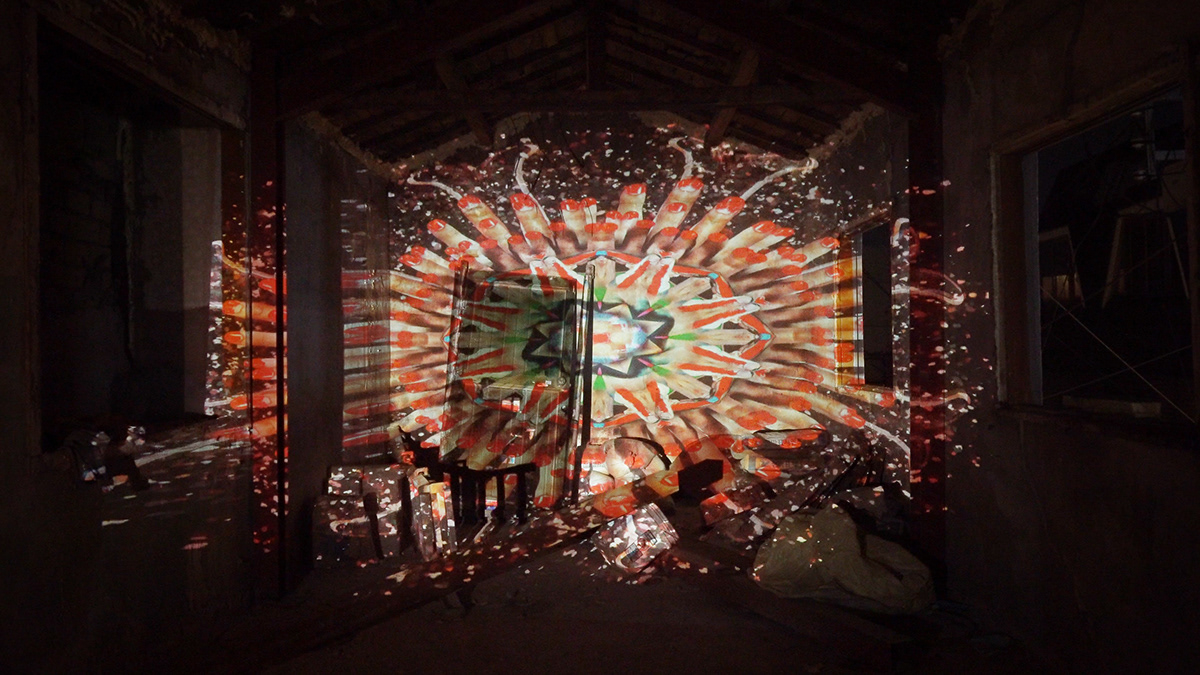

0. Preparatory Movement

Welcome

(歡迎) to this place. Please take a seat on the

chair at the center, or begin by exploring your surroundings. Do you see the

light in all four directions? The structures illuminate the space like

lighthouses. Let us set aside any tension and begin to move slowly. Along with

the rotating mechanical sound, shadows appear, and forms are projected onto

bodies. Those forms may be you—or they may not. Welcome to the apparition (幻影).

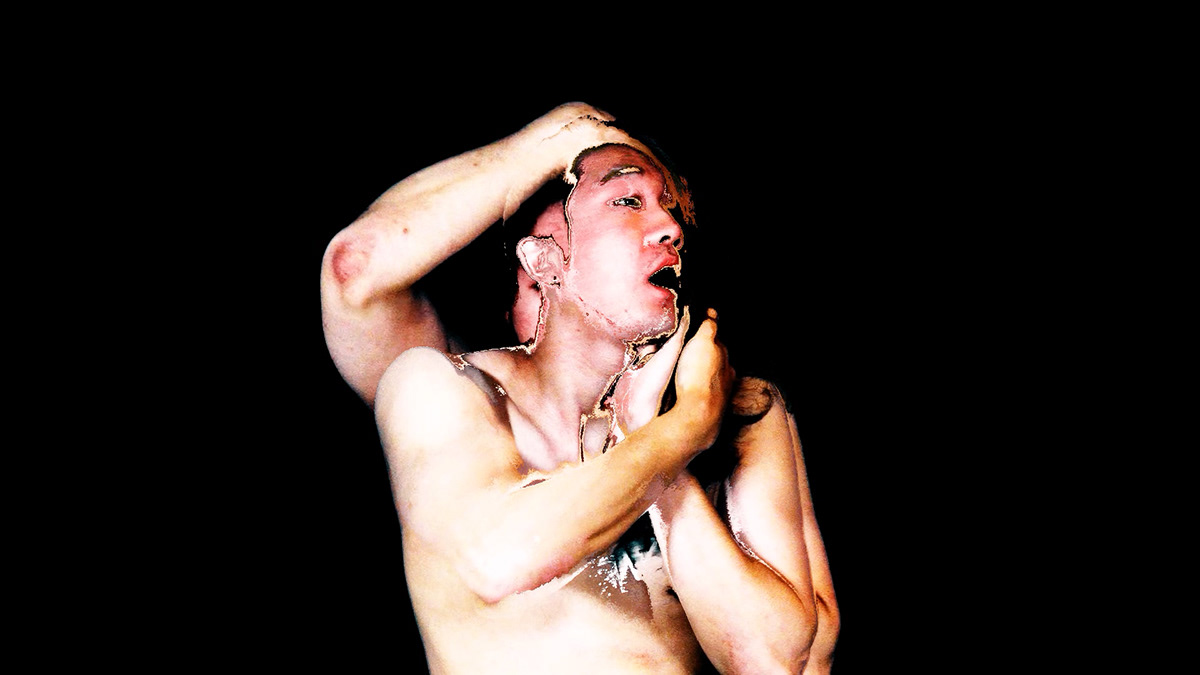

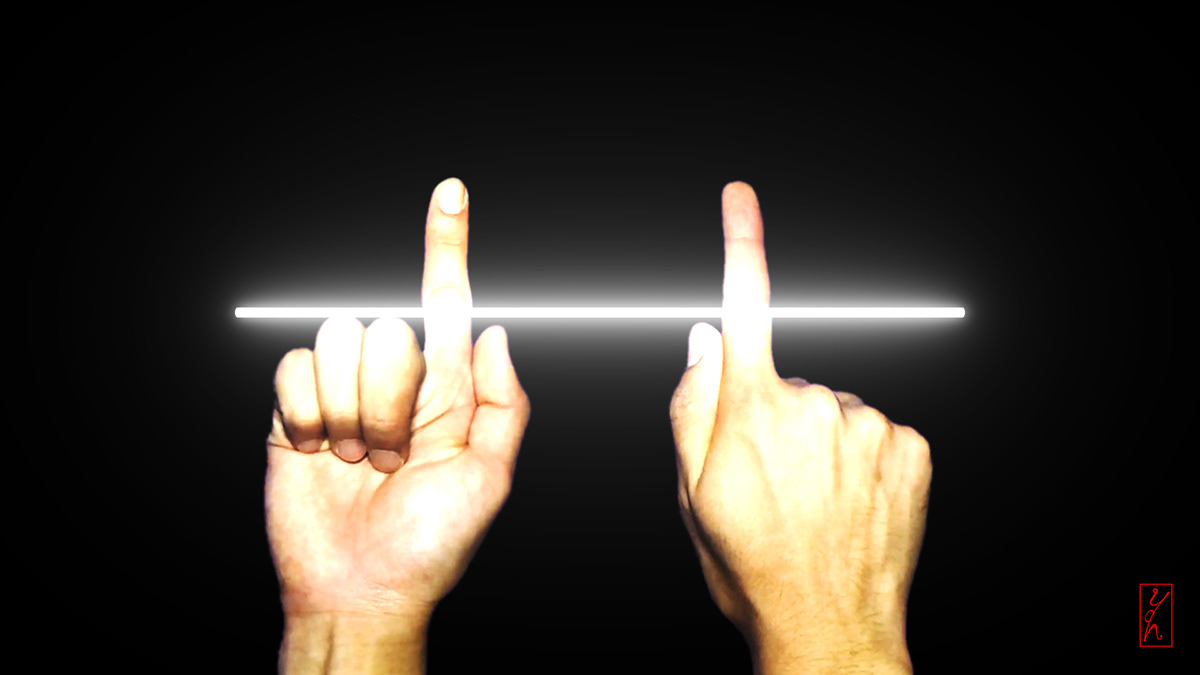

1. 접속 위에 놓인

접촉들

The

performers enter while exploring the space. Without clearly defined gestures,

they appear in their own rhythms, gazing at one another or drifting apart, at

times measuring their distance from the audience. At first, the gaze touches

the body and then withdraws; soon fingertips brush past and slip away. As

bodies draw closer and move apart, the space itself transforms. Here,

relationships are unexpectedly formed and dispersed. These relationships may

exist between body and body, or between body and apparition.

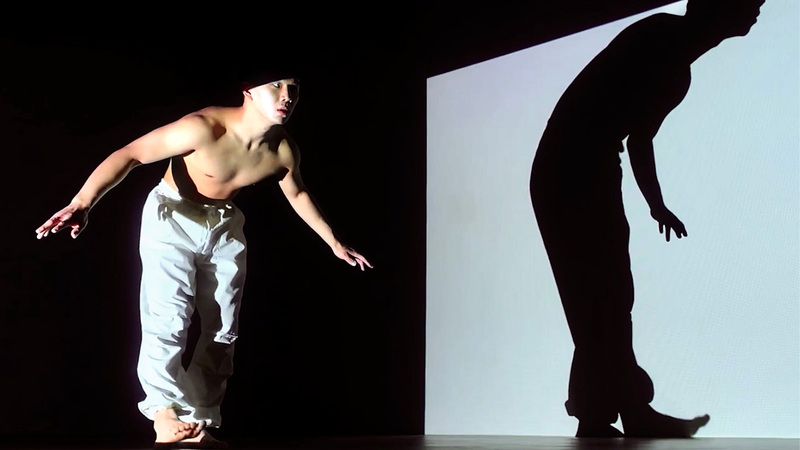

Individual

contacts become ways of perceiving and sensing the “other” through friction

between bodies, gazes, gestures, and distances. Meanwhile, the light/images

emitted from the projector are distorted through slowed speeds and overlapping

frames, projecting “already-past gestures” onto bodies and generating another

time-space.

Images projected onto the body intersect with and deviate from both

past actions and movements occurring in the present. Just as misaligned contact

functions as a sensory point where one crosses into another’s time, the

situation of body/image intersecting with a delayed environment allows the body

of the here-and-now to connect with a body dancing in a different time.

Such

disturbances of perception are not merely visual confusion, but operations of

contact and connection that newly activate the viewer’s own construction of

reality. Performers and audience form relationships while suspending contact

and connection, slowly exploring how sensations of wandering through space

become delayed.

2. Connection without Contact, Bonds through

Misalignment

The

performance then borrows the forms of traditional games—ganggangsullae and

tag—to form collective solidarity through rhythms and misalignments generated

by group movement. With movements and choreography that are not perfectly

synchronized, the performers maintain different speeds and intervals. Centered

around the tagger (performer), the paths gradually tighten into spirals, and

the audience responds with quickened steps to the performers’ gestures and

bodily cues.

Although

collective rhythm is never perfectly aligned, individual differences do not

hinder connection; rather, they become the very conditions through which

togetherness is formed. Speed, interval, and direction shift from moment to

moment. While walking and running together, disparate beats coexist.

Unsynchronized rhythms function not as imperfections, but as modes that reveal

solidarity and contact through being-with.

Furthermore,

even as the audience participates, they sense connections forming and

dissolving, accepting states of deviation or misalignment within rhythm as they

are. Ultimately, communal rhythm emerges not through perfect synchronization,

but through a sensory condition in which mutual misalignments become connected.

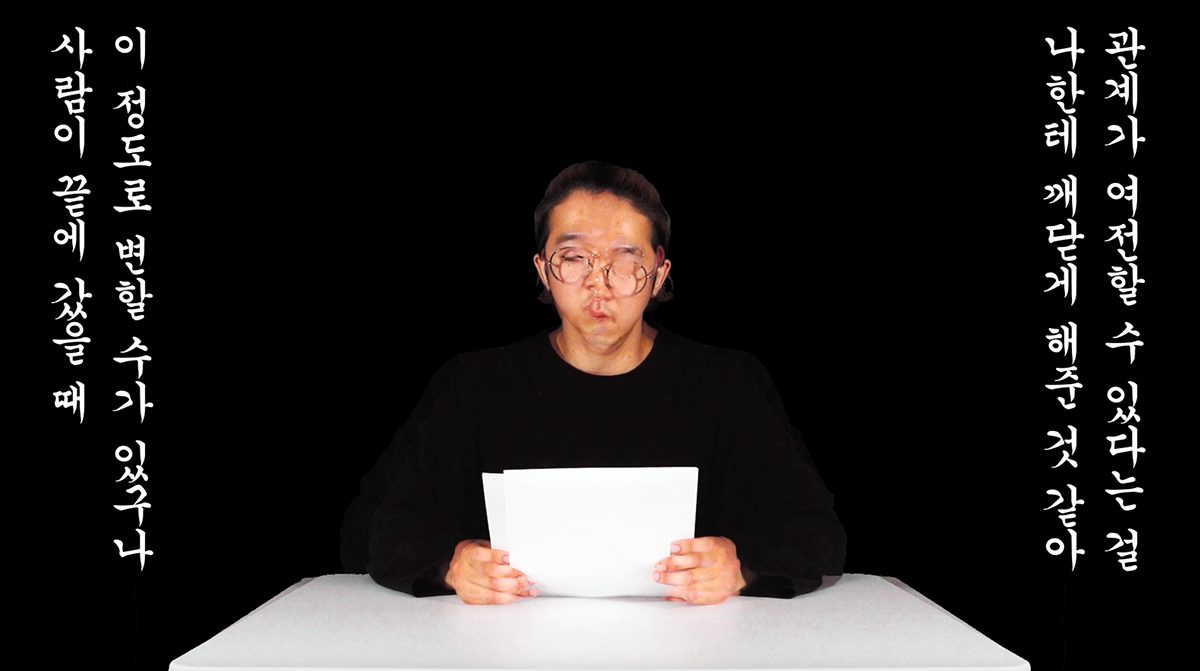

3. Contemporary Anxiety, Suspended Suspense

Daewon

Yun focuses on the state between “connection” and “contact.” This is not simply

a shift in media environments, but a proposition concerning changes in how we

sense and perceive the body today. As the expanded ubiquity of media

increasingly virtualizes physical bodily sensation, tendencies toward stitching

together reality intensify. In this process, ontological questions arise: how

should one define oneself within the boundary between reality and the virtual?

What kind of body is one that is mediated through screens? The artist reads

these questions as a sensory environment tied to contemporary anxiety.

Contemporary

anxiety is far removed from dramatic suspenseful events or clearly defined

crises. Rather, anxiety persists through gestures that do not touch, gazes that

do not respond. Connection becomes easier; contact grows distant. This

sensation—like a moment frozen just before something happens—may be called

“suspended suspense.” The moment of crisis has neither begun nor ended, and

this delayed, layered condition is precisely the symptom of anxiety we sense

today.

Joanna

Lowry has described projected images not merely as means of representation, but

as media that operate like “symptoms,” eliciting bodily sensation and

psychological response in viewers.* Yun’s performance confronts this suspended

tension—this delayed state of sensation—through the layering of physical

apparatuses.

The rotating projection device disrupts the sequence of screen,

body, and image, placing the audience in a space where temporal centers

disappear. When images of the “already-past body” intersect with movements

unfolding before one’s eyes, the viewer can no longer be certain which reality

they are encountering.

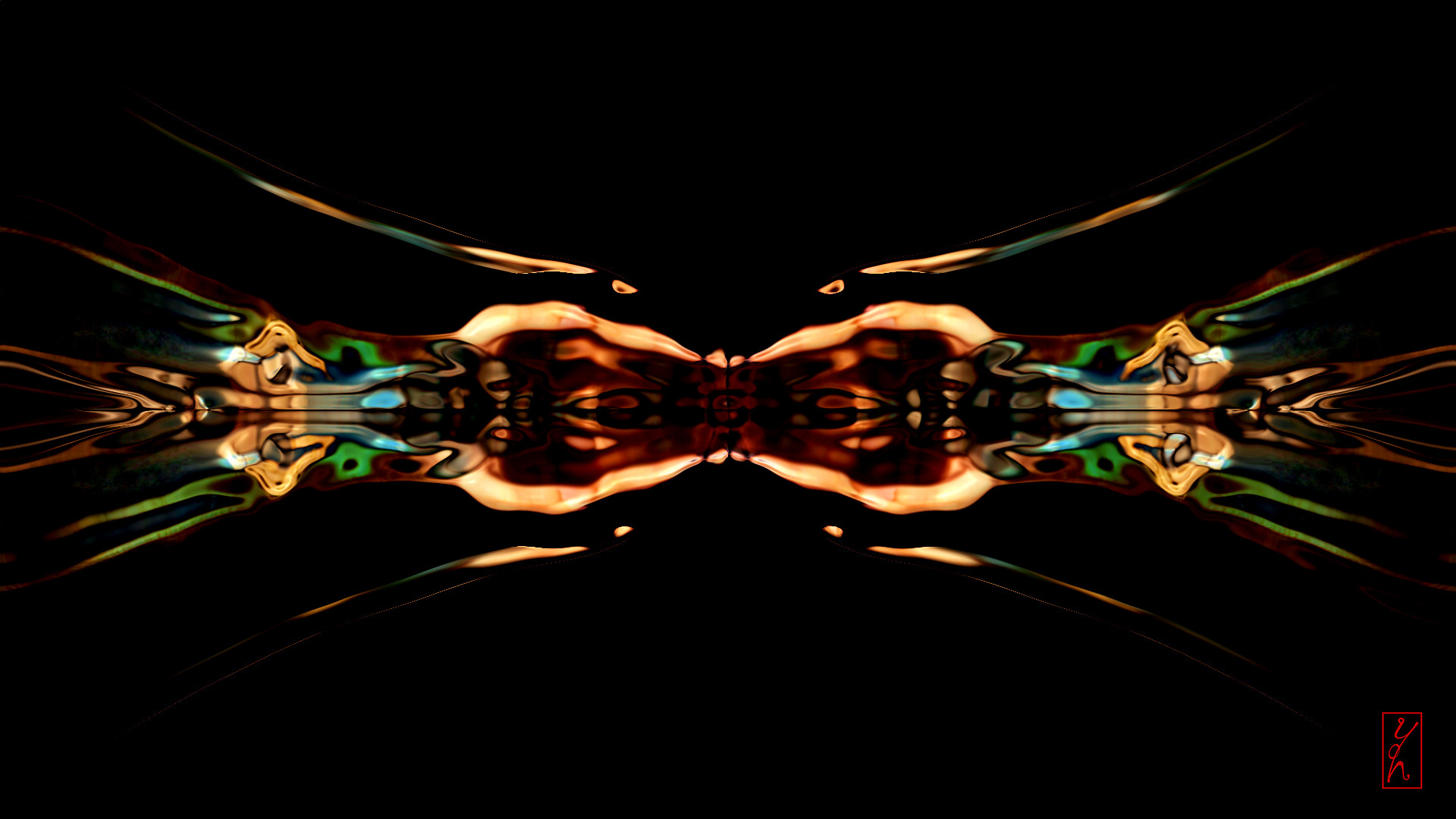

This

structure generates a new relationship between projected images and actual

movement. It turns presentation into representation, and then attempts to

reverse that process. Experiencing subtle vibrations between rewound forms of

past time and movements of the present, the viewer reconstitutes that vibration

as both a form of anxiety and a symptom of sensation.

Within

this unstable sensory environment, “connection” returns to physical sensation.

The moment projector light touches the body, it functions like heat. That

warmth lingers on the skin as a sign of anxiety produced by sensory delay,

image overlap, and misalignment between the real and the virtual. Within this

heat, subject and object are no longer fixed. The projected form illuminates me

while simultaneously gazing back at me; my body overlaps with another’s shadow

and becomes blurred.

The

moment of contact is not merely an act of touching, but a sensory situation

that suspends and inverts the boundary between self and other. Through this

inverted sensation, we perceive movement within the form of another, and within

the indistinct boundaries of the screen, we come to contact and connect with

ourselves.

*

Joanna Lowry, “Projecting Symptoms,” in Screen/Space: The Projected Image

in Contemporary Art, ed. Tamara Trodd (Manchester: Manchester University Press,

2011), 93–110.