The

first time we encountered the word “barrier-conscious” was in a research

project we participated in during 2018. It was a project titled “Research on

the Direction of Disability Culture and Arts Education and Development of

Teaching Materials,” carried out by the creative group Bigija with support from

the Korea Disability Arts and Culture Center, in which Kim Ji-young, Shin

Won-jung, Shin Jae, Yousun, Choi Sun-young, and Oh Hana participated. The

result came out as a small booklet titled Meeting Through

Expression Without Expectation (Note 1), but the word or concept

of “barrier-conscious” was not included in it. It was only a passing term in

the materials we used as reference, and it was not a commonly used word or

concept.

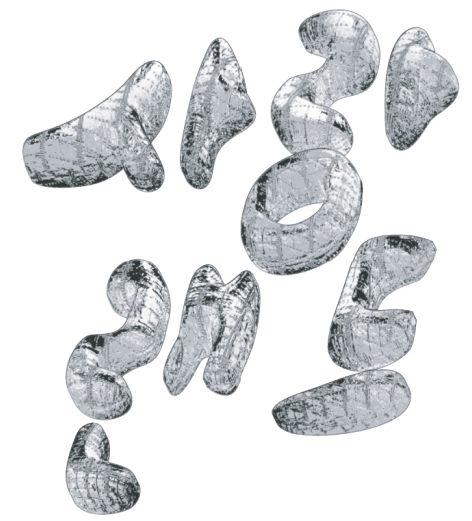

Takayuki

Mitsushima, who spoke of barrier-consciousness, is a totally blind person with

a visual disability, an acupuncturist, and an artist who continues to work

creatively. Since 1992 he has been making sculptures using clay, and since 1995

he has been producing what he calls “constructed paintings” using drafting line

tape and cutting sheets. His works, which employ rings, wood, pins, and other

materials, can be seen, touched, heard, and experienced. Since 2020, he has

been running a gallery and atelier called “Atelier Mitsushima.” He began to

think about “barrier” while preparing a solo exhibition at Sendai Mediatheque

in 2010. At the time, after attending a lecture by the aesthetician Hiroshi

Yoshioka, he told him that he felt resistance to the word “barrier-free.”

“(…) Was it 2010? That year, there was an exhibition at Sendai

Mediatheque, and when I said that I felt resistance to barrier-free, he said,

‘Then how about barrier-conscious?’ Now that I think of it, maybe it was around

that time that I opened my eyes to installation.” (Takayuki Mitsushima) (Note

2)

Yoshioka

also described the situation at the time in this way:

“What I suggested to Mitsushima back then was ‘barrier-consciousness.’ For

example, removing a threshold is called barrier-free, but even in places where

visible barriers are gone, barriers still exist. Rather than saying they do not

exist when they do, wouldn’t it be healthier to ‘be conscious of the barrier

and to acknowledge its presence together’?” (Hiroshi Yoshioka) (Note 3)

Mitsushima

later developed his thoughts on barrier-consciousness, and in the preface to a

solo exhibition, he said that what he meant by barrier-consciousness was “a

wall that is made conscious, and that can be enjoyed.”

“(…) Somehow, the shops I like never have Braille blocks at the

entrance. There are countless barriers: hard-to-find entrances, steep stairs,

places marked with signs like ‘Watch your head!’ The food is delicious, but

there are no Braille menus. But a space where all barriers are removed and

everything is neat is boring. Everywhere looks the same. If I could only go to

places that are barrier-free, life’s joys would be reduced to one-tenth. So I

squeeze myself into difficult places to enter. By involving the shop staff or

people around me in the effort to get in, change happens.” (Note 4)

We

liked the term “barrier-conscious.” But we were not impressed by the fact that

Yoshioka had come up with it spontaneously or that Mitsushima had developed it

on his own. What drew us was wanting to understand why Mitsushima used the word

and with what feelings—because we ourselves were so attracted to it. A stance

of being conscious of barriers sounded to us like a declaration to remain

conscious of all barriers in the world.

The

way we think about barrier-consciousness is probably quite different from

Mitsushima’s. What feels like huge barriers to us might not feel like barriers

at all to him. There are enormous differences between us in age, generation,

educational background, gender, sexual identity, nationality, and so on, and we

know it is somewhat naïve to believe that he would think the same as us just

because we use the same term. It is like the phrase on a poster we once made:

“we welcome all.” The scope of “all” that can be welcomed varies greatly for

each person. For one person, “all” might include wheelchair users but not

LGBTQ+. For another, people with developmental disabilities and L and G are

fine, but T is excluded. And yet another may never have once thought that their

words or actions could themselves be barriers to someone else.

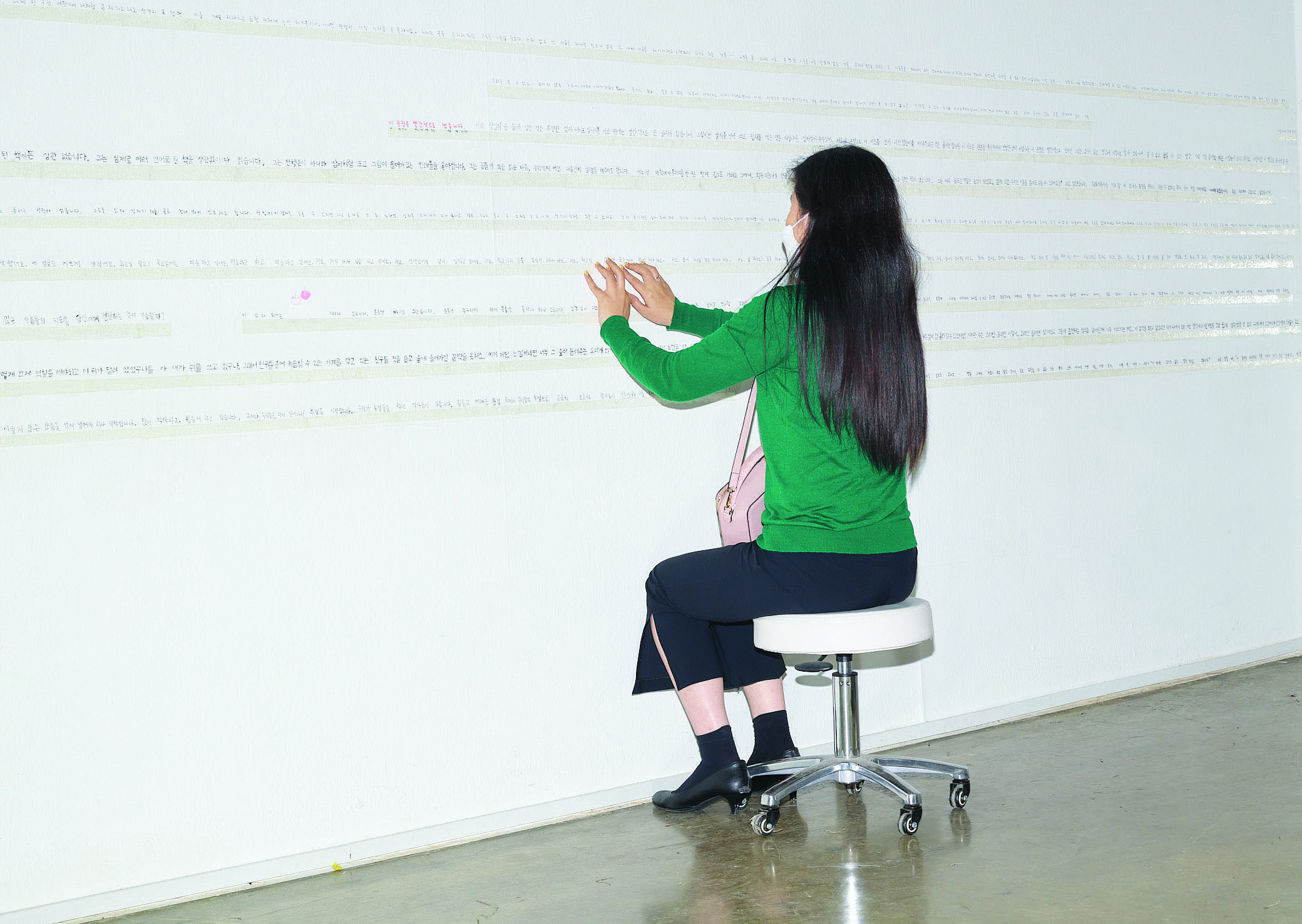

Mitsushima

wanted to create something that would cross barriers rather than eliminate

them. But for us, barriers are things that constantly pierce our bodies in

every moment. They are too large, too varied, too complex, and they form and

dissolve. A fleeting sneer, a contemptuous or desirous gaze, the looks we

receive when standing in the middle of a crosswalk during the morning commute

with wheelchair users, demanding the right to mobility and the right to live

outside institutions—these are just a few examples. The moment you point out

the problem of a physical barrier, thousands of invisible barriers appear.

Violence that comes from the fact that you and I are different. Violence that

many people, including ourselves, sometimes commit. Violence that many people

sometimes inflict upon themselves. How can we regain joy from the sensation of

being penetrated at once by hundreds of invisible barriers?

The

idea that barriers could be something to enjoy may be something only art can

express. It must be treated subtly and delicately. At least within the category

of art, it is absolutely not an expression that affirms a nondisabled-centered

society. We understand it as an expression that affirms differences between

individuals—differences that cannot and should not be eliminated. That is how

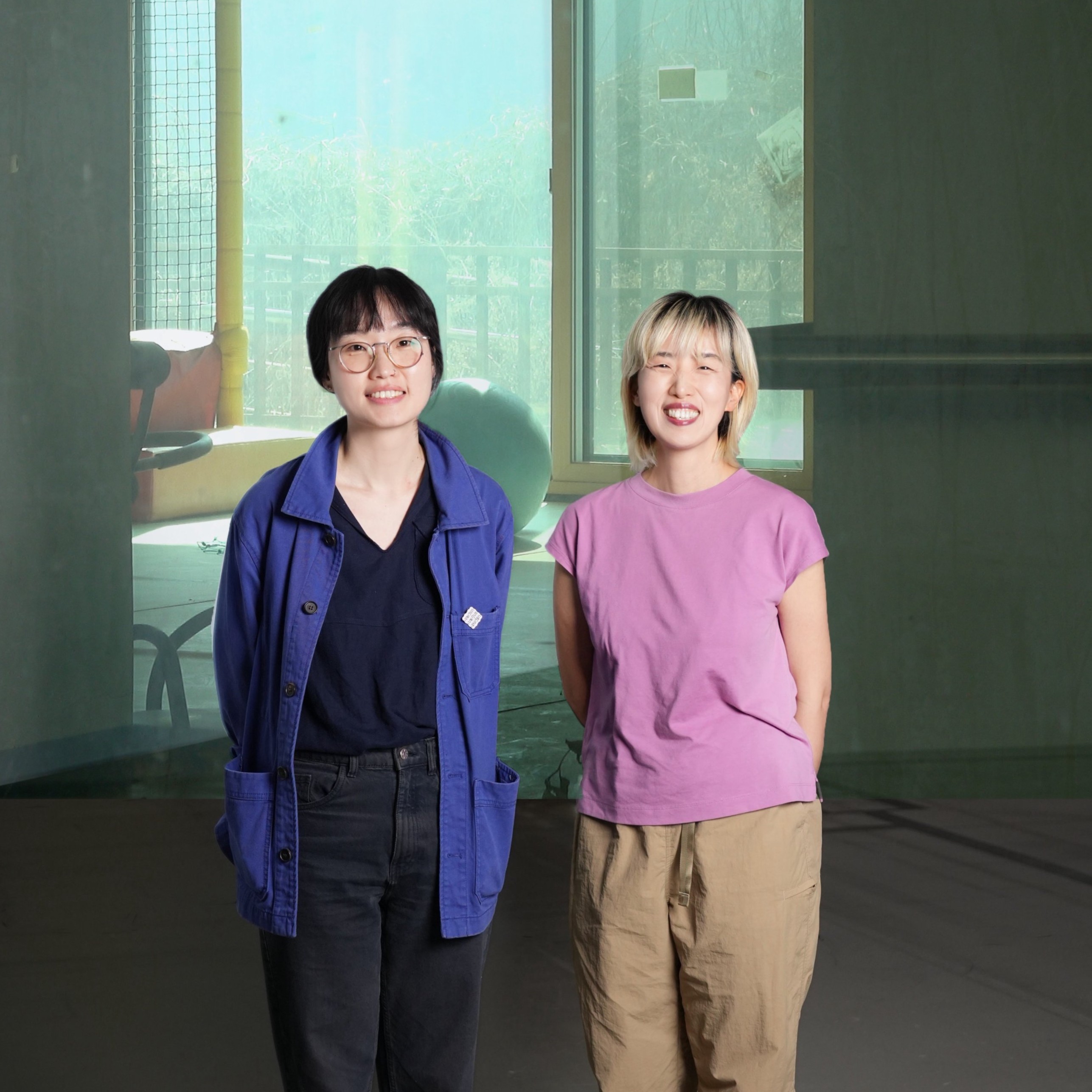

we interpret the works of dianalab and our friends, which have been explained

with the word “barrier-conscious.”

What

dianalab does may look like art brut, but it has never been art brut. It may

look like able art or outsider art, but it is not that either. It is not

barrier-free art. Although we use the word “barrier-conscious,” we are not the

same as the people who first spoke it. What we want is an art in which our

queer, disabled, women, animals, and those we have not yet thought of are all

both audience and artists expressing themselves. People say, “There is no such

thing. Just pick one. Make it simple. If it’s that complicated, it cannot be

realized in reality.” But as the poet Audre Lorde said, “There is no hierarchy

of oppression.” We have no intention of saying to one another, “Let us pause

our thoughts about other barriers for now, in order to eliminate a big

barrier.” And perhaps what was thought to be impossible, we have in fact

already been doing little by little for a long time.