We

often find ourselves wanting to visit a brand’s showroom—especially a flagship

store—instead of shopping online (even when the internet price might be

slightly cheaper) or going to a department store just to buy a certain outfit.

Likewise, there are times we want to visit a café whose coffee isn’t

particularly good but whose spatial design or ambience is stylish. Such

impulses are less about acquiring a type of clothing or a cup’s worth of

caffeine than about consuming an atmosphere that can only be felt by being

there. It’s an activity geared less toward practical purpose than toward

switching one’s mood.

Neologisms

popular among young office workers these days—“sibal-costs” (shi-bal-biyong)¹

or “squander-fun” (tang-jin-jaem)²—are connected to these “mood-lifting

activities.” The category spans everything from long overseas trips to a

few-second moments staring at cute animal GIFs or luscious dessert photos on

one’s timeline.

Though

it varies by person, the common denominator of “mood-lifting activities” can be

summarized as the consumption of something “cute,” “pretty,” or “sweet.” Like a

healing potion in an RPG, they function as the quickest, easiest tools for

shifting one’s vibe or mood. What’s interesting is that most of these

activities are coupled with photography. As the “cute / pretty / sweet” thing

passes through the camera, much of the object’s material / real qualities

evaporate. The object remains as an image that not only is modified by “cute /

pretty / sweet” but comes to represent “cuteness / prettiness / sweetness”

itself. Scattered across social-media timelines, such images are consumed as

images per se. In that light, we can’t dismiss people who diligently take

photos in cafés as mere selfie- or SNS-addicts. Perhaps they are those who most

actively enjoy the “ambience” they want.

In

this way, browsing a carefully designed offline store—without buying the

clothes—can be more effective for lifting one’s mood than ordering garments

online to be delivered. If we think along these lines, when indulging a feeling

or enjoying a particular atmosphere, the process of purchasing or eating some

physical thing may not be that important. From this perspective, there are

cases on the timeline in which the number of people who see something only as a

photo far exceeds those who have actually owned or eaten it. Like a “rice cake

in a painting,” Serious Hunger—a dessert brand that exists only in photos and

videos on timelines—falls squarely into this case. Occasionally someone appears

claiming to have tasted it, but no one knows where to go to buy it. The brand

“Serious Hunger” and its SNS accounts are visible, but there is no physical

shop that sells desserts. As a result, many wonder whether it really exists,

and if so, how they might try it. Others, regardless of whether it can be

eaten, simply focus on the ecstasy of looking at the images that Serious Hunger

releases.

“Serious

Hunger” is one of the various SNS accounts run by artist Song Min Jung, who has

primarily presented video works; it is simultaneously a fictional dessert shop

and an artwork in a mixed form of video and installation. In that it offers a

mood through images rather than the taste of desserts themselves, it connects

to the “mood-lifting activities” mentioned above. Is it then a fictional

dessert shop? To be sure, it seems “virtual” in that it does not exist

physically and you cannot purchase cakes or cookies through its SNS accounts;

but it is also hard to say it resides purely in the realm of the virtual.

Desserts operate as auxiliary elements that create a certain mood, and anyone

can feel the mood proposed by the artist through this account.

Thus, although

“Serious Hunger” is a dessert brand within a world the artist has created, it

does not stay only in the virtual. It functions most effectively with one foot

in both reality and virtuality—through the SNS timeline.

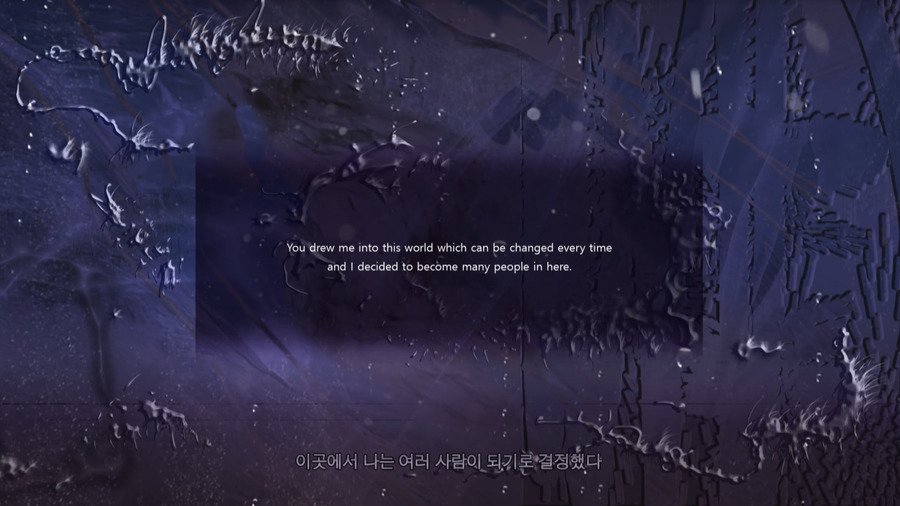

The

video works of “Serious Hunger,” which are often in the form of commercials,

state or imply through on-screen captions / narration that they will switch

your “mood”:

“It's

a joke or a fictional persona; there, we are not hungry at all. We just look

cool.”

— Serious Hunger x Zeewooman, 2016

“From

now on, we will transmit the mood we propose. We’ll suggest the most accurate

mood possible.”

— Double Deep Hot Sugar: the Romance of Story, 2016

“Intuitive

cream improves your mood immediately.”

— Cream Cream Orange, 2017

These

“mood-switching elements” stem less from the videos themselves than from the

dessert-table settings presented at exhibitions and events in which “Serious

Hunger” has participated, and from the images that document them. As noted,

whether visitors actually get to taste the cakes and desserts on the table is

not very important here. Where “Serious Hunger” truly functions as an artwork

is in asking how the atmosphere of that place is constructed, and what moods

and experiences viewers feel and consume within it.

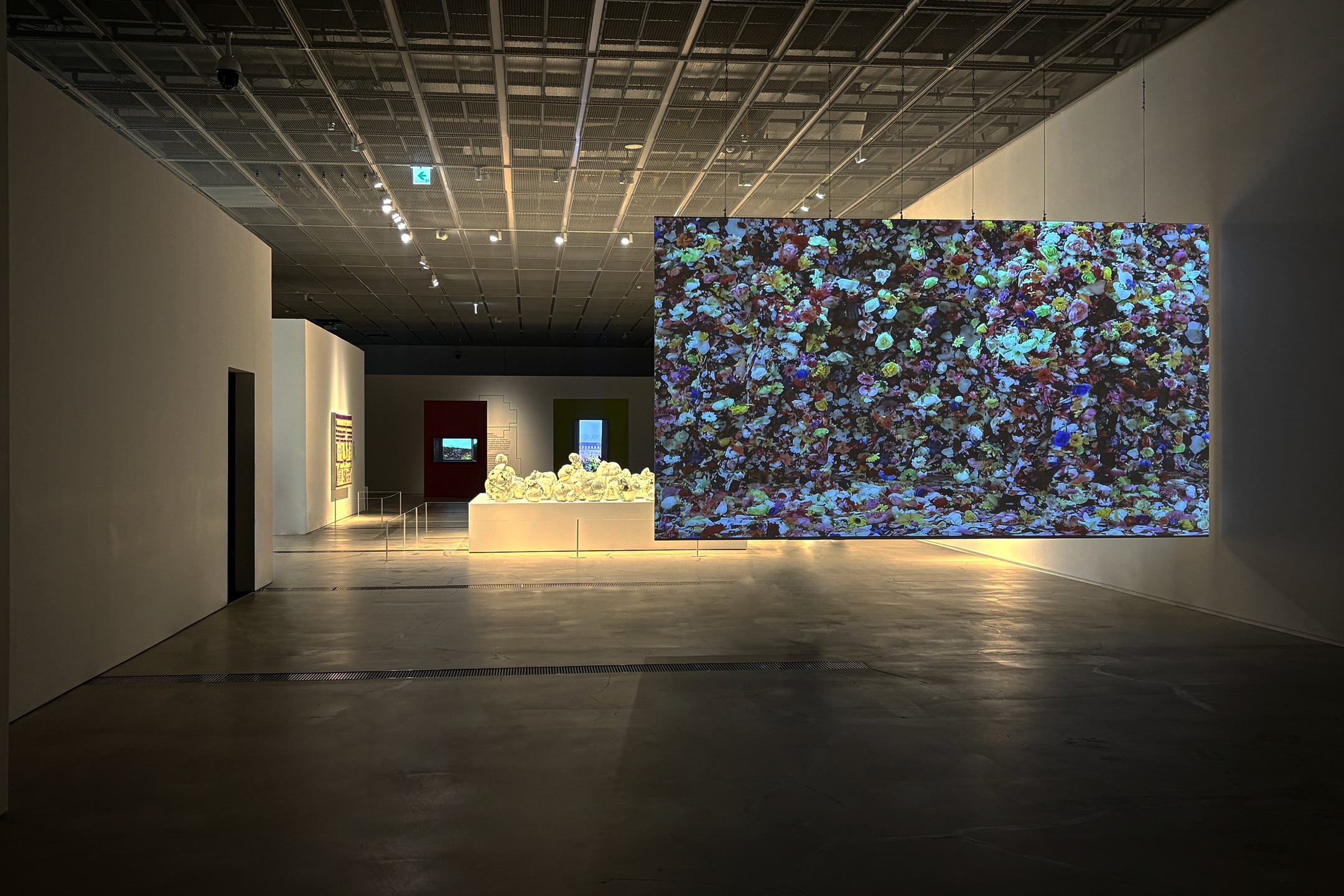

Recently,

“Serious Hunger” staged a “ceremony” for the opening of the second-floor

exhibition space at Tastehouse. Visitors finally faced a table on which cakes

they had seen on timelines were harmoniously arranged with flowers and plants

in collaboration with a plant shop; yet, again, they could not taste the cakes.

Instead, they could enjoy the atmosphere “Serious Hunger” proposed and examine

the elements on the table in their own ways while taking photographs. This

logic also held in earlier exhibitions and events such as 《Otaku Project》 (Buk-Seoul Museum of Art,

2017), 《Dessert Exhibition》

(COEX, 2017), and 《Artist’s Lunchbox》 (Seoul Museum of Art, 2017).

In October of that year, in 《Taste Pavilion》 (Tastehouse, 2017), Song Min

Jung also presented another account, “Jacqueline,” set as the proprietor of

“Est-ce vraiment nécessaire?” (“Is that really necessary?”), a café-cum-general

store in Juvisy, France. Accompanied by an instructional video, the “Jacqueline”

corner—staged as a small refrigerator—allowed only those who paid an “opening

fee” of 2,000 KRW to open the fridge and peruse and purchase items such as

cookies and chocolates. Here, the “opening fee” became the price paid to gain

the opportunity to experience and purchase the atmosphere created through

“Jacqueline.” This setup makes the artist’s intent in “Serious Hunger” or

“Jacqueline” crystal clear. It also leads participating viewers to recognize

more explicitly what it is they are consuming.

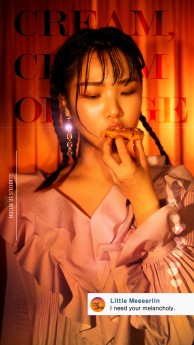

The

mood that “Serious Hunger” creates may seem dominated by a cute and pretty

vibe—like cakes and table settings. Yet, at the same time, something hollow can

be sensed; from a corner of the thoroughly staged image, a tinge of melancholy

and loneliness leaks out. Across the body of video works as well, “Serious

Hunger” does not merely evoke a mood of cuteness / prettiness / sweetness. The

act of consuming “cute / pretty / sweet” things³ as “mood-lifters” reflects

that much reality’s melancholy and stress, and the way “Serious Hunger”

“transmits an accurate mood / improves your mood immediately” likely operates

in a similar context.

Consider timelines in which a tweet about wanting to die

is followed by retweeted cat or dog photos: what Song Min Jung intends through

“Serious Hunger” is closer to showing the very mode by which (mostly cute)

photogenic things trend and are consumed in the SNS world. Thanks to this, what

viewers can consume / enjoy as an “artwork” in “Serious Hunger” is not confined

to the visibly presented cakes or video pieces. For the artist, the timeline,

like a canvas that bears a painterly image, becomes the support that sends out

Serious Hunger (as image) as a “virtual dessert shop.” In this sense, the

timeline’s reactions to the cake images function not as merely mistaken

audience feedback but as another axis constituting the work.

Song Min Jung

Working with “current states (current moods)” as material, the artist provides

a mood she has set or becomes a fictional account that links herself onto the

timeline. “Serious Hunger” is one such account constituting the work, a

fictional dessert brand that borrows the form of advertising to link to

viewers—or consumers.

¹

A portmanteau of the Korean profanity sibal and “cost,” meaning “an

expense that would not have occurred had one not been stressed.” For example,

splurging on a perm at an upscale salon in a fit of anger, or taking a taxi on

a route one normally travels by bus or subway. (Parkmungak, Dictionary of

Current Affairs, 2017)

² A neologism combining tangjin (to squander one’s wealth)

and jaem (fun), meaning the “fun of small squanderings.” As economic

recession and job shortages persist, younger generations with modest incomes

spend all available money to extract maximum satisfaction—an approach to stress

relief that indulges in small, unnecessary purchases.

(Parkmungak, Dictionary of Current Affairs, 2017)

³ This can include cute animals and babies; character goods; appetizing food;

sleek interior design; and even “photogenic artworks / exhibitions.”