0.

There

are moments when states we believe we know well—through frequent encounter or

familiarity—begin to slip away. The field of art sometimes transforms what we

call the “obvious” into a question imbued with doubt and fear. Particularly

amid the turbulence of digital technologies, our sensory understanding of the

physical and the immaterial readily falters, and hybrid subjects and situations

emerge with increasing prominence through layers of overlap.

As our bodies

strive to keep pace with the speed of change, they simultaneously expand and

sever the range of sensation. Moreover, the body as a condition that once

defined the individual through an independently recognized completeness

gradually relinquishes that absolute closure, coming instead to acquire meaning

through self-verification as a being entangled in relations.

Here,

Daewon Yun’s solo exhibition 《Circle, Chase,

Contact》 suspends sensory judgments between the real

and the virtual, layers bodies, and replaces the obvious with questions,

inviting us into an art space filled with apparitions. Indeed, the space was

full of apparitions. Layer upon layer of bodies and shadows, apparitions within

screens and mirrors, and between their contacts flowed our welcome to

connection.*

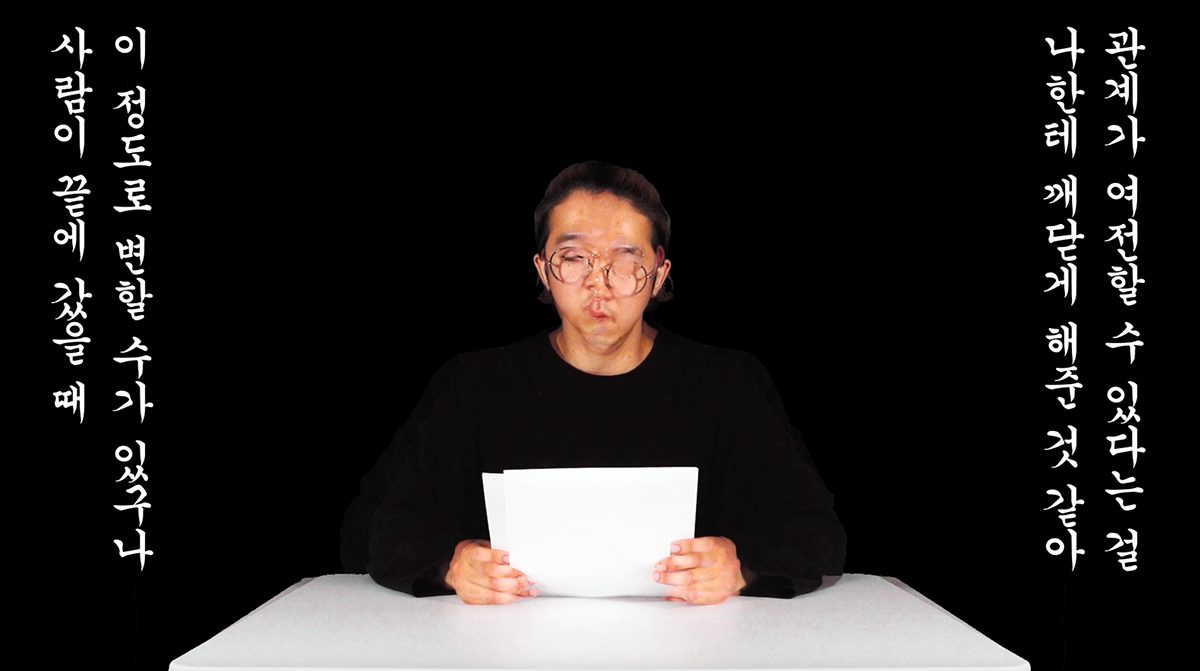

1.

Mediated

by the corporeal and technological conditions of “contact” and “connection,”

Daewon Yun reconstructs the sensory and perceptual conditions that surround our

bodies today. Here, “contact” and “connection” extend beyond concepts that

merely distinguish physical or technological relations between body and body,

human and human, or human and machine. Yun observes a state in which the

tactile sensations of actual skin-to-skin contact and encounters within digital

sensory realms are not clearly separated but instead coexist in hybrid form.

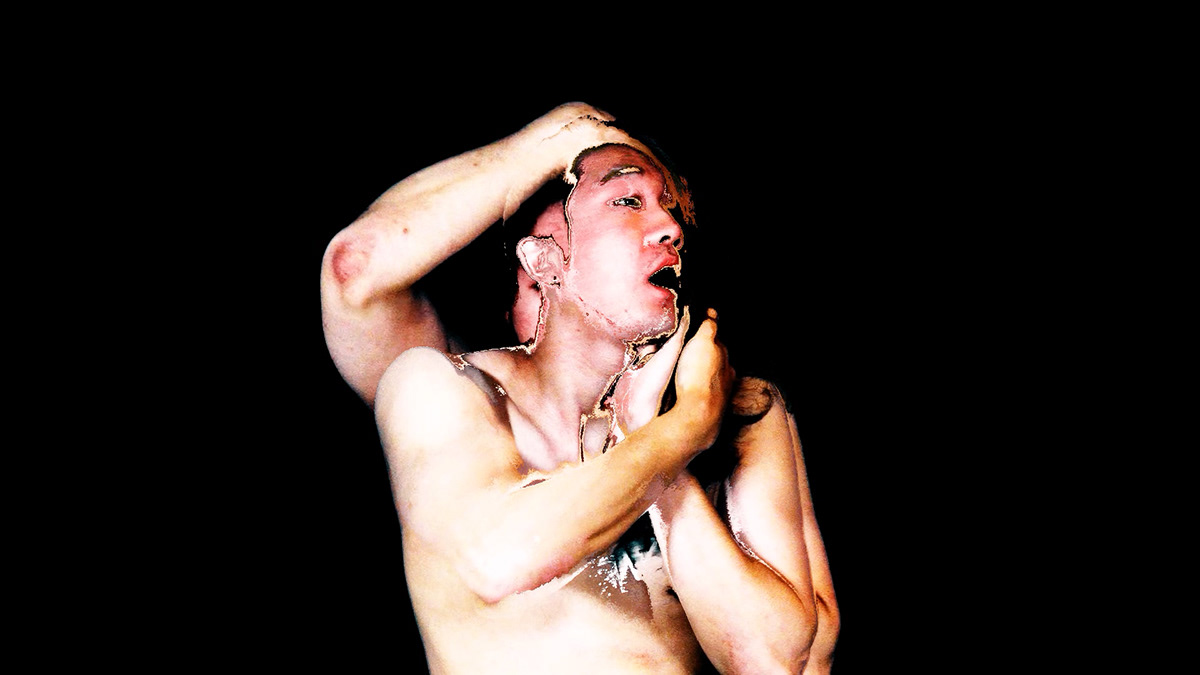

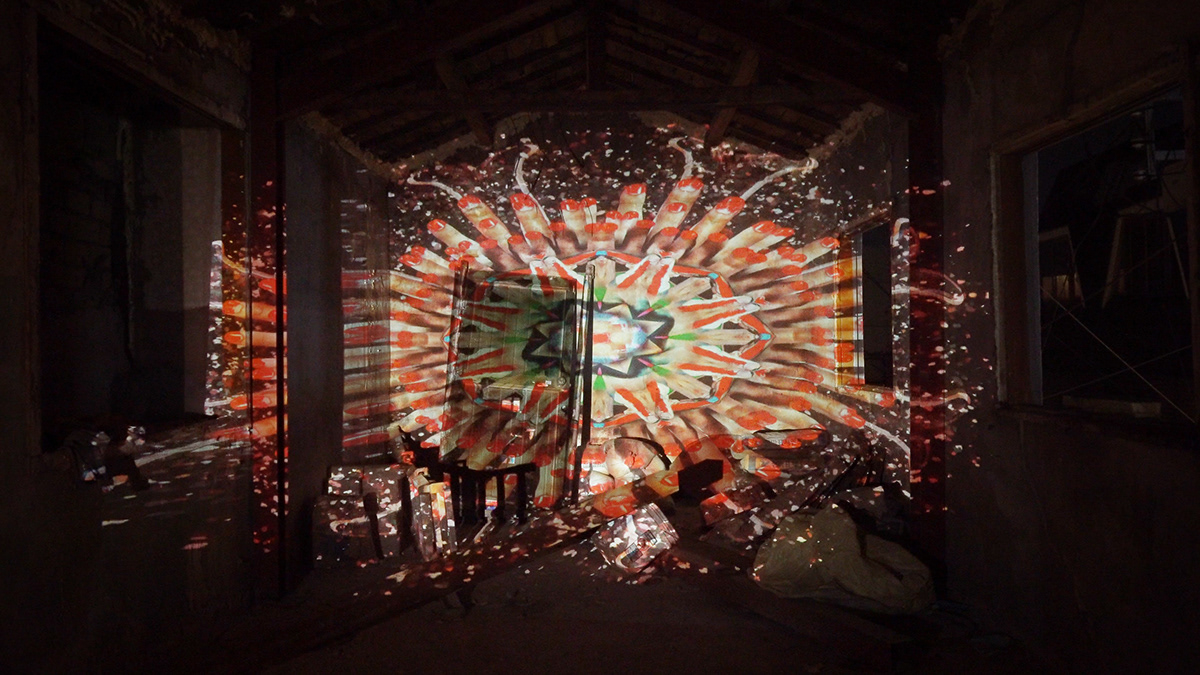

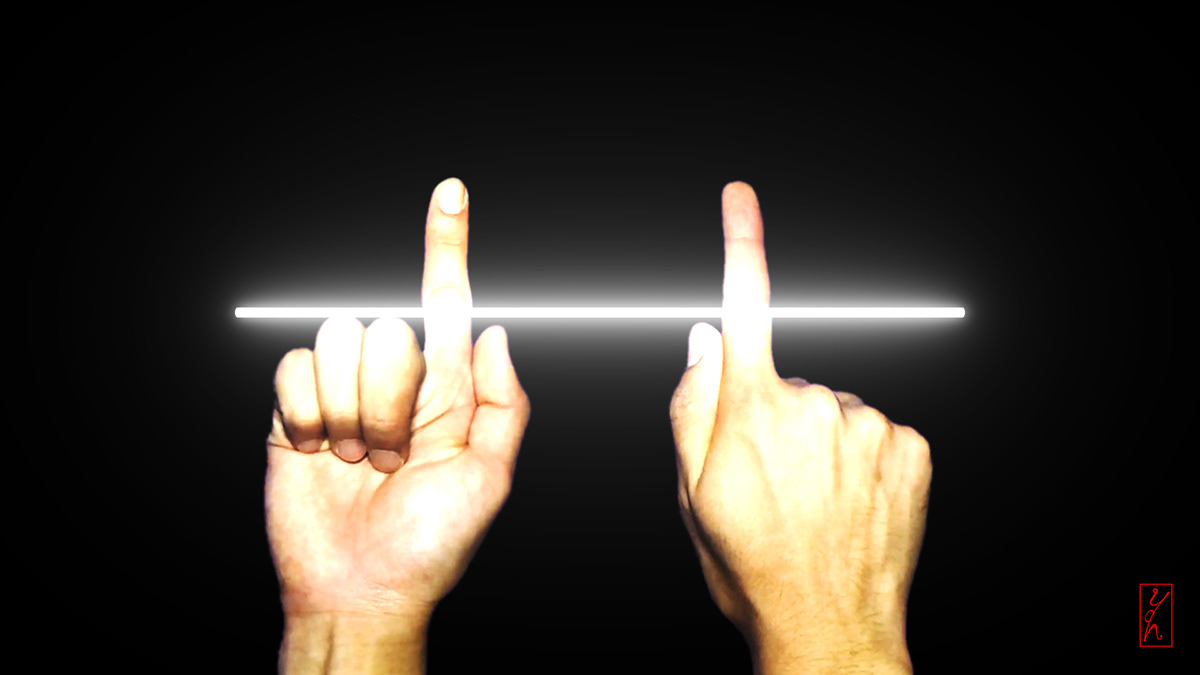

In

the unfamiliar world he unfolds, bodies are placed within a mixture of physical

contact and immaterial connection. At the center stands a towering projector,

rotating as it converts recorded bodies into light and disperses them.

Surrounding it are transparent fabrics, screens, and mirrors arranged in

reference to the bagua formation, along with lights in the five

cardinal colors, all holding their positions as structural symbols.

We enter a

space that is simultaneously artwork and stage. After passing through a

suspended time, we encounter four performers. The performers’ bodies and our

own continually interact with the world, searching for objects of contact or

connection; at times, contact and connection metaphorically substitute for or

transform into one another.

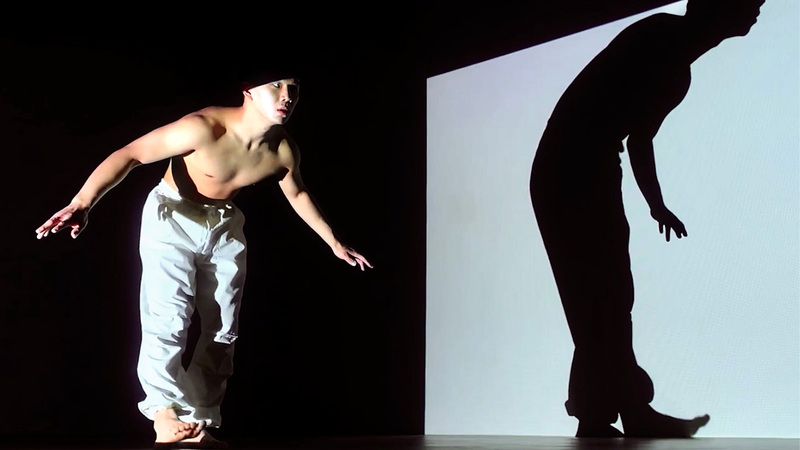

At

this moment, bodies are prepared as the most fundamental physical elements of

subjectivity. Depending on the direction of the rotating projector, recorded

bodies accumulate upon fabric and screens, performing chance encounters with

physical bodies. Shadows repeatedly disappear and reappear, while bodies

reflected in mirrors disperse and spread throughout the space. In this way,

bodies there repeatedly sense, contact, and connect.**

Contact

without contact, improvised contact, the gaze exchanged between eyes and the

projector, the radiating heat of dispersed beings, and our synchronized

connection. As performers repeatedly connect and disconnect, contact and drop

out, our bodies, faced with their challenges and initiations, break away from

possessed finitude and open toward the world. The frameworks surrounding our

bodies are reconfigured, giving rise to a slight sense of unfamiliarity and

discomfort.

This may stem from anxieties and isolation accompanying the

development of digital network technologies; or from the process by which

socially and culturally contact-oriented bodies are re-recognized as digital

bodies of connection in response to the expansion of new sensory apparatuses;

or from the perplexity of bodies that have slipped away from physical

environments into the blurred boundary between the real and the virtual.

Within

Yun’s invitation, which refuses to confine the body to a purely biological

frame, a chain of complex thoughts continues to unfold. Yun confronts as a

sensory reality of our time the very transformation of the body—fragmented by

digital technologies, dematerialized, and rendered connectable. Through his

work, we gradually come to accept that the body is not a fixed entity but a

state within relations, a mode of existence as connection. As our bodies become

open bodies, we encounter the subsequent scenes, momentarily setting aside

tangled reflections and beginning to grope toward the possibility of overcoming

individualistic alienation and restoring a sense of community.

2.

At

the core of Daewon Yun’s solo exhibition 《Circle, Chase, Contact》 lies “play.” As the

title suggests, it is composed through the contact (and connection) of two

long-standing communal games: ganggangsullae and tag. The movements

Yun devises are not limited to play as a device for evoking childhood sensory

memories. His approach to bodily movement does not merely realize an aesthetic

of formal motion. As he states, “dance is an act of liberation from primordial

anxiety,” and within his practice, the ritualistic potential of socially

constructed and perceived movements is expanded.

Whereas

his earlier works focused on patterning and imaging mechanically derived

movements of the body—extending and exhausting the body in the process—《Circle, Chase, Contact》 shifts its focus

toward movements that vocalize ritual gestures and collective emotions. It

expands emotional rhythmic synchronization of bodies into a ritual performance

aimed at the liberation of sensation.

The

method Yun proposes—“to experience contact in a way that is unfamiliar yet as

familiar as possible, and to feel oneself as part of a community”—is realized

through the formats of ganggangsullae and tag. Within the framework

of play, movement is not predetermined but decided through improvisation and

responsiveness. The movements of performers and participants overlap and

intermingle, rearranged within immaterial imagery through the rules of these

games, and enter the orbit of repeatedly shared emotional attitudes.

Movements

reminiscent of fern-breaking, hand-clapping and foot-stamping, roof-treading,

or gatekeeper games go beyond expressions of mere excitement or pleasure. They

become ways of constructing relationships—calling someone, catching, touching,

fleeing, and gazing—on the opposite side of solitary play. As roles shift and

the game transforms, we follow the performers and become subjects who hold

hands and run together. In these relational movements, contact becomes the most

primal medium of sensation, and brief encounters and eliminations leave behind

a desire for new connections.

Ultimately,

the communal worldview of Korean tradition unfolded by 《Circle, Chase, Contact》 proves neither grand

nor distant. The worldview of community encountered through Yun resembles

childhood—meeting friends without firm plans, inventing games on the spot,

running and playing until dusk settles, and heading home at a parent’s call,

leaving behind an open-ended “See you tomorrow!” Without calculating right and

wrong, gain and loss, or relational accounting, we find ourselves liberated to

become friends even with those we meet for the first time.

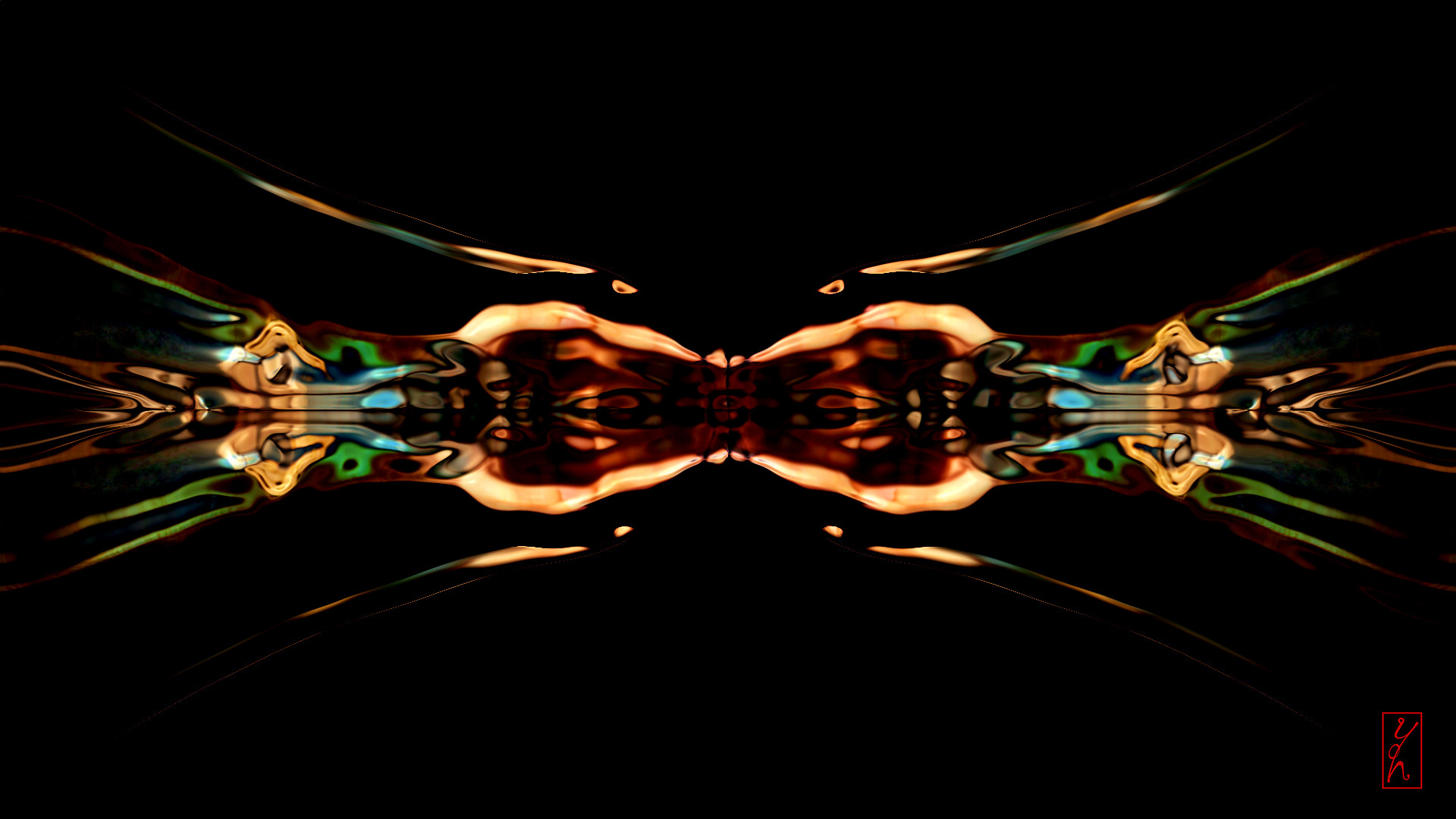

Within

that liberation, the rhythmic overlap of the real and the virtual—realized

through the coupling of projector movement and digital technology—recedes into

a sensory backdrop, while the center of time and space gradually shifts from

thematic structures to our bodies. Through 《Circle, Chase, Contact》, Yun reveals the

concern that “digital culture unsettles the body and generates unstable

sensations,” yet he simultaneously accepts the state of technological media we

face as a natural transformation of the sensory environment, exposing the

questions that drift along with it.

The art space he constructs presents our

bodies not as fixed entities but as variable, relational states. There, we

simply run and play, anticipate encounters and tomorrows, and hope. And those

invited gradually become the protagonists of play, and the owners of the space.

In this way, Yun’s field becomes a sensory laboratory that moves beyond

nostalgic aims derived from body and community, toward re-sensing the body and

rethinking togetherness under contemporary conditions. It is filled not with

critique but with reflection, not with regression but with recovery.

3.

Daewon

Yun’s solo exhibition 《Circle, Chase,

Contact》 consisted of 19 performance sessions over

seven days, along with one artist talk. According to the artist, the project

aimed “to expand the boundaries between traditional performance and media art

through the characteristics of multidisciplinary art that combines diverse

genres and media.”

In this sense, it may be more accurately described as

multidisciplinary art, performance, or live art rather than an exhibition.

Notably, however, official promotional materials continued to refer to the

project as an “exhibition,” producing a subtle tension by deviating from the

conventional grammar of solo shows that typically presume single authorship and

gallery-centered modes of viewing.

Yun

thus assumes multiple roles: artist, planner of a multidisciplinary art

project, and designer of the exhibition-viewing experience. Particularly

noteworthy is his strategy of designing the conditions for viewers’ sensory

immersion through the structure of performance, positioning our bodies and

attitudes as interfaces. This constitutes a central strategy and methodology of

the project.

In

contemporary commercial technologies, the configuration of an interface

radically shapes narratives of function and structures of sensation. An

interface extends beyond a mere control panel; it is a device that opens

possibilities for connection and sustains environments of contact. Yun

transposes the concept of the interface into an artistic methodology. In other

words, he proposes a new “interface of perception” at the intersection of

technology and sensation.

This interface is concretized through performers’

bodies and completed through the audience’s senses. Not only physical bodies,

but also the will to sense, the attitude toward immersion, and the state of

blending into space—all become interfaces.

While,

in technological history, an interface mediates functions between user and

system, in Yun’s work it becomes a device and attitudinal frame that induces

tension and collaboration between body and sensation, media and perception.

Consequently, audiences are placed in multiple states: they may simply watch,

participate, gaze, or immerse themselves, operating as beings that tune sensory

frequencies. This structure exceeds participatory art, demanding a

transformation of sensory attitude itself.

Before

the performance begins, a twenty-minute period of suspended time symbolically

reveals the preparatory structure of this attitude. Before performers’ bodies

appear, the central projector, transparent fabrics and screens arranged

in bagua formation, mirrors, and five-colored lights occupy the

status of the artwork itself, prior to becoming a stage.

These material objects

function as omens of the scene to come, as sensory warm-ups, and as intervals

between pre-connection sensation and imminent contact. Here, Yun’s work expands

beyond media performance into the design of a sensory environment. Audiences

prepare themselves as a potential community, readying their attitudes for

immersion. This silence becomes a key to understanding the structural rhythm and

spatial sense of the ensuing performance.

The

performance unfolds in two parts. In Part I, the movements of four performers

appear fragmented among images and shadows projected onto fabric, screens, and

mirrors. Amid excessive visual information and heterogeneous temporalities,

audiences abandon single-point perception, turning their heads, moving between

scenes, adjusting flows, and reconstructing coordinates of sensation. Sensation

here is no longer natural but an effort that must be continually perceived and

tuned. While this information-rich structure may at times induce unstable

immersion or stalled movement, its intent becomes clear as Part II begins.

In

Part II, audience movement is incorporated into the stage, revealing

retrospectively that the earlier stillness and gaps were conditions of sensory

preparation. No longer peripheral others, audiences become subjects of

sensation within the structure, experiencing how their bodies generate meaning

through processes of contact and elimination. The forms

of ganggangsullae and tag symbolically realize this structure of

sensory connection. Holding performers’ hands, running together, searching, gazing,

and fleeing, audiences retrain patterns of sensation.

In

tag, subjects exchange positions through contact,

while ganggangsullae invokes collective emotion through repetition.

Toward the end, all participants—who had been playing both separately and

together—join hands, forming a single rotating circle. The four performers,

once challengers and initiators, quietly exit one by one. There is no longer

any need to read cues or follow others. The communal play now sustains itself

autonomously through the audience’s bodies.

This

scene is not a simple reenactment of play, but a strategy that reverses the

immaterial interactions emphasized by technological media into bodily affect.

The performance thus becomes not a question of “how to represent community,”

but an experiment in attitude asking “how community can be sensed.”

This

experiment extends into the collaborative process itself. The movement

designer, sound designer, and four performers are not merely collaborators;

they participate in the artist talk alongside Yun as equal contributors.

Notably, the sound designer collected non-contact sounds generated by the

resonance of a gayageum with wind, and after each rehearsal and

meeting, participants shared their sensations and progress through a

collaborative web page. This functioned not as simple online connection but as

a structure of contact without contact, synchronizing attitudes and rendering

each performance a unique sensory event through improvisation and repetition.

Within

a ritual structure that repeats yet never remains identical, Yun explores the

rhythms of sensation generated by multidisciplinary art, seeking to invent new

modes of connection between body and technology, community and attitude. The

sensory structure he designs lingers with us even after the viewing ends—not

merely as an afterimage or memory, but as a question of how we might continue

to keep our bodies open in everyday life. Thus, art sometimes quietly activates

an attitude no one demanded, gently inclining our bodies toward others.

*

The ambivalent term “apparition/welcome” (환영) is borrowed from the introduction of the exhibition preface

written by Jihee Yun.

** Maurice Merleau-Ponty considers sensation to be a moment-by-moment

“re-creation and re-composition of the world.” The art space Yun unfolds

reveals the expressive capacity of the body, and his conception of art may be

understood as the encounter between subject and world, and the process of

recreating and recomposing the world beyond that encounter. Merleau-Ponty’s

assertion that “artistic expression gives what it expresses an existence in

itself, arranging such self-existing entities within nature as objects

accessible to all of us” also comes to mind. Yun translates contemporary

conditions of perception and existence derived from corporeal and technological

circumstances into the keywords of contact and connection, arranging even

himself—following Merleau-Ponty—as an object accessible to all within nature.

Through this, we are positioned to grasp ourselves as one aspect of existence

within the field of encounter between subject and world, and within the process

of recreating and recomposing the world. See Nam-In Lee, Husserl and

Merleau-Ponty: Phenomenology of Perception (Paju: Hangilsa, 2013).