Magic,

fantasy, gods, and heroes have vanished. In the past, people invented mythic

figures and lived under their control, carrying out predetermined tasks. Today,

fate rests in our hands; the future is a time realized through relentless

effort. With life’s joystick handed to us, we seemed destined for freedom and

passion. Yet amid reels and shorts that mass-produce stimuli and dopamine,

those who chase ever greater pleasures are left with inertia.

For our parents’

generation, labor and leisure were separate domains. After work, office workers

could pursue hobbies or play games; it wasn’t strange to set routines and order

in life. In this climate, a politician’s slogan about “evenings with family”

now rings hollow—an industrial-era echo—because in a capitalism that compels

labor and production, safeguarding our capacity for leisure and play grows ever

harder.

This

essay looks at the ecology of people who have forgotten how to rest in an age

when “burnout” has gone viral. Focusing on SANGHEE’s solo exhibition 《Worlding…》 (Audio Visual Pavilion Lab,

2023.12.10–12.31), it explores labor and the feeling of ennui as existential

reflection. Titled after the exhibition, Worlding··· (2023)

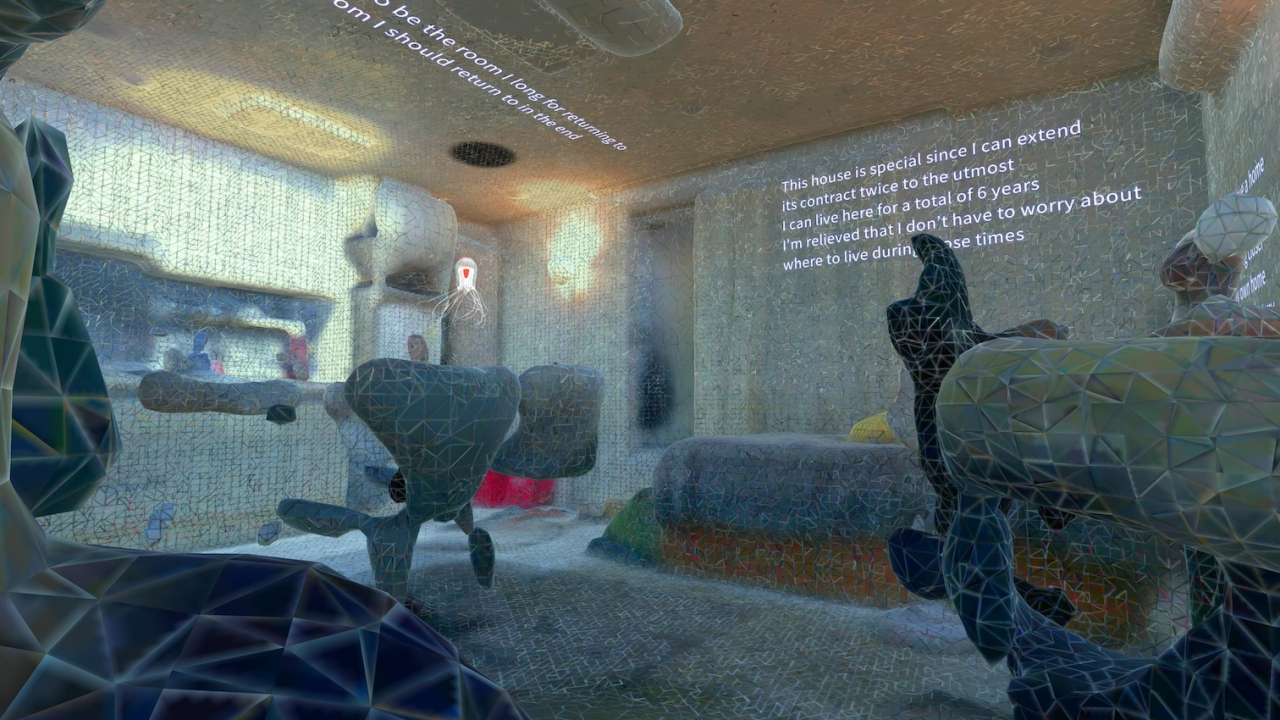

is a participatory VR work that adopts the form of an asynchronous online game:

unlike real-time games, it compels solitary play without user-to-user

interaction.

As “asynchronous” suggests, each player’s actions are linked not

in real time but as traces with a time lag. Borrowing gaming’s image of fun and

enjoyment, SANGHEE speaks to the sensations of bodies laboring in the digital

industrial era and, against the backdrop of instant gratification and fully

individualized worlds, reconsiders the affect of “ennui” as an inner mode of

thought.

Game Stages and the Labor of Play

Worlding··· begins

from a concrete narrative. The viewer/player receives a handover from a

predecessor and starts work. The task: bury a giant who has emerged in a swamp.

Appointed as the swamp’s watch, the viewer shovels soil over the immense corpse

by day and returns to quarters by night to read the predecessor’s log. Most of

the playtime is consumed by burying the giant. And then tomorrow comes. As if

yesterday’s labor never occurred, the body you covered lies exposed again. Like

Sisyphus, the punishment of labor repeats anew.

As

noted, SANGHEE borrows the grammar of games—evident in how the work “stages”

its narrative. Typically, game space expands meaning as a vehicle for concrete

player experience; narratives unfold via stage-building, structuring the

beginning-middle-end of gameplay, with players completing quests stage by

stage. In Worlding···, whose day-by-day stages are

separated into units, there are no quests. More precisely: each day, a prompt

appears—“Fill today’s labor quota”—but there is no reward for doing so. Rather

than advancing the story through stage progression, the work sets a stage of

the same scene—yesterday and today alike—and offers a quest without

compensation.

The only sign that time passes is the on-screen image of a

controller: represented as two hands that age with each stage, turning

progressively dark and shell-like. The two hands ceaselessly shovel soil to

meet “today’s labor quota” demanded by the burial. Controlled by two hands yet

touching nothing, grasping nothing—the image conveys a hollow sensation. This

powerless, repetitive motion piles earth again upon the giant whose body will

be unearthed tomorrow. The endless burial recalls laboring bodies bound

insubstantially to digital infrastructures.

Waiting for a Game to End

Crowdworking,

platform labor, even AI labor—utopian visions trumpet that technology lets us

work “anytime, anywhere” with “freedom.” Cloaked in the logic that future

technologies will reduce drudgery and liberate our lives, this appealing

program claims legitimacy. But are workers truly liberated from labor? As

technology and society accelerate, we too must process more, faster. Even when

we leave the office physically, we do not escape work. As with the collapsing

boundary between virtual and real, the border between workplace and everyday

life has eroded.

Depending on the social use of technology, companies outsource

non-core departments through in-house subcontracting, dispatch, and

externalization, tethering workers in non-worker guises to the network of work.

Being “online” and connected in real time—always and everywhere—means bodies

are constantly placed in a state of labor, with no clear border between labor

and leisure. In a hyper-accelerated world, slow bodies are ruthlessly culled.

The more quickly automation and autonomy advance, the more rapidly individual

disempowerment proceeds.

Within

these conditions, SANGHEE engages with the performative nature of labor through

gaming’s terms. If execution is obeying commands and performance is generating

events through repeated bodily training, then the laboring body in this work—an

image executing tasks—offers a critical meditation on the performativity of

contemporary labor. This emerges in the work’s principal affect: tedium and

“ennui.” While games are often discussed in terms of pleasure, fun, immersion,

or addiction, the artist adopts gaming’s form to speak about ennui—proposing

that viewers shape the ground they will tread through the game’s staged

narrative.

No one sets “today’s labor quota,” and the game’s timeline has no

guaranteed end. The physical body gripping the controller syncs with movements

in VR and repeatedly re-enacts tedious labor. Viewers map their bodies onto the

bodily image in the VR game: at first focusing on a mismatch of sensations,

then, as identical daily stages pass, feeling sore arms and shoulders as their

bodies attune to the one on screen. Play becomes painfully monotonous.

Rediscovering Ennui in a World Perpetually Loading

Those

who feel ennui dwell in emptied spaces. In vacant lots where communal order and

life’s direction vanish, one is easily exposed to ennui. In today’s society of

doing, working, and eating alone, we become subjects of narcissistic enjoyment,

choosing isolation while being captivated by virtual scenery. SANGHEE

transposes this contemporary vista into virtual space: solitary labor,

movements with no end in sight, a world without others. When one viewer removes

the headset and leaves, another—the swamp’s next watch—arrives.

They do not

meet. The gallery viewer inherits the predecessor’s task and repeats it.

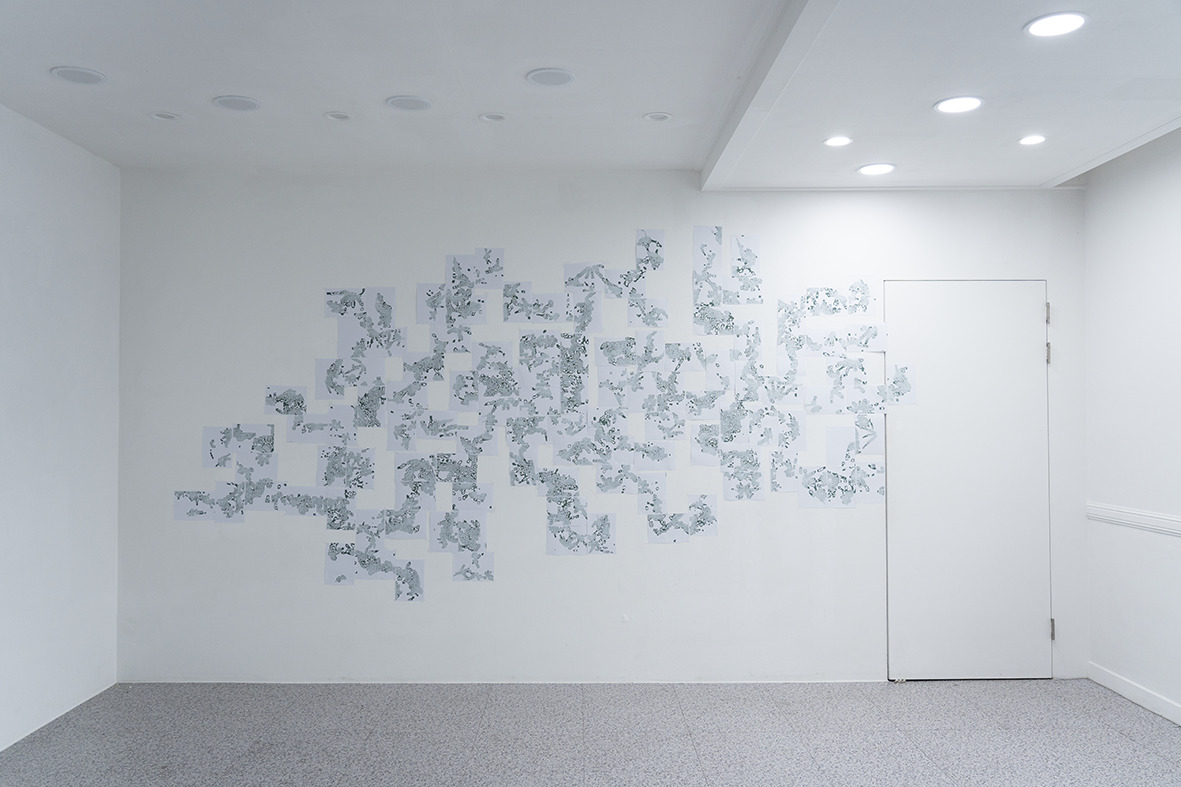

Notably, what happens after the player removes the HMD is crucial: freed from

the long playtime, the viewer slips off the headset—head throbbing, shoulders

heavy—and sees their accumulated VR data printing onto paper. Depending on how

the giant’s body was covered, the data draws a terrain map. The high-spec VR

ground becomes a 2-D dataset stacked in space; meanwhile, in the basement, a

screen projects a combined map formed by aggregating all participants’

execution data. Viewers discover another trace of labor through a coupling of

physical and virtual spaces. In short, Worlding··· constructs

a world where “nothing happens,” yet makes palpable a community linked purely

by traces.

The

chief symptom of ennui is perceiving time as time itself. The subject of ennui

estranges themself—sensing time as if observing an object—and this proposes the

distance that partitions “you and I,” or the common terrain that binds us. In a

society whose time is packed to the seams—bodies “online” and synchronized

24/7—there seems no room to feel ennui. Here, SANGHEE attempts to

“desynchronize” bodies bound too tightly. From the unburied giant’s death—an

entity whose origin and very nature remain unknown—come stories of ennui and

solitude. Put differently, in the kingdom of fun, where world events are

consumed as images or shells, the artist slows the pace by weighting today’s

time, stretching the world in “loading,” and making a place for ennui—summoning

a solitary, existential confrontation with the self.