“There

was a village where everyone had to close their eyes at birth. The villagers

were under the witch’s curse…”

That

was how stories by Noh Sangho (b. 1987) often began. They were shared

online alongside images painted with the clarity of watercolor. His delicately

arranged complementary colors harmonized with the narratives, and together the

texts and images spread like oral folklore through social media. Floating

across constantly updated feeds, some stories dissipated without an ending,

while others survived as fragments of scenes. Yet there was no need for

closure. Many people delighted in Noh’s daily uploads, and just when the

story’s conclusion seemed near, he would begin an entirely new one — as if to

remind us that this is how creativity circulates and dissolves in the

online realm.

The

opening sentence quoted above was also the title of his work exhibited at 《Young Korean Artists》 (National Museum

of Modern and Contemporary Art, 2014). The piece was installed inside a

“fairy-tale cart” fashioned from a discarded handcart once found near Hongdae.

In the dim interior, paintings depicting scenes from the story were displayed;

visitors could view only fragments of each scene by illuminating them with a

flashlight. Like overheard rumors or half-remembered songs, the work invited

each viewer to fill the narrative gaps with imagination. The more curious among

them would trace the story’s trail back to the artist’s online account.

#Art

After the Internet — Korea’s Post-Internet Generation

Internet-based

art first appeared in the mid-1990s under the name ‘Net Art’, referring to

artistic practices that utilized materials discovered online. Its essence lay

in the fact that the result was not mere imitation and that its originality

remained beyond dispute. Later, New York–based artist Marisa Olson (b.

1979) introduced the terms ‘Art after the Internet’ (2006)

and ‘Post-Internet Art’ (2008) to describe a broader range of

contemporary art grounded in online culture. Among its defining

voices, Artie Vierkant (b. 1987) explained that Post-Internet Art

occupies “a space between new media art, which emphasizes the materiality of

technological media, and conceptual art, which privileges immaterial ideas”

(2010).

In

Korea, attention to this “Post-Internet generation” began in the mid-2010s,

often referring to artists born in the 1980s. They were also central figures in

the “new alternative spaces” (sin-saeng gonggan) movement —

self-organized exhibition venues founded and operated by young artists. While

sharing a lineage with the earlier alternative spaces of the 1990s

that existed outside institutional systems, these new spaces distinguished

themselves by their focus on online activity. Their physical locations were

often tucked away in underused urban corners, accessible only through

smartphone maps, while their real sense of community and solidarity was

cultivated through social media networks.

What

makes this generation’s art distinctive is their dual experience of both analog

and digital environments. They learned about the world through printed books as

children, grew up with the spread of the internet in their teens, and came of

age with smartphones in their hands. Though trained in traditional techniques

such as painting, sculpture, and printmaking at art schools in Korea, they

simultaneously absorbed global artistic trends through online channels,

exploring new modes of expression. This generation is as nostalgic for analog

media as it is fluent in digital tools — and Noh Sangho is among them.

#The

Digital Nomad from the Analog World – Noh Sangho’s Hybrid Painting

The

works Noh Sangho presented serially online were titled ‘Daily Fiction’

(2011–). What began as a daily habit of drawing one A4-sized image has grown into a vast

ongoing series numbering in the thousands. His subject matter never runs dry,

for his source material is the endless flow of information adrift on the

internet — fleeting news, low-resolution photographs, and ownerless stories

that appear and vanish.

Noh’s

paintings are hybrid canvases that travel between the digital and

analog worlds. Each work begins with the artist printing randomly collected digital images and

tracing them onto paper with carbon paper. Through the process of drawing, the

original images are reassembled into entirely new compositions. The completed

works are then scanned or photographed and re-uploaded online — digital

information reinterpreted by hand, transformed once again into digital form. In

other words, it is an artistic stance that employs digital tools yet refuses to

abandon the gestures of the hand. Noh is a digital nomad who still walks on

analog ground, translating the volatile nature of virtual space into a

physical, embodied experience.

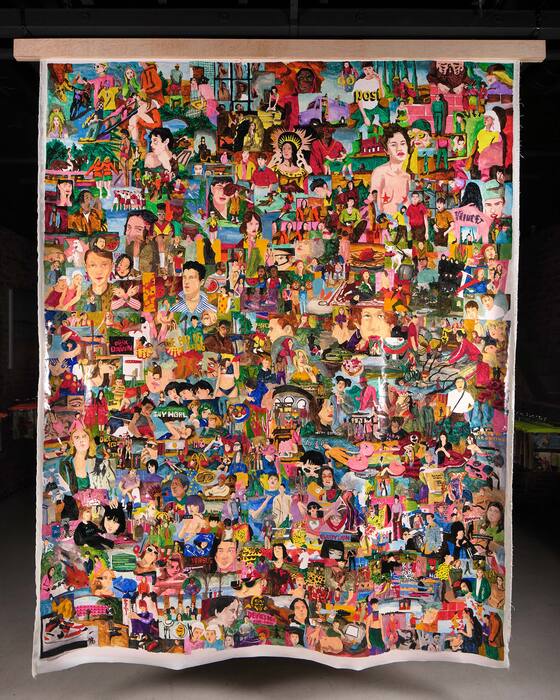

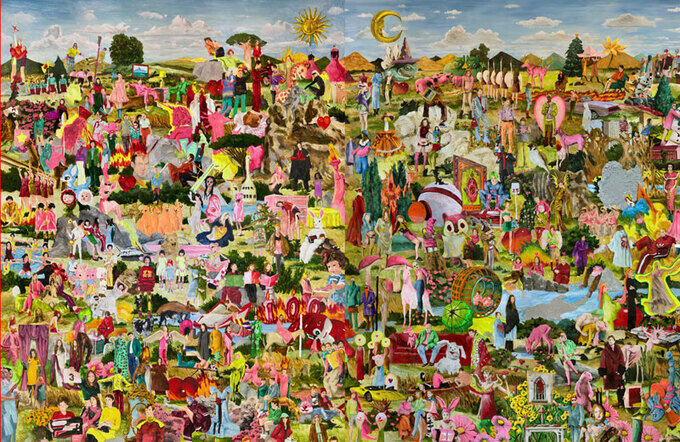

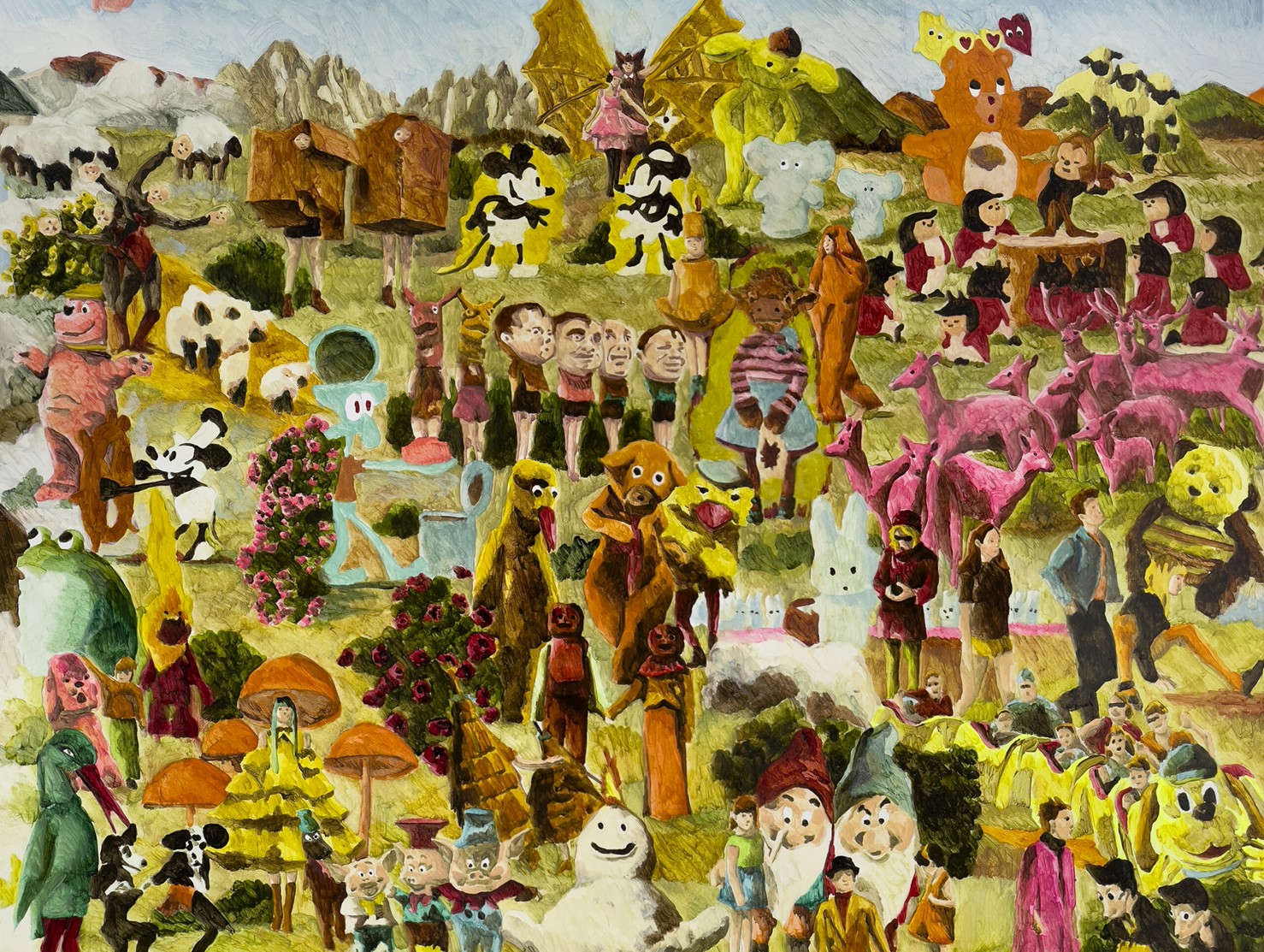

Daily

Fiction later evolved into a series of oil paintings titled ‘The

Great Chapbook’ (2016–). In these large-scale canvases, he densely arranges

countless images to form vast visual worlds reminiscent of digital clouds

brimming with data. The compositions evoke the overwhelming accumulation of

digital files, each image a fragment of a larger network.

After his solo exhibition of the same title that year, Noh stopped creating

stories in written form. Instead, he began to focus on exploring the ways

contemporary society consumes and interprets images — the very essence of his

practice.

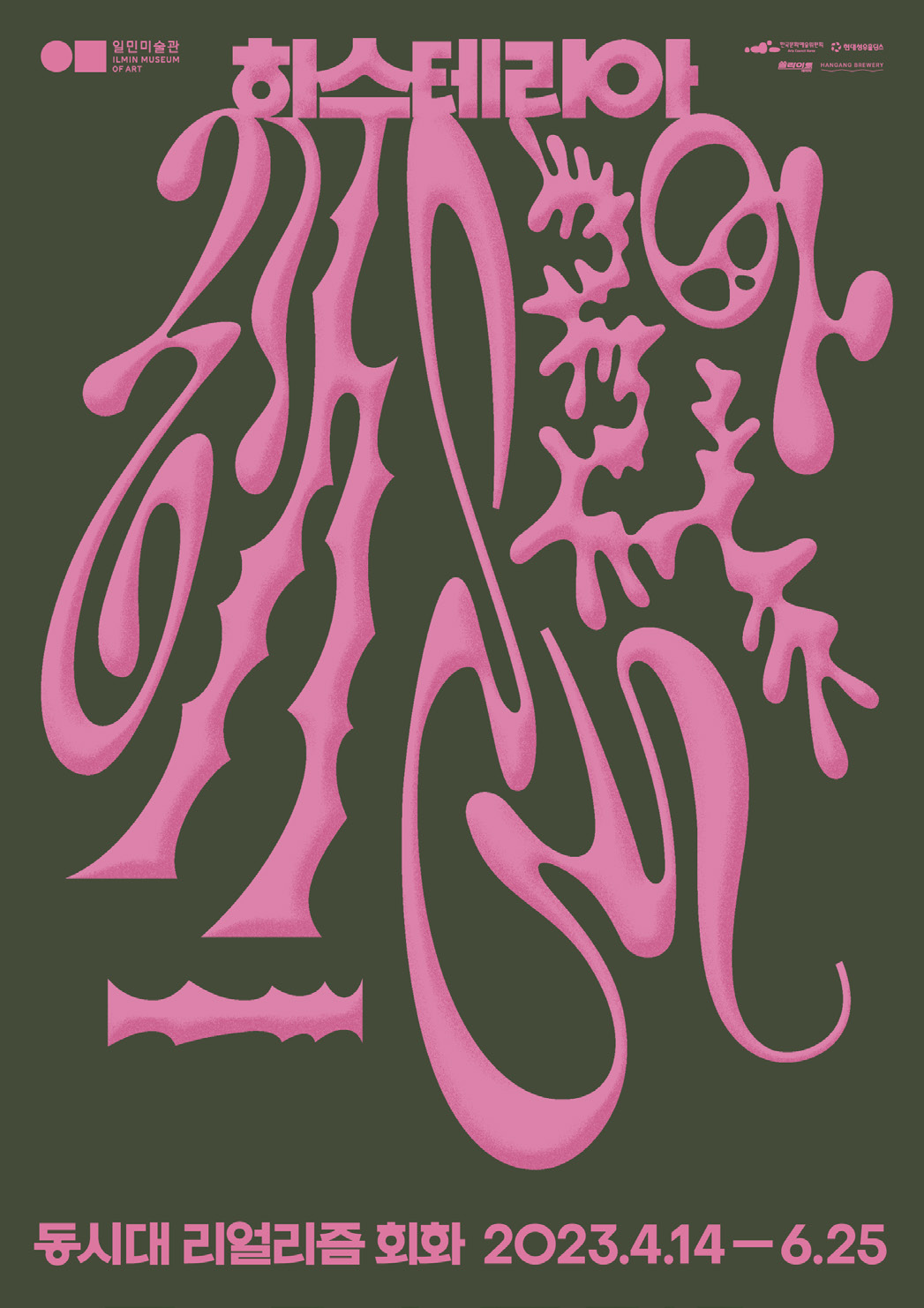

#Sacred

Images Beyond Grasp – ‘Holy’

Noh

Sangho’s recent works are featured in the group exhibition 《Romantic Irony》, on view from February 1

at ARARIO Gallery Seoul. This is the institution’s inaugural exhibition

after relocating from Sogyeok-dong to Wonsŏ-dong. The works are all titled The

Great Chapbook 4 – Holy (2023).

The

artist imagined himself as a kind of medium — one who translates the ghosts of

the virtual world into the language of reality. He recalled the miraculous

events that seem to occur at the boundary between these two realms: digital

images generated through technical errors, and the accidental traces formed by

the hand. To give material form to the immaterial is, for Noh, akin to the

yearning of believers pursuing mysterious faith.

The

virtual aspires to become real, while reality sanctifies the virtual. As the digital world grows increasingly tactile, the physical world struggles

to maintain the smooth, flawless surfaces of the virtual. Noh has recently

turned to the airbrush, a tool that sprays pigment rather than applying it

with a brush, allowing him to hide the marks of the hand and achieve a sleek,

digital-like surface. Conversely, he sometimes layers heavy materials such as

special pigments and plaster to emphasize the tactile materiality of painting —

in deliberate contrast to the smoothness of screens.

The

largest work in the exhibition comprises two canvases placed side by side,

their surfaces filled with a profusion of diverse motifs. At the junction

between panels, slight misalignments create visual dissonance. As the artist

sought to expand the scale of his paintings while maintaining the daily rhythm

of his Daily Fiction practice, he divided each canvas into multiple

sections, devoting a single day to each. The result was a natural time lag —

shifts in expression, changes in thought — and Noh intentionally preserved

these differences by refusing to connect the seams seamlessly.

One

painting depicts a house with wide-open eyes, its imagery layered from

overlapping scenes of suburban streets and portrait photographs found online.

In the process of merging unrelated images, Noh’s subjective imagination

intervenes. In the lower-left corner, pink heart-shaped motifs are scattered

like fallen leaves — figures generated by artificial intelligence.

Specifically, they were digital forms produced by inputting a text prompt into

an AI program, which the artist then reproduced by hand. Another work features

a rabbit created in collaboration with AI, reflecting Noh’s personal way of

engaging with questions about authorship in the digital age.

Smoke

rising from a chimney wavers like a dazzling inflatable balloon once common in

street advertisements. Those dancing balloons, once ubiquitous, now feel

strangely nostalgic. Today’s advertisements generate greater profit through

YouTube channels, Instagram feeds, and the folds of online news articles —

leaving little reason for such balloons to dance anymore. Yet, it’s hard to

miss them. The world simply changes, as it always has.

Standing

at the threshold of the virtual-reality era, we seem as hesitant as we are full

of desire — as we have always been when facing the mysterious. Noh Sangho’s

paintings tell us: This is already the world we live in. And perhaps, they

gently whisper — So let us drift through it with all the strength we have.