Street Woman Fighter and Daewon Yun

One

of the reasons Street Woman Fighter (hereafter SWF)

attracted such extraordinary attention may be that its protagonists were doubly

othered figures. They were not institutional dancers, but street dancers—and at

the same time, women. In the way they spoke, dressed, and danced, a distinctly

non-institutional resistance remained intact, something rarely seen in

conventional competition programs.

By

contrast, Korean ink painting (hangukhwa), rooted in China and constrained by

tradition, has long struggled to encounter contemporaneity, which demands a

rejection of the present while oscillating between the “already” and the “not

yet.” In this sense—particularly within university education—hangukhwa can

be said to be doubly othered: both from its own past and from contemporary art.

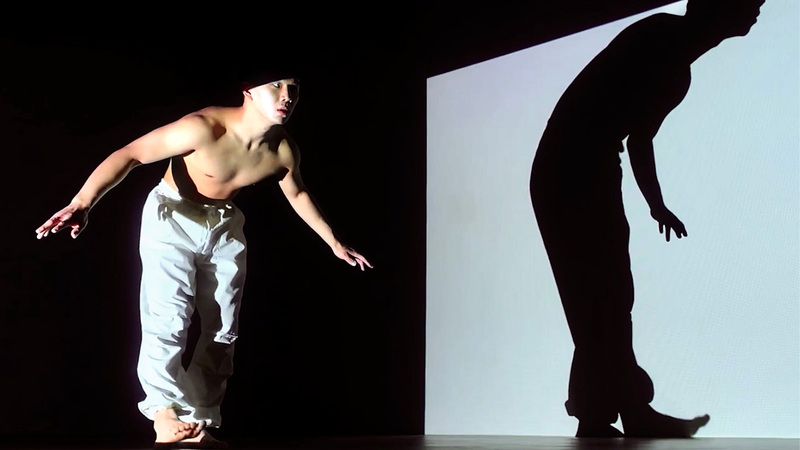

Daewon

Yun is a former street dancer who also majored in Korean painting. For him,

street dance may have represented a “young body” that one is almost inevitably

forced to abandon with age. Meanwhile, in the digital moment of 2021—when the

Seoul Metropolitan Government declared itself a “metaverse city”—Korean

painting could likewise appear as an anachronistic medium or aesthetic that one

might naturally fold away.

At

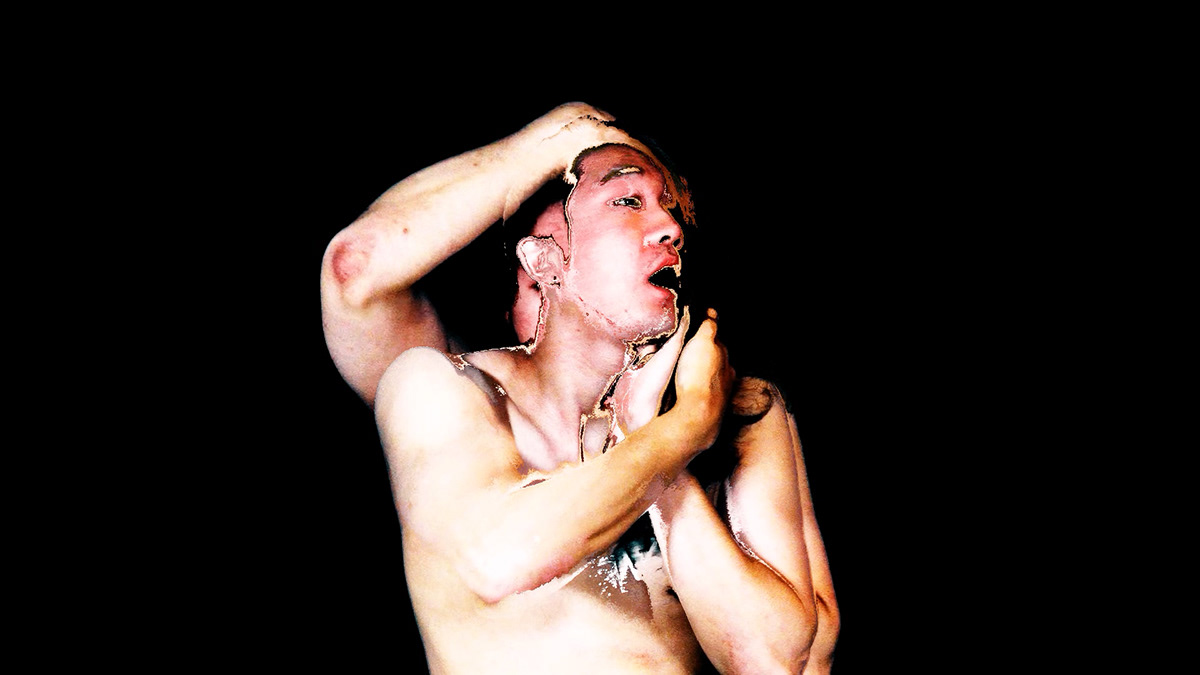

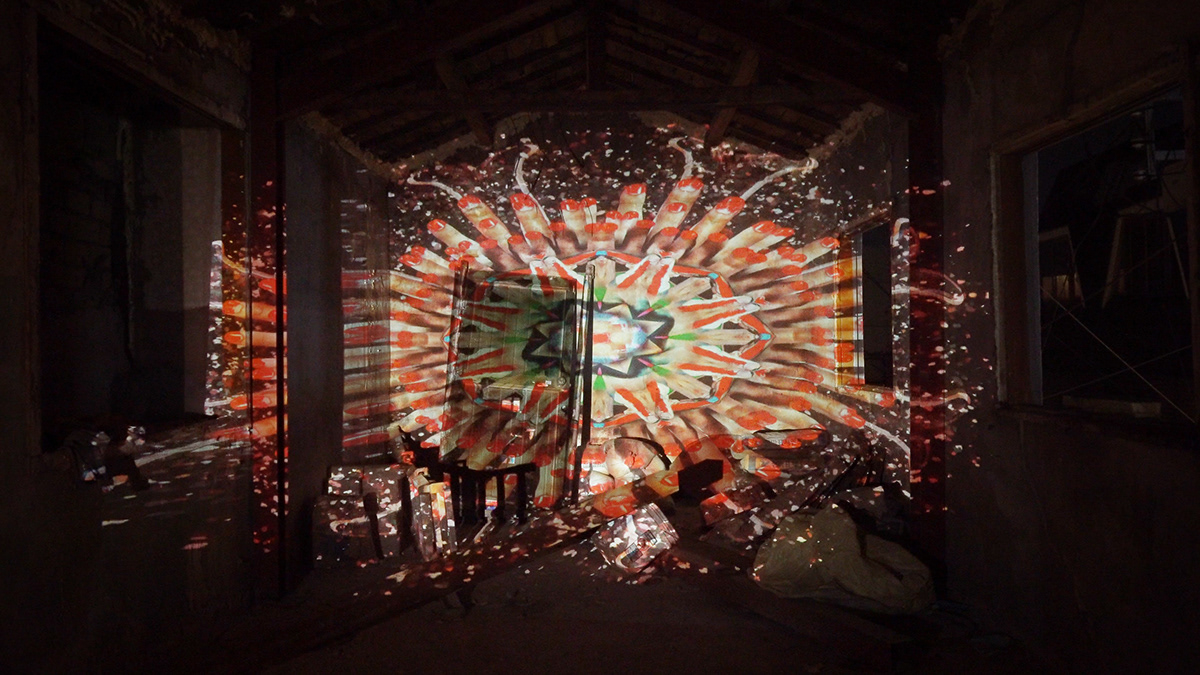

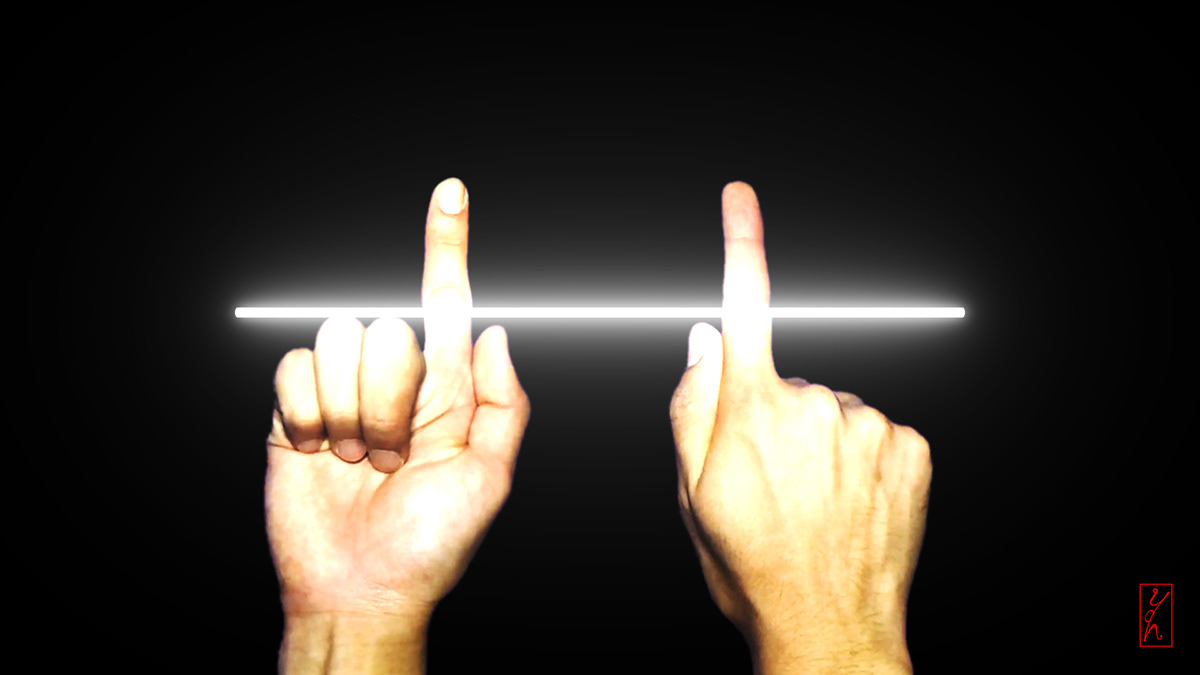

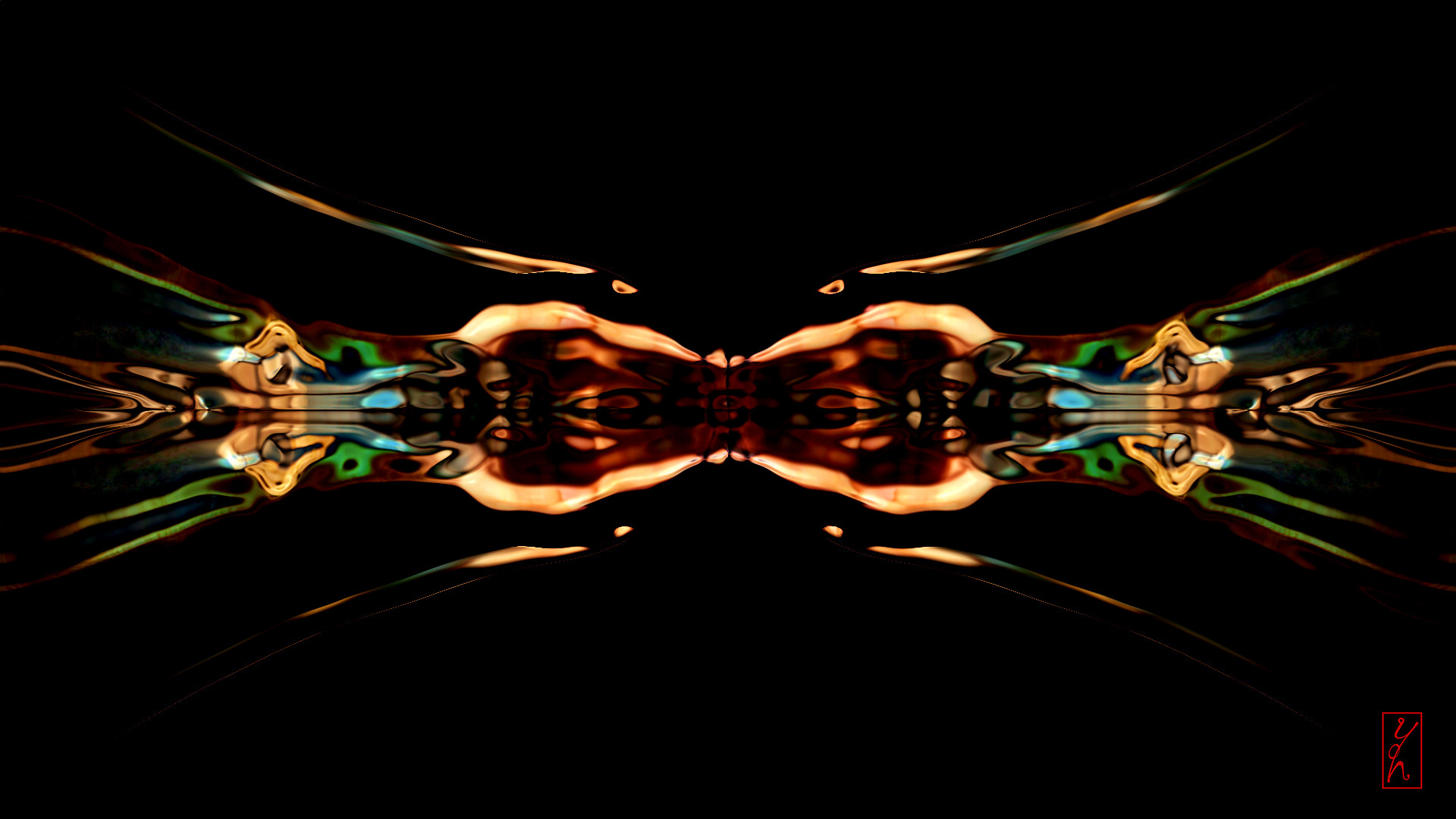

his solo exhibition at Hanchigak, digital graphic videos and NFT works are

presented—befitting a young artist in his twenties. The ‘Virtual Body Lab’ video

series includes Yun’s own body and movements, yet the body of the street dancer

is erased, replaced by a body that conforms to digital signs. This develops

into graphic videos reminiscent of a kaleidoscope. A “body that conforms to

digital signs” suggests a fragmented and distorted body that fits seamlessly

into the digital or virtual world.

If

the aesthetics of contemporary art favor dissonance over harmony, instability

over stability, shock or discomfort over visual pleasure, unease over comfort,

and negativity rather than positivity, this cannot simply be praised. Yun’s

strategy—his idea—of “repetition” has been familiar since Andy Warhol, and

“distortion or transformation” has long ceased to feel unfamiliar or novel

since the Surrealists.

Of

course, repetition, distortion, and transformation remain strategies frequently

employed by contemporary artists. The question, then, is at what point these

strategies become justified for some artists, yet have their legitimacy

questioned in Yun’s case. Earlier, Yun’s strategy was referred to as an “idea.”

If we insist on distinguishing idea from concept, then an idea is what carries

a concept forward.

First,

we must ask: for what kind of concept was this idea adopted? Second, how do

these ideas connect to the contemporaneity we inhabit—no longer the era of

Warhol or Surrealism? These may be harsh questions for a young artist just

debuting, but if we agree that irreducibility to anyone else is the highest

virtue of an artist, then these are questions Yun must prepare to answer.

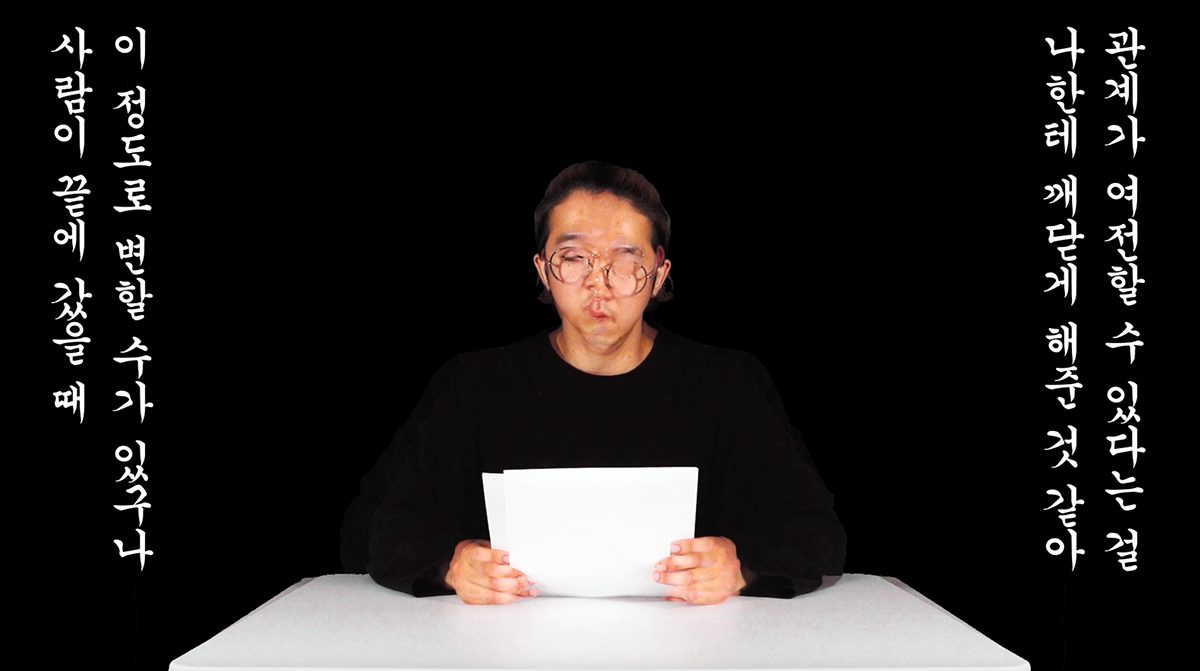

Yun

states that although the NFT video was sold, he does not know exactly who the

buyer is. Paradoxically, the most interesting work may be NFT-BODY COIN,

the only work in the exhibition that was financially compensated. This piece

does not deny that it itself is a form of virtual currency.

1.

The artist does not know who the buyer is.

2.

The image of a cryptocurrency was sold and paid for with cryptocurrency.

3.

The work was sold, yet remains exhibitable.

Although

it is the most commercial work, this sequence is paradoxically new and ironic.

For some, this situation may appear “uncomfortable,” “unstable,” or even

“abnormal.” For a young artist in his twenties debuting in the art world, it is

natural that video, digital media, virtual space, and NFTs—already common

media—are recognized as appropriate means of approaching contemporary art. The

issue is precisely that these media are already normalized in

contemporary art.

Amid

countless artists using the same media, and within kaleidoscopic and

mandala-like imagery already extensively explored, how can Yun’s work avoid

dissolving into one among innumerable anonymous forms within the mandala?

Perhaps Hanchigak, located in a market alley in Pyeongtaek—a peripheral

counterpart to Yun’s Itaewon—poses this very question to the artist by boldly

selecting a young artist through its open call.

The

market alley in front of the U.S. Air Force base in Pyeongtaek, where Hanchigak

is located, may be one of the places most distant from contemporary art in the

Seoul–Gyeonggi region. In a neighborhood largely populated by soldiers or those

connected to military-related industries, it is rare for passersby to casually

visit and engage with the gallery’s curation.

By contrast, Yun’s

Itaewon—sharing a similar historical origin as an entertainment district near a

U.S. military base—has developed a markedly higher level of cultural and

artistic sensitivity, arguably among the highest in South Korea, from the Leeum

Museum to Space and Hyundai Card Concert Hall.

Encountering

Yun’s work in a remote corner of a Pyeongtaek market alley, far from Itaewon,

seems to demand from us a degree of “distancing” equivalent to that between

Itaewon and Pyeongtaek.

Giorgio

Agamben, who defined contemporaneity as existing between the “already” and the

“not yet,” further explains that a contemporary person is one who “adheres to

the present while simultaneously rejecting it.” Itaewon acquired its resistance

through othering, much like SWF. This would not have been possible without

the distant presence of U.S. military culture. SWF’s aesthetics were

possible precisely because they stood far from the polished idol aesthetics of

mainstream broadcast television.

Might

it be possible, then, for Yun to forge a connection—from what has seemed most

distant to him, such as the street body (street dance) or traditional

painting—to video, digital media, virtual space, and NFTs? Just as taking

distance allows one to clearly grasp the terrain and position of one’s home

when viewed from Namsan, perhaps this distance is what Yun’s work now requires.