1. Faith

When

I was young, religious activity felt like an assignment I didn’t want to do. At

certain times, I had to give up things I enjoyed and remain in a specific place

for long hours, where I was required—regardless of my actual state—to maintain

a devout heart and a sacred attitude. Perhaps because of this, I grew

suspicious of every rule and regulation associated with religion. I disliked

God, and I resented Him.

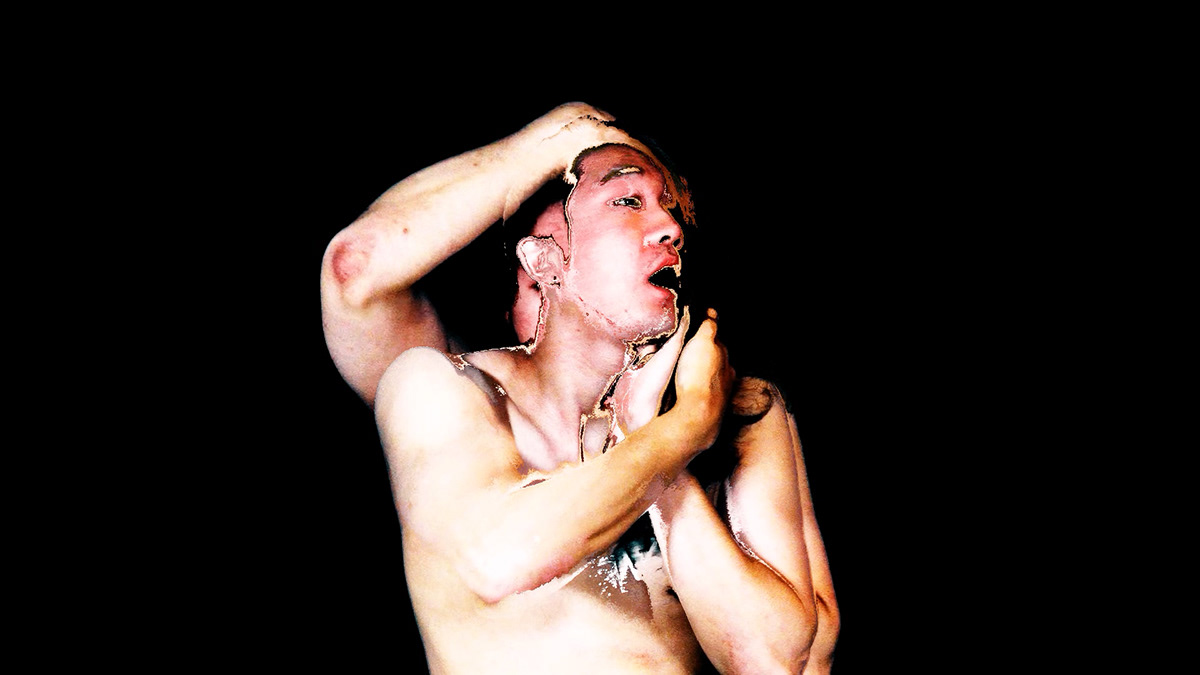

Then

one day, I found myself in a critical situation, and not long after, it was

resolved safely. In truth, it was nothing more than a small incident that

unfolded over a rather short period of time. Yet the reason I still remember it

is because, at the moment it was resolved, I found myself crying out from deep

within my heart, “Lord, thank you.” After that, I stopped all religious

activity.

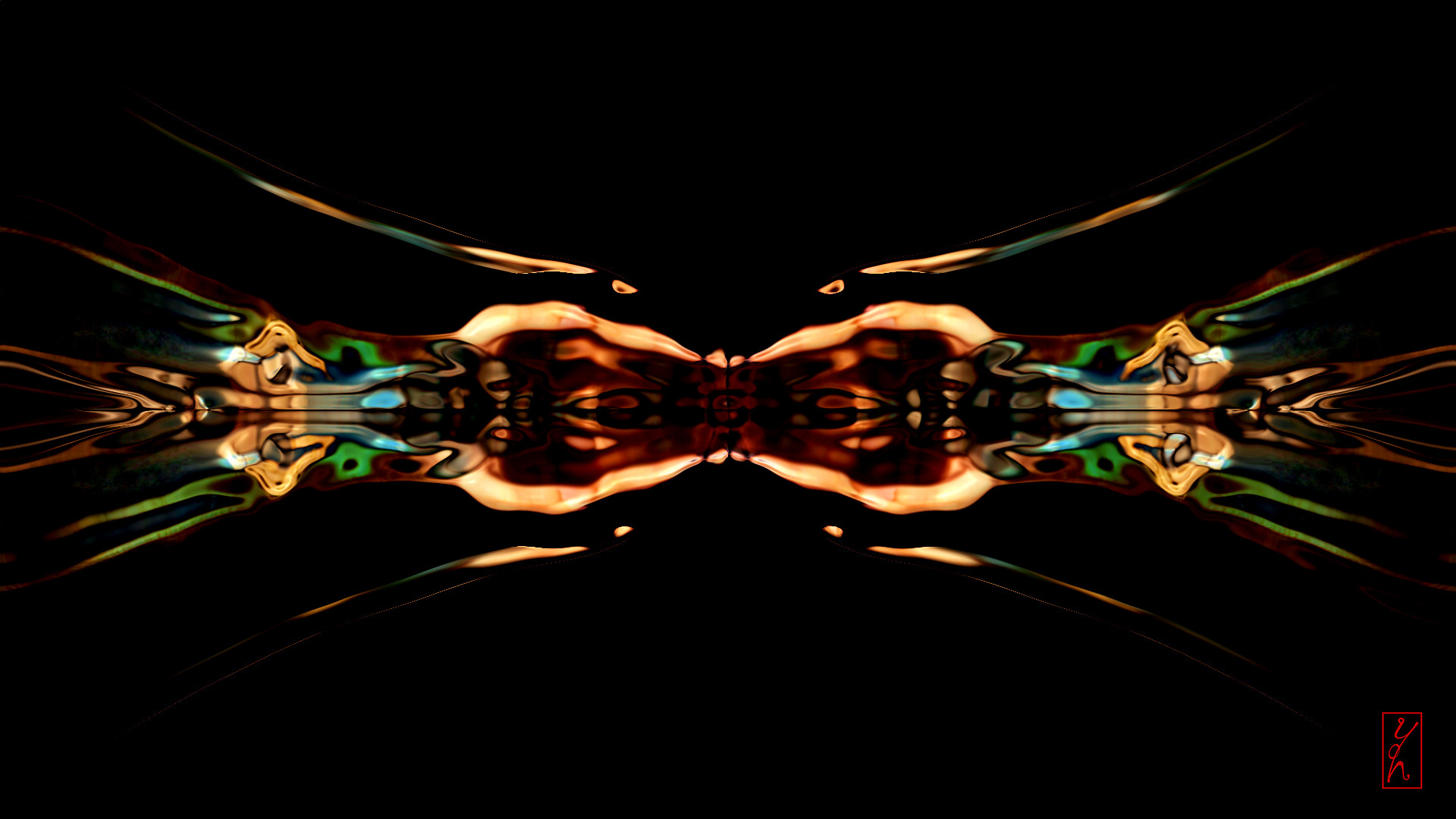

2. Doubt

What

is an absolute being? What is the world to Him—and what am I? How can one trust

Him? Where does faith in Him begin? Fundamental questions about faith continued

to circle endlessly through the relationships, events, and environments I

encountered as I lived, branching out in multiple directions and shaping my

thinking. I came to believe that individual subjectivity, justice, convictions,

and values are all based on “belief,” and thus, when trying to understand

someone, I habitually examined what they believed, why they came to believe it,

and how strongly they held that belief—tracing the origins of their faith.

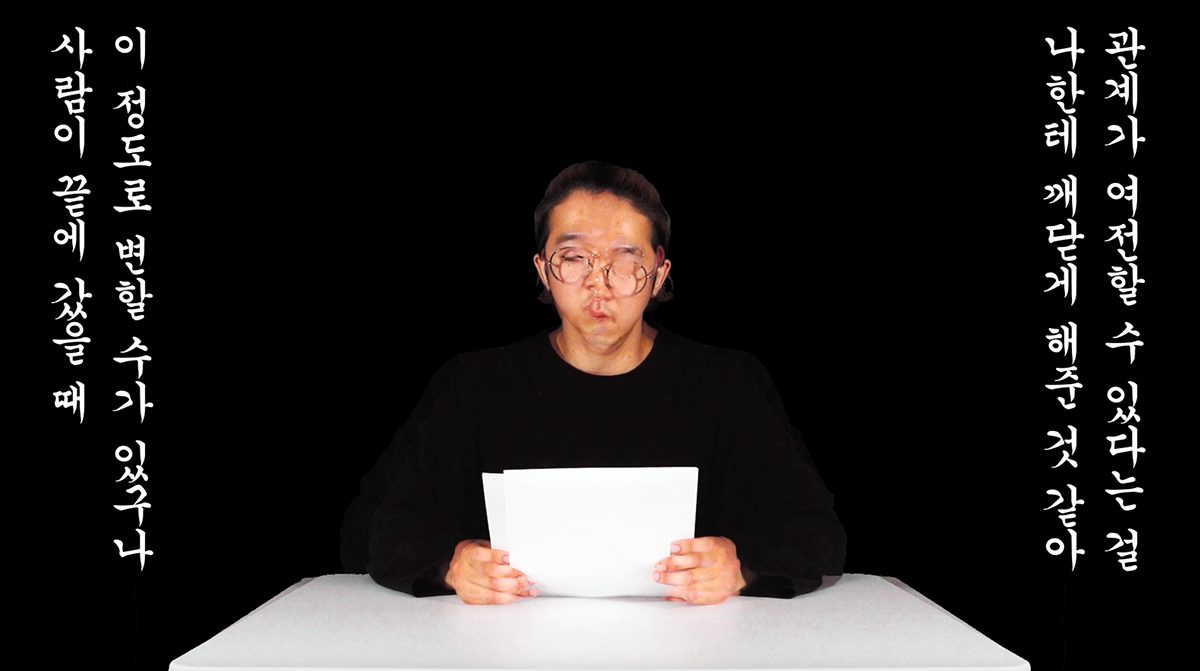

What

troubled me, however, was the question: “What do I believe?” I always

doubted the things I believed in. Doubt might have led me toward better

directions, but unfortunately, I was too busy negating everything. My aversion

to belief only dragged me into a swamp where I could not understand myself.

Consumed by depression and skepticism, I eventually sought out a professional

and began counseling. After several months, what I realized was that an unknown

anger and frustration toward things I could neither doubt nor control had

surrounded me for a long time. And the specific objects of that anger were

“God” and “my father.”

3. Question

I

stopped going to the professional. He intended to dig into my feelings toward

my father, and I wanted to avoid that. Instead, I began chasing “God” once

again. This was not an interest in religion. I simply wanted to know why belief

never formed within me, and why others believed in God. I thought this might be

a way to resolve my anger.

For

that reason, the object of my pursuit was limited to the monotheistic God and

the Bible that were directly tied to my childhood experiences. I did not think

it necessary to visit many different Catholic churches, since Catholicism is

centrally organized, sharing the same doctrine and form wherever one goes.

Instead, I more frequently visited nearby churches and Christians. I moved

among various denominations, asking them why belief was necessary, why they

believed, and how faith in God had taken root within them.

Most

pastors and priests preached their doctrines and convictions, which, as

expected, filled me with discomfort. Of course, they must have been even more

uncomfortable, as I persistently dissected the reasons I could not believe in

an absolute being and the points that inevitably made me angry.

My anger-driven

questions often touched not only on personal belief and biblical content, but

also on the structural problems of religious institutions themselves: Isn’t

belief being used as a pretext for business among people chasing unreachable

hope? If belief changes depending on individual will, isn’t that being not

truly absolute, but merely something you choose to call absolute? If

interpretations change with the times, can such texts truly be scriptures that

contain truth?

Looking

back, I realize that I was simply firing my anger at them. Yet my heart was

more desperate than anyone’s. I wanted to be liberated from anger. I wanted

someone—anyone—to persuade me and grant me belief.

About

half a year into this process, exhausted by repeated confrontations and their

outcomes, something intriguing happened when I followed a stranger—let’s call

him X—I met on the street. Unlike the pastors and priests I had encountered, X

empathized with my questions and began offering clear, logical answers grounded

in the Bible. He was confident that belief in a particular religion begins with

scripture, and that once one realizes its contents are “facts” rather than

“fantasy,” faith will naturally form. He then carefully explained how to read

the Bible.

I

was captivated by X’s explanations, and the doubts I held began to fall into

place one by one. Before long, I followed him to his church.

The

people I met at X’s church gave me numerous answers, and through their

individual stories, I learned how belief had taken root within them. Each of

them carried their own experiences with God and an earnest desperation toward

faith. Yet even as time passed, unresolved questions remained, and I once again

grew dissatisfied with the particular rules they proposed.

Even

there, I was someone who conspicuously resisted belief. I complained to those

teaching doctrine and openly expressed my anger toward God. To them, my

behavior seemed like mere petulance—something that would pass once I had

“learned enough,” “known enough,” or “realized enough.” So I focused even more

intensely on doctrine. I studied it daily, spending several months immersed in

it. When I had grasped its contents and structure to a certain extent, I

concluded that there was nothing more I could gain there. My problem was no

longer one of knowledge. Knowing about an absolute being and believing in one

were entirely different things.

4. Answer

After

tasting defeat once again, the final place I turned to—after going in

circles—was a Catholic church. Catholicism regarded the doctrine I had studied

as among the most dangerous ideologies. Yes—the stranger X I had encountered

earlier was a follower of a well-known cult. When I revealed my experiences to

the priest, the moment the name of that religion was mentioned, his gaze became

a mixture of disgust, anger, and concern.

I

was half-dragged into classes designed to dismantle the knowledge I had

acquired in the cult. Several people who had gone through similar experiences

attended these classes with me. One of them, Y, had been a teacher of that

cult’s doctrine. This puzzled me. To teach doctrine, one would have had to

study there for at least a year and be a high-ranking believer with strong

faith—someone with little reason to leave unless something extraordinary had

occurred. Most of them seemed happy under a firm belief.

I

asked Y whether he had been happy there. He answered that despite the

repetitive routine of prayers from dawn until late at night and surviving on

meals bought with a single thousand won, he had indeed been happy. This only

deepened my confusion. Then why, I asked, was he here now, taking these

classes? Y replied that the stability provided by belief—and the happiness

built upon it—was like a drug.

After

that, I participated in a camp organized by the church. For several days, I

ate, slept, and prayed alongside Catholics, following their ways. I simply went

along with the flow—studying God’s history, reciting the Bible, singing hymns,

sharing thoughts, and performing rituals. Doubt remained, but my emotions were

different from before. There was nothing new, nothing I desired, nothing that

angered me anymore. I felt slightly happy, slightly sad, and slightly blank.

Even

now, I was still struggling between distrust and denial of the absolute being,

and the desire to rely on and lean into Him—still haunted by the shock of that

childhood moment when I cried out, “Lord, thank you.” In the end, what I had

truly sought was not the root of my anger or genuine knowledge of God’s

existence, but simply a way to stop negating and doubting myself. Everything I

had gone through happened because I believed that faith would bring

me stability.

That

is to say, this entire sequence of events began not from doubt, but from

belief. And the emotions that tormented me so deeply were born not from doubt,

but from belief.

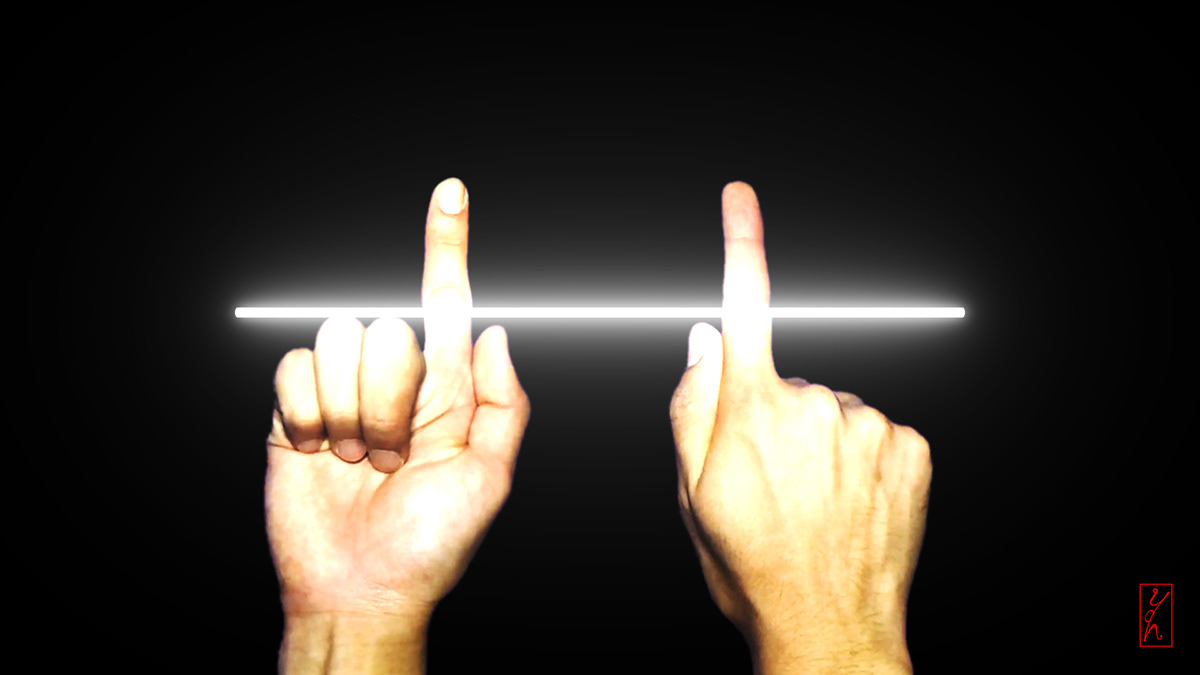

5. 현재

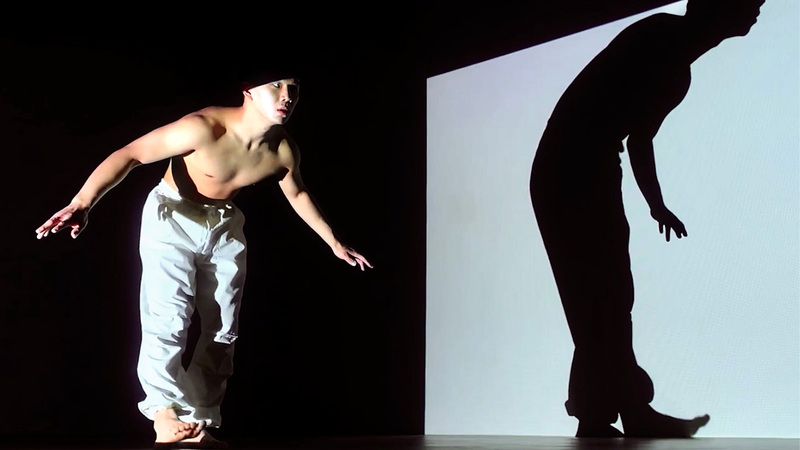

I

continue to doubt, continue to pursue belief, and continue to ask, “What is it

that I believe?” Some believe in hope, some in fate, some in justice, some in

freedom, some in dreams, some in numbers, some in relationships, some in

sensation, some in memory. Belief sustains individual lives, forms collective

cultures, and constructs the systems of the world. We live within belief, and

we need it. When belief is absent, we search for something to believe in, or we

create something we want to believe in.

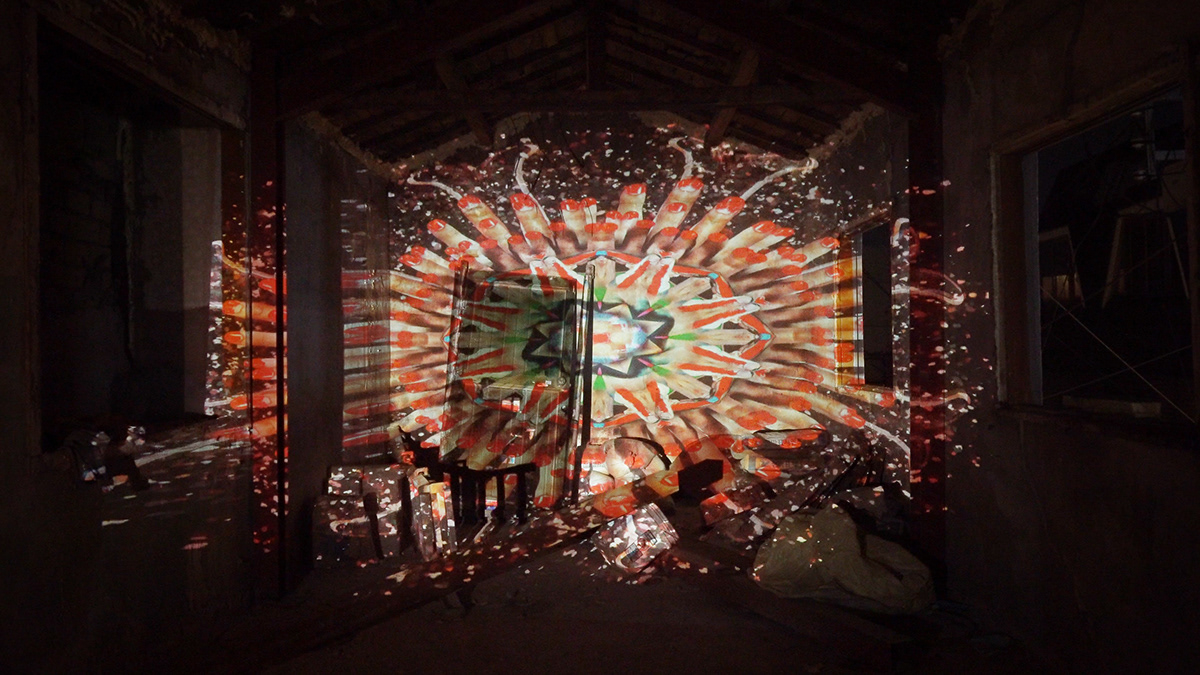

For

this reason, I continue to observe what it is that we believe in and rely upon

today—in other words, what this world worships, praises, and idolizes. This may

be my way of understanding myself and the world, a method and an attitude that

will persist until I stop doubting.