1. The Post-Life of Father/Painter Cha Dongha

The

last project that the Korean painter Cha Dongha (1966–2021) worked on during his lifetime was entitled ‘Festival’ (2006–2017). Using acrylic paints, he applied the obangsaek colors—the traditional Korean color spectrum of red, blue, white, black,

and yellow—to mulberry paper, before trimming down the

color fields to create something resembling monochrome painting. After creating

a few works in his ‘Festival’ series in 2017, he entered a hiatus lasting

around four years before his sudden death. Described as being “arranged with a unique sense of balance within grid forms bearing

clear monochrome colors,”

Cha’s

color field/monochrome paintings are elegant, serene, and beautiful. In an

interview, the artist said he hoped that his work would help in “consoling and healing people in the suffering we experience in life—offering peace of mind and healing of emotional pain simply through

the viewing of an image.” Cha Dongha—who would be roughly the same age as me today—created canvases of colors bearing cultural and regional

significance, based on a process in which he applied paints directly to Korean

hanji paper to form obangsaek fields and then used a knife to cut them down to

suit his desired compositions.

His style combined (practically invisible)

painting-as-act and the application of acrylic paint to a surface with the

(slightly visible) collage technique of layering color fields; the Festival

title served as a clue that introduced the cultural context (referent) of the

obangsaek colors. The culturally rooted image of the flowering colors becomes a

flowered bier or a banner for the funeral cortège that follows. The traditional

funeral that I witnessed as a child in my grandmother’s

neighborhood was a festival consisting of the family of the deceased;

professionals supervising the funeral rites; men bearing a coffin covered in

multicolored paper flowers; villagers holding similarly colorful funeral

streamers; and endless others following the procession. The individual’s death was signified as part of a ritual for the

community/collective to which they belonged.

For those who live on, the

spectacle of shared grief and mourning contextualizes death as part of the

collective/community and as something that can never be merely personal. We

live today in a culture from which death has been almost entirely concealed and

erased, existing as something unexpected or an object of fear. Yet within the

beauty of the symbols of death as mourned by a community and the flowered bier

passing through the heart of a village, there is a sense of continuity and

collectivity, showing that we will be preserved and carried on even after our

passing. Aesthetically structured in a way that avoids direct symbolism or the

sense of cultural affiliation, Cha Dongha’s festivals

of color fields, like his artistic process, seem to allude to his desire to

evoke such relationships, emotions, and promises in a kind of monologue (I’m not sure if the reporter understood his explanation above).

Cha

Yeonså may not have been fully aware of her father’s work—paintinglike creations that seem almost not to resemble paintings.

His death provided her with an opportunity/stage for observing his work as

someone who was herself approaching the artistic world through such

contemporary media as live performance, games, and cartoons. Cha Yeonså may

never have directly witnessed the traditions that the obangsaek mulberry paper

works denote/converge upon. Instead, she has experience with a different

community of brilliantly colored banners and costumes. In her feather’s “festivals” and

traditional Korean spectrum of colors, the younger Cha saw the rainbow hues of

queer pride. She shows no interest in a return/identification process in which

she learns from and establishes herself within her father’s culture and affiliations.

Instead, she has shown her prowess at

extracting the adult/male/mainstream/painter from within traditional

patriarchal culture and applying them to the culture of the non-mainstream

community to which she belongs. She insists that even for her father, there was

“definitely a queer aspect to his being a man who used

colors.” In that sense, the father Cha Dongha lives on

in a different post-life from the context of his painting work. As someone who

lives their life carrying, repressing, denying, and recognizing the not-me

aspects—the excess—we truly

resolve them through the self (me).

Cha Dongha’s

surviving works faintly referred to and latched onto cultural forms from a

tradition that had nearly died away; now, a certain excess—a remainder that both is and is not “me”—is revealed through the parallax perspective of Cha Yeonså as

someone who enjoys working in various peripheral/radical genres. What connects

the past and present festivals is the use of brilliant colors, creating both

similarity and difference as the superficial aspects render unstable the

biological relationship between father and daughter. This is both a

non-binary/queer person’s form of mourning for their

father and a subcultural transformation of traditional/mainstream culture.

Cha

Yeonså’s re-appropriation and reuse of her father’s work becomes something either inevitable or moral. The

time-honored/timeworn forms of death are “refreshed” by an artist who is more urgent and vital. Cha Dongha’s work Festival 09 #3 (2009, 103x180cm), which “clearly used colors representing the rainbow,” appears in the contemporary artist Cha Yeonså’s second solo exhibition as a keepsake, clue, difference, and

hostage.

2. Photographic Bodies in a Forensic Medicine Text and “Paper Cut Collage” as Technique

The

starting point for Cha Yeonså’s work in which

she used scissors to cut up her father’s “rainbow-colored” paper and “materials as things in between objects and artwork” came when she read through a forensic medicine text left behind by

a girlfriend who has “studied emergency medicine and

had a lot of experience removing dead bodies from a period working for the 119

[emergency] service.” A great many sheets of paper had

been left behind in the studio. (How strenuous a process could it have been to

arrange the paper on the canvas that Cha Dongha found it so difficult to move

on the next stage after that long period of hesitation prior to beginning his

work?

In that sense it must have been a truly difficult execution!) There were

stacks of mulberry sheets in different colors, and Cha Yeonså debated what to

do with them—how to “consume” them. For her to shift the strict adult/male/artist to the

periphery—the one who had used his ruler and knife to

cut up the paper and create geometric structures—she

would need to begin/intervene from the opposite side. Because of her

astonishing/disjunctive skill with applying fabric scissors to paper for the

first time in her life, her trimming of the mulberry sheets took place in a

state where any intervention of the head/hand was nearly impossible.

As a

hostage/tool of the scissors, the younger Cha had an amateurish/random

technique and excitement that ran counter to the normalcy/inertia of a father

who had based his work on calculation and contemplation. The technique of “paper cut collage” was shared by both father

and daughter, but there was also a large difference in that the former used a

knife, while the latter cuts with scissors. The difference was quite large

indeed: the obangsaek colors outside the coffin, covering a “meaningless” body with symbols of community

and the afterlife, and the non-bodies that the community rejects: the

pornographic objects used by doctors to identify the “cause” and things that are meaninglessness itself, unbearable to the

untrained eye.

The father painted the veil; the daughter actually ventured

straight inside. Cha Yeonså writes that she “looked

inside the book because being alive was so terrible, and I wanted to see more

terrible things.” The natural outcome (price) came as

she began applying her scissor skills to mulberry paper for the first time in

2023. The state of being conscious with paralyzed limbs—of having the consciousness separated from the body—ate away at a young, frail body that had seen what should not be

seen. This was the price exacted—and, as she must have

realized later, the gift granted—for passing the

threshold and sharing the use of a studio that had also been a small room in

their home, along with objects whose names, reasons for being, and affiliations

had faded away.

What Cha Yeonså received was a dead woman who had been

assaulted and raped, with a comb thrust into her genitals; a fully matured,

stillborn child discarded in a trash bin; pieces of flesh with all

representational aspects stripped away; hands and feet without wrists or

ankles. What the self saw became something that confronted, swept over, and ate

away at the self. Off in the study, mother Sohn Nari turned a blind eye, as the

house was left clammy with ghosts, phantoms, resentments, and sorrows that coexisted

with all-too-clear scenes/memories of a father’s

absence.

This was the artistic style and survival tactic of a girl/body

withstanding the awful fact that life went on even after the terror and grief

of her father’s death—yet

unable to follow or rely upon the social rituals for withstanding that. Cha

Yeonså rejected compliance with the binaries of adult society, with its demands

to restore day-to-day life in the wake of tragedy. She heightened tragedy into

tragedy, into an ordeal and persecution of self-imposed suffering.

This may

explain why the solo exhibition 《This Unbelievable

Sleep》—which Cha was set to hold after being selected

for OCI Young Creatives in 2023—never came to pass, due

to a set of complex circumstances. When she created her collage works in 2023,

they drifted placelessly and more or less namelessly, as she adopted the same

system that her father had used to title his series with names such as Festival

23 #1.

3. “Their Names” and Post-Life

The

names of the works in the ‘Festival’ series began appearing over the course of

the group exhibition 《Motel》, the Art Sonje Center group exhibition 《Tongue

of Rain》, and this latest exhibition entitled 《Feed me stones》. The title Bouquet

was given to the first work from the series in 2023, which shows a cut-out

image of a stillborn, fully matured child. Dildo was

assigned as a title to work #3-1 from 2023, showing only the lower body of a

dead woman found with a comb inserted inside her. Mandarava

was given to work #10, showing the lower body of a dead woman with her legs

spread wide.

Cha Yeonså’s series ‘Festival’ (2023–2024) represents a collaboration between her racing scissors and her

own right hand, which acts as a kind of level controlling them; the stories

placed after that title represent the horrors, hardships, and persecutions that

the artist has brought center stage, but the relationships between the results

and the names that she has assigned as a creator invoke the presence of a

child. Through her cutting, aspects of violence as representation and the

tactile qualities of “damp flesh” are stripped away almost completely, leaving something dominated by

the sense of play and of “seeming like.”

The stillborn child’s body with the

placenta attached resembles a bouquet held by a child; indeed, that is the

English title that has been assigned to the work. Cha’s

perspective shifts toward flowers and things that begin to look like flowers—toward a certain beauty or brightness that overshadows the tragedy

and “non-bodyness.” In the case

of the murdered woman found with a comb inserted inside her, the object is

replaced outright with a dildo—an object used for

sexual gratification.

The dead woman with her legs spread is given the name Mandarava,

based on the redness of the color field created with mulberry paper. In

Sanskrit, this word refers to the flower of heaven or to the devil’s trumpet; in Hinduism, it refers to a guru/deity. As a metonym for

the color red, Mandarava loses its cultural associations and stability through

its coupling with different signifiers; it becomes at once lighter, more

connected, and more distant.

Lingering

in a coffinlike room; withstanding bodies with uncovered coffins and deaths of

unclear causes (the hassles of the adult/male world); listening to their

stories of grief and anger, and thereby ex-isting as a “not-me”—the underdeveloped child completes

all these acts like homework lessons. Looking once again, she confronts the

deaths and stories she has translated to paper. “When I

looked at the results,” Chai said, “the bodies all seemed to be performing a festival in funny-looking

shadows.” No longer objects from a forensic medicine

text, they have gained shadows and engage in festivities, and thus they need a

definite name.

The difference/uniqueness of Cha Yeonså appears through the

force of the shears within the disjunctive relationship with paper, having

established a proficiency for improvisation and elusiveness; through the “freshness” of forms that gain new lives

through “mulberry paper like patches of my father’s flesh”; and through a realm of persecution

where there exists no other reason besides love. If a child that has been

stillborn and abandoned is a bouquet, if the comb inserted in the genitals of a

murdered woman is a dildo, and if another dead woman with her legs spread is a

Mandarava, then tragedy can be said to harbor a humor, brightness, and power

that is not reducible to tragedy.

This may be described as the complexity,

hybridity, and lightness of the world, which we bear witness to through the

mediating presence of Cha Yeonså—an artist who is

neither a shaman, strictly speaking, nor fully a child. Having first received Mandarava,

a work intended as a text value or as an abundant gift, I observed it at home

and thought that this woman, so tattered that she appeared as thin and light as

a piece of paper, seemed to be masturbating. So what was responsible for making

this slain body appear to be pleasuring itself—the

artist Cha Yeonså, the scissors, or the situation?

Seeing the words of the

creator that appear before me, stating that this woman as a “flower with thick hair” is rubbing heartily

at her clitoris, I sense that this is true for all the weights of the world. As

a result, the image at once resembles religious art, erotica, sculpture, and a

deadpan joke. The house is “lifted” by the red joke/play/laughter. Laughter is a spasm of the remaining

body that has been fully through the tragedy, surviving while remaining

faithful to the tragedy script.

Laughter is the haze or dust that arises in the

absurd situation of confronting of the self-evidentness of what is given. If

beautiful things are fated to be found out as horrible, then the place where

horrible things are found to be humorous is the threshold to life. Cha Yeonså

has been through that hardship and persecution.

4. Low Pressure Sodium Lamps and Monochrome Painting

The

term “monochromatic light”

refers to devices such as low pressure sodium lamps that are applied to limited

uses in outdoor environments such as highways, tunnels, low-visibility roads,

refrigerators, and other settings where difficulties distinguishing colors make

the use of ordinary lighting unsuitable and where color rendering (a property

of light sources that make the colors of an object appear distinct, with index

values closer to 100 indicating lights that are most similar to natural or

solar light) is not an issue.

Room for One Colour, a 1998

monochrome light installation work by Olafur Eliasson (with a target color in

between yellow and orange), overwhelmed the colors of the viewers’ clothing and shoes, which might have appeared “natural” from outside. This experience with

an interior where only the yellow/orange spectrum remained was described by a

critic who wrote, “The central element is the

realization that the external reality is conditioned in large part by our

perceptions of it. Through our understanding that vision is not inherently

objective, we are able to see ourselves and the outside world through different

colors/perspectives.” Cha Yeonså has explained that she

became aware of Eliasson’s strategy while preparing for

this solo exhibition at SAPY.

Cha

has introduced monochrome light to the gallery to mitigate a situation that she

experienced when all the different emotions she experienced as she began her

own ‘Festival’ series in 2023—as a relay

continuation of and intervention in her father’s series

of the same name—disappeared in the next year, leaving

only the practical functions and technique. (A major part of this had to do

with her adoption of an exceedingly vulnerable dog named “Teto,” who could barely see or hear.) The

artist had undermined normative prestige with her misreading of the obangsaek

spectrum as a “rainbow,” and in

her exhibition venue, those colors vanished performatively, losing all of their

cultural force.

Cha also made use of Olafur Eliasson’s

monochrome light as a convenient means of “connecting

myself with the dead bodies/phantoms/them.” In a gray

room designed more for a performance than an exhibition, her “they” are exhibited sprawling over the

floor. Like coffins, like “small, tender things” that one might easily fold, the works lie on mirror film that is

modeled on reflective water, causing the ground to shimmer and reflect the

viewer. The images are so blurry and blackened that one has to approach very

closely to see what they have been cut out of, while the original color of the “material” is completely unknowable.

The

gallery installation creating something resembling an underwater environment is

based on a pond outside Cha Dongha’s studio in

Namyangju. Cha Yeonså has described the sense of feeling persecuted in her

father’s studio—shunned there

by the items collected by him during his lifetime, the lovingly cultivated

trees and the insects that had grown up there. (Hearing and seeing to excess

represents both a hardship and a gift of the younger Cha.) She also mentions

having reconciled with the trees during a three-day stay to record sounds in

her father’s garden with the exhibition’s sound designer and sound director Lee Solyoub. Explaining that Lee’s “spiritual clarity” was a source of great help, she has said that staying the night

there evoked a sense of beauty that was the polar opposite of the setting’s aggressiveness. (Perhaps a setting where one can commune with

ghosts, phantoms, trees, and the frogs in the pond is itself a queer, tender,

vulnerable, open, and loving environment.)

A

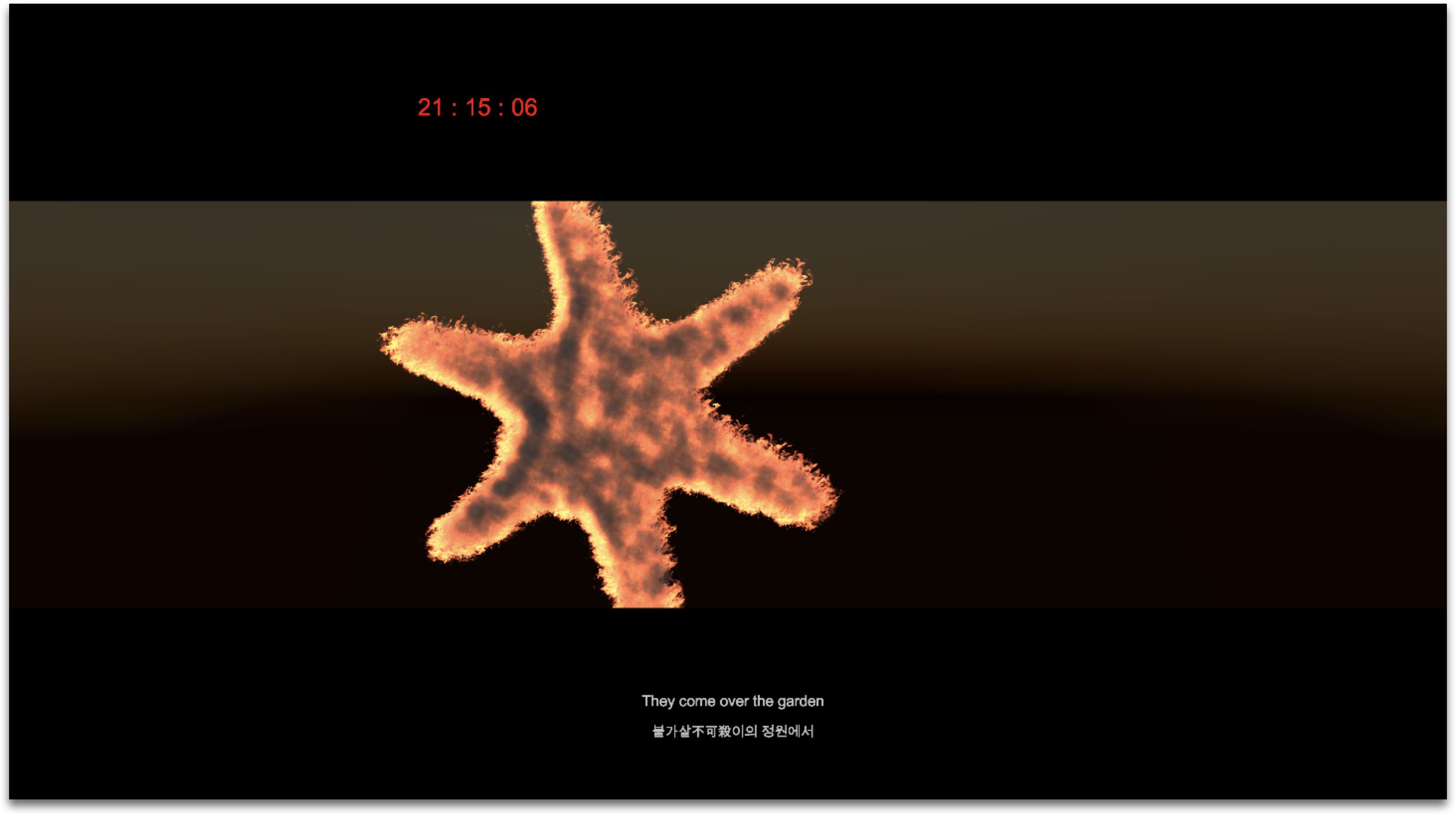

suryukjae performed by the Buddhist monk Donghwan—a “religious ritual of reciting the Buddha’s dharma and offering food to comfort and appease spirits and hungry

ghosts roaming the waters and land”—is followed by Lee

Solyoub’s mastering of the song “Ongdalsaem” and a monochrome video showing

Cha Dongha’s garden and pond. At this point, I grinned

broadly. Here was a long-forgotten children’s song, an

image of a deep valley pond providing a home to frogs—the

places associated with the dead father, now presented as non-human/living

things welcoming Cha Yeonså. The gallery was arranged/structured to resemble

the inside of a pond, and while the artworks (and their associated stories) may

be situated inside of that, so are we.

Through the monochrome light-based stage

installation, all the different presences invited into the exhibition “become gradually brighter through other means besides color—soaked, lifted, peeled.” Immersed in water

and summoned like spirits, we begin to “peel” like loosely pasted paper. “We” disappear, entering a pseudo-experience of something more akin to

the afterlife or a strange form of life. Donghwan conducts a ritual to bring an

end to Cha Yeonså’s “festival,” to her persecution, her odyssey. This somber ritual of deliverance

brings the artist to her next work, soothing her “them” and the non-human beings that exist under many other names.

It

operates as the work of scrubber-performers who cleanse grime that has been

swollen with water. At the same time, these are words that can only be spoken

by Cha as the one who has lived through all these experiences; the “unattended spirituals” and “festivals” are not mere recipients of the

artist’s beneficence and care. She knows all the things

that they have done for her. The same idea is expressed by Johanna Hedva as

someone who has lived with all manner of illnesses and ailments: the idea that

in caring for those who are suffering and weak, giving and receiving are one

and the same. In the same way, Cha Yeonså shares how she has “learned that nightmares and sleep paralysis demons can sometimes be

very welcome things.”

Nothing

in this world lives/appears with just one aspect or face. Things are the most

beautiful because they are the ugliest, the most adept at welcoming us because

they are the most aggressive, and the brightest because they represent the

deepest darkness. We await the next work received/assumed by the vulnerability

of Cha Yeonså(‘s body) as she alternates

between the two extremes.

Postscript:

I decided that I would/could not comment this time on the scattered works of

poetry found throughout the gallery by Kim Eonhee, someone whom Cha Yeonså

often quotes. I felt I should not address the world of adult/female/monsters

because it was not so much a pond as a mire. For this text, I would be joining

Cha in experiencing only the world of the girl and “kappa” (cited by the artist as the character

she most resembles).