When

stranded, one has a far higher chance of survival with someone rather than

alone. In this era of disease, we may find a path forward in the works of Oro

Minkyung exhibited last year.

AI,

autonomous driving, the so-called “Fourth Industrial Revolution.” Technology is

acclaimed as if a new dimension of innovation has arrived. Yet despite such

advancements, we find ourselves helpless in the face of a pandemic that even

modern medicine cannot easily manage. We are learning that illness is not an

abnormal deviation from a “normal state of health,” but something that could

suddenly happen today — to anyone.

Still, we do more than merely acknowledge

illness as a state: we distinguish patients, spread strange rumors, and deepen

fear. Fear turns into stigma, directed at certain groups. A futuristic

environment reminiscent of sci-fi films coexists with the absurdity of rumors

like “poison in wells” from the colonial era. With little to do beyond keeping

physical distance, our minds spiral: “What frequency was the ecosystem using to

warn us?” Eventually, a thought emerges — “If Youngin’s ‘life-saving gaze

research’ had not failed, would it have helped?” Even knowing Youngin is a

fictional character from the artwork, we feel so lost and powerless before

infectious disease that such speculation seems plausible.

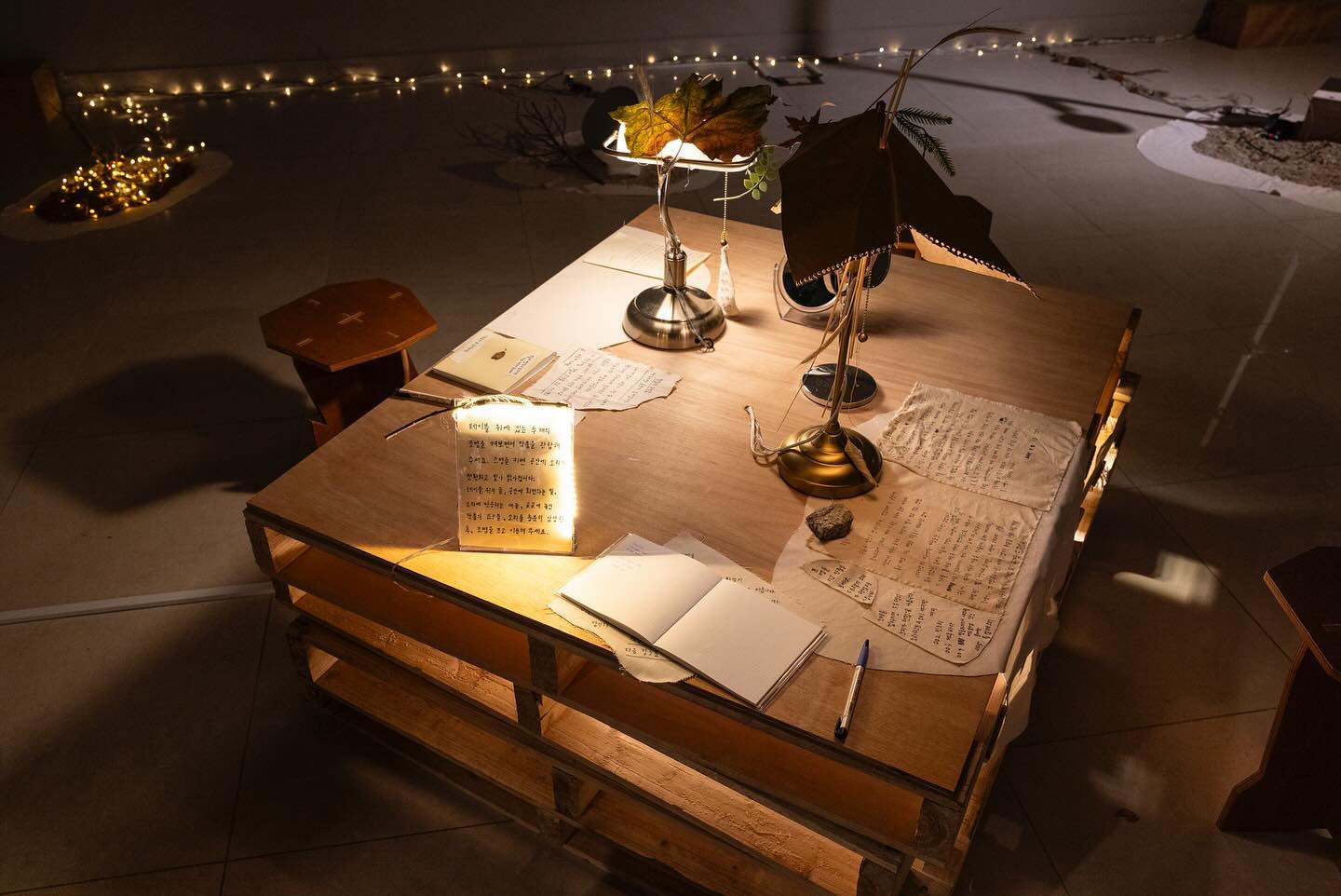

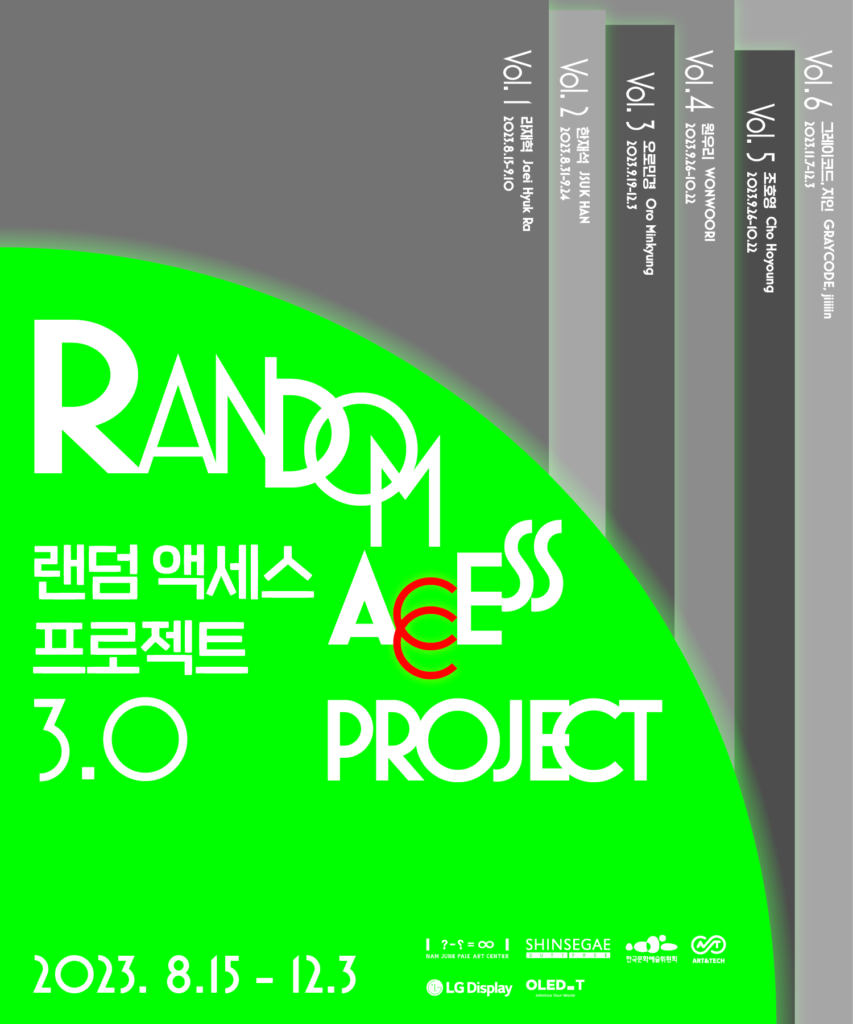

Oro

Minkyung’s solo exhibition 《Youngin and

Butterfly: Letters from the Particle Laboratory at the End》 (Factory2, Seoul, 2019) invited visitors into the laboratory of a

fictional scientist named Youngin. The exhibition space, transformed into a

research lab, displayed unfinished data, traces of contemplation, and

experimental results left behind as Youngin halted her research due to illness

— asking us through letters to continue her work.

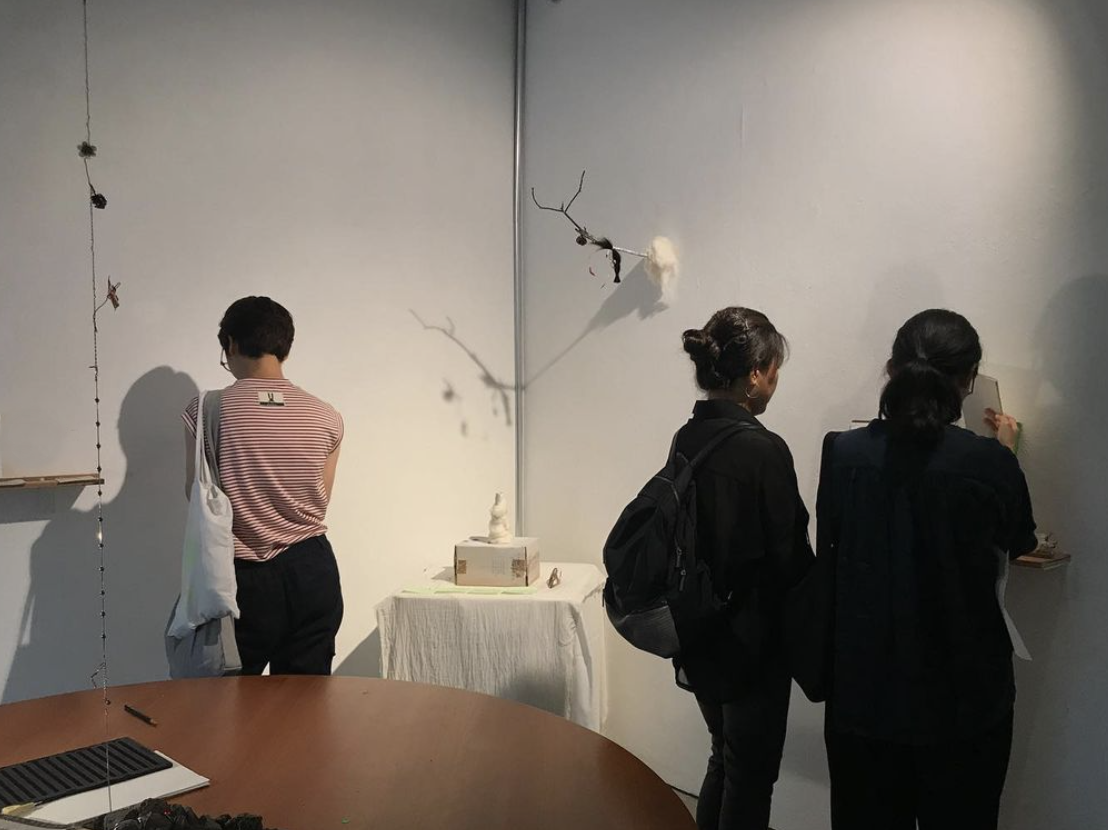

Various installations

described as “research outcomes” awakened delicate senses. Some works became

prisms, casting rainbow shimmer; pleasant scents emerged between laboratory

tools like Erlenmeyer flasks; warmth spread from a desk as subtle tremors and

faint sounds arose. Composed of fragile materials — light, shadow, sound, scent

— that seem to vanish at a touch, the atmosphere was not anxious but peaceful.

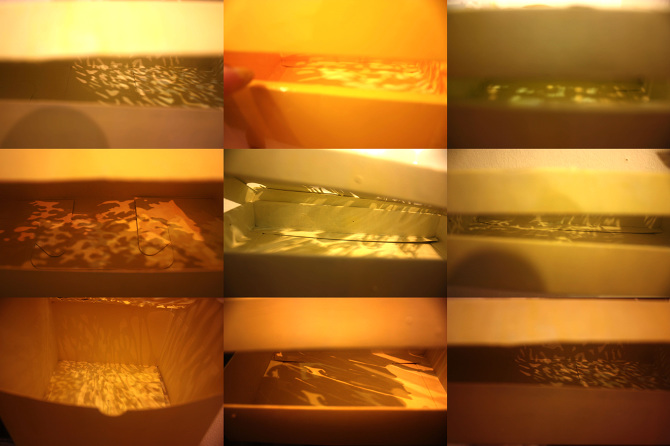

In

the installation of the “life-saving gaze research observation box,” I tried

hard to observe what was inside but failed. Thinking the experiment

unsuccessful, I turned my attention elsewhere — when a breeze brushed past. The

reassuring sensation in this space seemed to arise from a “connectedness” of

perception: when one sense meets a threshold, another quietly awakens.

Later,

I learned that the installation is structured so that when a viewer peers into

the observation box, the previously still installation outside begins to move —

yet the person looking inside cannot see those changes. Alone, no one can

activate all the mechanisms. Only with someone else’s participation does the

work expand its functions and amplify its narrative. Likewise, no one can fully

grasp the entire world at once. Thanks to another’s effort — someone observing

(something barely visible) — the beauty of this world continues turning, and we

get to witness its scenery.

The

laboratory became a stage for sharing experiences of other “Youngins”: not

disease as something to defeat, but illness as a state one passes through.

Here, people explored ways of walking together, rather than isolating those who

are unwell. Like a song too difficult to sing alone, but becoming harmony when

many voices join — a place for what the artist calls “the song of the turtle’s

pace.”

Before

condemning another culture’s “barbarism” of eating bats, we might first become

an observation box that turns its gaze toward our own culture that exploits

wildlife. Stigmatizing a group does not ensure safety. In a crisis, being with

someone gives better chances of survival: not only because it preserves body

temperature, prolonging life, but also because, as felt in Youngin’s

laboratory, the stability of being together can produce unexpected

miracles. When the world is dark and pathless, the stars — usually unseen —

shine more clearly.