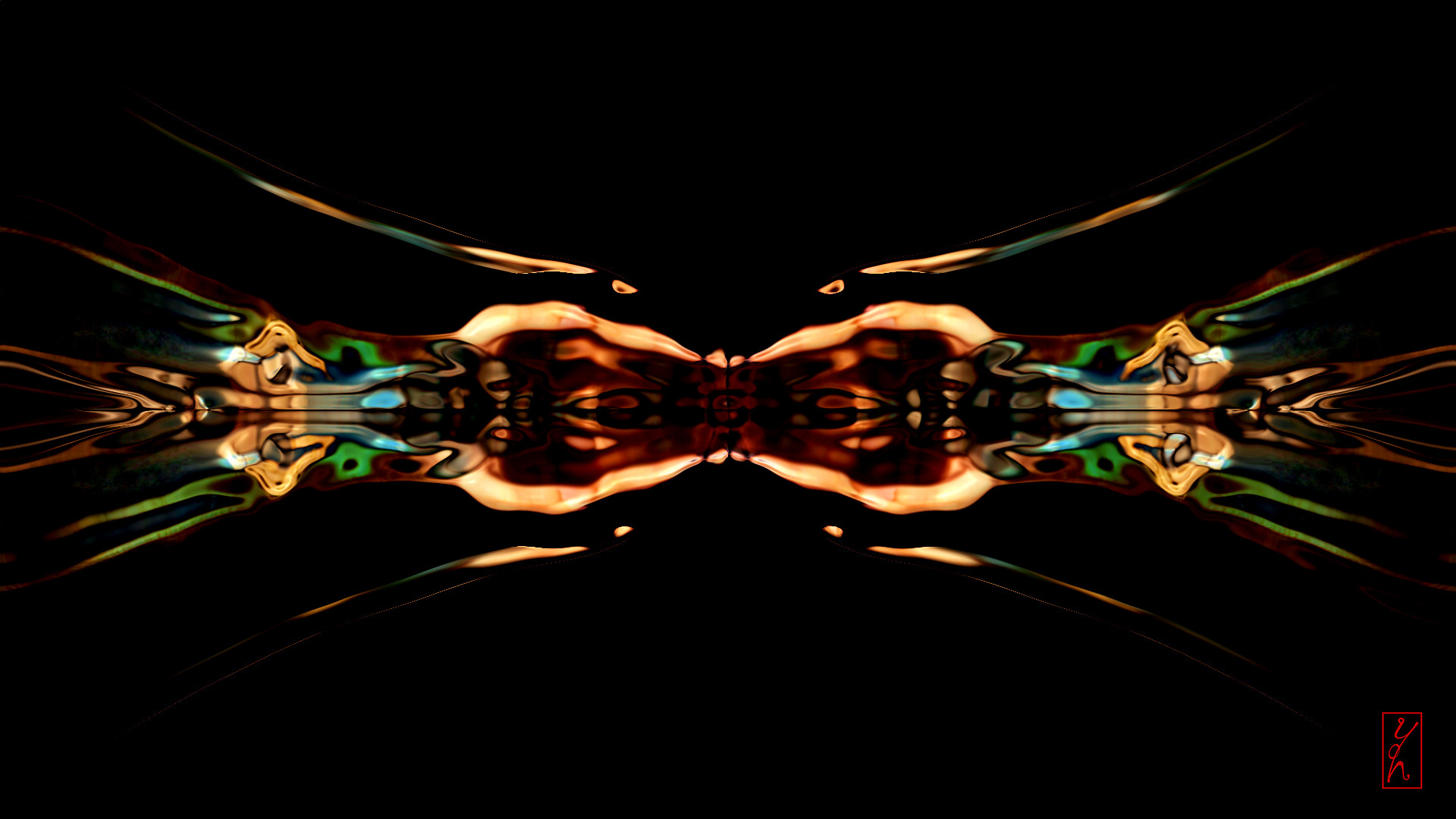

Searching for the grotesque

All of my dances contained an element of the “grotesque.” Perhaps

this, like the aura produced by conventional dance, arises precisely because

bodies share the same form.

It is a quality that naturally emerges when the familiar form of the body—so

familiar that we no longer even recognize it as familiar—is rendered

unfamiliar.

Contrary to my expectations, however, the source of the grotesque

was not the form of the body, but the “edited gesture.” Could it be that this,

created by fantastical movements freed from the laws of physics, constitutes

another aura that my dance can possess?

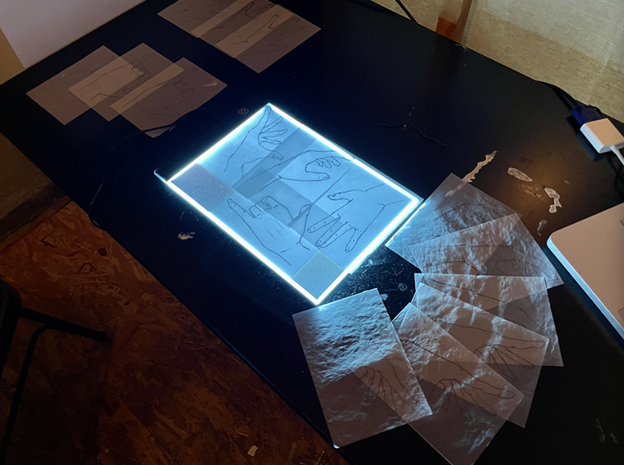

I began a strange research project to find this “grotesqueness.” I

established my own rules, edited gestures in various ways according to certain

criteria, and documented the process.

Through this process, I discovered that when movements are “perfectly”

symmetrical, “perfectly” aligned, “perfectly” identical and endlessly repeated,

or move at a “perfectly” identical speed, my dance becomes increasingly

grotesque. From this, I derived a new keyword: “perfection.” Gestures placed

upon numerically calculated coordinates revealed a balance between the perfect

and the imperfect.

Perhaps the reason I am conducting this strange research is to

search for a hidden number—like four and one-half—within the collision between

the digital (machine), which outputs perfect values of 0 and 1, and bodily

gestures, which can never be perfect and therefore evoke emotion.