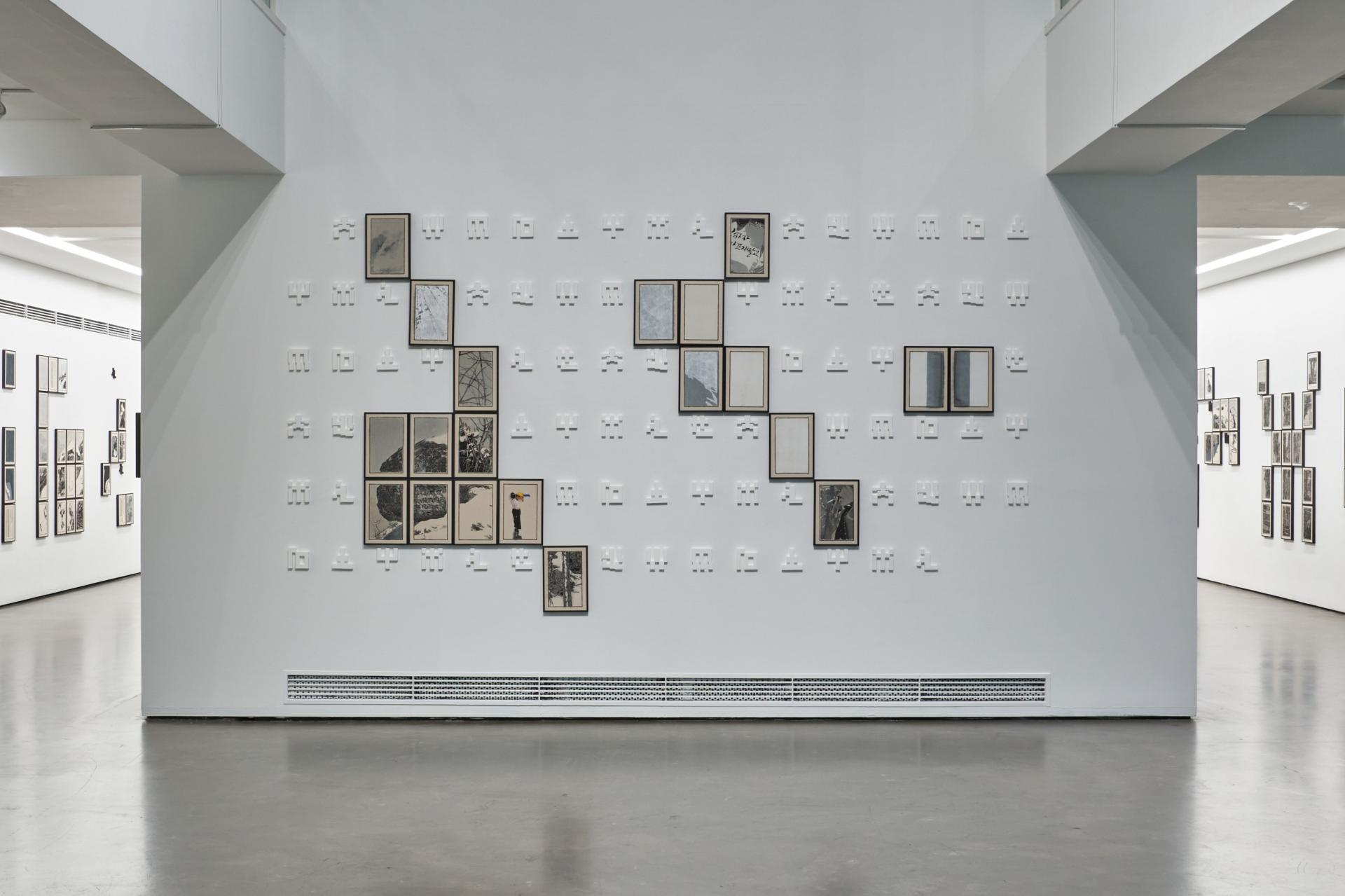

Hwang’s

formal experimentation focuses on transforming the language of traditional ink

painting into a mechanical and structural system. In 《Muh Emdap Inam Mo》, he combined painting,

printmaking, and relief sculpture to realize a form of “tactile appreciation.”

Designed for viewers to touch stone monuments and experience the layered

passage of time through touch, the exhibition expanded painting beyond its flat

surface into a sensorial field.

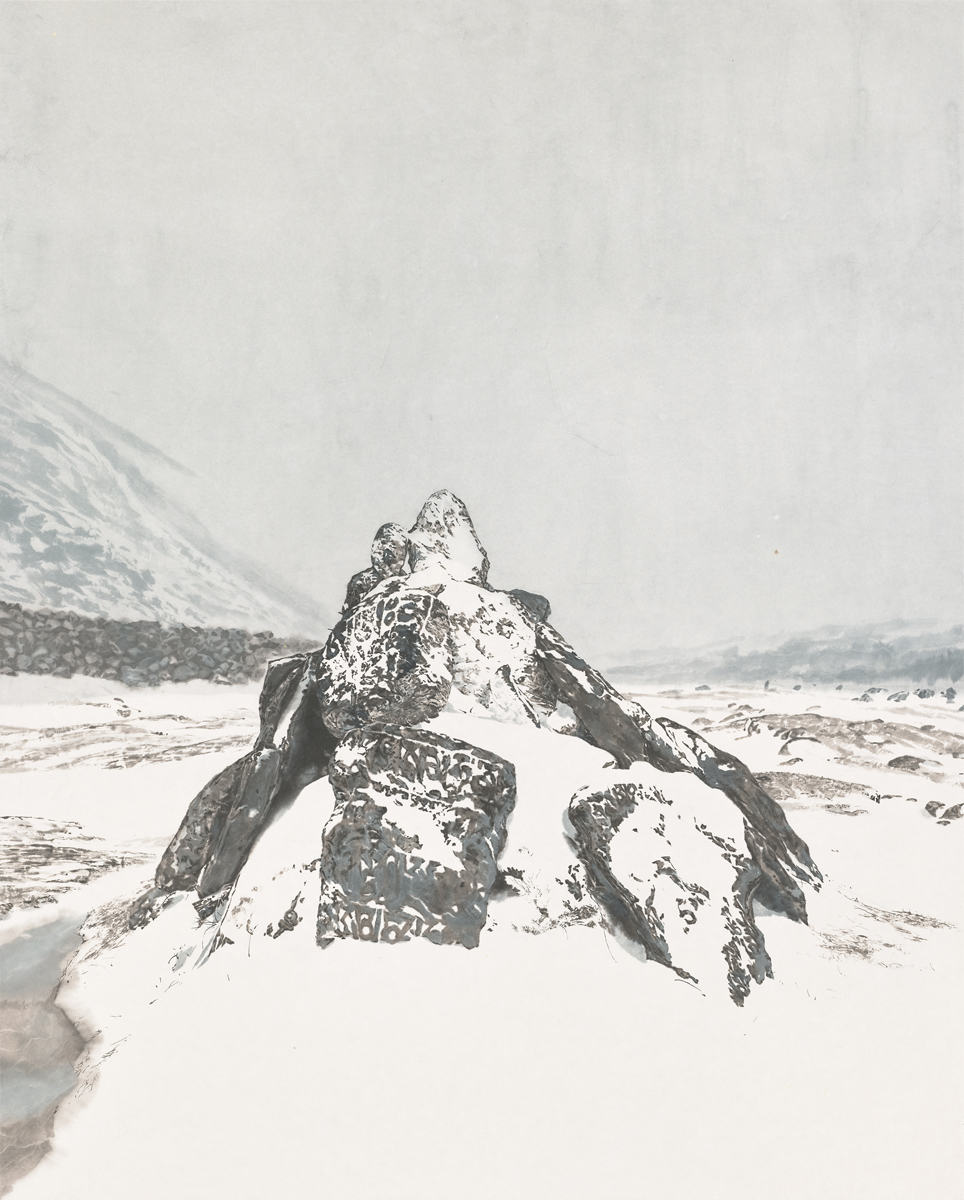

In 《Penetrating Stone》, he explored the balance

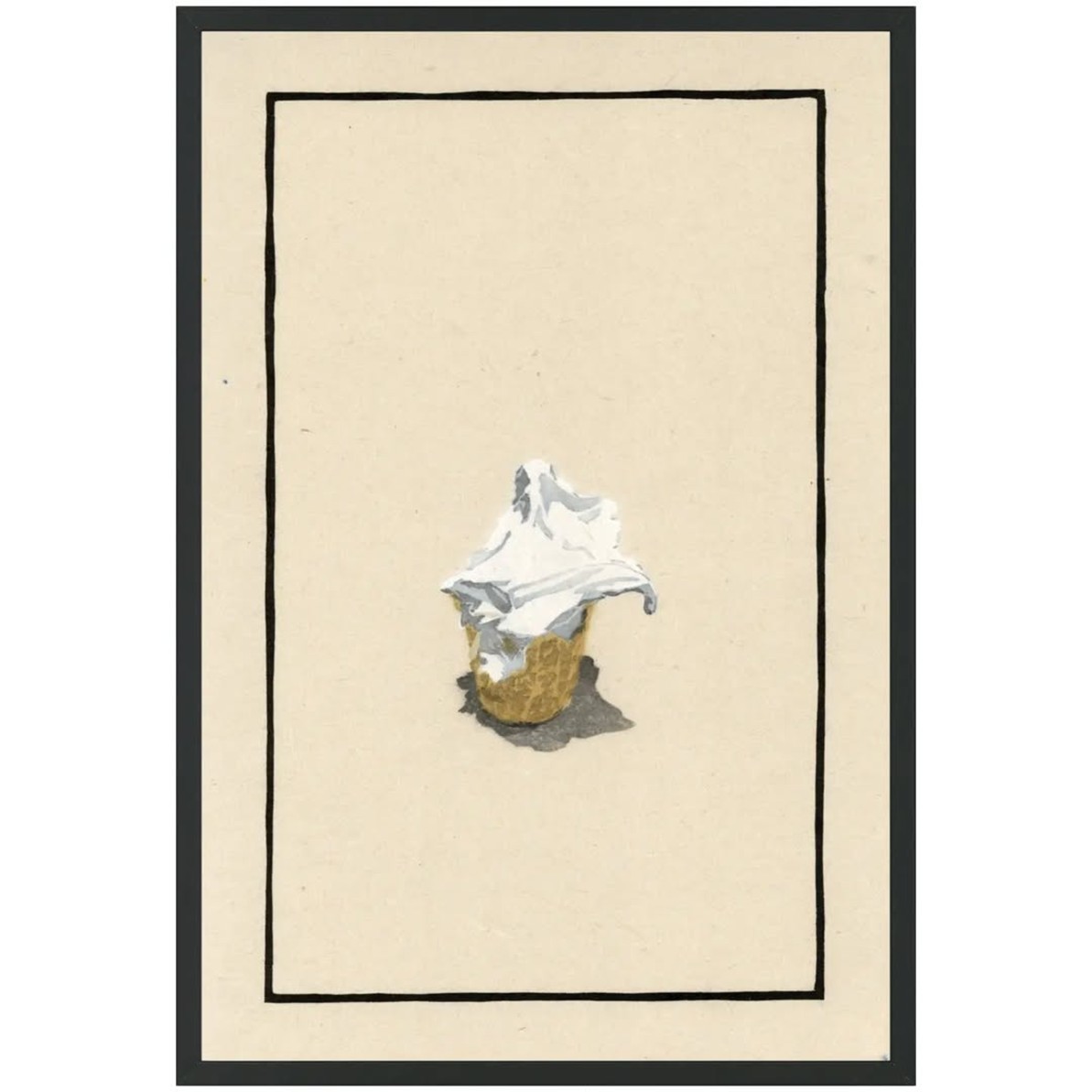

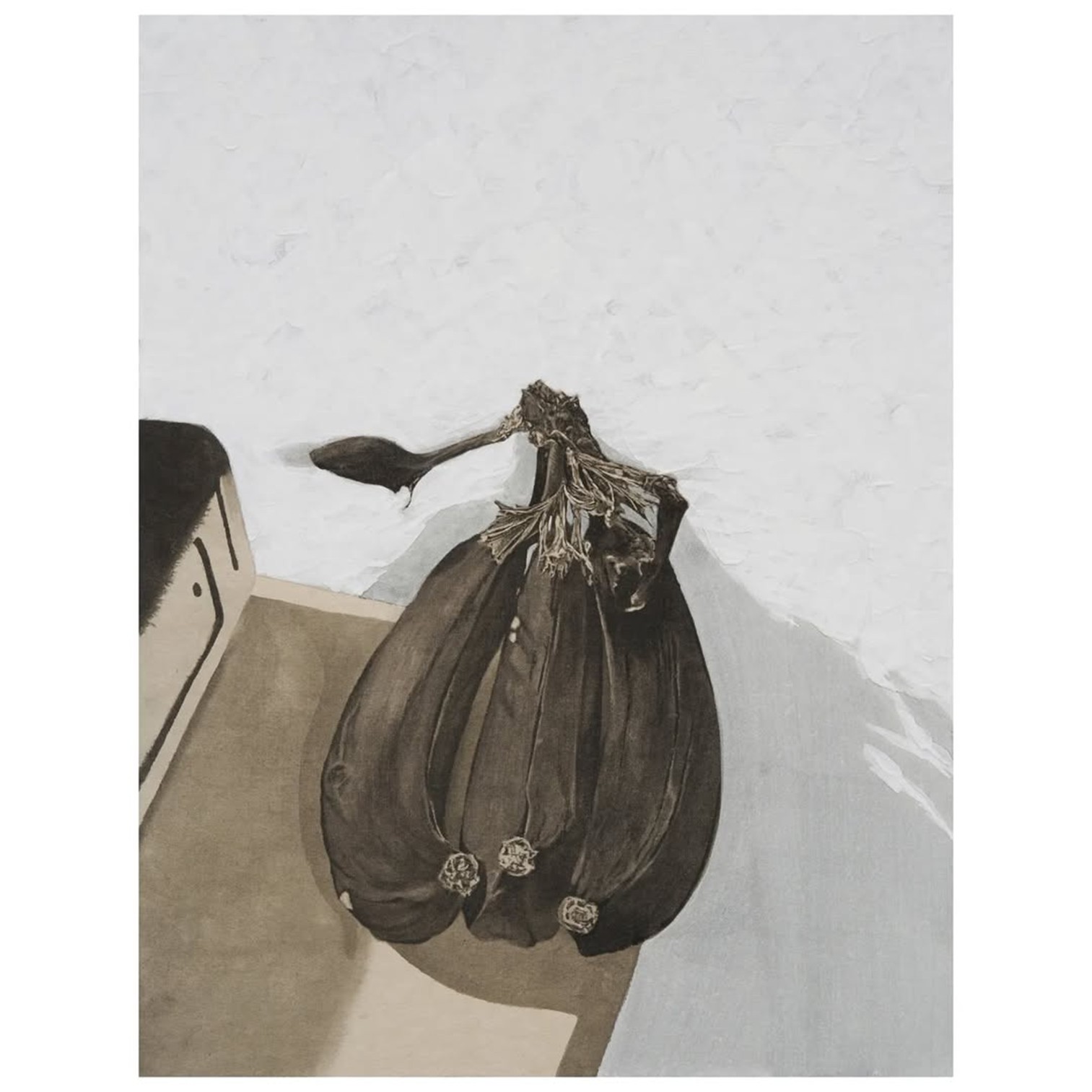

between the materiality of ink and the “photographic image.” The first series

translated snapshots from daily life into ink paintings, while the second

appropriated the format of the Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden

(芥子園畵譜) to reinterpret contemporary

scenes within a classical composition. The third series employed ink powder

produced by a custom-made machine to replicate the second series, visualizing

the intersection between traditional manual practice and mechanical repetition.

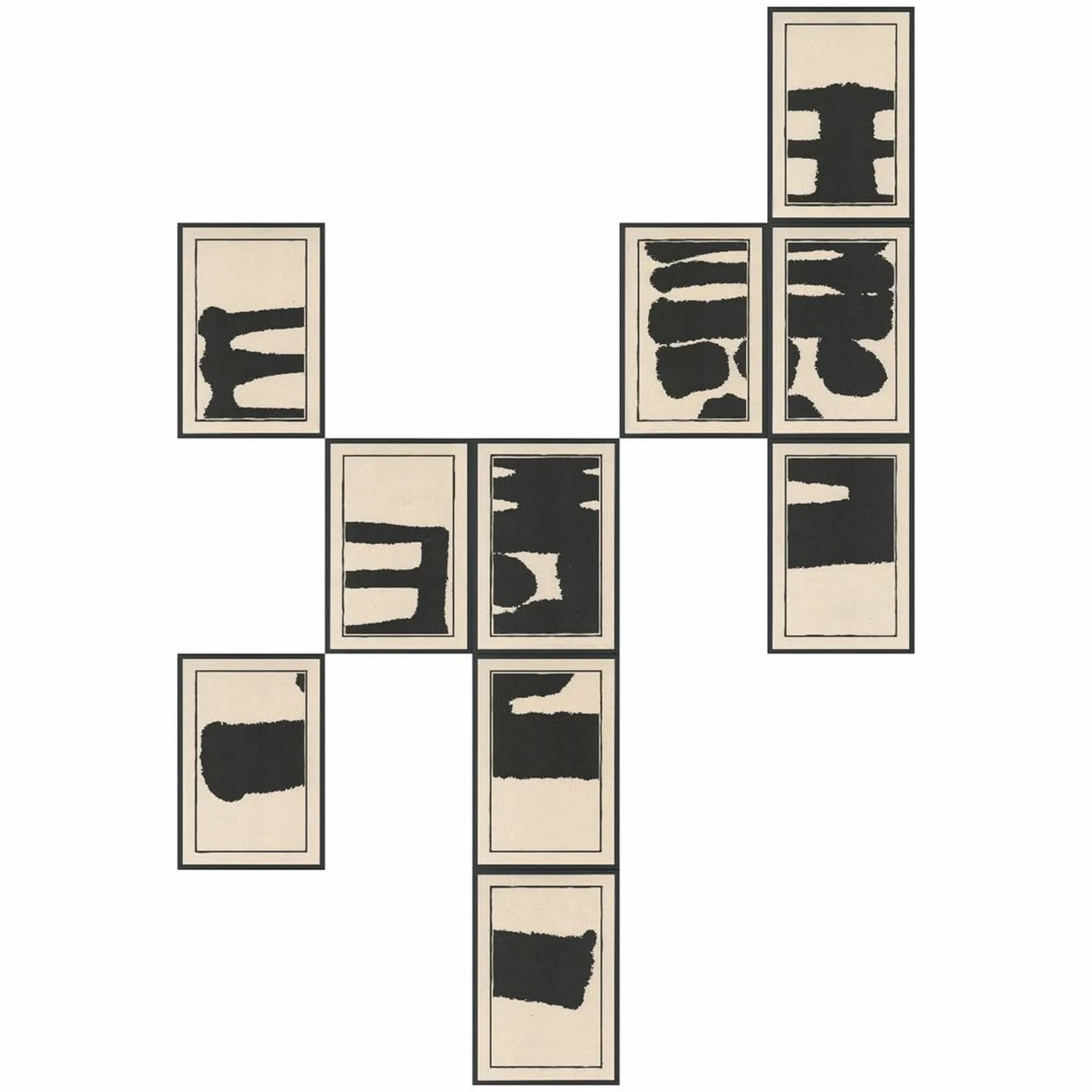

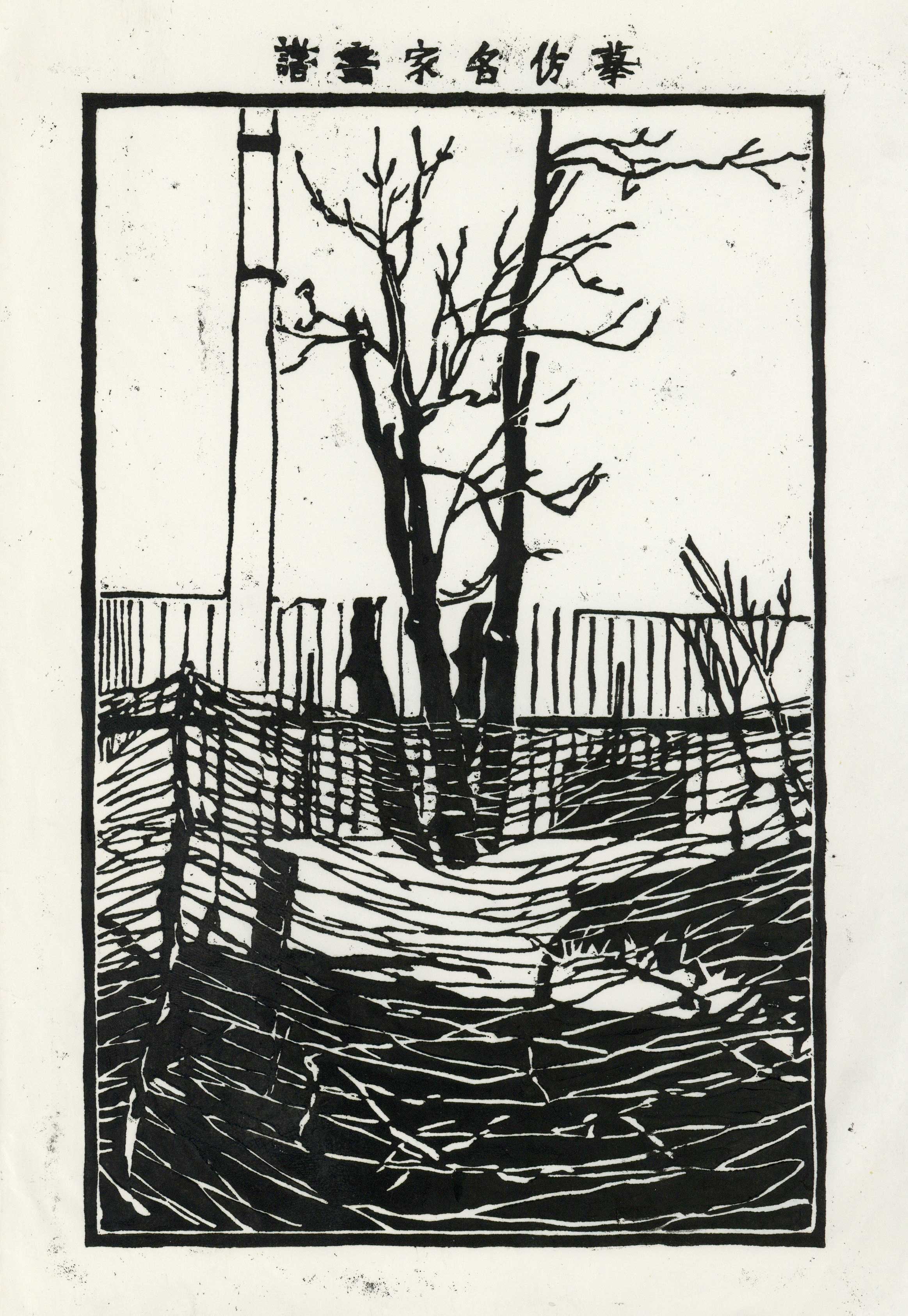

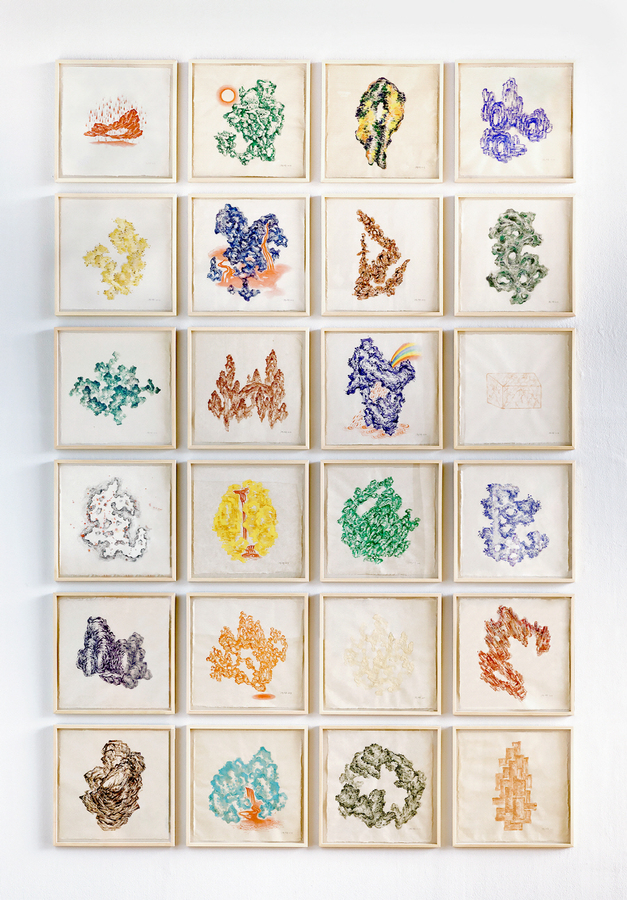

By 2022,

in 《Hwang’s Manual of Eternal Classics》, Hwang further systematized the structure of repetition and

appropriation. While emulating the compositional design of traditional painting

manuals, he reorganized his framework into ten thematic categories: Heaven (天), Water (水), Fire (火), Rain (雨), Stone (石), Earth (土), Grass (艸), Tree (木), Human (人), and Calligraphy & Painting (書畵). Each

category weaves together nature, humanity, and art into a unified narrative,

demonstrating that the language of traditional media can be reconfigured

through contemporary memory and perception.

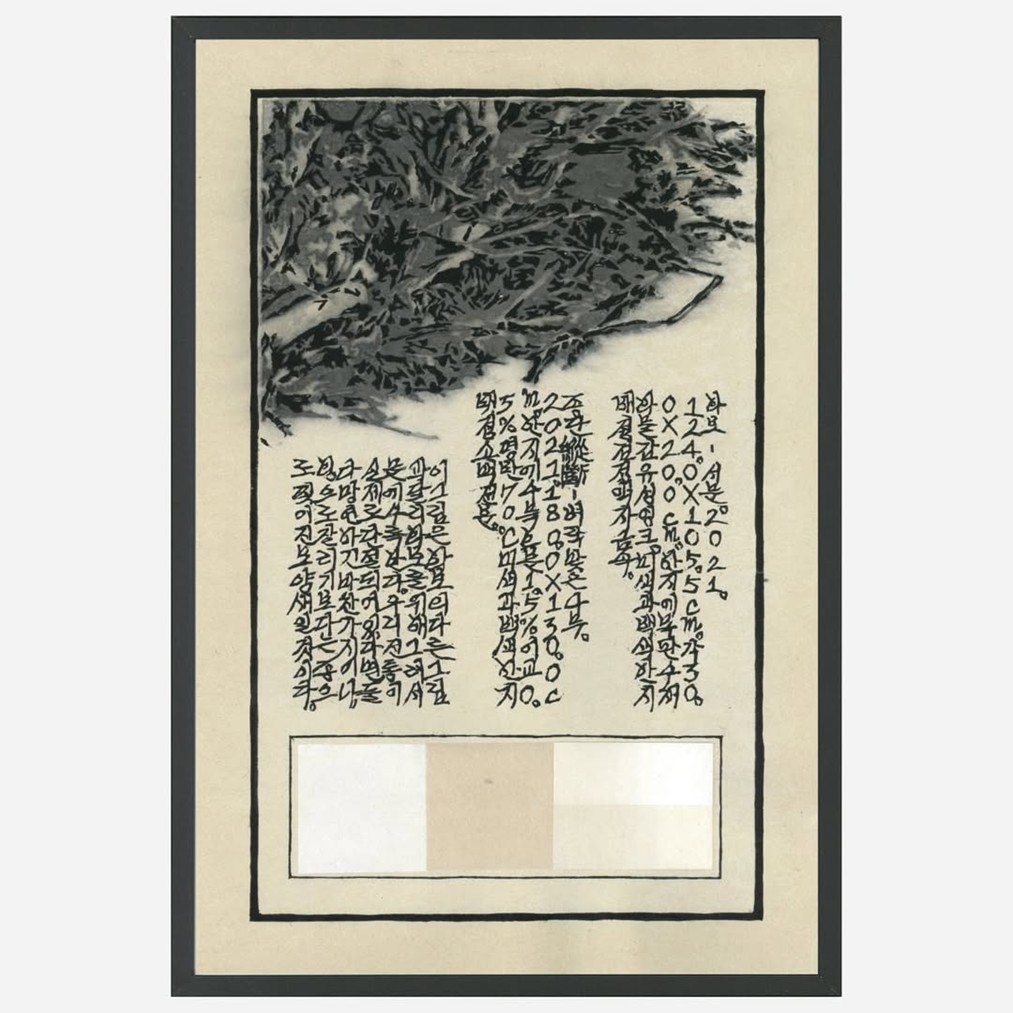

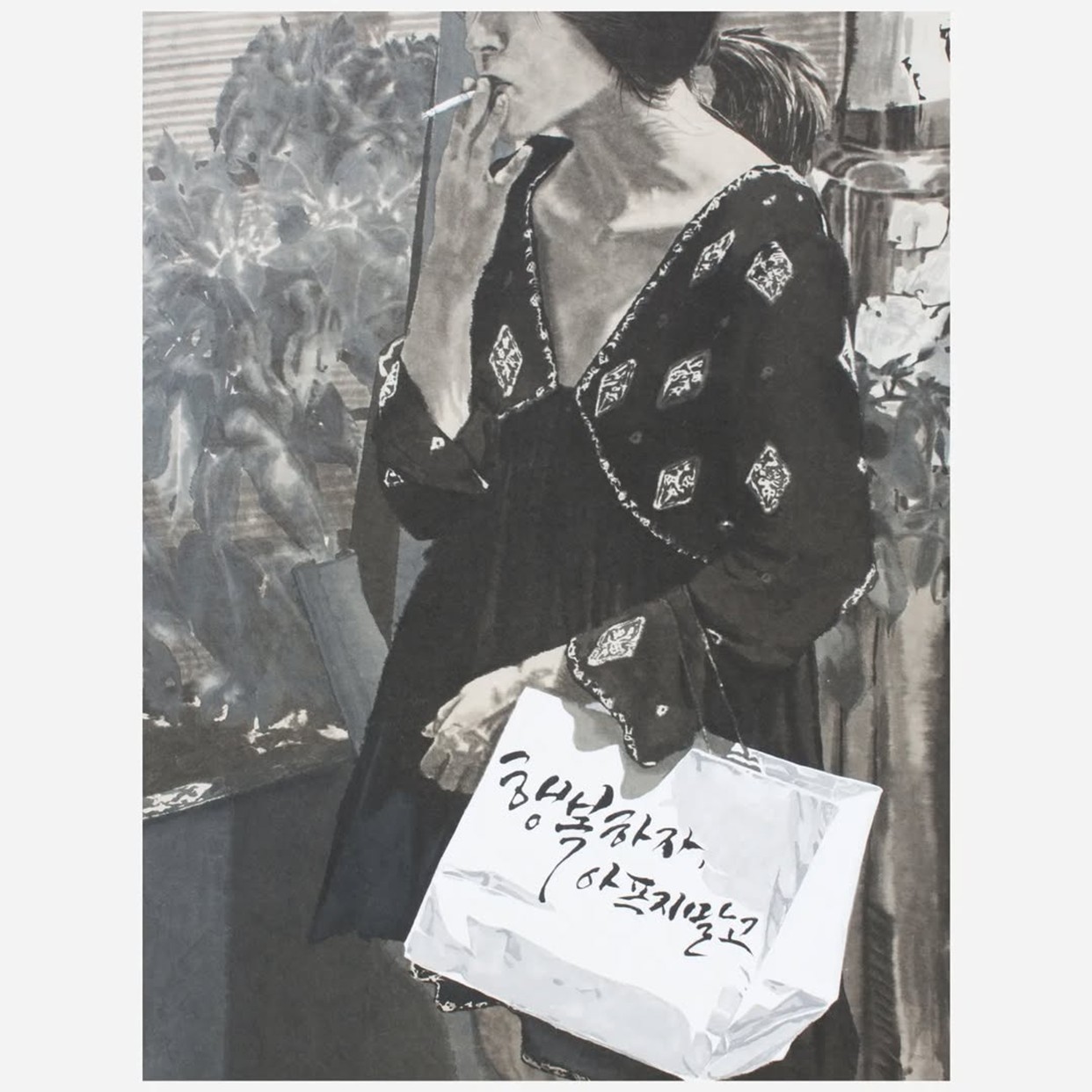

In 《Hwang’s Manual of Song’s Work – Throwing Arrows》, this structure expanded to incorporate the work of another artist.

Hwang recontextualized contemporary calligraphy and painting artist Jean Song’s

works, such as The Flower Arrangement by the

Shepherd(2023) and Hybrid Dove(2023), within

his manual system, producing a secondary pictorial structure exemplified

by Hwang’s Manual Painting – Hybrid Hybrid Dove(2023).

Through this process, the “manual” becomes not merely a record but a generative

device of contemporaneity that overlays the paintings of past and present, self

and others.