What

is the meaning of gravity in a painting? It can appear as an imaginary force

which organizes the order of the three-dimensional space within the painting,

or it can appear as a real force acting upon the physical body of the painter

and the canvas covered in paint. In both cases, however, gravity is not a force

contained on the optical flat surface of the painting. If a painting is

approached innocently as a flat space for the paint, there will be no space for

gravity to function.

Therefore, if gravity can be felt within the painting, for

whatever reason, it is because the painter either felt the need for gravity and

intentionally inserted it there, or simply tolerated its accidental presence.

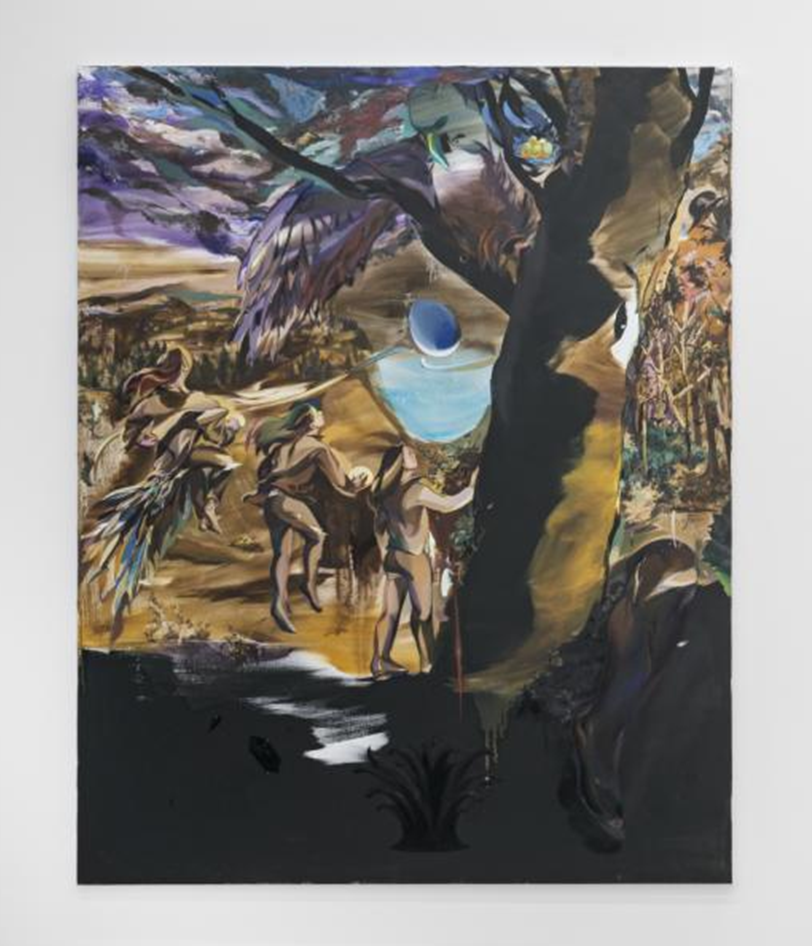

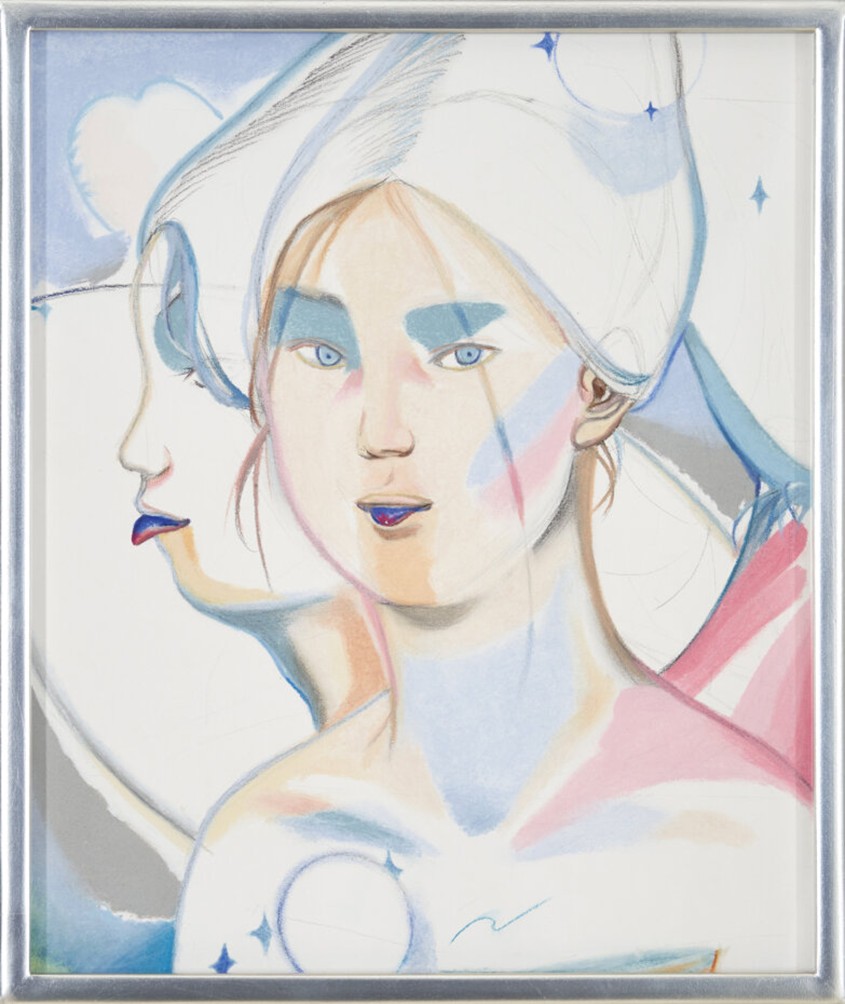

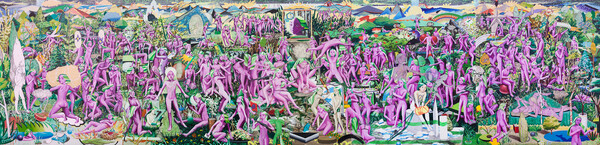

Looking at the past works of Soojung Jung, it seems as though up until now she

has not felt the distinct need to introduce gravity into her paintings. Her

works are not realistic portrayals of three-dimensional worlds, but rather are

closer to an attempt to conjure up a world she wants on a two-dimensional surface.

So, rather naturally, her paintings have been filled with a sense of

weightlessness.

In

her two previous solo exhibitions, 《Sweet Siren》 (Rainbow Cube Gallery,

2018) and 《A Homing Fish》 (Gallery

Meme, 2019), Soojung Jung increasingly used an intentionally disjointed

arrangement of exterior lines and blocks of solid color forming differentiated

objects, or omitted sections in the painting, revealing them to be solely the

result of brushwork. Nevertheless, the paintings did not disintegrate into

tatters but rather remained firmly stitched together—and created a liberated

world where plump bodies run and play.

The human bodies, which appeared to be

in female form, conveyed a three-dimensional feeling and a sense of emotion

which contrasted sharply with the thin surface of the painting. These beings

were not arranged on land as dictated by perspective, but rather welled up as

lumps and bumps across the entire surface of the painting. These soft and

malleable beings—these animals, plants, landscapes, and panoramic views which

come and go freely within the fluidity of the paint—lie comfortably on the

support structure of the canvas. While displaying a sense of mass innate to

objects that cannot be pushed or pulled by an outside force, their arms, legs,

heads, and butts moved at will, or remained obstinately still. However,

although the paintings capture a sense of up and down through their postures, a

sense of gravity is largely absent.

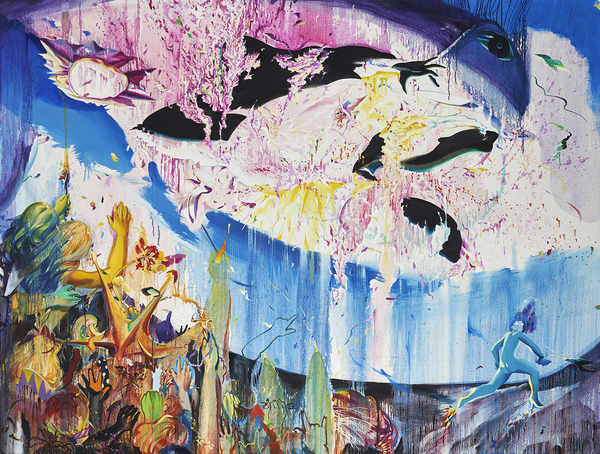

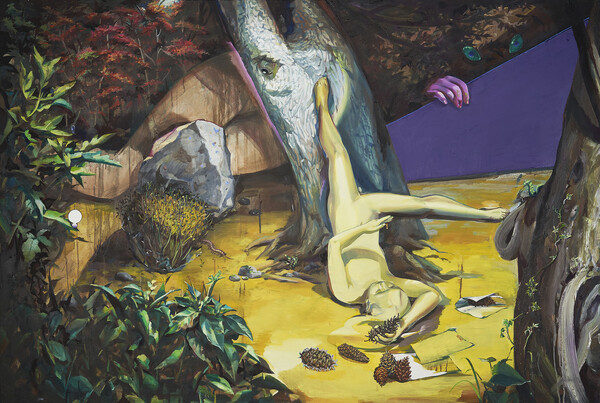

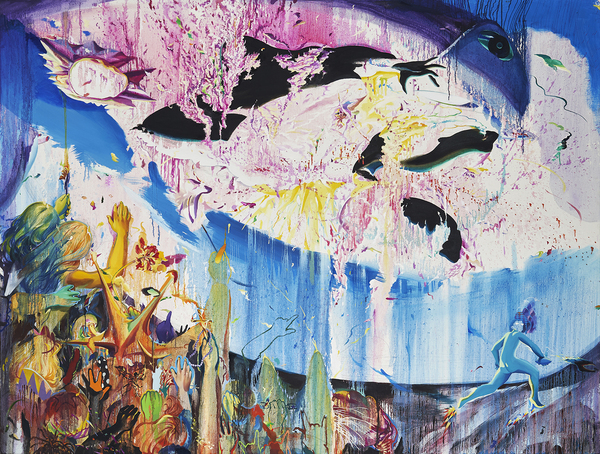

However,

this exhibition, 《The Star of

Villains》, is overflowing with images of things soaring

upwards against the forces of gravity. That is, it appears that Soojung Jung

wanted to draw something different from her previous works. How should we

understand this? Looking at her drawings, we see rockets and flying machines,

and one can glimpse a clearly drawn image of mars based on the science fiction

genre. However, this work has not been completed as a graphic novel or a

narrative type of painting. Indeed, as if the order of time and space has been

shattered, each painting—both existing on its own while also overlapping with

the next—shakes and vibrates.

Take the painting No graffiti here,

for example. Above the flying saucer that is either landing or crashing, there

is a person who is painting, and at their feet is another person who has

collapsed. They are surrounded by all types of flying machines and painting

tools. Here it is easy to imagine a destroyer-artist painting wherever they

like. However, because the people within the painting are themselves holding

brushes, it is difficult for the person outside the painting to decide on one

story for all of them.

Are the people with brushes drawing graffiti on the

flying saucer after having captured it? Or, have they drawn the image of flying

machines into the world of the painting, where they previously did not exist,

destroying the originally pastoral imagery in the process? According to what

criterion can we distinguish between that which has been drawn with the brush

of the artist, and that which has been destroyed?

Among

the multiple stories that can be told, here is one of them. The

artist—attempting to break away from the world they have constructed in their

paintings and escape the gravity of their constructed world—dreams up images of

painters coming and going across the canvas and flying machines freely

traversing the painting. However, the things flying up from the painting are

revealed to be the act of colliding with the flat surface of the canvas and

destroying it, or the destructive process of being destroyed on its own.

The

painter is split; the flying machine breaks into two parts; the skeleton

shatters into four pieces; the painting breaks apart into shards. In the end,

what dominates the surface of the painting is not the science fiction flying

machine, but rather a kind of ball—a moving object which has been quickly cast

out, struck, exploded, destroyed, and has crashed—it’s the image of a cluster

of energy. For example, in Fly, which unites two canvases as

one painting, there is a white, round thing which has been cast into the middle

of the painting.

Although it clearly looks like the focal point of a forceful

impact, it is difficult to know exactly what it is. What is clear is that the

force of it being thrown into the painting has caused the remaining elements to

move. In fact, all of the elements appearing in the painting, as moving

objects, are homologous with the ball-like thing. A tumbling mandarin and a

watermelon split in half, a seed covered in dandelion fluff, pieces of paper

with butterflies and dragonflies drawn on them, and the people plummeting

towards the earth all have bodies that are imperfect flying machines. However,

they float temporarily by riding the shockwave.

The

ball- and disc-like shape appears repeatedly in other paintings. While it does

look like the flash of an explosion, a sparkling eye, or a screen, you could

also say it is a “hole” if you don’t think too hard about it. It is both the

focal point where the force that has made a hole is concentrated, and also the

point marking the expanding epicenter of the destructive force emanating from

the hole.

Different than a vanishing point or the center point of gravity, this

dynamic point—which creates an uneven field of power on the flat surface of the

painting—is in a way simply a large blotch of paint made by the painter’s brush

being pressed to the canvas. The painter, who is both a creator within the

world of the painting and an outsider to that world, uses a brush to poke their

way into the world they created. In this world, the brush is a powerful and

absolute weapon; however, as the objects made by the brush are not simply

passive blotches of paint, a collision of forces is inevitable.

The result is

something like an action painting. The painter does not only wrestle with the

canvas on a physical level with a brush and paint, they also enter and fight on

the imaginary surface they have created. Considering that each painting makes

manifest a designed and directed scene, they look like a historical painting

that ideally represents heroic battle of the painter. However, that battle—as

an optical and physical process taking place in real time through the eyes and

brush of the painter—leaves clear traces within the painting.

The

speckled and trickling of paint and layered paint freed from the constraints of

the rough sketch reveal the unique amorphousness of the painting, which does

not point towards a- distinct form by nature. Unlike past works, in these new

works the translucent traces of watery, trickling paint leave literal stains on

the scenes which are structured like a comic. However, these paint stains do

not nullify linear composition, but instead function as an element which imbues

the story of the painting—that is, the story of the painter fighting with the

world they have created—with a sense of movement and vitality.

If there is a

consistent hypothesis presented in the paintings of Soojung Jung, it would be

that the power of the pictorial thing can be amplified not through its purity,

but rather through its hybrid nature. Within the bounds of the painting it is

not just to leave over the most painterly to concentrate it, rather, there is

also the ambition of the painter to create a third world that is not limited to

either side of the binary of real or imaginary, flat or three-dimensional, or

momentary or continuous—and creating such a third world is achieved by

expanding the painting and inserting all types of things which were originally

not there.

Our

Starman, which is both the climax of this exhibition and the last

piece to be created, offers a glimpse of the new horizon towards which Soojung

Jung now sets out for after finishing these works. The painter’s self (which is

created through the collusion of the painter and the world they create), the

fragments of that world, and the incarnation of the force that appears

alongside the destruction of that world are all concentrated in this single

painting. Here the circular disc shape appears as a contorted and twisted

horizon which exceeds the painting and expands in size.

The blotches of paint

splatter in all directions, spilling and running both up and down—and this

abundant energy strangely gives rise to a crooked sense of space. It is both an

unknowable entrance to a new world and the potential territory of a pictorial

dream as transformed space. In principle, a painter can paint anything, and

therefore they become the king of the world they draw. If that is the case, how

can this king draw a map of a territory for an unknown place that they have not

yet drawn? While destroying the world she has made and then recreating it

again, Soojung Jung finds opportunities to expand that world. Indeed, like a

silkworm ripping through its cocoon, this is the journey of a painter

repeatedly being born again.