Inside a black box, a looping hummed tune, not ending, not ending,

not ending, an approaching early morning, someday, a morning without teeth, a

morning without a tongue, a morning without arms, a morning without fur,

someday, a morning with nothing, a morning without morning, again, being born,

coming in dreams, coming into paintings, again, coming in winter, coming in

spring, again, not dying, not living, not sleeping, not waking, again, not

speaking, not fumbling, not crying, not wailing, with wide eyes, climbing the

wall, with the sound of a baby crying, not disturbing the night’s sleep,

now

raise the morning, hang the morning, strike the morning down, a discarded

buttock, a dawn-breaking buttock, that damned little buttock, scoop up that

soggy pit, until it rots, until the cause of death fills the livor mortis,

until it turns bluish on the electric blanket, until it cools like an ice

candy, until it swells like a sad caterpillar, this thin sound, the sound of a

dog dreaming, the sound of a gentle dog with its eyes closed, the sound of

spilling souls, shedding fur, loosely shedding, the sound of spilling

existence,

a sound that does not disappear no matter how much it spills, the

calm of bone and flesh, a sound rolling like blue marbles, the sound of the sky

collapsing like a tunnel, the sound of the sea flooding like rainwater, in

spring, the sound of heavy snow falling out of season, again at midnight, the

sound of searching for a child, shitting and licking and walking and crawling,

walking and crawling and lying down and being cold,

a navel-less belly faces the sky, faces the sky, faces the sky,

not sky but ceiling, not greeting but farewell, not a rosary but prayer beads,

not a diary but a letter, not a letter but a will, dying, again, early morning,

softening, sinking in like cake, again, ma,a,a,a, the sound does not rot here,

sinking like this all along, again sinking like this unawares, because time

only flows, the child left behind, the searching sound, the soul-searching

sound, like this all along, helplessly like this, apologetically like this,

brutally like this, with a loose laugh like this, absurdly like this, the songs

of the dead, old songs that bring misfortune to no one, in a dream,

only open

doors line up with mouths agape, in each compartment, sitting cross-legged,

smacking their lips, gatekeepers in front of the main gate, knocking on

windows, knock all the windows, no windows, all the windows smashed and gone,

again at midnight, the sound of searching for a child, the sound of trembling legs,

finally, cover the mouth, so it won’t snore, seal the lips with tape, never

again the smacking sound, an endless appeal, an endless confession, an endless

light sleep, an endless line break, again like this, at midnight, alive, a

four-legged bed, a four-legged bathtub, a four-legged dog, the sound of breath

clinging on, the sound of fleas leaping while alive, again like this, this time

for sure, never again, never like this, absolutely,

period, end after period, period, end after period, period, end

after period, period, after that it is over, at some someday without even a

chance to speak, without any autopsy it ends, clouded eyes, a blocked mouth,

spread legs, end, hair fingernails toenails growing, end, a ruined end knot, an

endlessly ruined end knot, a cliff slope a single barbed-wire tree, end, lips

anus, end, a burning temple black ridgeline chirping scops owls bloodshot

trumpet creepers, blinking blind eyes, deaf ears, hands severed at the wrists,

feet severed at the ankles, thrown far away, end, making a U-turn and coming

back, end, parked, end, crossing the threshold without ringing the bell, end,

standing blankly, end, with a familiar expression, end, returning home, end,

from where, end, hacking and spitting out a neighbor’s phlegm, end

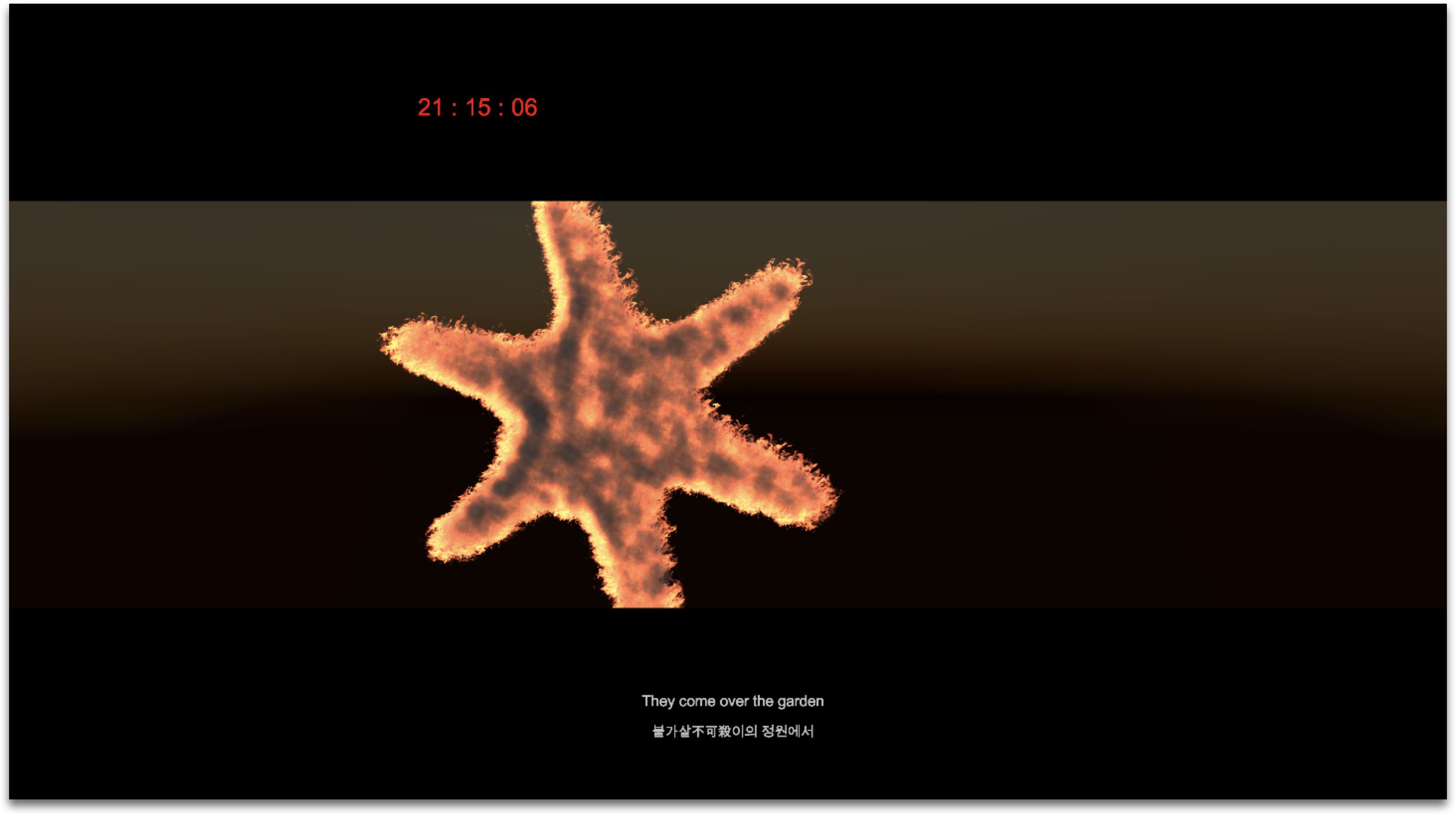

What is invited here are bodies that remain / still / not yet

here, and bouquets vividly standing still like hearts in which time does not

flow[1]. I prepare places where flowers will hang, using drawing paper,

mulberry paper, fine paper, mounting paper, photographic paper. I recited

Un-hee, read Teresa, and bring in a grotto.

February has many graduation ceremonies. Graduate schools and

daycare centers alike hold graduations. Flowers drink water with severed roots,

and their passageways gradually collapse. The poet smells the stench of death

in a bouquet. The dog barks every early morning like an alarm clock. The bed

stands on four legs. The door has four corners and opens and closes. The yellow

light-shadow falling from the window also has four corners, yet tilts

diagonally as if emphasized in italics. Snow falls even in spring.

I first examined post-mortem changes, injuries, neonatal and child

deaths, and deaths caused by sexual crimes. Suffocation, drowning, poisoning,

and starvation followed. Familiar chapters become so clear that I memorize who

lies on which page, and yet unfinished, unworked corner windows jut out here

and there. There are those I end up drawing many times. At first, I even

thought the difference in frequency was unfair, but becoming friends is, after

all, a matter of faces drawing closer than everything else that is not a

friend.

Because most reference images in forensic books are small, repetition

reveals shapes that were not previously distinct. What I thought was a stab

wound becomes an eye; what I thought was a spine becomes an umbilical cord. I

feel a strange obligation to draw every page. When I am consumed day and night

by transcribing them, sleep is no longer rest but a kind of defenseless

connection. An unseen, unheard white dog comes into the house, and from the

moment I decide to become its guardian, sleep paralysis stops as if by a lie.

The white fur of an albino boy born without kin begins to settle throughout the

house. Even in a pitch-black corner of the studio, it naps calmly as an

unshadowed white light.

Recently, the reservoir inside my body overflowed[2]. It was when

I went to see “Baekyang-daero[4],” which I learned about through an online

Busan Ilbo article[3]. It is a drawing series by artist Park Jahyun depicting

side doors of a red-light district; though the doors appear closed to the eye,

if you stare blankly at them they keep opening. Not long after arriving at the

exhibition, my foot cramped. I tried stretching by lifting my heels as if

wearing high heels, but that day the wriggling did not stop, instead climbing

my calves and thighs and winding all the way around my fingers.

So now I am

being paralyzed while awake, I thought, and that bodily state has continued

throughout early spring since that day. All ten fingers jerk stiffly, both feet

spasm, I have only one head, and my whole body is trapped in a vivid state of

paralysis. This used to be a side effect I experienced only while attending

Professor Yang Hyosil’s lectures. I think: if my wrists and ankles are being

held this mercilessly, I want to stop feeling anything at all. But such things

were always already there.

Soon I imagine forms of invisible contact at the

extremities. When my ankles throb, is it telling me not to stand upright like

this? When the knuckles holding my pen stiffen, is it telling me not to draw

the bodies I was drawing? Or is someone tightly interlocking fingers with me,

asking me to draw them more vividly? I take some medicine, support myself on

two arms and two legs and hang from the indoor climbing wall, so that the

recovery pain of injured muscles surpasses the paralysis pain, and the

wriggling slowly returns deep inside the body.

They say the eyes are the windows of the heart. When eyes meet,

windows become side doors opening layer upon layer, and when eyes close, a

dream repeats the scenery of countless gates lining a closed street—it is an

evicted landscape. And now voices can be heard. Here, voices are a kind of

collage. They speak only in citations. For instance, while I alternate between

drawing autopsy photos and scene photos, YouTube autoplay informs me that this

was a case in which two babies were frozen immediately after birth due to

pregnancy denial.

Soon after, while reading a poetry collection, I hear them

whisper, “……When I was born, I was inside a refrigerator[5].” Or I notice the

clarity in the voice that reads this exhibition title in French, “Le bouquet

est toujours là.” The frozen children are hard like stone totems. This is

different from hardness (dure). Soon, when friends with soft (doux), mushy

(mou), plush (moelleux), bitten-through[6] faces look down at me, even though

there is no dagger or hostility directed at me, the mere fact that unreachable

dimensions touch electrifies everything.

Beneath their tingling pity and

caregiving paralysis, I simply share with them my dead father’s flesh—or the

living daughter’s time. If everything is a matter of time, I devise ways to

endure hot, dry time. These ways are born from the boundaries and rules learned

through contact with the dead. I wait for everything to be erased, neither too

fast nor too slow.

A bundle of skull bouquets, a bundle of genital bouquets, the

bouquet

still does not even think of rotting, blood and tofu

honey cakes and blood cakes where crushed bodies cling together,

who

is writing poetry, who is writing poetry with stones in their

gallbladder

on asphalt, with intestines, who is grinding the shredder

gnashing, you are residue of language, residue of holes flowing

from hole to hole, who

is writing poetry, pupils that cannot be closed

even with needles, bloodshot fish eyes biting into

a crooked smile, a bundle of skull bouquets, a bundle

of genital bouquets, who is spinning for a thousand years

inside a revolving door, inside a twenty-liter pay-as-you-throw

bag

the bouquet still does not even think of rotting

Kim Eun-hee, “The Bouquet Is Still There”[7], full text

The deaths I have witnessed are my father, grandfather, dog,

sparrow, pigeon, snake, mouse, and countless fish, insects, trees, and flowers.

When vivid scenes form as if already seen while listening to accident reports

on the taxi radio, this work of transcribing opened bodies seems to function as

rumination and rehearsal for every death witnessed before and after.

Or perhaps

it leaks the truth that a body that has endured trauma becomes absurdly

fascinated by injured bodies. These days, when I walk down the street, I grimly

imagine two versions of strangers I do not know: their ruined form, and their

form writing poetry with a face no one can know.

Text: Cha Yeonså

[1] Cha Hak-kyung, Dictee (translated

by Kim Kyung-nyeon, Eomungak, 2004)

[2]“Reservoir, ruffled // waterbed of / the drowned // a corpse drunk on water,

water drunk on a corpse, a corpse / drunk on a corpse, inside the corpse / another

corpse / sings”, Kim Eun-hee, “Reservoir,” in That Woman Sleeping

Under a Withered Cherry Tree (Minumsa, 2011)

[3] [Art Inspiration] Artist Park

Jahyun (Busan Ilbo, reported by Oh Geum-ah, 2023)

[4] Park Jahyun, solo exhibition 《I Like My Life》 (curated by Lee Jin-sil,

Hapjeong District, 2024)

[5] “……When I was born, I was inside

a refrigerator // they say a buttock hanging from a hook gave birth to me, but

what kind of buttock it was, no one seemed to know”, Kim Eun-hee, “When I Was

Born,” in Trunk (first edition 1995, Munhakdongne;

revised edition 2020)

[6] “Let’s sing, with half-bitten / bitten-through

faces // a mad, love song”, Kim Eun-hee, “Savage, Savage,” in That

Woman Sleeping Under a Withered Cherry Tree (Minumsa, 2011)

[7] Kim Eun-hee, An

Unexpected Answer (Minumsa, 2005)