Close

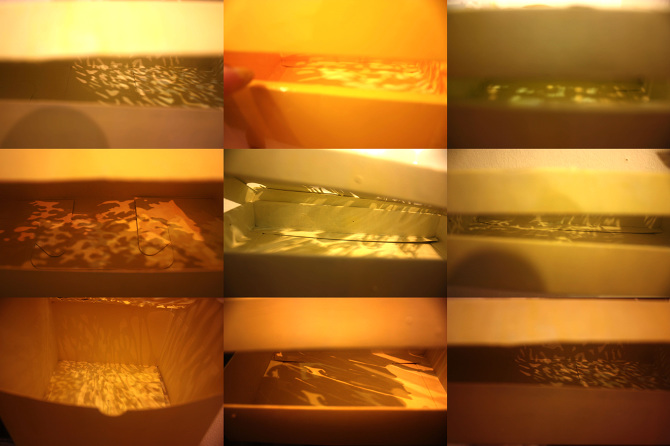

your eyes. A white room, dimly lit. The sunset lies low, and a beam of light

seeps through a small opening. The light reflects on something and scatters — a

mirror trick. Suddenly, memory rushes back to a faraway childhood moment: lying

sideways on the floor of a small room, rubbing the floor with a palm,

discovering a shard of light.

Playing with the light, bouncing it off a plastic

file, sending it across the desk, to the other corner of the room. Then — the

sudden discovery of a sound. The brassy honk of a car, the sound of footsteps.

A room once silent fills unexpectedly with sound. A space that had nothing now

overflows with light and sound, with something.

Bae

Minkyung(Oro Minkyung)’s exhibition pulls us back into that distant zone of

memory — awakening the senses we have forgotten, the ones we so easily pass by.

Memory gains vitality. Our senses begin to wriggle again. At the moment we

exclaim, “Ah, I’m alive!” the exhibition space becomes that tucked-away room of

childhood — the moments of ant-watching and mirror games…

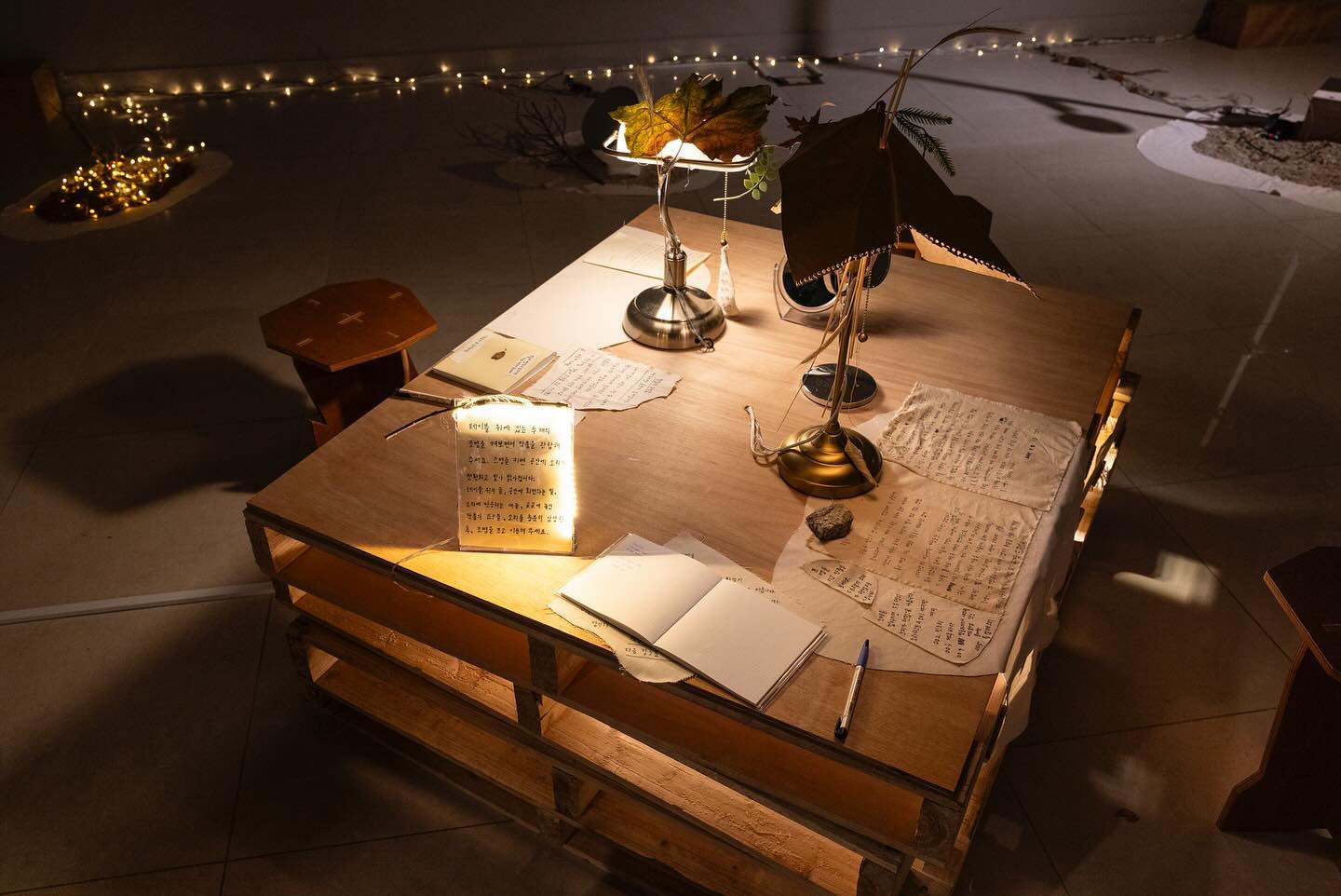

“The

floor is telling a story. Please remove your shoes… Walk gently. Rest

comfortably.”

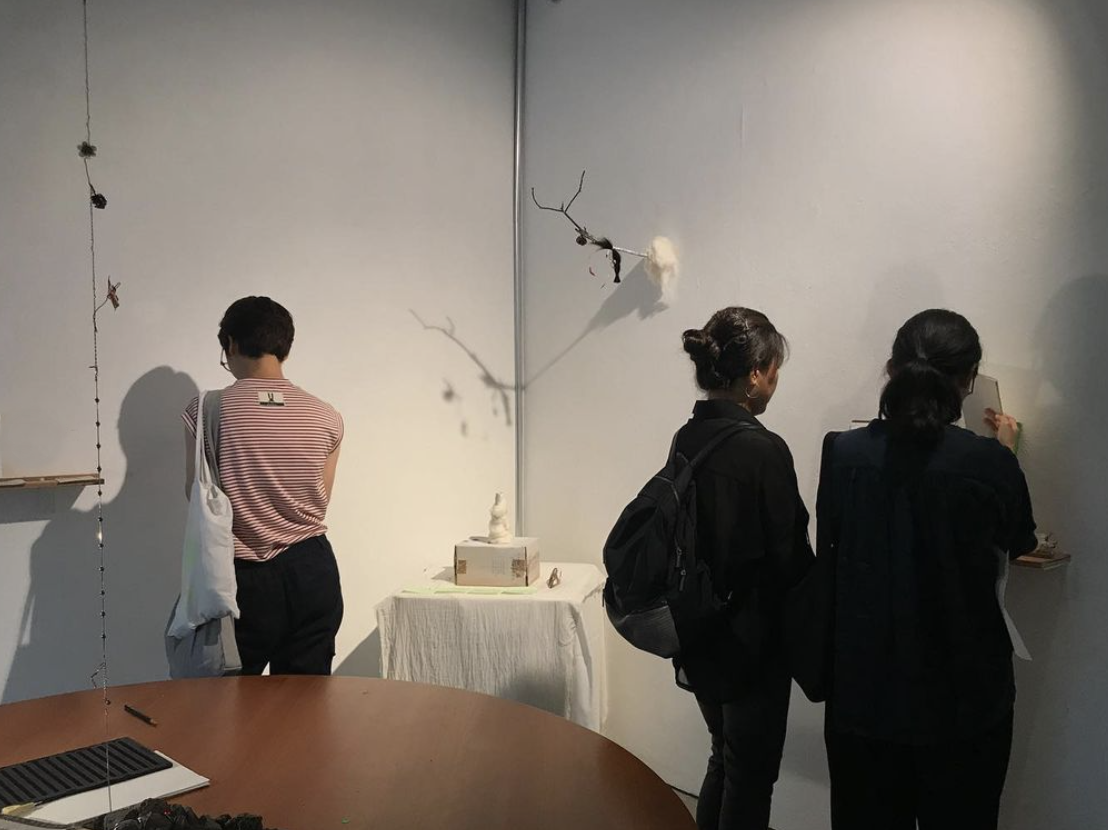

Entering

the gallery, like stepping into a room, we remove our shoes carefully. Soft

crackles greet us — rustling. Leafy aromas, the smell of grass, the quiet scent

of a forest embrace our body. Like children, we try stepping here and there. We

look into every corner. Creak, rustle, creak… Every step makes a sound. We

cannot walk fast. Softly, gingerly, the space makes us feel it. Then suddenly,

a thought: “Ah… it’s autumn. When was the last time I took an autumn walk? Was

I even breathing?”

Rustle,

rustle… the scent of grass, forest, fallen leaves — footsteps become sound, and

sound becomes fragrance. Further in, a soft buzzing hum… We listen closely — it

emerges from the floor. We lie down, carefully. It’s soft. Curious, we press an

ear to the floor. We enter the inner chamber of sound. Wind. Cars. Rain. Lying

there, a beam of light catches our eyes — streaming from the entrance. A mirror

reflects it across the room. Like Proust’s madeleine transporting us into the

memory of a far-off past, the exhibition draws viewers away from the present —

into the forgotten, blacked-out moments of our lives, into the sensory world we

have abandoned.

Listening

quietly, other sounds emerge — water flowing, pages turning, fingers typing.

And the young voice of the artist:

“We

constantly imitate nature. Yet no one can become nature. But still, we are

another kind of nature.”

Indeed

— her act is mimesis. The desire to resemble, to draw close to the subject —

nature. Through meticulous attention, she mimics nature, urban landscapes,

childhood games. Children’s play is grounded in resemblance: the ability to

imitate, to recognize likeness. Walter Benjamin once identified mimesis in

Proust’s involuntary memory; similarly, one finds in the artist

a childlike, playful impulse of imitation. She expresses light entering a

room, recollects childhood gestures, and reminds us of forgotten memories.

Through involuntary memory she recalls the past that had fallen into oblivion.

Observe

how she collects — fallen leaves, sounds, light — bringing them close.

Recording the sensory environment of urban parks, city streets, everyday places

in delicate detail, she resurrects experiences lost to indifference. In this

regard, she resembles a flâneur: wandering through the city with playful

curiosity, detached from productivity yet intimately engaged. She strolls among

hurried urban dwellers, chasing light and following fallen leaves; the intimacy

of resemblance births experience and restores memory.

“I

want to become the floor.

I want to become the underground.”

She

whispers her desire for attachment to her subjects — a mimesis toward nature

itself. Reviving experience, awakening what has been forgotten — through play,

she mimics this city and this society. Not by painting scenery symbolically

from afar, but by revealing minuscule details, she makes us perceive what

we have seen but never truly noticed. She captures rough yet raw elements —

recording the sounds of protests, gathering the water used to wash away the

past “with the heart of remembering.”

Rekindling

experiences on the verge of disappearance and summoning the past, as Benjamin

suggests, is not simply reproducing memory — it is perceiving

reality anew. Within the resonance of past and present lies

a dialectical image that can redeem the future. Through her innate

expressive talent and childlike sensitivity to resemblance, she awakens every

small and perceptible thing — not only the tiny experiences we overlook, but

our entire sensory world that must not be lost. In her collected voice, still youthful,

or in the landscapes she presents, one senses the promise of a more mature,

more refined mimesis yet to come.