Who

might undo the law-symbolic language? Who resists humanization while being

utterly unaware? Who crosses the world of adulthood without barely/narrowly

losing the child-like senses as a non-human, post-human? A child recognizes a

grandmother or ghosts in reverse order. They're alike. Feeling as though some

things are so delicate that they make you want to break them—is akin to the expression of wanting to embrace a child.

To prevent

a child from seeing the terrible things yet to come, perhaps it would be

necessary to break the child, or because children are a future that came early,

I wish to touch them out of gratitude. A child is similar to an artist or a

madman, or people who are sick and lack social utility—or

because they may not grow up to be those types of people, they could prove to

be socially useful. Come to think of it, a child is precious to everyone.

Asked

to contribute a short piece of writing about Cha Yeonså's work for this

exhibition, I should note that I had been invited to participate in their

previous live performance called Mosquitolarvajuice and was

filmed reading Aglaja Veteranyi's passion play about children. According to

Yeonså's categorization, I guess I would be a larva with a "younger soul,

regardless of age."

Appearing as a duo during the performance, Kim

Geumone, standing in as Yeonså, and Yeonså's mother, Sohn Nari, reciting Sylvia

Plath's poem, were those types of larvae. Because this text has been produced

by someone welcomed by Yeonså, the director, who provided a stage for the

larvae they have recognized and assigned them roles they deserve—I don't think it can be considered a critique. In any case, critique

is a public gesture written with the premise of a certain distance, but I am

too close and connected to Yeonså. By the time I left Yeonså's apartment—where they use one room as a studio—I felt

like a squishy bug, a munchy lip, a soft brain. Wet and infected.

Researcher

Sohn Nari, Yeonså's mother, mentioned she used her studies on Sylvia Plath to

talk to Yeonså when they were even younger. In hopes of conversing with her

daughter, who seemed too weak to survive—perhaps almost refusing to live—she used the

language of a so-called “unhappy” woman's sensitive, violent, accurate poem as her 'mother tongue.'

Yeonså's sentences, which you will now read too, are unfamiliar and beautiful.

Or, it's a poem of the non-ego 'staring' at the world of differentiation.

Regarding the mosquito included in the titles of the past two live

performances, Yeonså described them as "a very personal symbol,"

"lesbian-like," "a body that can access anyone,"

"something like a performance gesture," "aggressive and

obsessive, but very weak," "a carnivore that kills the most

people," "a dance." As an artist, Yeonså imagines their stage as

a "place that summons newborn mosquitoes." Amongst their

performer-mosquitoes, they also included a "vegetarian" male

mosquito. Yeonså ‘queers' the queer, who attempt to

stand their ground, creating a place where clichés crumble. Since children are

unaware of the law of binaries, as they take in the world through queering,

shaking the fixation of selfhood—they resonate with

minorities, risk-takers, the non-ego or other names like that.

While

casting performers for the previous two live performances, Yeonså mentioned

that they tried to find out about their trauma or sexual preferences, one by

one. Heading straight towards the 'secret.' As if the apocalypse is near, or to

live amid despair–showing your

vulnerable card is a quick and aggressive way to connect with one another.

Because Yeonså cannot kill these midsummer mosquitoes, this must be the bond

formed among those who "slap their cheeks in vain." The wounded body

and the shamed body are therefore quite appropriate subjects for a performance.

Yeonså's works and performances will continue to be a catalyst to bring forth

secrets and pain that have been buried, forgotten, or unspeakable. That was the

case for me. I'm sure it'd be the same for you. Even Cathy Park Hong said,

"As far as I know, Koreans are among the most severely traumatized

people."

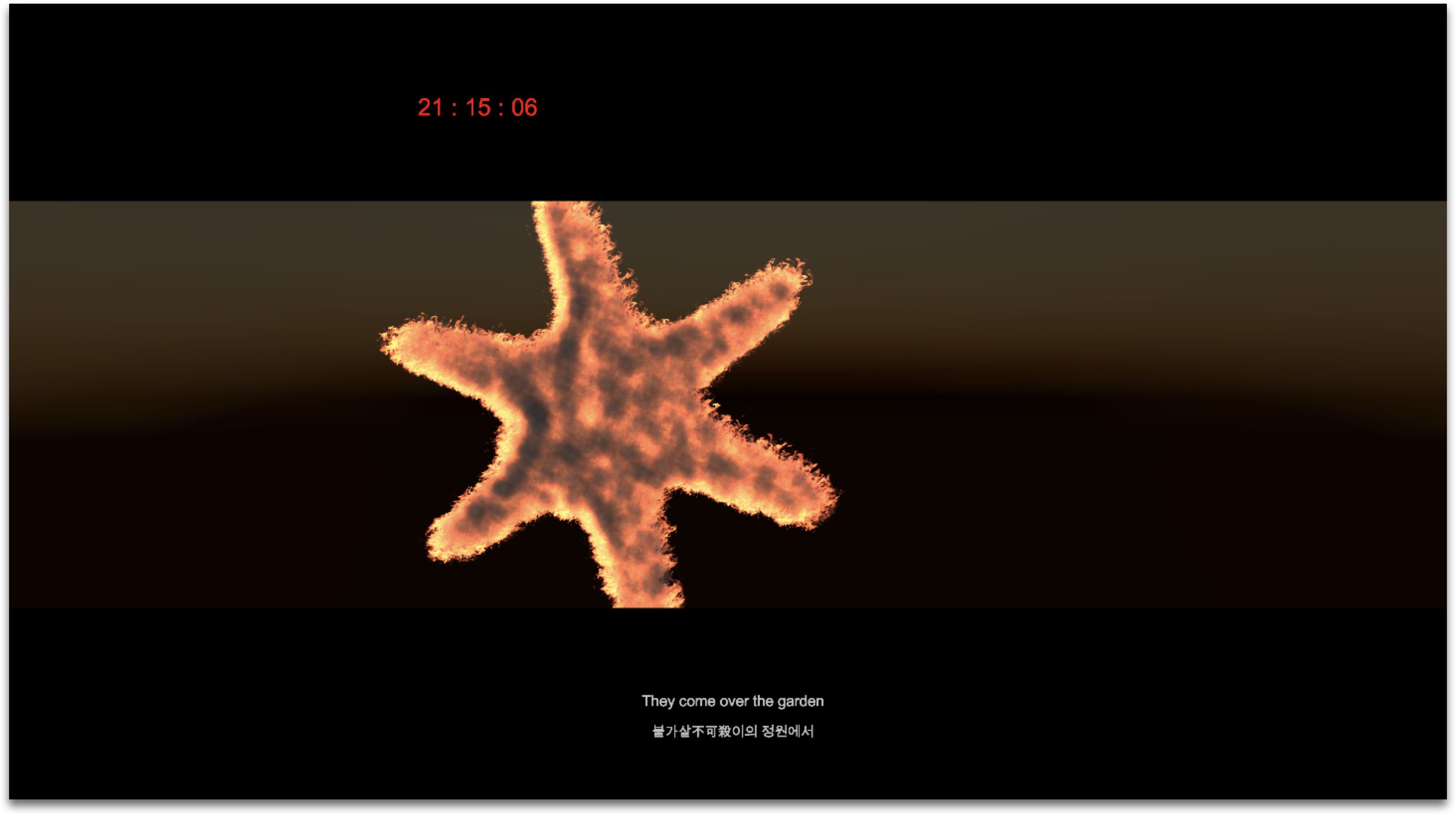

After

attending a poetry reading by poet Kim Eon Hee, Yeonså said it made them want

to live. Thinking of Eon Hee's voice, assertive yet jubilant, not yet dead but

aging, I could understand what Yeonså meant by that. Yeonså mentioned they

carried around poetry books like a "talisman." And this exhibition's

title, 《This Unbelievable Sleep》,

was derived from a poem called “One Day, One Morning (「여느

날, 여느 아침을」)”—a

poem that imagines waking up and looking down at your corpse one morning, a

morning when you needn't repeat the illusion, pain, and anger of living. A link

forms between Eon Hee and Yeonså, who both struggle with insomnia. In the form

of dead bugs in their papercut collage, Yeonså transcribed the phrase “heol, heol, heol (헐, 헐, 헐)”—the sound of

laughter from a hole spread wide in Eon Hee’s poem “At Dusk (「황혼이 질 때면」)”—in which the poet imagines her death with a playful rhythm.

For

someone inept in the language of games or computer-based videos like myself, I

find the ‘Festival’ series from this exhibition to be more readable and

approachable. Yeonså used elements from her late father, Cha Dongha’s studio, such as his belongings and bugs that they often encounter

there, as well as photos of corpses found in their girlfriend's book on

forensic medicine that are unbearable to look at—like

an abandoned baby still in the placenta, a man drowned in the river, a woman

starved to death, a woman who had been raped, the phrase "heol, heol, heol

(헐, 헐, 헐)" from the poem mentioned above.

Things

that are close and inescapable come forth to Yeonså, claiming themselves

through the forms of objects, images, the voice of poetry, and lives. Yeonså

describes their father as "someone who lived under all sorts of

rules." After their father's death, on behalf of the late artist, Yeonså

wrote a statement for an exhibition on his ‘Festival’ series. They wrote:

"A funeral flower carriage, abstracted through spectacular colors that

compose the joy and sorrow of life, accompanies the last road of the dead. A

festival of death and life." Flowers and funeral bier are culturally

close, and color is a ghostly veil that covers death.

Yeonså

appropriates the rainbow colors of Cha Dongha's funeral flower carriage as the

emblem of queer pride. By queering Cha Dongha, their own father who lived

within the boundaries of social norms, it is as if Yeonså is making him into a

soft bug or larva. Yeonså used their father's Mulberry paper (called Dak paper)

to transcribe the corpses from the book of forensic medicine–the bodily images of the dead that ordinary people are banned from

'seeing.' The visual forms of the Festival series, categorized as

"Papercut collage (colored on Dak paper, Cha Dongha)," finally

attained after countless failures of cutting paper with only scissors without

sketches or drawings, perhaps mimic the act of 'mourning'—something Yesonså didn't mention, a word for grown-ups.

Upon

close inspection, adversary places such as life and death, flower and corpse,

bug and human, corpse and form, which constitute the world of differentiation,

are actually one. Just like Yeonså's daddy and artist Cha Dongha are the same

person. Yeonså's works with an amoral gaze dismantled their father's allegoric

funeral flower-carriage, observing the corpses laying there—like "peering into the book to look at more terrible things,

because being alive is so terrible." But through a child's body, Yeonså takes

in that everything is connected—that two are in fact

one—and recognizes that the book they kept returning to

is no different from the literature of Sylvia Plath and Aglaja Veteranyi.

Perhaps this is why Yeonså refers to their cut corpses and the dead bodies that

finally stare back with their own 'eyes' as "friends." This is

evidence of a persistent, tenacious gaze that can only be reached through

analogy—and transcription is the only thing I can do.

With love, Yeonså's mother Sohn Nari, who translates and introduces the passion

plays of numerous artists, seems to quietly overwatch Yeonså's tribulation that

seems to pledge: "Rather than suffer like this, let's face the suffering

head on."

I

observe the photographic images and forms Yeonså transcribed onto paper with

care, which they felt was their “daddy's flesh.” Yeonså thought, "the

results seem as though bodies are having a festival in a funny-looking

shadow." Repetition creates difference. Difference takes the power away

from the 'original' and inserts a new force into the second. Yeonså's "festival"

differs from their father's—and this festival is a mild

laugh. Whether it be cannibalism, life itself, a neighborhood funeral carriage

passing by, art, or this-very-moment–a festival is not

losing the wavering laughter in the midst of tragedy.

And

I've run out of space to discuss other things like the collaboration with

photographer Hong Jiyoung, who also participated in this exhibition alongside

the previous performance. See you next time.