The

convergence-arts festival 《The Fable of

Net in Earth》 at Arko Art Center unfolds both online

and offline. Entering the physical exhibition space, I had the sense that

themes frequently addressed over the past two to three years were

comprehensively arrayed, and that the curator intended to further deepen related

discourses.

Recent efforts—attending to environment, ecosystems, and the non-human;

dismantling binary boundaries; following multiple cosmologies; and moving

beyond anthropocentrism—have been articulated via theorists such as Bruno

Latour, Donna Haraway, and Rosi Braidotti; this exhibition likewise keeps these

discourses in view. In particular, it rests on a Haraway-inspired conception.

As

Arko planned, the galleries are rendered as spaces of free imagination. Through

speculative storytelling, a practice of “worlding” is staged that calls for a

shift in our grasp of reality and in our methods of artistic practice.

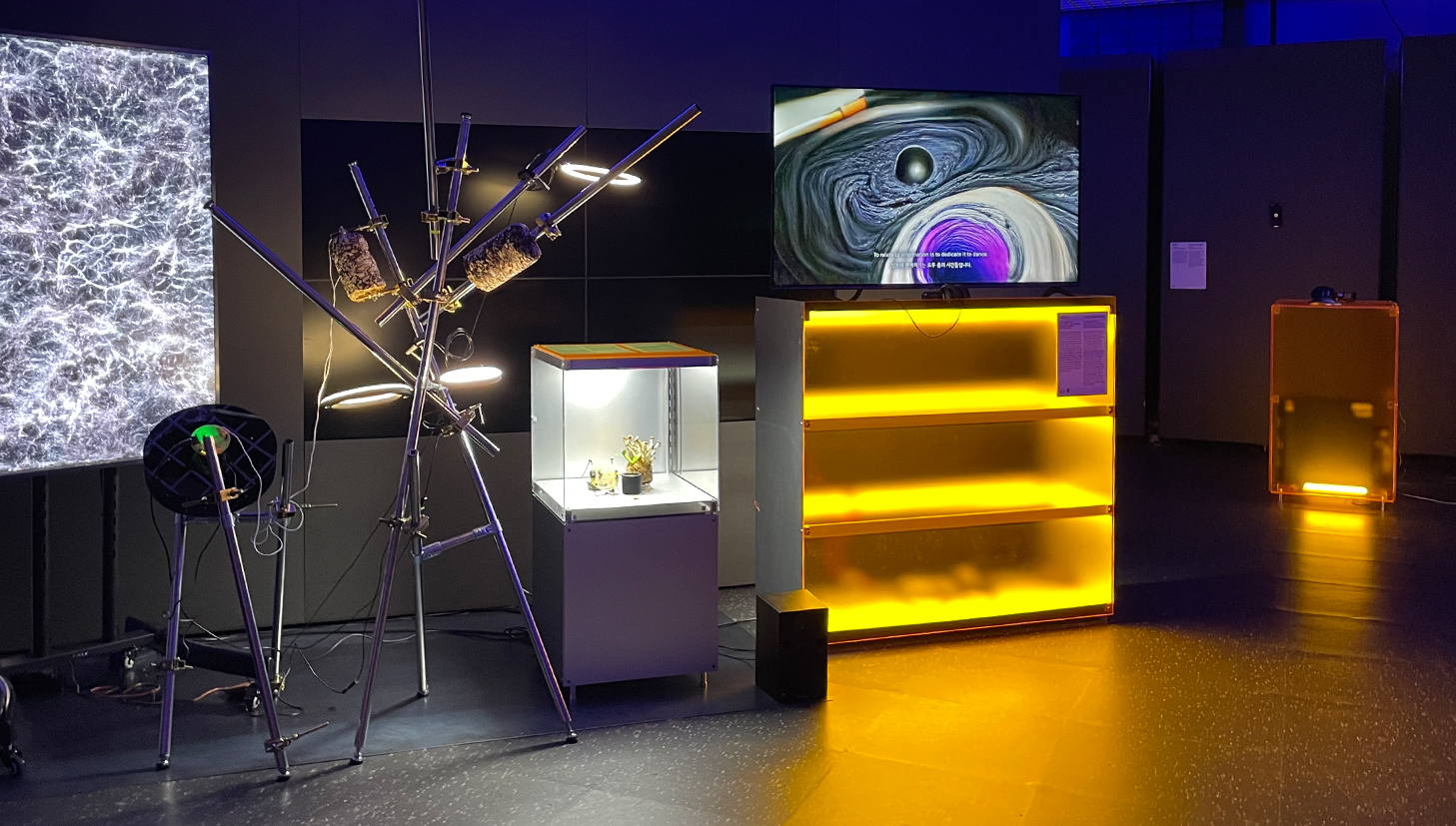

Especially in “The Unknown and the Wild,” the first gallery section, there are

echoes of the 2021 Gwangju Biennale: spiritual elements of the technological

age that seem, at first glance, unrelated are narrated, or incidents plausibly

arising in the wild past are drawn into the present, or stories of spirits

transcending temporality are told.

Living

amid both visibility and invisibility, we sometimes seek to render the

invisible visible—for belief, for proof, and for sensation. Users of

digital-technology systems composed of immaterial elements produce visibility

through screens—monitors and displays. In this world, Gallery 2’s section

“Mutating Worlds” appears to argue for values we should pursue. The speculative

act of thinking the invisible beneath the visible rests on the idea that there

is that-which-exists beyond reality, and on that basis we can attend to beings

other than the human.

In

this sense, the choice of the title “Underground Web” may aim to speak about

what we cannot see—vast, unpredictable expanses entangled like nets beneath the

ground that cannot be summed up merely as “connections.” Our only response may

be to apprehend a complexly connected world through new acts of imagination.

This seems to be the message of the online virtual exhibition 《Garden of Mycelium》.

The

online exhibition presents a virtual micro-world. The premise is that I,

exploring underground, travel through a virtual space. Digital technology has

brought many things, but one to note is the capacity to create what we had only

imagined, in a manner that builds another reality. There, not only our

imagination but the sensory experience of its elements matters.

《Garden of Mycelium》 consists of three

gardens: 《Garden of Zygomycota》,

《Garden of Ascomycota》, and 《Garden of Basidiomycota》. Rather than

magnifying something via a microscope, the premise is that as one goes inward,

innumerable worlds exist—suggesting the possibility of other worlds. And these

worlds do not exist separate from the human world; rather, they may react just

beneath the strata’s surface. Those reactions may remain as minute actions

deeper underground, but even the smallest response would be connected

somewhere. This is not about enlarging small things, but about imagining that

even the small is already composed of yet smaller worlds conjoined.

Such

an interpretation resembles the “oligopticon.”¹ Coined by Bruno Latour and

Émilie Hermant from the Greek oligo (few, very small)

and opticon (seeing), the oligopticon stands in contrast to

the panopticon—which surveys the whole—by proposing a way of seeing that

considers the very minute.² It focuses on how actors entangled within a

structure form networks of connection. The world is not made of simple

structures; amid many mutations, every entity possesses variability that

changes from moment to moment.

In

2004, Latour produced the web project “Paris: Invisible City,” arguing that

while we typically picture Paris via postcard images—the Eiffel Tower

shining—the actual city exists by virtue of what is hidden behind those images.

A city made through innumerable interactions reminds us of the entities we

forget. His project distinguishes what is visible above ground from what is

invisible below, likening the underground to a subway map. He describes a

complex structure of roots sending out fine rootlets and branching anew.³

The

virtual space of the online exhibition does not materialize the invisible

differently in the offline galleries; rather, it virtualizes what exists in

imagination. One might call it the virtualizing of imagination. What we imagine

is visualized and made experiential through virtualization. If we proceed on

the premise that this virtual is not unreal, then through the very act of

experience we come to understand a world and, in that moment, to make that

world.

1.

The oligopticon appears in Bruno Latour and Émilie Hermant, 《Paris: Ville Invisible》 (Paris: Les

Empêcheurs de penser en rond et Le Seuil, 1998), to describe a non-panoptic way

of seeing.

2.

Kim Joo-ok, “Oligopticon and Actor: Focusing on the Experience of Urban Space,”

《Journal of Contemporary Art History》 42 (Dec. 2017), pp. 7–8.

3.

Ibid., pp. 13–15.