Data

Ordinarily, the opening of an art exhibition

indicates the completion of an artist’s work in preparation for the exhibition.

The time leading up to the opening is time in which the artist creates the

artwork, and the opening is regarded as the end of this creative activity. In

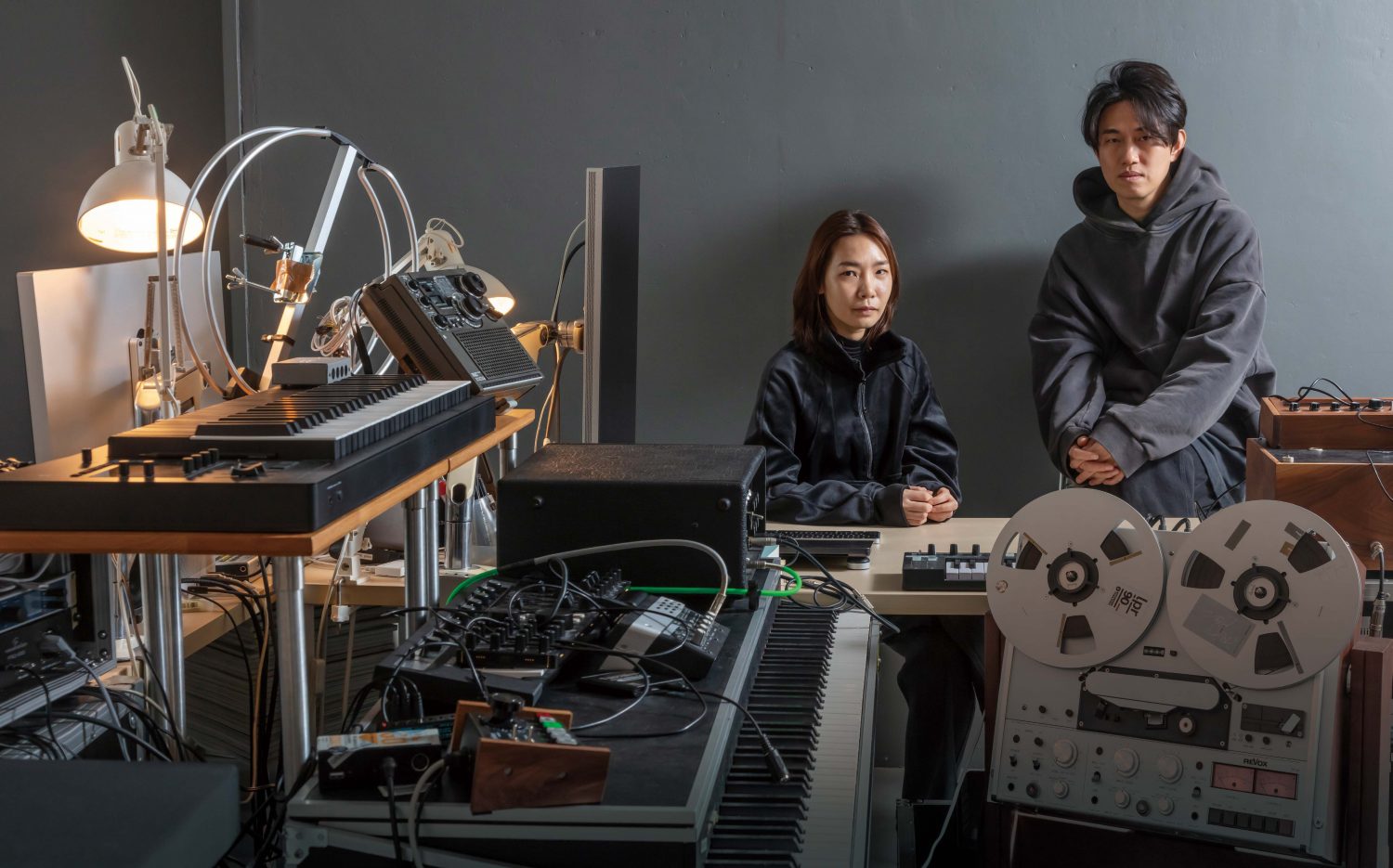

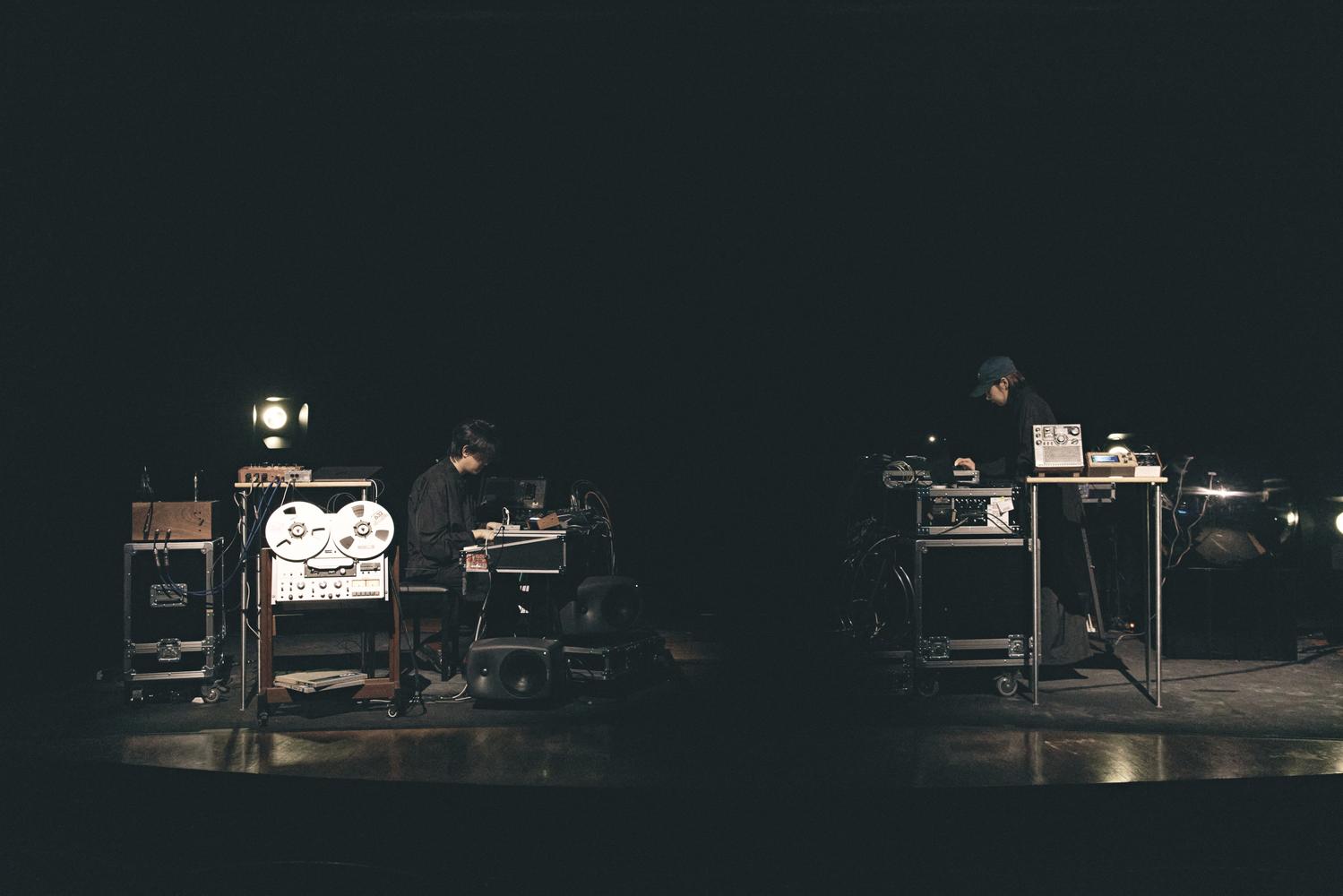

the 2020 exhibition 《Time in Ignorance》, however, GRAYCODE and

jiiiiin instead used the opening to mark the starting point of their work,

arranging the frequency of the sound that was created at the opening concert to

gradually diminish until it finally vanishes from the human spectrum of

hearing. Similarly, in their latest exhibition, the opening of the exhibition

is not the end but the start of their work, as evident in the exhibition guide

placed at the entrance that divides their project into three sections of A, B,

C. While Sections A and B are titled “Data Composition -1” and “50 Days

Exhibition,” the title of the exhibition, “Data Composition,” is actually

assigned to Section C. Why was this single exhibition divided into three sections?

The answer is related to data, the core keyword of 《Data

Composition》.

In The Mathematical Theory of

Communication (MTC), a founding work for today’s information theory,

Claude Shannon proposed a method to quantitatively express information through

the extent of the reduction of the “data deficit.” For example, one might

decide whether to receive a medical check-up this year by flipping a coin,

assigning “Yes” to the head and “No” to the tail. Until the person who chose

this decision system actually flips a coin, there is a deficit of data required

for the decision, which can only be completed with the data collected from the

flip of the coin. As such, the “-1” in “Data Composition -1” implies that the

system for the exhibition is prepared, but the key data is lacking, wherein “50

Days Exhibition” is dedicated to the collection of the said absent data. As

such, the exhibition 《Data Composition》 is designed to be

completed upon inputting the data collected over the course of 50 days.

Therefore, the exhibition that opened on January 15, 2021 at Sejong Museum of

Art 2 comprises only one-third of the entire Data Composition

project. Visitors to the exhibition are placed in Section B and become

providers of data required for the completion of the exhibition. Poetically

expressed in the exhibition leaflet as “The time spent here by each of you will

be a stitch in the piece of musical embroidery by GREYCODE and jiiiiin,” the

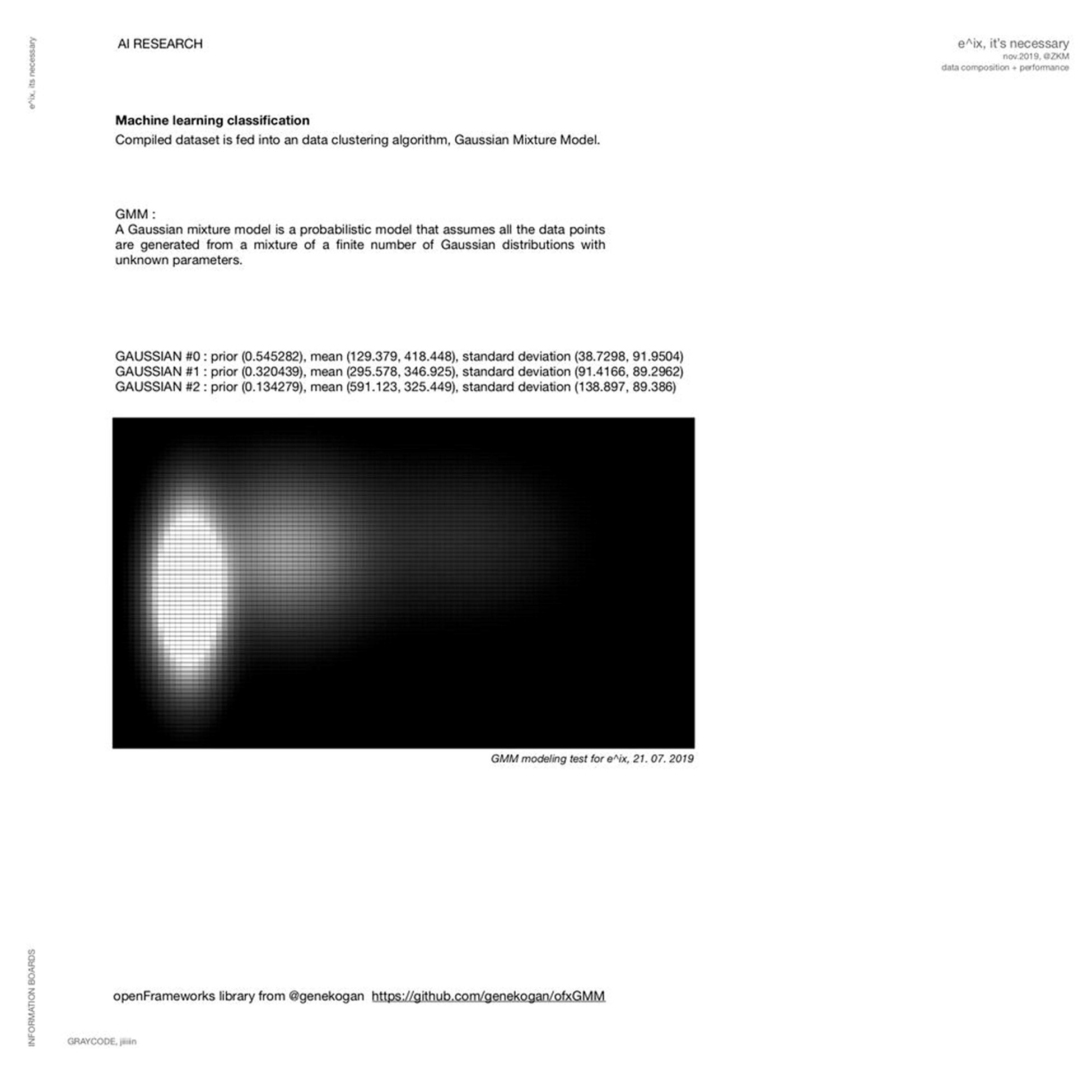

process of completing the exhibition is extremely mathematical. Accessing the

website (dc.seoul.kr) given by the docent at the exhibition allows the website

to quantify your IP address as well as how much time you spent in which

section. Ultimately, the data collected during the course of the exhibition is

used to fill the data deficit of “Data Composition -1” in order to ultimately

complete Data Composition.

Is this a form of “participation art?”

Absolutely not. In this exhibition, viewers do not participate in the artwork semantically. In information theory, what matters is not the semantics

of data or information; no matter what

you decide on―whether to receive a medical check-up, whom to marry,

or which smartphone model to buy―everything is converted into a certain

quantity of information. Here, the important matter is not the meaning or value

that you derive from the information, but the reduction of probability or

possibility that can be numerically calculated. While participation art

provides viewers with the experience of engaging in artwork and attribute the

creation of artwork not to a single individual but collectively to numerous

viewers, Data Composition does not incorporate viewers’

feelings and experiences of the exhibition as data required for the

completion of the exhibition.

What meaning does it hold then to create art using

only the data generated and collected from the time spent by viewers to access

the website? Answering this question calls for contemplation on the status of

data and information in today’s world. Searching for information on web search

engines, purchasing goods on online malls, and ordering food on online

platforms using a credit card have naturally become a part of our daily lives,

as well as “liking” or “sharing” posts or leaving comments on Facebook,

Twitter, or Instagram, scanning QR codes with smartphones to check-in somewhere,

visiting gourmet restaurants based on web search results,

subscribing to Netflix or YouTube channels, and watching YouTube videos

on autoplay mode.

Indeed, we are connected to various networks for nearly half

of the 24 hours in a day. Every little thing

that we do online while we are connected to a

network, whether we recognize it or not, constantly generates data. Devices

such as smartwatches even record our physical activities such as daily steps

and sleeping hours as well as physiological indicators such as blood pressure

or heart rates and turn them into data. We are aware that this collection of

data is “changing the meaning of

labor, boundaries, and social structures at this very moment and

creating its own reality.” This excerpt from the artists’ notes for Data

Composition is by no means an exaggeration. Derived from our daily

lives and activities, this data becomes the basis for governments to promote

their policies, political parties to customize their campaigns according to the

characteristics of each voter group, and companies to develop their marketing

strategies and release advertisements tailored for

consumption trends.

Luciano Floridi pointed out that today’s

world has turned into an “infosphere,1” where we consider the

space of information to be synonymous with reality. The world we live in is

composed of data produced from our lives and activities, and the feedback loop

where such data is conversely used to regulate our lives and activities. Converting

visits to an art exhibition into data and feeding them back as a sound piece

does not represent a particularly significant act in itself to us, as we

already live in the infosphere. Rather, 《Data Composition》 is merely modelling our present situation itself in the form of an

exhibition.

Modelling instead of representation

At this point, the distinctive aspect of GRAYCODE and jiiiiin’s creative method becomes apparent; to these

artists, art is not representation. Through their exhibition, they model a

certain process with which we are associated

but nonetheless are not able to detect While

《Time in Ignorance》 presented the 720-hour compressed version of the process of

the transition towards the thermodynamic equilibrium that is constantly happening in the physical world

yet out of our perception, Data Composition focuses on the

process through which the time that

we live in is converted into data and fed back to us. What is the definitive

nature of this form of art? The concept of “representation,” which has long

defined art, is premised on a firm boundary that separates art from the actual

world. The idea that what we find in artwork is not the reality but its copy or representation has historically been the

fundamental condition for the creation and appreciation of art.

Contemporary

art has made various attempts to escape from this frame of representation, such

as happenings that actively create or stimulate an event instead of merely representing it, and durational art that demonstrates

the actual time in which the event occurs rather than representing it in a

compressed form. Nonetheless, not even happenings or durational art can

capture an event or process at a scale that far exceeds the human lifespan,

such as the birth of the universe through the Big Bang about 14 billion years

ago or the dissipation of the

order of energy in the physical world―events that transcend the scope of human experience and thereby dubbed

the “absolute reality” by Quentin Meillassoux. We demonstrate these events

using representations such as symbols or artificial signs. For example, science documentaries

represent the Big Bang, neurons exchanging electrical signals, or the curvature

of space-time in the universe through computer graphics. Strictly speaking,

however, what they convey is not the actual process

i t self but

merely i t s “virtual representation.”

No stranger to computers and programming,

GRAYCODE and jiiiiin refrain from using digital devices for the mere “virtual representation” of an event. Upon

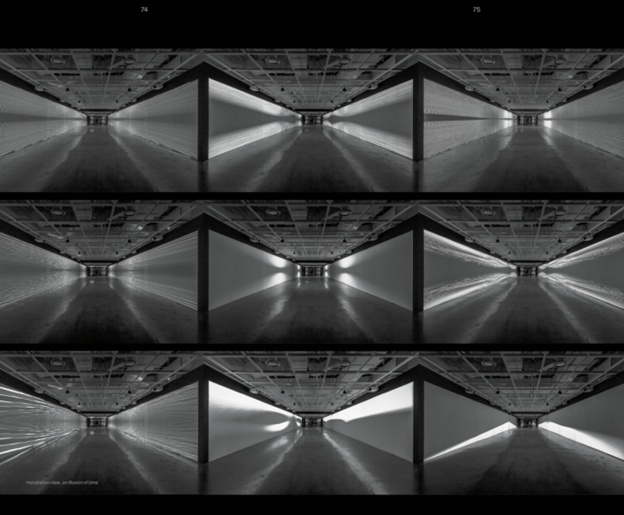

entering through the curtains at the entrance

of on illusion of time, one is surrounded

by the massive bundle of light rays generated by eight DLP projectors

within a space 2.4 meters high and 16 meters wide. Three speakers each

installed on both the left and right sides of the space emit sounds at two different frequencies, 39.4 and 61.0 Hz, which means

that the signal from the left is repeated 39.4 times a second, while the signal

from the right repeats 61 times per second. At the spot where the visitor

stands, these different frequencies clash against each other and modulate

through mutual interference. The Moiré patterns projected on the walls on both

sides are also the product of the interference between the lights emanating

from each side. Here, what the viewers see and hear is not the symbolic or virtual representation of

the interference between lights and

sounds, but the actual phenomenon of interference occurring at that very

moment. As the body of the viewer moves in the midst of the interference, the

sounds and lights undergo subtle changes.

It is incorrect to describe on illusion

of time as an “interactive” artwork, simply because movements of the

viewers can cause change in the piece. Interactive works generally utilize

movement sensors and audiovisual elements that change with much clearer causation by such movements, aiming to

directly intrigue the viewers. In contrast,

on illusion of time does not use any sensor that confirms to

the viewers that their movements are contributing to changes in the work,

because its intent is not to convey a certain audiovisual effect generated

through the viewers’ movements. Interactive media works that capture movements

using sensors and change accordingly tend to incur a certain loss, and on

illusion of time focuses on this loss. For example, the sound of

someone sweeping snow outside my window passes through the media of the window

glass and air to resonate with my eardrums and interferes with the sound of my

fingers typing on the keyboard. This event is not expressed in a concrete and perceivable form since there is no sensor or amplifier, but it is clearly

happening in the actual physical time and space around us. The fact that the

presence of viewers affects the sound interference in the space of On

Illusion of Time is subtly perceptible only by the modulation caused

when viewers speak. This is not the virtual representation of the sound or

light interference, but proof that the field of such interference is being

created.

Time

Of all the events that are hard for us to

detect but are nonetheless constantly happening, could anything be subtler and

more difficult to capture than time itself? The artists have been interested in

time as the theme of their works since their

first exhibition, 《Time in Ignorance 》. In their latest

exhibition, time is once again the core subject of their work. In the title of the piece, on illusion

of time, and the

Einstein quote written on the wall at the exhibition venue, which reads “People

like us who believe in physics know that the distinction between past, present

and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion,” the word “time” appears

alongside the word “illusion.” The Einstein quote is criticizing Newton’s

notion of “absolute time” that still rules over the general concept of time

today. To Einstein, who theorized

that time can bend or expand depending on the existence of matter in the

universe and changes in such matter, and that the disappearance of matter would

also mean the disappearance of time, the Newtonian concept of absolute

time―time that flows equably and at the same speed in every part in the

universe, regardless of matter or material changes, and follows the clear

causal order between the before and the after, and the past and the future2―represents nothing but

an “illusion.”

In 《Data Composition》, however, the word “illusion” is not only juxtaposed against Newton’s

concept of time. Einstein also remarked on time: “When you sit with a nice girl

for two hours, you think it's only a minute. But when you sit on a hot stove

for a minute, you think it's two hours. That's

relativity.3”

Through this remark, Einstein seems to claim that time is similar to a

subjective feeling towards each situation. Is it valid to understand time in

this way, even if the concept of absolute time is an illusion? The answer might

be found in Kant, whose works were enjoyed by Einstein. In Critique of

Pure Reason, Kant provided a truly intricate answer to the question:

Is time objective or subjective? According to Kant, time is an a priori form of

inner sense. Time is like a filter that one must penetrate

through to experience, a pair of a priori

sunglasses only through which one can see and experience the world. In the sense that one cannot experience anything

at all without passing through time, time is the absolute condition of our

every experience. This does not mean, however, that time “objectively” exists

beyond our experience. The point is that, though we cannot experience time

itself, our every experience occurs within (the a priori form of) time. Despite

the differences between their views on time4,

Kant and Einstein both certainly considered time as not independent from

objects and matter or our experience5 of them.

When we say we “experience time,” we do not

actually experience time itself, but changes in things such as the moving hands

of a clock, changing display of numbers on a digital clock, or growing

fingernails or hair. Still, we perceive time

as an inner sensation created as we imbue a sense of continuity to the changes

or movements of things we experience. To stretch this notion, we could even call it an “illusion.”

GRAYCODE and jiiiiin’s now slice demonstrates this aspect of time. In the piece, a display with a

diameter of over a meter shows luminescent particles seemingly floating in a

disorderly array in space or the deep sea. The video image is presented at the

speed of one frame per second in a disjointed way, like video footages sent

from a Mars rover back to Earth. Watching such videos, we think that each frame

that we are watching “now” is a “slice” cut from the continuity of time,

presuming that a certain change or movement is continuing to happen “between” each frame and the

next, though we cannot actually see it.

In this manner, the continuity

that we attach to the invisible gaps “between”

the changes of matter and objects creates an inner sensation that we consider

to be time. Strictly speaking, we cannot perceive the change or movement in

matter and objects within the frame of such continuity. When we glance at a bonfire once every five minutes, the

fire that we are seeing now is different from the fire that we will see after

five minutes has passed. Whether the flame

has become bigger

or smaller, we assign

continuity to what occurred “between” those changes and say that “time has

passed.” What if, instead, we continue

to look at the bonfire

without looking away? We may be able to trace changes that can be perceived, but we cannot capture all of

the microscopic changes that happen in the blink of an eye or during the

oxidation of matter. What we see, instead, is the series of discontinuous

images that represent the changes

of the bonfire. Time is what

we construct to make such images appear to be continuous6.

Data as anti-entropy

The exhibition presents another saying

related to time: “Time was, is, and will be.” It is quite different from the

Einstein quote in its context. When it is already understood that time is an

illusion, what does it mean to say that time was, is, and will be? Does it

indicate that, like those who believe the earth is flat, the illusion of

absolute time exists now, existed before, and will continue to exist?

Personally, it seems that this saying is related to the concept of entropy, on

which the artists’ previous exhibition was centered. Since the birth of the

universe, the only direction―if there is any―that has led the system

of the universe is the constant increase

of entropy.

The unequal

distribution of thermal

energy caused by the creation

of the universe as an orderly system inevitably pushes the world towards

thermodynamic equilibrium, as with hot water left at room temperature becoming cold

without additional heat and ice cubes dissolving in water. In What is

Life, Schrödinger explains this phenomenon as follows:

When a system that is not alive is isolated

or placed in a uniform environment, all motion usually comes to a standstill

very soon as a result of various kinds of friction; differences of electric or

chemical potential are equalized, substances which tend to form a chemical

compound do so, temperature becomes uniform by heat

conduction. After that, the whole system fades away into a dead, inert lump of

matter. A permanent

state is reached, in which

no observable events occur. The p h y s i c i s t c a l l s t h i s t h e s t a t e o f thermodynamic equilibrium, or of "maximum entropy.7”

Unlike ordinary matter,

however, living organisms can, despite existing within the process of reaching

maximum entropy, “maintain itself on a

stationary and fairly low entropy level,” according to Schrödinger. How can

living organisms, which are ultimately composed of matter, maintain their life

(order) against the natural law of entropy that continues to expand and dominates the entire material world? Schrödinger discover the answer in genetic

materials that enable living organisms to sustain themselves with enough

strength to “evade the tendency to disorder.8” Information theorist Floridi describes this notion as

follows:

Biological life is a constant struggle

against thermodynamic entropy. A living system

is any anti-entropic

informational entity, i.e., an informational object capable of instantiating procedural interactions (it embodies

information-processing operations) in order to maintain its existence

and/or reproduce itself (metabolism)9.

Every form of life, including human beings,

is an anti-entropic informational agent in that it extracts and

responds to information

from the environment in order to survive. What we do to sustain

life―eating, sleeping, avoiding being hurt,

striving to be healthy, obtaining information needed for our survival and life

from the environment, and responding properly to such information, or in other words, the entirety of our life itself―is a constant struggle

against the increase of entropy.

In this regard, today’s information society,

where all of our actions and physiological signs are converted into data,

embodies a kind of duality; it entails the possibility

for a dystopian future where everything in our life is tightly

controlled under information networks, while it is simultaneously resisting the

increase of entropy by “organizing” our actions and lives as information that

might otherwise have simply

become lost to thermodynamic equilibrium. Information technology such as big data or artificial

intelligence might be able to convert carbon emissions and plastic waste

that are recklessly discharged by human beings into systemized information. For

example, the international carbon

credit system, which was devised to reduce

greenhouse gas emissions across the world,

is based on data technology that can measure and calculate the amount of CO2

discharged by each country. Could it be that the trend

of converting human life into data presents at least a minute clue for a world

that is currently facing an ecological crisis?

1 Luciano Floridi, Information: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford

University Press, 2010.

2 “Absolute, true, and mathematical time, of itself, and

from its own nature, flows equably without relation to anything external, and

by another name is called duration: relative, apparent, and common time, is some sensible

and external (whether

accurate or unequable) measure of duration

by the means of motion,

which is commonly

used instead of true time; such as an hour, a day, a month, a year,”

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/newton-stm/scholium.html.

3 https://www.br.de/fernsehen/ard-alpha/programmkalender/sendung-1315134.html.

4 According to Einstein, time disappears along with matter;

Kant sees time as in its a priori form that exists without matter

that can be experienced. See https://www.menscheinstein.de/biografie/ biografie_jsp/key=2414.html.

5 The

space of matter in the universe,

as explained by Einstein, is not something we can experience

in person.

6 On the aforementioned perception and construction of time, see Römer, Inga & Bernet,

Rudolf & Taminiaux, J. & IJsseling, S. & Leonardy, H. & Lories,

D. & Melle,

Ullrich & Bernasconi, R. & Carr, D. & Casey, E.S. & Cobb-Stevens, R. & Courtine,

J.F. & Dastur,

F. & Düsing,

K. & Hart, J. & Held, K. & Kaehler,

K.E. & Lohmar,

D. & McKenna,

W.R. & Waldenfels, B. (2010). Husserl

– Zeitbewusstsein und

Zeitkonstitution. 10.1007/978-90-481-8590-0_2.

7 Schrödinger, What is Life?, Cambridge University Press, 1944, p70.

8 chrödinger, What is Life?, Cambridge University Press, 1944, p70.

9 Luciano Floridi, Information: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford

University Press, 2010.