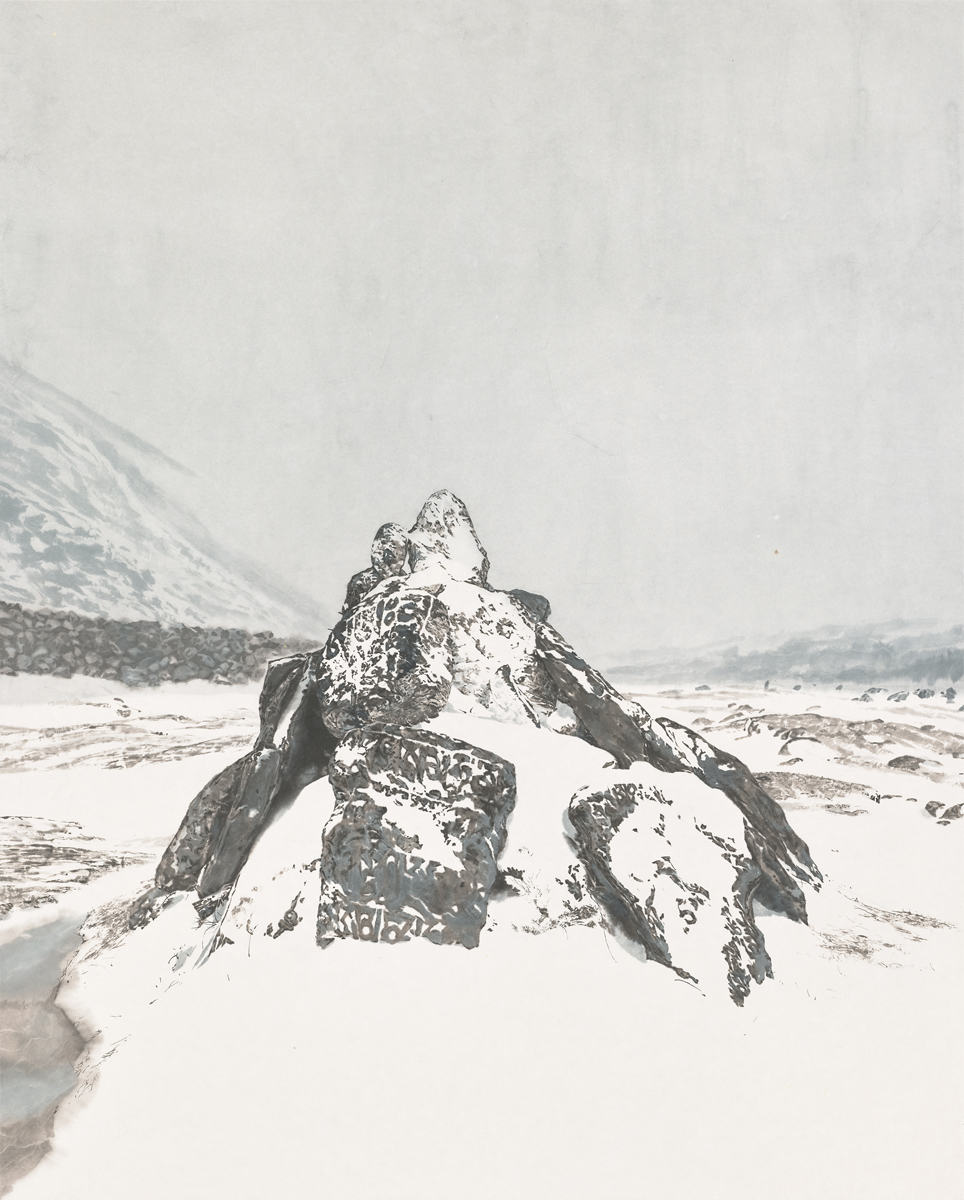

The

sound of ice peaks rustling over the apex of the Himalayas is called the voice

of God. Nobody knows what this voice wishes to convey, although it never ceases

to hit the eardrums of the determined climbers. The artist focuses on a short

mantra, established as a magical language under the religious capture of such

meaningless utterance. -

“The Power of Resonance Streaming out from the Language of Stones: From

Letter-abstract to Painting-abstract (written by Kim Nam-soo)

#1. “A ‘world of stone’ exists in the great nature, and animals already know

the ‘human’ in the abundant world. Now, the time has come for humans to

realize!”

Could there be an artist

or a work who receives inspiration in a spark of an instance and acts right

away? No. Not to take in, but hitherto readily in-taken, as if a propositional

clue exists? While reviewing Hwang Kyu-min’s portfolio (hereinafter referred to

as Hwang), I came up with an erratic imaginary that the key to unraveling the

artist’s (or the work’s) intention was “already” endowed in me. An antler of a

white deer struck like lightning, sprouted right on the forehead, and thereupon

exploded like a flash. Sure enough, in August 2019, his first solo show’s theme

(as well as the title) was 《Muh Emdap Inam Mo》.

In the

given foreword, “The Power of Resonance Streaming out from the Language of

Stones: From Letter-abstract to Painting-abstract (돌의 언어에서 흘러나오는 공명의 파워: 문자-추상에서 그림-추상까지),” choreography critic Kim Nam-soo has announced Hwang’s

commencement as a “self-recognizing great nature” by discovering Yoon

Byeong-yeol’s theorization of the “speaking stone” implicated in the paintings

depicting the Himalayan “stones.” But before, a remark is made on a quote from

the German philosopher Heinrich Rombach: “From the stone, man learns the

immutable (das Unveränderliche).

The stone over-puts (Über-Stellen) its

immutability in the place that transcends the mutable.”3) Another remark that

requires our attention on top of this is that “muh emdap inam mo” is an

inversion of the Tibetan Buddhist mantra “om maṇi padmé hūṃ (ॐ मणि पद्मे हूँ)” in Sanskrit. This mantra is a resonance of every

respective universe, creating a silent swirl around and throughout mirrors and

wells. What an exhibition–to whirl the paintings, space, and resonances within

those paintings altogether!

In April 2020, after less than a year from 《Muh Emdap Inam Mo》, Hwang held his second solo show under the name of 《Penetrating Stone》. However, the presented

thematic—a stone that seems to fathom the mind—was not that of the Himalayan

stones anymore. Surprisingly, what he had picked up instead was a “black

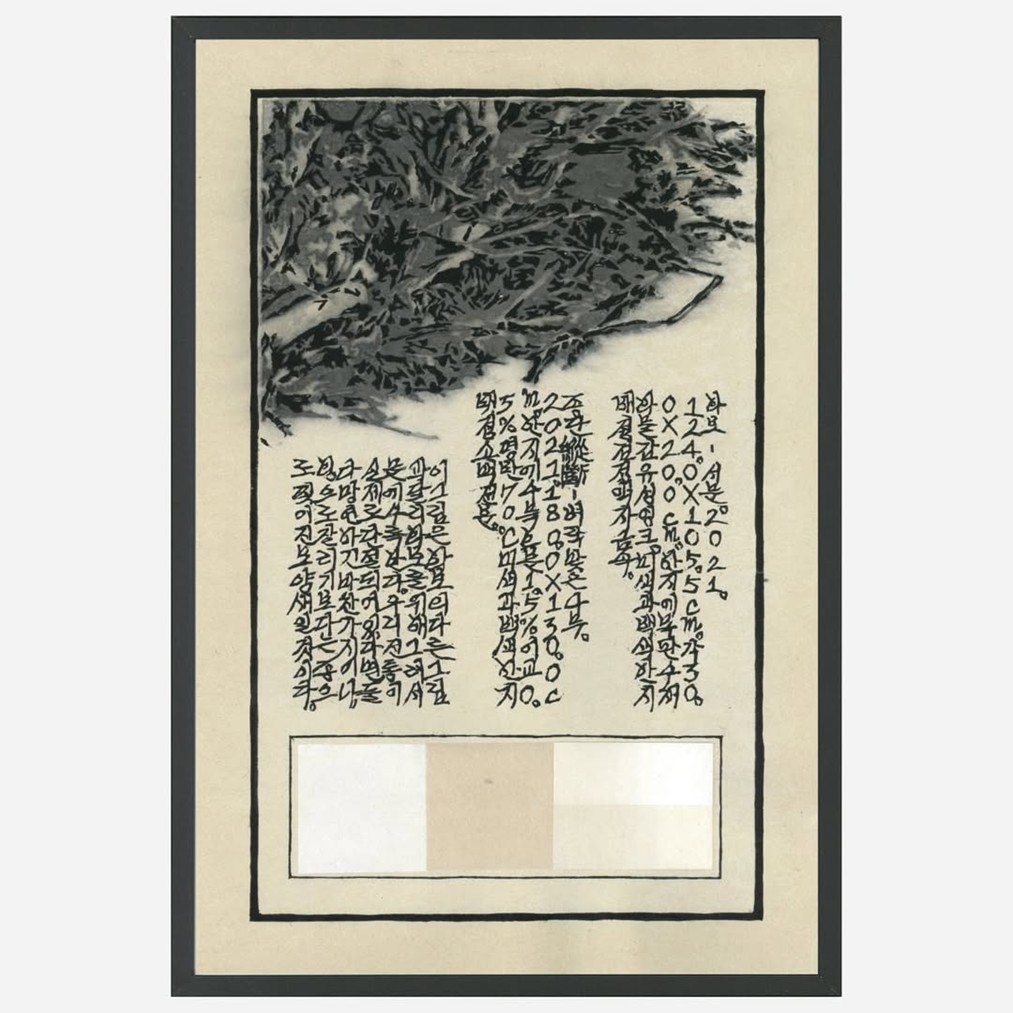

inkstone.” This thread of the inkstone is told to be conceived from Ch’usa Kim

Jeong-hui’s (추사 김정희 秋史 金正喜) saying–“칠십년 마천십연 독진천호 (七十年 磨穿十硏 禿盡千毫),”4) which means “during

seventy years, ten ink stones have worn out, and a thousand brushes have turned

stubby.”

If the stones in 《Muh Emdap Inam Mo》 were full of a presentiment on ripping open the “rear sky (뒷하늘

後天)” of the “mandate of heaven (바탈 性: 天命)” by a unified pulsation of sound-resonance; the stones in 《Penetrating Stone》 were a mere object, an

outdated institutional symbol of “동양화 oriental

painting”* waiting for its anachronic body to be deconstructed. The visceral

voice (육성 肉聲) of the stone’s mythological cosmogony

disintegrated like an illusion and left only a “penetrated stone” in the

absence of the utterance. This year’s show in the OCI museum stands conspicuous

on the continuum of these exhausted ink stones. I was speechless and numbed

since the stones refused to be connected. Impoverished eyes often blinked;

undone imaginaries whimpered in a subtle rhythm.

#2. “What the exhibition speaks of as a device of reverberating

machinery–leaking the mantra of an inverted mirror image–is that itself can

become a contemporary phenomenon of art that flows regardless of the finitude

of modernity.”5)

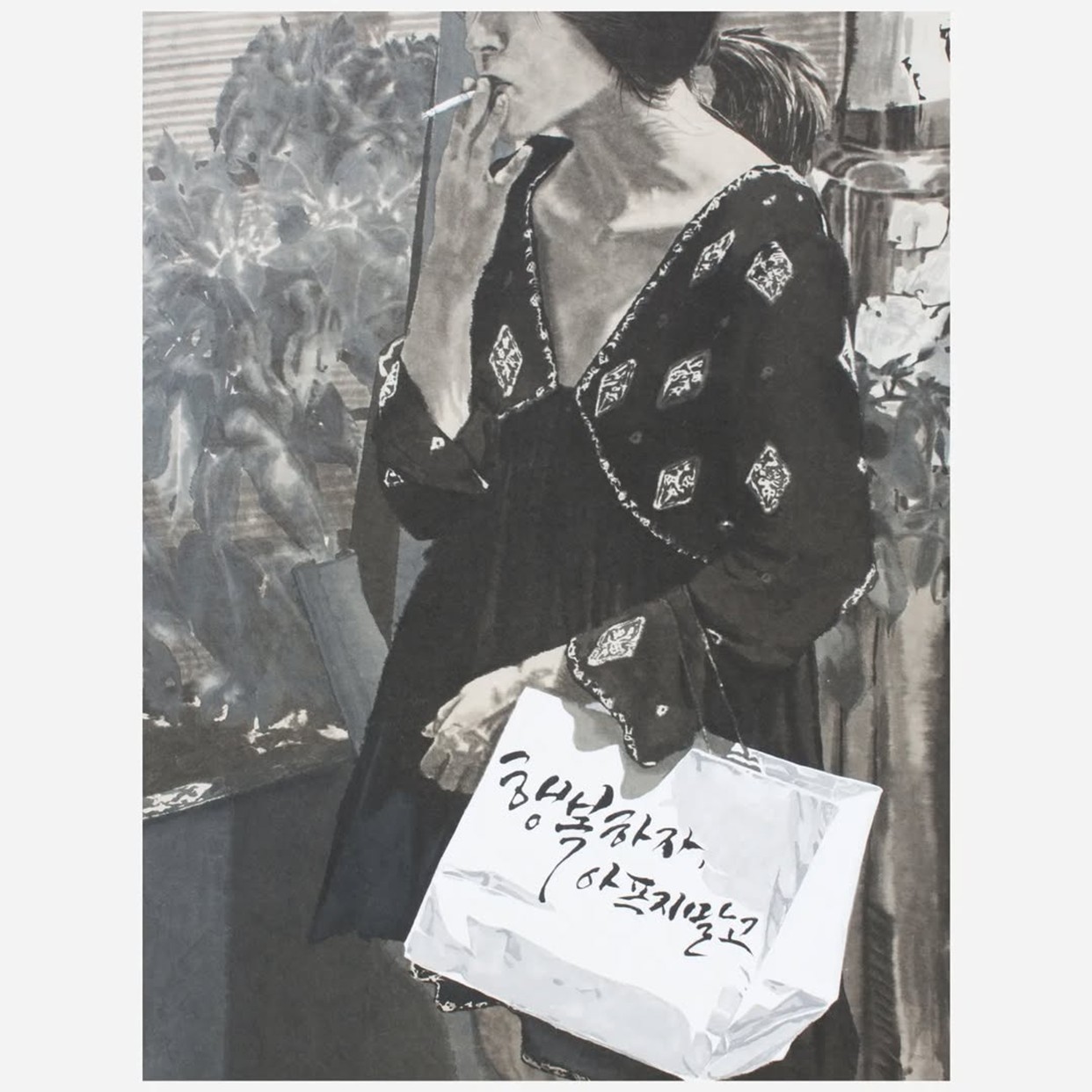

We shall let go of the 《Penetrating Stone》 from two years ago. Hwang and I had many meetings and shared our

unresolved thoughts. Rather than delving into his reason for constructing 《Hwang’s Manual of Eternal Classics》, the

stones of 2019 and 2020 arose in need of a rearrangement. One stone climbed on

top of another. Another rolled next to the other, subsequently walking away

from each other–ready to be cracked open. On one day of studio visits came a

moment of the stones breaking down, resembling the eruptive moment of my former

erratic imaginary.

After a while, the imploded space mutated into a complete

void. And at last, residues of implosion disintegrated into insignificant

molecules on the way back home. Rombach’s immutable stone shattered away. Not

to mention, the sacred stone was nowhere to be found. Because it was Hwang’s

fascination with the stone that fed the stems of associated critical texts, the

root of this text had to linger in hesitance on the very surface of the soil.

Moreover, since a work of institutional analysis-critique of oriental

painting’s pedagogy stood in the stone’s absence, what critique could perform

was only to follow the work’s embedded criticality. A mantra, an image, and a

letter commingled in the place of dispersed stones: a return to the

reverberating sound-resonance. Once again, we shall murmur om maṇi padmé hūṃ.

Yet still, both Hwang and I were lost in our way amid a foggy labyrinth.

Anonymous cracklings of unanswered questions–why two stones permeate each

other, inducing a break (simile); what kind of exchange in intentions takes

place to point out and fracture (metonymy)–bloomed by the concealed desire of

the antler (metaphor) that has grown during the past two years. Above all, the

work’s essential nature of “being” a critique was obstructing the path behind

an illusion presented by the paintings’ manifested materiality.

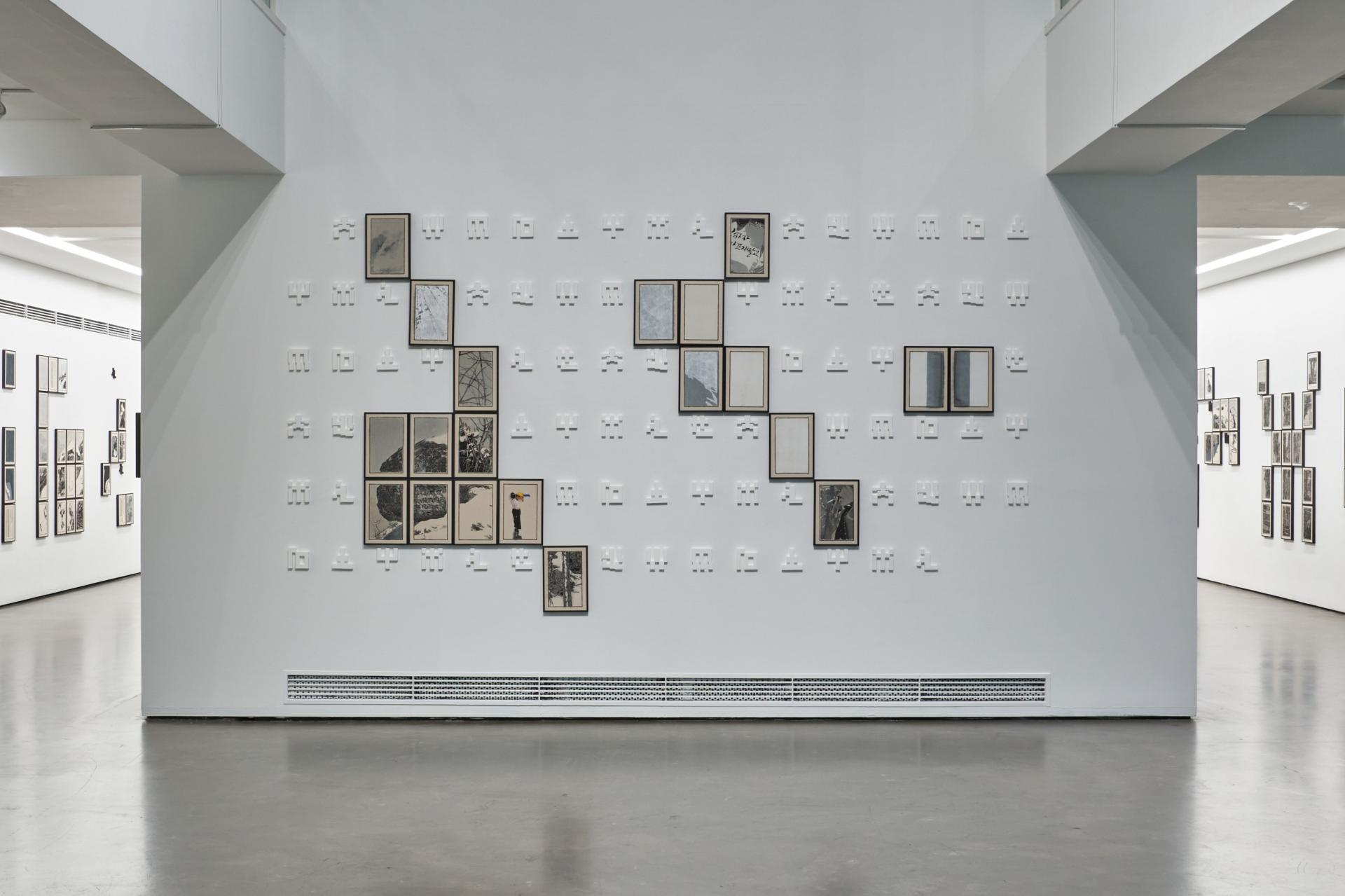

Nonetheless, we

should stay alert to recognize that Hwang is not only “exhibiting” his works in

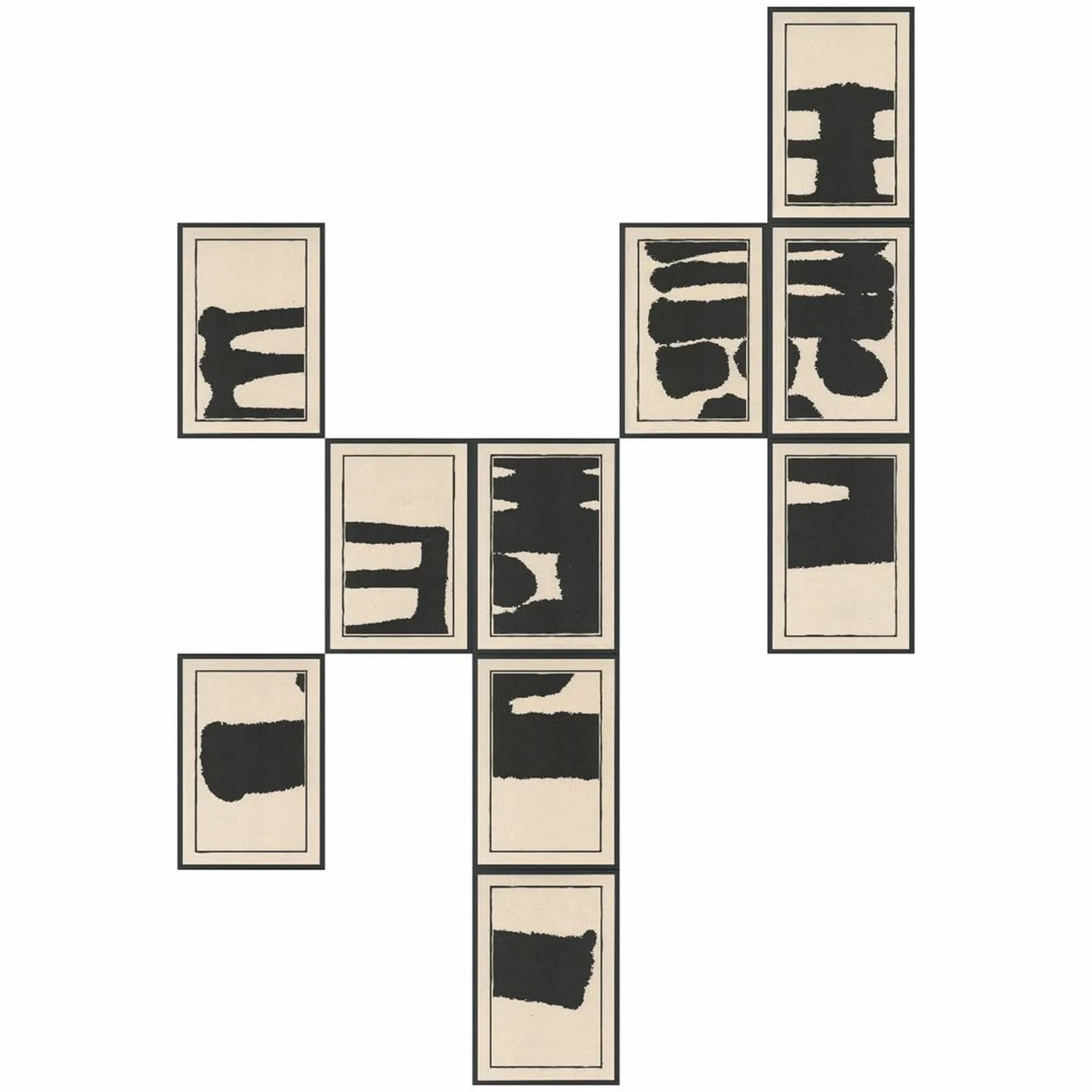

the present show but also curating himself as a “curatorial event.” For this

purpose, he has put exorbitant effort into set-production regarding the

intricate relationship between the paintings and the letters. He has

deconstructed every single painting–including the ones of 2019 and 2020–to meet

the ends of this “curated event.” Now here appears a key to unraveling this

show. A temple, it is, where 《Hwang’s Manual of Eternal Classics》 unfolds

itself.

If the set-up of Seoul Art Space Seogyo (Muh Emdap Inam Mo) was analogous to a

passive experience–to take in the mantra, paintings, and letters as they

are–the present show, i.e., a “curated event,” arises “as” an experience–a

happening concomitant to the active reconstruction and restoration of the

viewers. It is a duration for the viewers to make their respective mantra/a

sacred book by intervening-reorganizing the paintings and letters. Hence, by

all means, 《Hwang’s Manual of Eternal Classics》 is an incident that makes the momentum of epiphany possible

throughout the duration.

Nevertheless, the starting point of this determination

still seems to lie in Seogyo. Not for the actual space of Seogyo, but because

he has summoned the past theme of 2019 once again. Yes, the mirror reflection

of “muh emdap inam mo” is looping/re-reflecting itself on the surface of a

well. While constructing this temple, Hwang asked tenacious questions about the

structures of paintings and letters since they shall demand a reconstruction

from the visitors; yet, the paintings and letters refuse a reduction to a

formal display.

If then, every painting and letter should serve as an index of

a fishing net of an imaginary. Every respective index must become a venerated

mantra and its self-sacred book. Hence, what we encounter here is indeed a

faithful event of a particular device–the reverberating machinery that bleeds a

mantra out.

#3. “It’s true that everything has its Personal Legend, but one day that

Personal Legend will be realized.”

A stone in an egg. It is the world, the holy spirits, and the universe’s

breath. Like Abraxas has flown out of the egg, a stone can only open a new

world through an autonomous breakthrough. For a long time, the persistent

inquiry of the alchemists was of a stone—the lapis philosophorum (the

philosopher’s stone). This stone redeems, becomes gold, enlightens, empties the

mind, and nurtures the nucleus. Hence, the alchemists’ destiny was to

scrutinize–meaning that the days grew deep in fostering the intelligence of

knowledge.

The west end of Eurasia turned obsessive over creating this

“non-existing stone,” while the east end practiced transforming an “existing

stone” into a sacred one by engraving texts on its surface. However, although

alchemy may produce gold, that golden stone is not the lapis philosophorum.

Yet, on the other hand, a stone inscribed with the uttering voice of

realization is sacred. Hwang has met those sacred stones that people in Nepal

respect. They walked anti-clockwise on the encounter of the revered stone and

prayed. In the morning, they petted the stone while murmuring “om maṇi padmé hūṃ,” a mantra that eases

the day ahead.

As seen above, the stone was not just a stone but a holy saying, a mantra, and

a sacred book. On it was bestowed the breath of Buddha. So yes, the stone is

prodigious mythology for those inhaling such exhaled aphorism. Why? Because the

stone is the axiom; because there resides only the venerated speech in the

stone’s dispersion; because the stone’s uttered vigor (숨돌 氣運) has ascended to redeem

those people every single day.

Choi Si-hyung (해월 최시형 海月 崔時亨) spoke of a novel

reverence–to serve the sky (경천 敬天), to serve the people

(경인 敬人), and to serve the 몬

mon** (경물 敬物). However, the sky and the people and the 몬 mon are not independent. The stone, the saying, and the people are

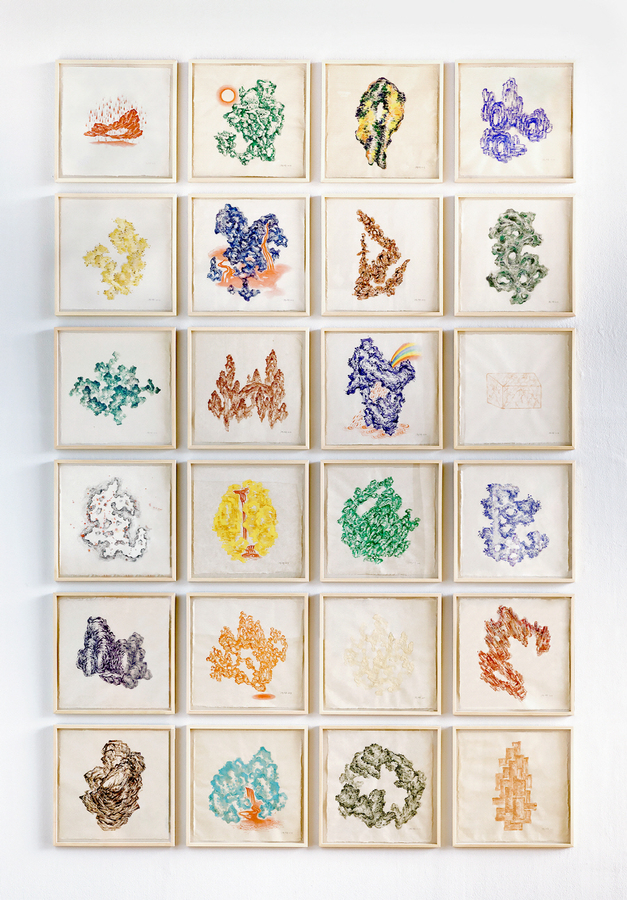

altogether one. The ink stone of Ch’usa has poured out myriads of paintings and

texts as its base wears out.

How many images and texts should there be for the

ink to erode the solidity of a stone? A stone–a trivial memory disk of every

minutia of the universe; an inkstone–an indifferent fountain that streams out

the black liquid. Yet, what this black liquid draws and writes lives longer

than a thousand years since there emerges a saying, i.e., the speaking breath (말숨), right in the place where the stone diffuses. Thus, this place of

diffusion and ascent is what 《Hwang’s Manual of Eternal

Classics》 signifies–a place where the stone has

imploded. Here, the shredded ink stick of 2020 metamorphoses into an

innumerable amount of Classic Drawings.

An order of the symbolic emerges once

again. Within his practice, Hwang makes a constant analogy to the late

nineteenth-century Chosun dynasty best seller Painting Manual of the Mustard

Seed Garden (개자원화보 芥子園畫譜) alongside other classic

manuals and critiques of that epoch. Likewise, the mounts holding the Classic

Drawings on the walls represent a selection of ancient characters, e.g., sky (하늘

天), water (물 水), fire (불 火), rain (비 雨), stone (돌 石), soil (흙 土), grass (풀 艸), tree (나무 木), human (사람 人), text·drawing (글·그림 書·畵).

However, these characters belong to the

place where the stone has shattered, where the speaking breath unveils. Hence

affirmative, they are invisible. Concealed from our sight, they pull the

universe with the reverberations of sound. Furthermore, by upholding the

Classic Drawings, they create a polyphony of images and letters. No matter

whether it is “to tell a story,” “to draw with the outlines,” or even “to draw/paint

with the drawings/paintings” that Hwang makes the principle of his assembly,

participation from the visitors will come to dismantle the organized space. The

initial arrangement will therefore gain different colorations of sound as long

as subtle trembles culminate. It is the world to be as it is–the world itself

being as it is.

Here stands a temple which is also a copy of a giant book. Above the entrance,

are inscribed light (빛 色) and strength (힘 力). Only by earning them will we be able to realize and wander

inside. If not? Then the lion’s roar (사자후) awaits for

an unexpected startle. Hal (할 喝)!