Appearing

at the turn of the 20th century into the 21st century, the term “experience economy” refers to the structural

characteristics of an experience society wherein services that provide certain

experience supplanted industrial products as the major commodity in the market.

“Experiential turn” is the term

Dorothea von Hantelmann uses in reference to contemporary art styles that

resonate with such economic and cultural models of western society, suggesting

the 1960s as the origin.1 Key concepts of the main subjects of experience such as

spectators and situation led to the legacy of proactive art that resisted

against the mausoleum-like museum and modernism.

Also leaving behind such

legacy was the tendency to strive towards the immaterial, atypical, and

ephemeral nature of time, resulting in movements and genres such as Fluxus,

conceptual art, process art, feminism art, and performance art. In 《Work Ethic》 (2003), an exhibition held

at the Baltimore Museum Art, curator Helen Anne Molesworth addressed the shift

in the work of artists. Specifically, Molesworth categorized the roles of

artists since 1960s as workers, managers, and experience makers. She then added

one more category to this list — “the artist who does

not work” in face of the age of 24/7 wherein boundary

between labor and leisure have vanished.

This category was a conscious

recognition of the leading economic model of the era, implicitly arguing that

the aesthetic foundation of art has moved from art objects to experience, and

that such trend will only grow stronger. Molesworth referred to the art of the

1960s in order to visualize the aspects of such contemporary art. She believed

that the art scene of the time was comprised of dynamic and thriving practice.

Molesworth also considered such practice a valid way to pursue art, and that

the return of such practice was already in motion or being requested.2

However,

a rather challenging destiny awaits the once-progressive art as it comes in

contact with the experience economy model. Rosalind Krauss already saw through

the desires of the “late capitalism

museums” to accept minimalism and how minimalism

already had the corresponding production conditions prepared. The “cultural theory” which enabled this presents

us with the experience of the immersive present, synchronic time, and the

corporeally experienced visual field.3 This stands as a non-place of immersion devoid of fiction,

different from other distracted awareness. 20 long years have passed since

then. During that time, we passed through an era that conditioned us to

understand and accept the world based on certain “ambience, emotions, or mood.”

In fact, we

still trudge along with such principle, as if we have been hypnotized. We are

no longer necessarily curious about what incites such ambience, mood, and

feelings. Rather, we stubbornly advocate that the feelings and moods themselves

comprise the entirety of real existence. “It is easier

to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism,” while “the old battles between

appropriation and recovery, subversion and integration seem to be over now.”4 Meanwhile, fashion houses and art practice have become more

synonymous with each other than anything else.5 This is hardly surprising when considering how the emphasis

on experience has become so rampant in today’s world that attempting to criticize the fact that experience

overpowers the objective world is nearly frowned upon.

Such state of being

resonates with the world perspective wherein fragmented relativism of

individuals substitute the truth, as made evident by the term “post-truth.” The objects and images of the

post-truth world do not even consider what they are portraying, only striving

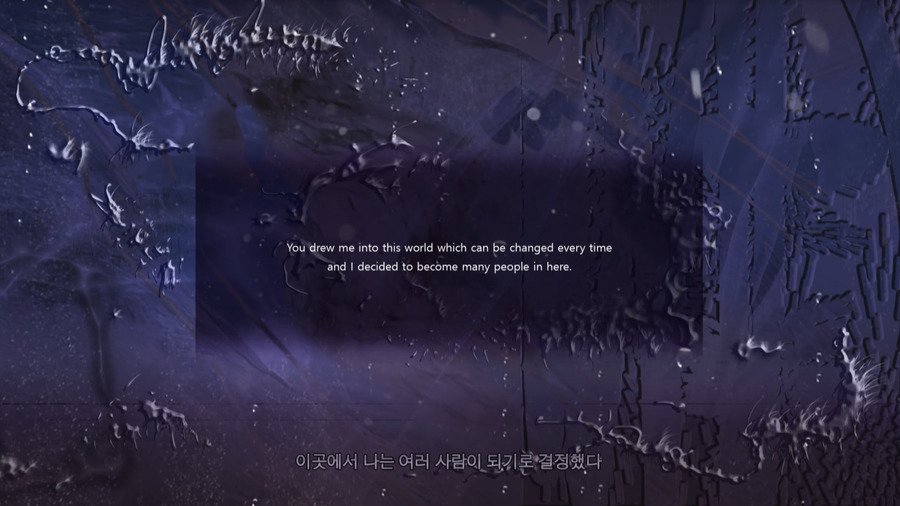

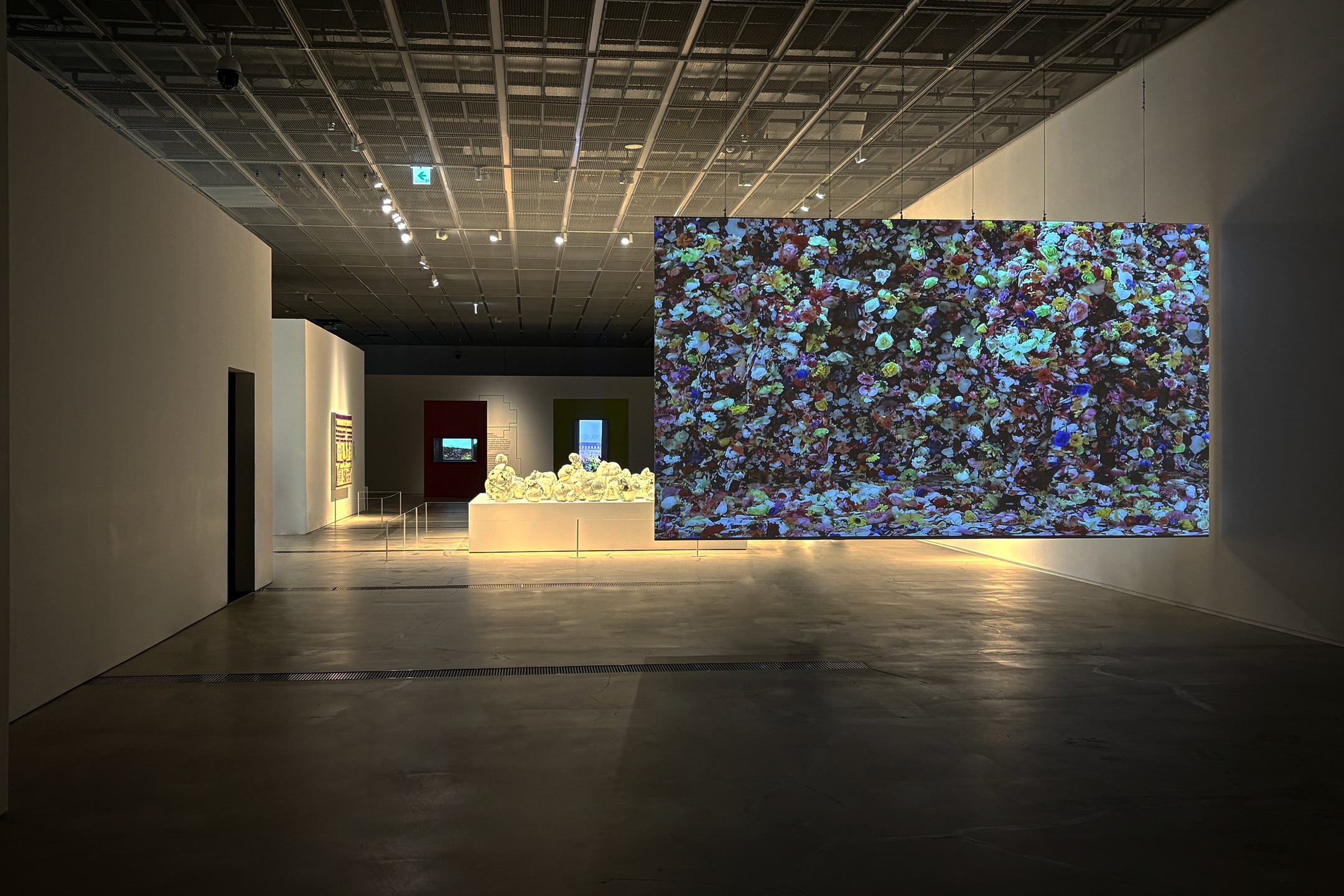

towards forming some kind of experience. This is the premise on which Song Min

Jung’s works lie and operate. Song’s screens do not show anything specific, but rather only provides a

certain experience. The screen serves as a variable that does not bear its own

value, and a mediator which reconstructs reality.

In

the summer of 2018, I had the opportunity to binge watch most of Song’s videos at the Touchscreen, a video exhibition program hosted at

ONEROOM. This experience in the exhibition space situated in Euljiro, Seoul,

was a rather startling one. If screening is a device for immersion and

appreciation of the moving images projected before our eyes, our relationship

with the images are mostly defined by the inert tendency to see, read, and

understand the images within the frame.

However, the reason I was puzzled

throughout the duration of that relationship stems from the fact that I could

never figure out what was meant to be shown in several of Song’s shorter works borrowing the grammar of advertisement footage such

as Est-ce vraiment nécessaire? (2017), NEW!

Fluffy Rukuru (2017), Cream, Cream Orange (2017).

To be precise, these videos are missing the object that is meant to be shown in

the first place. Instead, they merely provide clues for the speculative

existence through audiovisual effects. The expression “speculative

existence” here refers not to specific products or

brands, but rather the category of products reminded by a certain ambience and

the collection of terms that have familial similarities.

As Est-ce

vraiment nécessaire? displays the green typeface image along

with the cheerful background music, it emphasizes the typical nature of French

narration and therefore encourages the viewer to imagine the list of items that

would be sold at a typical ‘café.’ Likewise, Cream, Cream Orange presents

dreamy sounds with an alluring array of objects with smooth, shiny texture, as

the confident, enunciated narration in English reminds the viewer of beauty

products.

Come

to think of it, there must have been a reason why I felt like I was at the

wrong place when I saw the screening. This is because Song’s videos were created to be briefly glanced at in the context of the

virtual timeline of online videos or specific, artificially furnished spaces;

the most appropriate devices for screening such footage would thus be personal

media devices like the smartphone instead of a projector. For example, the

music video of Pluto (lyrics and music by Shin Hae Gyeong) produced

by Song features the user interface of a smartphone. The footage looks like it

has been captured from the smartphone screen when it is played on the computer,

but when played on a smartphone, the video is optimized to appear as if the

photo app is running on the phone in real-time or the phone is actually

receiving an incoming call.

As such, the music video temporarily functions as

the user’s screen itself instead of a media content

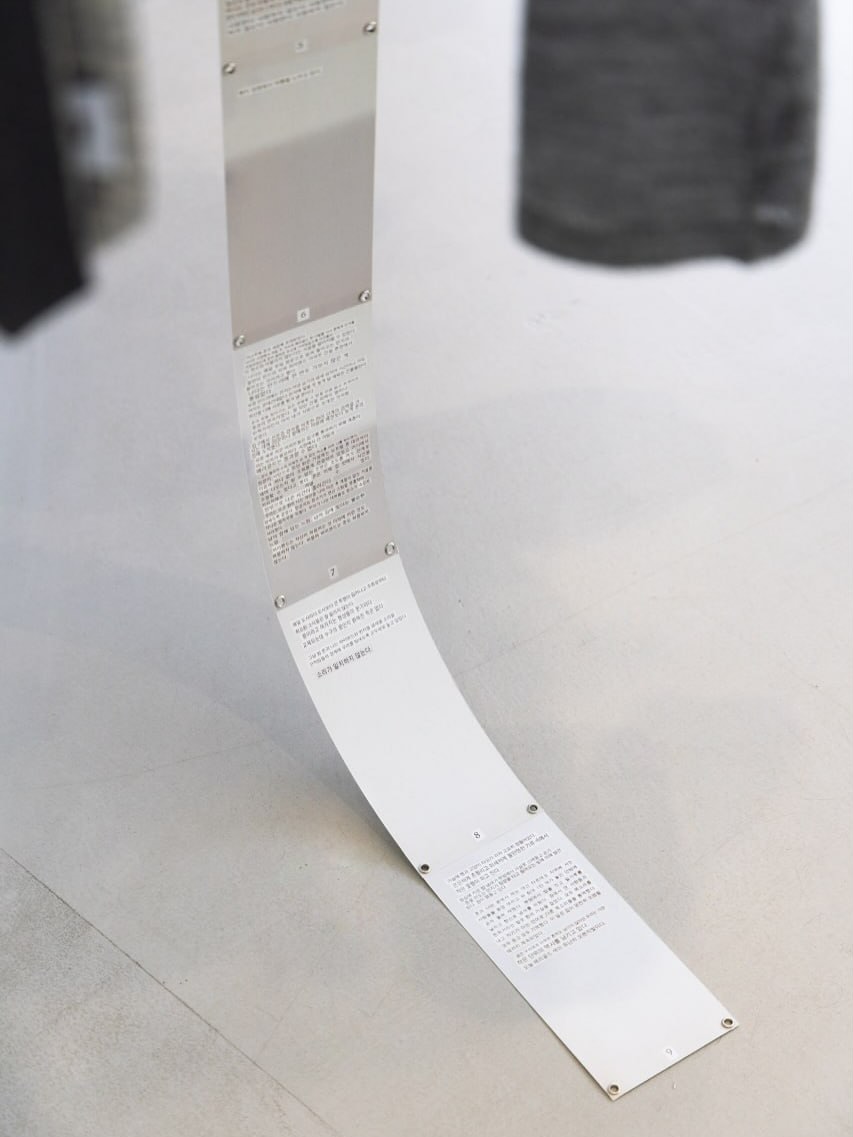

played on the device. In her solo exhibition 《COLD MOOD(1000% soft point)》 (2018, Tastehouse), Song loaded her promotion video to be viewed on

a tablet device as the viewer roamed around the environment staged across the

exhibition space. The screen held in the moving user’s hands controls the user’s behavior and

introduces immersion into the space. The implications of the screen’s interface and the power thereof are most appropriately visualized

in the performance piece Caroline, Drift Train, which

presents the exhibition space as a train station in Caroline facing delayed arrivals

due to heavy snow. The dashboards projected onto the screen display the delayed

train schedule, while the Christmas tree lights blink.

Peaceful classical music

plays throughout the hall while a narration in a foreign language reminds one

of any standard train station’s announcements. While

these elements allude to a specific situation, the messages sent to the

smartphone invite the spectators to become immersed in a virtual world. As the

physical body steps into the exhibition space groomed to provide the ambience

of some foreign train station, it establishes another relationship with the

smartphone screen to fill in the time of reality. Personal media devices like

smartphones uses the spectacle of decision-experience that provides an endless

series of images and user interface to immerse the user into the screen-based

reality. The screen becomes the focal point where the desires of the members of

capitalism and experience society converge. Such focal point is teeming with

bodiless images, time stretched across timelines, space scattered throughout

databases, and “absolutely replaceable reality.” And this is also the realism of nationalistic ideology which lauds

things like the world’s first 5G commercial launch or

technological advancements in mobile devices.

Song

experiments with how the screens of personal media devices, one of the most

powerful objects of this era, can control and rearrange the experience and

behavior of users. Multiple accounts, fictional brands, narration in a foreign

language, the effect of images without the products, and mood as an experience

are the representation of the realism of fictional images that constitute

reality, wherein the power of objects themselves form the center of the very

ecosystem they inhabit. Such realism that Song represents repeatedly alludes to

the city of Seoul. In addition to becoming the mediator herself who weaves

together the screen-based experience and images that have material impact, Song

continuously produced essay videos from the perspectives of the observer and

contemplator. Such works track down the way the artist recognizes the

contemporary world or the visuality required to recognize the contemporary

world. In sum, Song’s true interest

lies neither in the binary classification of the virtual versus the real nor in

the entertainment that stems from such gaps. In fact, Song requests the

encounter of the world through the generation of narrative within that

construct.

I

cannot help but think, first and foremost, of (K)night(2015).

Here, Song deconstructs the world “(k)night” into a group of subcomponents: “k,” “night,” “knight,” and “( ).” She then

uses and combines them as semantic elements of a sentence atop the space of

book pages. For example, “k went into the ( ) at night.” The video shows one sentence being written on each page, which is

turned when the narrator reads the sentence, and so on. What caught my gaze was

the way Song placed the semantic elements of the sentence on the pages. The

words are scattered across the page with large gaps in between each other.

Although it is possible, to a degree, to connect the words in sequence using

certain rules of sentence formation, even such rules are not that stringent.

For example, there is a page containing the words “is,”

“wide,” and “small.”

The words are arranged with different latitudes and longitudes like

the three points of a triangle. The narrator then reads two sentences comprised

of the words: “blank is wide,”

and “blank is small.” This also

serves as a clue for understanding the scenes in works like the ‘DOUBLE

DEEP HOT SUGAR-the Romance of Story’ series, where multiple footage

frames, captured images, and emoticons float about. The individual elements in

the screen are independent from each other but also instantly create meaning

through random connections, implying the absence of direction. Unable to create

strong bonds, the elements easily break down and move on to the next meaning in

a fluid manner. In this context, Song’s videos most

often show images of water and liquid. Such images serve as a direct confession

of the gap between the beautiful visual experience (like the beautiful

sparkling surface of the Han River) and the unpleasant daily life that one must

bear through in Seoul (COLD MOOD (1000% soft point)). At the same time, the

water and liquid represent the transparency and opacity of the world, i.e. a

reference to resolution and virtual layers (Omnia Vincit Amor.Ang, 2015).

“Bullshit” is the term the philosopher Harry

G. Frankfurt used to refer to the utterance of a party who does not care for

the truth as long as they can achieve their certain goals. Bullshit in this

sense can be clearly distinguished from a lie, which at least recognizes the

truth. While the criticism on bullshit was derived from the populism of

right-wing politics, bullshit is actually deeply ingrained in contemporary

visual culture and system of thinking. The fervor over bullshit is quantified

into the number of YouTube views used to boast one’s

content, and visualized into the comments responding passionately to

provocative news articles. Bullshit grows more rampant in societies where

experience supplants the value of truth and thereby establishes its own

reality.

However, the problem lies in the fact that it can be extremely

difficult to expose the fallacy of bullshit. Mark Fisher said that actual

resistance against the fallacies of capitalism can “threaten

[capitalism] only when it can show the inconsistency and indefensibility of

capitalism, i.e. when it can show that there is no such thing as realism in the

ostensible ‘realism’ of

capitalism.”6 Then how could one go about exposing such fallacies? This is

the strategic question that must be explored amidst the legacy of the

avant-garde that stood helpless against capitalism. What is certain is that in

order to intervene with and arbitrate the governing system of certain eras, it

is vital to use the system and sentimentality of that era as the interface. If

we can expose certain gaps while putting such intervention into practice, we

can come face to face with the contradictions or emptiness lying under the

seemingly solid surface of that coincidental world. Then we will be able to put

Song’s thoughts and experimentations on the mobile

media-device screen into the aforementioned practice. Song asks us what this

world subjectifies us into, what it makes us see, how it makes us behave, and

how the world is formed and re-formed from there.

1. Dorothea von Hantelmann, “The Experiential Turn.” On Performativity, accessed April 9, 2019.

2. Helen Molesworth; essays by Darsie Alexander…(et al.), Work Ethic (The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003).

3. 로잘린드 크라우스, 후기자본주의 미술관의 문화적 논리, 모더니즘 이후 미술의 화두 2, 전시의 담론, 윤난지 편역(서울: 눈빛, 2002).

Rosalind Krauss, “The Cultural Logic of the Late Capitalist Museum,” (Art Topics Since Modernism 2: The Discourse of Exhibition, Noonbit, 2002.

4. 마크 피셔, 자본주의 리얼리즘: 대안은 없는가, 박진철 옮김(서울: 리시올, 2018), 11, 23쪽.

Mark Fisher, trans. Jin Cheol Park, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, Luciole, 2018, p.11, 23

5. 시각예술가 도미니크 곤살레스-포에스터, 건축가 마샬 비예이(일명 갈피온느), 조명 디자이너 브누아 라로로 구성된 포스트 9은 2000년부터 2012년까지 니콜라 게스키에르가 디렉터로 있던 발렌시아가의 전 세계의 매장을 디자인했다. 도미니크 곤살레스-포에스터는 다음과 같이 말한다. “당시 대부분의 매장이 화이트 큐브나 갤러리의 모습을 하고 있었고 나는 우리가 다른 방향으로 나아가야 한다고, 풍경을 만들고 몰입적인 공간을 만들어야 한다고 생각했다. … 그것은 대단한 경험이었다. 프랑스 가수 크리스토프와 알랭 바슝의 무대를 디자인했던 것, 비디오 작업을 했던 것, 또 칸 영화제에서 상영했던 단편 영화를 만드는 것과 비슷한 경험이었다. 갤러리와 미술관의 벽을 넘어 나가는 기분이었고, 그것은 당시 내가 원하던 것이었다.”

Comprised of the visual artist Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, architect Galfione, and light designer Benoit Lalloz, Poste 9 designed all the Balenciaga stores across the world from 2000 to 2012, when Nicolas Ghesquière served as director for the brand. Gonzalez-Foerster aid of the project, “Most of the stores at the time were shaped like white cubes or galleries, and I thought we must head towards another direction, to create landscapes and immersive space… That was an incredible experience. It was akin to designing the stage for the French singers Christophe and Alain Bahsung, videography work, and creating short films featured at the Cannes. It felt like we were going beyond the walls of the gallery and museum, which was what I wanted at the time.” Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster interviewed by Philip Pilekjær, “Landscapes for Balenciaga,” Provence Report, Autumm/Winter (2018/2019), p. 15.

6. 마크 피셔, 앞의 책, 37쪽.

Mark Fisher, Ibid., p.37.